by Manu Rodríguez

(translated from Spanish)

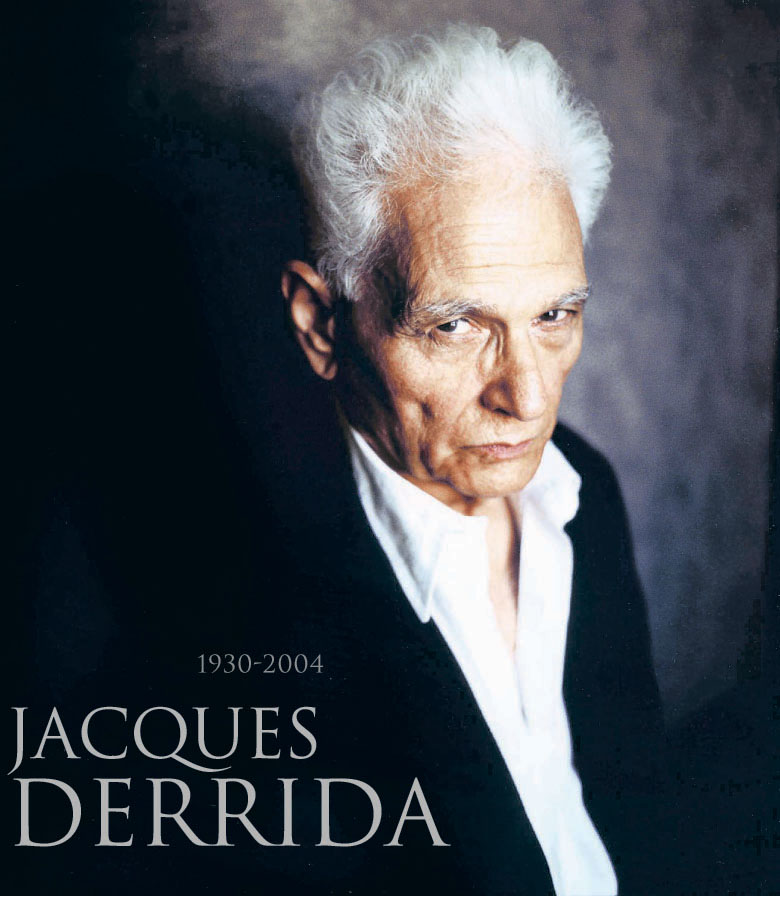

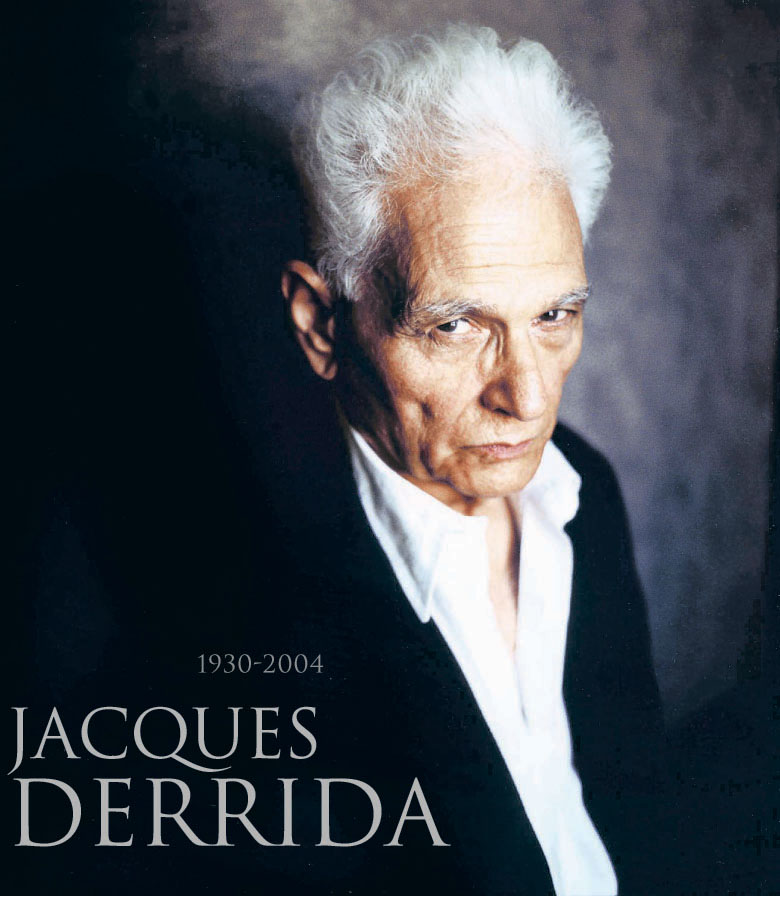

Derrida is, without doubt, the greatest Jewish thinker of late. I speak of what constitutes the whole Jewish “intelligentsia” of the past century. The “letters,” the “humanities”: Kafka, Freud, Lukacs, Benjamin, Arendt, Adorno, Marcuse, Levinas (the list is not exhaustive, of course). Derrida learned from all of them the best way of dealing with the Gentiles—learned from the mistakes of the Frankfurt School, for example. You had to use a different tone.

