Finally, one white nationalist site, the webzine Counter Currents, has published a book review of the subject we consider most important, the destruction of the Greco-Roman world by early Christians.

Finally, one white nationalist site, the webzine Counter Currents, has published a book review of the subject we consider most important, the destruction of the Greco-Roman world by early Christians.

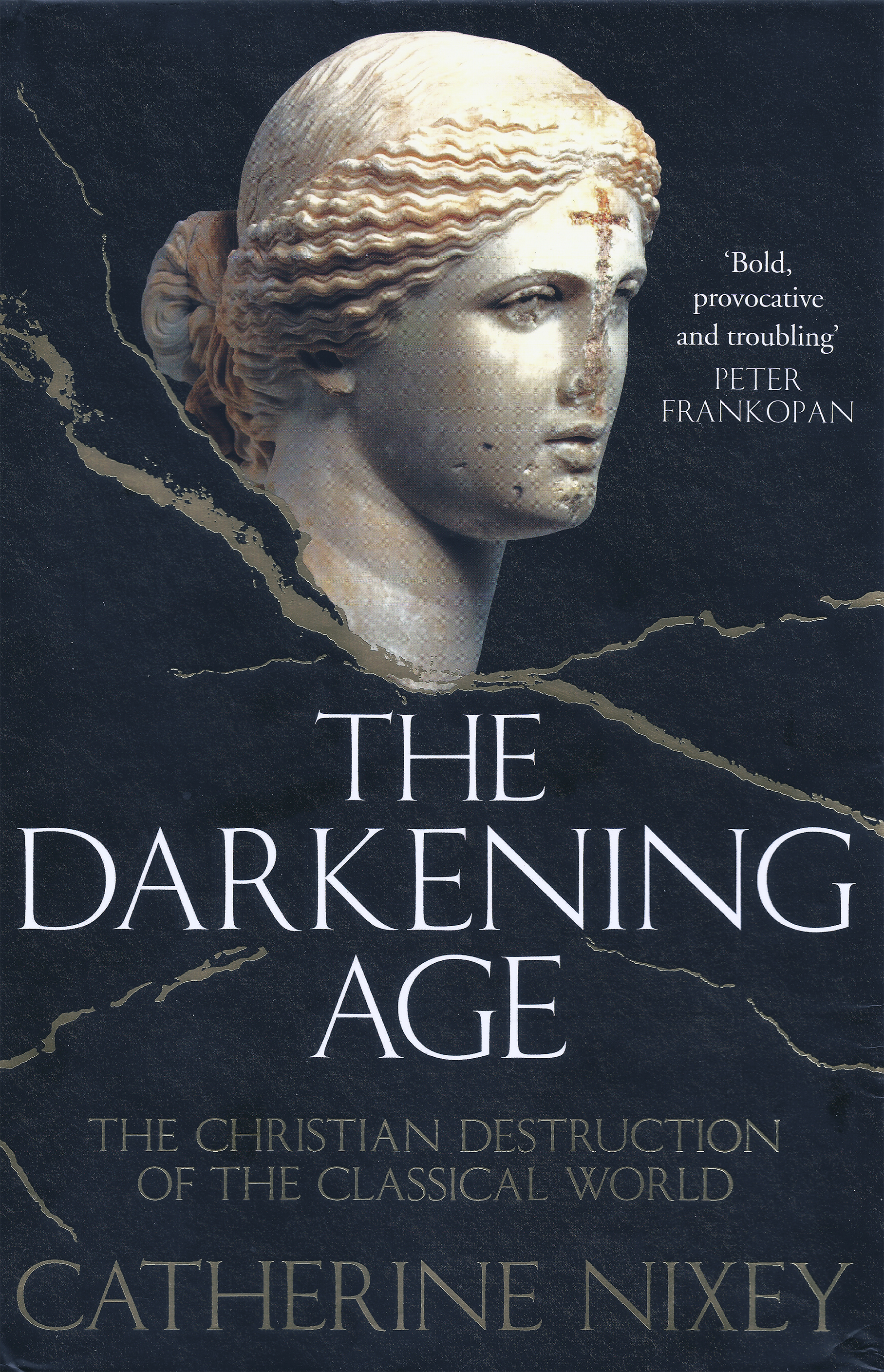

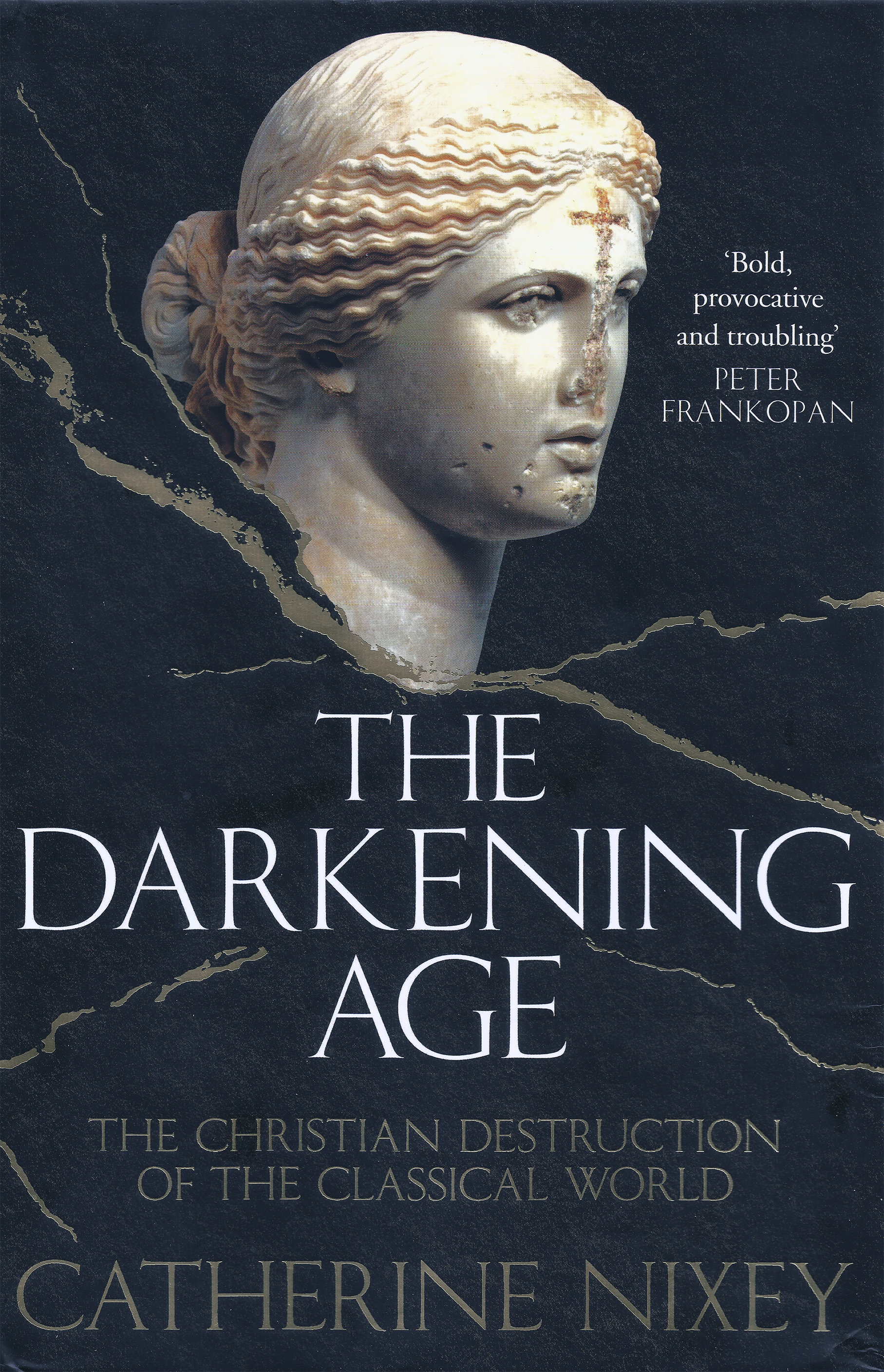