In view of the results of the present state of things, we can say with confidence that much of the scholarly work of the contemporary Jewish “intelligentsia” has been, and is, the destruction (“deconstruction,” if you prefer) of our culture. From all angles. They have introduced displeasure, mistrust, suspicion, discomfort throughout our culture in our painting, our music, our literature, our philosophy, our law, our traditions, all of our history since Marx… They poison the sources of our knowledge as harpies defile, desecrate, bumble, dirty, pollute our spiritual food.

It’s an old war that we do not want to register in our minds. A cold war. For more than two thousand years the Jews have declared war on the goyim, the gentile Europeans. Their first major victory was the Christianization of Europe, which was also our first step of Judaization (that massive process of forced and violent acculturation and enculturation of European populations 1700 years ago, which is extended, albeit more weakly, to this day). In the last two hundred years it seemed outclassed, left behind. But with Marx a new phase in this long war opened, which reached Derrida. Derrida is one of the last heirs of that pathway, a pathway opened by Marx: the destruction of the old institutions—the family, the nation, the religion, the symbolic parameters of a people, the frame, the skeleton: all of what had us standing.

The current preaching is the same of the past. The same destruction of our institutions and concepts. The same criticism of the nation, the homeland, the feeling of belonging to a land and a people, to our home, to our being ancestral and indigenous. And the same rising to the stars and the “selling” of all things Jewish. Jewish writing, Jewish culture… Theirs—Jewish identity—is untouchable. The Jew simply cannot be “deconstructed,” dismantled, censured, denied. The Jew is always affectionately embraced, and seductively presented as desirable, even as tempting. They tempt us, seduce us, divert us from our path. With one hand he destroys our identity and with the other he offers his. Illusionists, magicians, masters of distraction that swindle what is ours and attach to us what is foreign.

All this I say is shown to us in the media. It is the triumph of the rhetoric of advertising, of propaganda (Bernays). These are the times. Certain words, certain brands, certain slogans. Short messages, provocative, shocking, striking, bold, simple, catchy, leave a “footprint.” And also the gift, justice, forgiveness, friendship, hospitality. It is a “business” with “cause.”

A new Messianism comes now from the hand of Benjamin, Levinas, and Derrida (among many others, they are legion—and the converts) beyond the tart procedure of the Frankfurt School (those Maccabees). More subtle now, more Pauline, more cryptic, more cunning, more Marrano.

A new Messianism comes now from the hand of Benjamin, Levinas, and Derrida (among many others, they are legion—and the converts) beyond the tart procedure of the Frankfurt School (those Maccabees). More subtle now, more Pauline, more cryptic, more cunning, more Marrano.

Internationalism is preached to us; the lack of patriotism. It is a universal, political, transnational, cosmopolitan creed; it is a perspective of the stateless, the rootless. It promotes this narrative, this point of view, this being.

The humpback wants to make humpbacks of all of us. The stateless wants us all stateless. The wandering, the nomads. Not only landless, without culture as well. A thing is not without the other. One thing leads to another. We cannot be deprived of land without first being deprived of culture, of “sky”, of word, of light. First he rails against the super-symbolic structures, against that being symbolic in ours, against the traditions about ourselves, against the basis and foundations of our symbolic being, against our ancient identity, against our collective ancestral memory— we are nothing, indeed.

The Industrial Revolution will end the old ways Marx said; with the Ancient Regime, with the old institutions (European, Western). Why is that hope, that desire, and why the rush? The “world” in which we lived was declared old, sick, mad, guilty, bad, worthy of perishing. We are condemned to death.

We are declared sick (critical, destructive discourse) and they heal us (universalism, cosmopolitanism) alike. They bring both the disease and the remedy (in the manner of the old Jewish Messianism with its “original sin” and its restoring baptism).

But these “cures” or “remedies” are equally destructive. We are pushed toward the abyss (death and oblivion), we are blemished, denied, we are not left any outlet other than the “Other.”