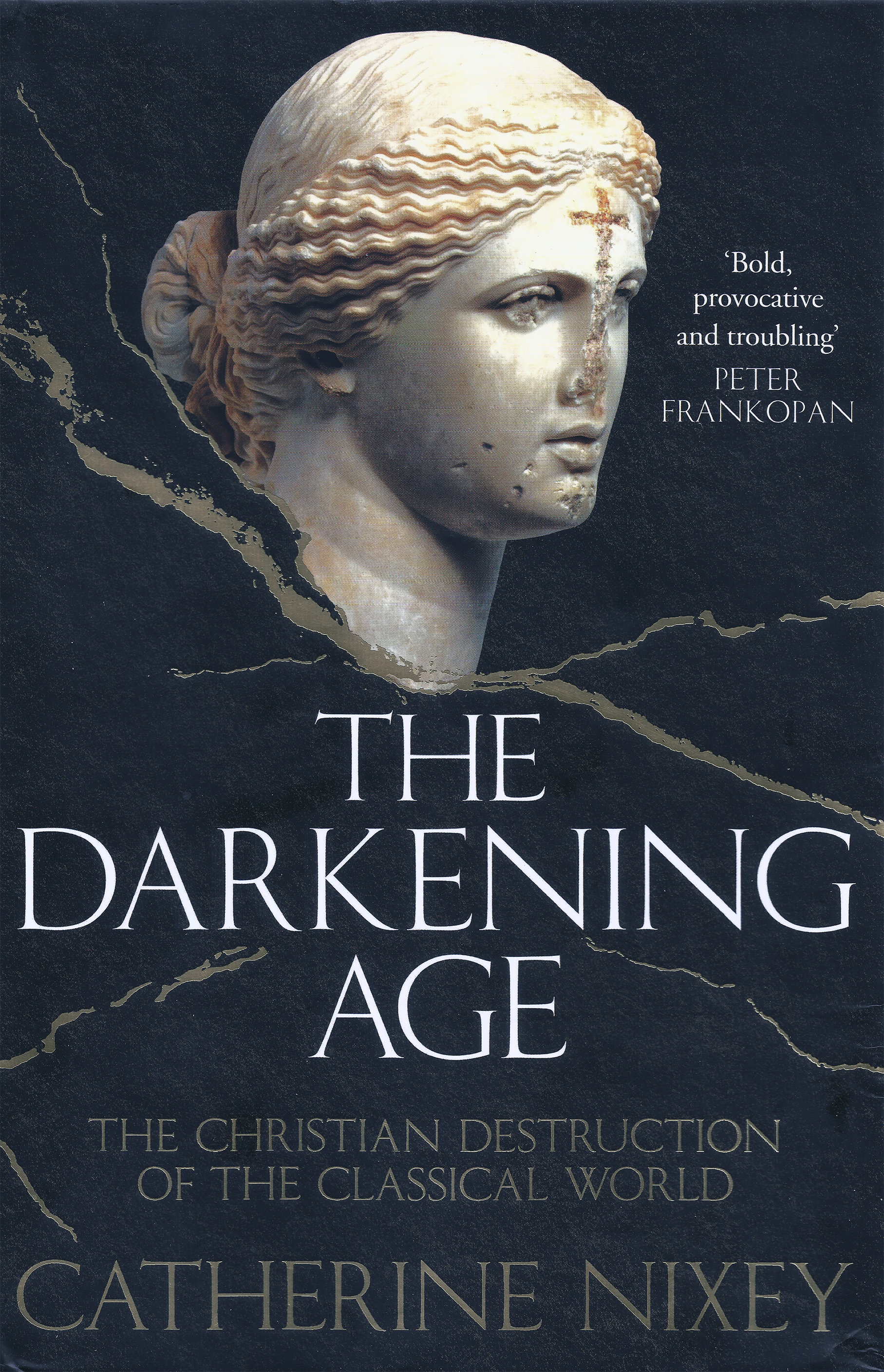

I refer to A. Graham’s review of the 2018 American edition of Catherine Nixey’s The Darkening Age: The Christian Destruction of the Classical World (Boston: Houghton Mifflin Harcourt).