We are being eliminated while we are offered the “diversity,” the Other, hospitality, cosmopolitanism, internationalism, the most suicidal altruism—indeed, the cure they say. We choose the Other, we place his interest before our own interests—the denial of oneself in short (“deny thyself”). And this evil, evil idea we like to accept as the highest and sublime “ideal.” Oh Miserable! It is the poisoned apple. The spreading among us of such universal principles seeks our destruction; that we voluntarily ignore ourselves, that we leave behind ours. Besides, our morality is reprehensible, punishable, it is the “bad” to remove.

Thus part of the cure is to destroy the attachment to the land, to the blood, to what is ours, all that should be up-rooted from the European goyim. Drive them away from their land, their people, away from our ends, away from ourselves. That was, and is, the way of salvation that we preach, and continues to be the cure. Now as then.

These are renewed attacks, and brutal, of the last two hundred years. From Marx to Derrida. New weapons, new missiles, new “reasoning,” new sophistry. Against everything that can strengthen and affirm. This is the whole strategy, and this is the role of the European Jewish “intelligentsia” to the Gentiles, that is what they have to do. They know that only by deconstructing us will they entirely succeed someday. And they spend their energy and greed toward that end. They dream but with the humiliation of the white European peoples. They want to see us defeated, vanquished, isolated, needy, few, solos. Oh, old Shylock!

They were not the first in this “path of destruction,” they were preceded by the enlightened after the Renaissance. The writings of the Enlightenment of the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries provided political, legal, economic, philosophical arguments of “progress.” But it is not the same fight to combat ideologically the Ancient Regime than trying to destroy the entire European culture.

Nietzsche also, unfortunately, provided plenty of material. And Heidegger. However, the same criticism that a European makes of his culture sounds different when performed by a Jew. Keep in mind who is the subject of an enunciation: who speaks here, who says that. While in a Jew’s mouth these reviews sound like the speech of an enemy, in a European mouth those words sound like those of a father or a mother, or a son, or a brother. Rebukes, corrects, encourages… The European seeks the good of his health; wants to make it better, stronger, more confident; wants to establish it on new foundations and purest symbolism. Nietzsche’s intention is that the European be exceeded, that he leaves behind all the ideological and spiritual, Platonic and Judeo-messianic period. A symbolic change, a change of “heaven,” a complete regeneration, a new dawn, a return perhaps. Marx (Jewish strategy) seeks the destruction of our worlds; Nietzsche seeks correction, transformation, renewal.

In any case, what is allowed to Nietzsche (one of us), is not to any stranger, whether Jewish, Christian, Muslim, or Chinese. Let them stick to their “stuff.”

Why do we allow these strangers interfere in our affairs? Our family affairs. They are ancient, archaic, reach our ancestors, our true first Parents, those Indo-Europeans: Hittite, Vedic Aryans, Greeks, Romans, Germans, Celts, Slavs, Balts… The relations between different peoples in Europe, our holy land, are sometimes difficult—between Germans and Celts for example (in Ireland and the British Isles), or between southern Roman and Germanics, Slavic and Germanics or between them and the Balts. Our millennial affairs. No outsider is invited to this reunion, it is only for our ancestral peoples. No outsider has here any word, any ear, voice or vote.

These authors I am referring to are Jewish before being French, German, Spanish, or Russian, and only their “nation” moves them—not Europe or its people or their nations. Like Christians or Muslims, they are foreigners in any country or region. They can only speak from the position of the stateless. They have no nation but the Jewish community, or Muslim (the umma). These are their unique perspectives. They have nothing, then, to say. They cannot speak but from outside, from their own language / experience / perspective. Moreover, we can always say, “Take care of your business”, of your “nation and leave us in peace.” “Put your whole exegesis on your ‘Peters’ and ‘Pauls,’ and leave alone Homer, Aristotle and Plato.” This is what Julian told the “Galileans.” Something similar we can tell these new apostles of our newly restored paganism: “Devote yourselves to censor and destroy your own traditions and customs, and leave alone our philosophers and our entire culture.”

Jewish intellectuals among us don’t introduce themselves as Jews but as Westerners and seek to pass as ordinary citizens in appearance, indistinguishable from others (it is important, for their strategy, that we see them as French, German, or American, not as Jews). Mimicry. No Judaic displays or public fanfare. Rather: atheists, agnostics, heterodox, or simply “progressive” or “leftists” (terms that define much of the West). Their work is aimed at Westerners in general. In any case, these intellectuals, I say, never stop being Jews.