However, the commentariat of Counter Currents seems ignorant of Evropa Soberana’s eureka essay that I have been advertising in the masthead of this site (see especially these paragraphs). Perhaps a visitor of The West’s Darkest Hour may wish to link Soberana’s essay, that I translated from Spanish to English, in that thread of Counter Currents (for example: here)?

This is probably the most important topic of the whole white nationalist blogosphere. If Aryans remain ignorant of the very roots of Judaic infection they won’t be able to find a cure, as an incomplete diagnosis translates into an incomplete or imperfect medicine.

Category: Darkening Age (book)

Saint Apollonia destroys a Greco-Roman sculpture, Giovanni d’Alemagna, c. 1442-1445.

The saint calmly ascends to the ‘idol’, hammer in hand. Hagiographies frequently praised the flair with which saints smashed ancient temples and centuries-old statues.

In ‘The Most Magnificent Building in the World’, chapter six of The Darkening Age: The Christian Destruction of the Classical World, Catherine Nixey wrote:

At the end of the first century of Christian rule, the Colosseum still dominated Rome and the Parthenon towered above Athens. Yet when writers of this period discuss architecture, these aren’t the buildings that impress them. Instead, their admiration is drawn by another structure in Egypt. This building was so fabulous that writers in the ancient world struggled to find ways to convey its beauty. ‘Its splendour is such that mere words can only do it an injustice,’ wrote the historian Ammianus Marcellinus. It was, another writer thought, ‘one of the most unique and uncommon sights in the world. For nowhere else on earth can one find such a building.’ Its great halls, its columns, its astonishing statues and its art all made it, outside Rome, ‘the most magnificent building in the whole world’. Everyone had heard of it.

No one has heard of it now. While tourists still toil up to the Parthenon, or look in awe at the Colosseum, outside academia few people know of the temple of Serapis. That is because in AD 392 a bishop, supported by a band of fanatical Christians, reduced it to rubble.

It is easy to see why this temple would have attracted the Christians’ attention. Standing at the top of a hundred or more marble steps, it had once towered over the startling white marble streets below, an object to incite not only wonder but envy. While Christians of the time crammed into insufficient numbers of small, cramped churches, this was a vast—and vastly superior—monument to the old gods. It was one of the first buildings you noticed as you sailed towards Alexandria, its roof looming above the others, and one that you were unlikely to forget.

Walk on and, just behind the porticoes of the inner court, you would have found yourself in a vast library—the remnants of the Great Library of Alexandria itself. The library’s collection was now stored here, within the temple precinct, for safekeeping. This had been the world’s first public library; and its holdings had, at its height, been staggering, running into hundreds of thousands of volumes. Like the city itself, the collection had taken several knocks over the years, but extensive collections remained.

Like all statues of this size, Serapis was made of a wooden structure overlaid with precious materials: the god’s profile was made of glowing white ivory; his enormous limbs were draped in robes of metal—very probably gold. The statue was so huge that his great hands almost touched either side of the room…

To the new generation of Christian clerics, however, Serapis was not a wonder of art; or a much-loved local god. Serapis was a demon… Fierce words—but Christians had been fulminating in this way for decades and polytheists had been able to ignore them. But the world was changing. It was now eighty years since a Christian had first sat on the throne of Rome and in the intervening decades the religion of the Lamb had taken an increasingly bullish attitude to all those who refused it…

One day, early in AD 392, a large crowd of Christians started to mass outside the temple, with Theophilus at its head. And then, to the distress of watching Alexandrians, this crowd had surged up the steps, into the sacred precinct and burst into the most beautiful building in the world.