In their eternal double game—like aliens who are in any land (except in Israel); their dual nationality, double talk, dual mentality, dual language, double intention; their diabolism, forked tongue, their poison, they can not help it. Before being French, Russians, Germans or Americans, they’re Jews. The Jewish perspective never leaves them. The country or the Jewish nation is the transnational Jewish community, as is the case with Muslims and their umma, and would also happen to Christians and their community (the “people” of the god of the Jews) if they were consistent with their “faith.”

We must return to speak of Jewish philosophy, or Jewish thought, make them out of the current European thinkers (Kant, Hegel, Nietzsche, Heidegger) as we do with medieval philosophy, where we distinguish Jewish thought, European (mostly Christian) and Muslim. There is a contemporary “literature” or “writing” in the West we might call Jewish or Hebrew—for its content, references, fundamental concepts, for their “masters.” Topics, quotes, and Jewish authors (ancient, medieval, modern, and contemporary) are common in these scriptures.

The current Jewish thinkers navigate with the masthead of the most notable European thinkers of the past two hundred years (Kant, Hegel, Nietzsche, and Heidegger mainly) all the while guided by Jewish thinkers—Marx, Freud, Levinas, Adorno… These are the thinkers who form their conscience, they say. And the consciousness of much of today’s Europeans, unfortunately for us.

Wrapped in gentle nibbles, with a bit of Kant, Hegel, Nietzsche and Heidegger they make us swallow handfuls of Jewish issues, we are Judaized—again. Something “sweet” on the tip of the spoon to deceive, something different, something other than what they would have us swallow, something familiar for us not to distrust. As with children. Little by little, until they get used. After that they may withdraw the little sweet, other than Jewish. The art of Derrida. The floured paw hovering below the door. Jewish Scripture for Europeans or western Gentiles, for the European “cousins.” Like the old Judeo-Messianism.

The Jew always makes an appearance with an air of triumph to gentile “confusion”—as deus ex machina, as Socrates in the (rigged) Platonic dialogues. Go to the Derrida webpage, see and check. Texts on Marx, Freud, Benjamin and Levinas; Jewish characters and Jewish allusions, ancient and modern everywhere (article, interview, conference). Jewish writing—Jewish authors, Jewish issues, Jewish concerns, Jewish disquisitions, Jewish Byzantinism, Kabala, Talmud, Messianism. Self-centeredness in short. Megalomania: all about the Jews and their small world.

Do not forget they hold conferences and meetings of philosophy, of thought, strictly Jewish. Meetings in which a non-Jew, I presume, cannot participate except as a guest. Many of the topics and authors are, however, worldwide (Marxism, phenomenology, psychoanalysis, the Frankfurt School, Benjamin, Derrida…). Authors and philosophical topoi governing, today, much of European and western thought. They are the main current of thought, we might say. They have taken over. The list of Jewish authors whose narrative is relevant to our contemporary culture is excessive.

They do not use exclusively Jewish sources. As said, they are combined with certain doses of the aforementioned European authors. But we notice that these uses are rather to flag, to mark, to marginalize, to set them aside, to distinguish they from them. They fight ultimately against these texts (these authors): they strike them, delete them, make them void—seek their annulment, beat them, disconnect from them we might say, deprive of their strength, power, utility, functionality and present value; spoil them, block the outputs, cut the roads…

I think of the work done with Nietzsche—the pruning. The Nietzsche of Blanchot, Klossowski, Foucault, Deleuze, Lyotardt, Derrida, Vattimo. The post-modern. Weak thought. Weakened off thought, exhausted, dying, end. Nihilism in his misery. This scenario is not noticed in the Jewish front: it has another perspective. They have made that European thinkers rush, throw themselves into the abyss. They contemplate self-extinction. Objective nearly fulfilled.

It is the white Europe, of course, the final destination of these maneuvers and attacks; it is this Europe what he wants weakened, canceled, extinguished… deleted, gone, disappeared (as Sumer and Egypt disappeared). To turn Europe into something spooky, a dim memory.

Say there is a war between European thought and Jewish thought: Darwin and Nietzsche on the one hand, and Marx and Freud on the other (for simplicity). We have sociologies and anthropologies opposing each other. Opposing worlds. It’s a war of words, cultural, symbolic, even of the media. It is a struggle for dominance. Consider if Derrida’s writing is not raised as a fight against certain traditions and European institutions to influence the future of these institutions and traditions. The goal is to take over, to dominate, to possess. Those are “positions” in a fight. It is a war.

Today it is the entire European thought (from the Greek, from Homer) the demonized, which is under suspicion, the defeated, we could say. It’s all ancient European culture which is in question and is in danger of disappearing.

The future of European thinking (and being) is settled these days, although many of the “professionals” are not aware of it, do not realize they are already involved in this fight either one side or the other. You have to ask, what is the dominant thought? Which authors dominate or lead? It is an ideological struggle, a struggle in the heavens. Is the battle for Europe.

The objective is to take the head atop the Citadel (the Acropolis), the government centers, to drive, to lead. Like some retroviruses penetrating the nucleus of cells manage to enter the DNA and from it, replicate using mobile devices. The “replication” of the narrative from the core. Replicants. Cybernetics and the machinery or the social body.

The Jews try to dominate the whole field of thought, to definitely Judaize European philosophical thought, economics, politics, ethics, psychologies, anthropologies. They have spread in all fields of knowledge and culture. We go around figures and pathways of Jewish reflection, created by Jews: this is the intention.

For the achievement of this purpose, it is essential that Europeans and Westerners do not suspect for a moment that they are reading Jewish press, Jewish literature and Jewish thought, or watching Jewish movies (or myths propagated by Jews as the new Zion in Matrix). There are a number of clearly Jewish “products” that pass for art and culture for the mass, purportedly Western. We consume kosher culture prepared especially for Gentiles without knowing it.

Like when the old Judeo-Messianic Judaism—an ad hoc Judaism for European gentiles (no circumcision, no food requirements, and everything else—the god, the Jewish god, the Jewish holy book, the Jewish holy land…).

It is the propaganda of literature and art what we always have with Jews. They propagate themselves. They take care of themselves. They sell themselves; they are offered, promoted, one to each other. Is their art, the Phoenician art, Semitic art.

What they have always tried is how to survive, and always master, the strange land and even influence the life and work of the goyim. Among Semites it is always the search, anywhere, the transformation of the culture of the host to make it more favorable to their own interests.

Presently they win the battle in the minds and hearts of Europeans and Westerners. Incomprehensibly, their self-destructive and harmful slogans are in the air; their deadly conceptual beads. There are many Conversos or supporters that do not know they are, or are not taken by such (Marxists, Freudians, Derridans, universalists internationalists, multiculturalists…), those who leave their gold and flaunt the blackest chump.

Oh, simple, naive, gullible, trusting Europeans! Young, new, latest, inexperienced, adolescent race! When will you attain some maturity?

The recent Jewish cultural or intellectual contribution? It’s a room, four walls and a built-in insidious roof, slowly and laboriously from Marx to Derrida, the “intellectual” legacy or Jewish gift for future generations of poisoned Europe: a receptacle, a cell, a hideout. The new canonical texts and authors, the new “Parents” of the new European community or ecclesia—architects of this new Zion, the new Matrix. Is this our fate, the fate of our heirs? Once again enclosed within four walls? To live in the shade, under the roof of this minimum precinct—denying us space and horizon and preventing us from seeing our skies? Will this blackened and dirty roof be our single “heaven”? Nausea. Repugnance. The “universe,” the “world” of Marx, Kafka, Freud, Lukacs, Trotsky, Benjamin, Arendt, Adorno, Levinas, Derrida… The shadowy Jewish world; its unbreathable atmosphere, impure.

Just as the Judeo-Messianic “new testament,” the whole Jewish world came over us (from which we have not left), and with the discourse of Marx, Freud, Levinas, Benjamin, and Derrida we are returned back to that world. The one leads to the other. We are stopped, paralyzed, retained in their maze for centuries. We did not leave their tight and tedious world.

Jewish “intelligentsia” attempts to shape and direct our lives for millennia. The brand new testament; the new apostles of the Gentiles. A new Jewish Messianic millennium, a new supreme winter. This is the threat.

The “Holocaust” is now their Golgotha, their sign, their cross, their pale banner.

The sky is brick-worked, certainly. Our skies are paved with brick through the Jewish skies and Judeo-Messianic Jews. Now we have a new brickwork, and both the old and new are preserved. A double brickwork and double key. In both cases the keys are held by Jews.

These “heavens” are the ways of salvation made by European Jews to the Gentiles. Both destroy us, destroy our being. Both the old Judeo-Messianism as the new—the brand new testament.

Clairvoyance and courage I wish to my own to get out of this mess, to de-brickworking these skies outside, to shoot down these walls, to restore the light of our skies, our breathing of pure air. To win in the end.

We must be stronger than the disease, more vigorous than the evil that invades us. It is time to frustrate the plans of these charlatans, these tricksters, these cheaters, these imposters and usurpers.

Until next time,

Manu