And then they began to destroy it.

Theophilus’s righteous followers began to tear at those famous artworks, the lifelike statues and the gold-plated walls. There was a moment’s hesitation when they came to the massive statue of the god: rumour had it that if Serapis was harmed then the sky would fall in. Theophilus ordered a soldier to take his axe and hit it. The soldier struck Serapis’s face with a double-headed axe. The god’s great ivory profile, blackened by centuries of smoke, shattered.

The watching Christians roared with delight and then, emboldened, surged round to complete the job. Serapis’s head was wrenched from its neck; the feet and hands were chopped off with axes, dragged apart with ropes, then, for good measure, burned.

As one delighted Christian chronicler put it, the ‘decrepit, dotard’ Serapis ‘was burned to ashes before the eyes of the Alexandria which had worshipped him’. The giant torso of the god was saved for a more public humiliation: it was taken into the amphitheatre and burned in front of a great crowd. ‘And that,’ as our chronicler notes with satisfaction, ‘was the end of the vain superstition and ancient error of Serapis.’

A little later, a church housing the relics of St John the Baptist was built on the temple’s ruins, a final insult to the god—and to architecture. It was, naturally, an inferior structure. According to later Christian chronicles, this was a victory. According to a non-Christian account, it was a tragedy…

Nothing was left. Christians took apart the temple’s very stones, toppling the immense marble columns, causing the walls themselves to collapse. The entire sanctuary was demolished with astonishing rapidity; the greatest building in the world was ‘scattered to the winds’. [1]

The tens of thousands of books, the remnants of the greatest library in the world, were all lost, never to reappear…

Far more than a temple had gone. As the news of the destruction spread across the empire, something of the spirit of the old culture died too. As one Greek professor wrote in despair: ‘The dead used to leave the city alive behind them, but we living now carry the city to her grave.’

_________

[1] Note of the Ed.: See the remains today of the Serapeum of Alexandria: here.

Darkening Age, 8

These are the last words of chapter five of The Darkening Age: The Christian Destruction of the Classical World:

A little over a century later, AD 423, the Christian government announced that any pagans who still survived were to be suppressed. Though, it added confidently—and ominously: ‘We now believe that there are none’.

Presently I am reviewing the syntax of the first seventy entries I have posted in this site of Karlheinz Deschner’s Kriminalgeschichte des Christentums. Once I finish the review I’ll provide a PDF. The reviewed translation will also be available in book form under the title Christianity’s Criminal History.

The present book is an abridged translation of the first volume of Karlheinz Deschner’s ten-volume Kriminalgeschichte des Christentums. The original volume with hundreds of endnotes (every quotation is accompanied by the proper reference), and whose first chapter on the Old Testament is longer than our brief excerpts, was published in German in 1986. My hope is that this preliminary translation is only the first step for a more academic translation of Deschner’s magnum opus. Furthermore, in this translation I took the liberty to add several illustrations and even replace many instances of the author’s use of the word ‘pagan’, which is derogatory Christian Newspeak, with terms like ‘Hellenist’ or ‘advocate of Greco-Roman culture’.

The present book is an abridged translation of the first volume of Karlheinz Deschner’s ten-volume Kriminalgeschichte des Christentums. The original volume with hundreds of endnotes (every quotation is accompanied by the proper reference), and whose first chapter on the Old Testament is longer than our brief excerpts, was published in German in 1986. My hope is that this preliminary translation is only the first step for a more academic translation of Deschner’s magnum opus. Furthermore, in this translation I took the liberty to add several illustrations and even replace many instances of the author’s use of the word ‘pagan’, which is derogatory Christian Newspeak, with terms like ‘Hellenist’ or ‘advocate of Greco-Roman culture’.

But why reproduce excerpted passages from Deschner’s opus in the first place?

White nationalists are aware of the Jewish problem. But very few are aware that Jewish subversion is not the product of spontaneous generation but of a religion of Semitic origin: Christianity. Who among the white nationalists knows the real history of Christianity? Who is aware that Christian fanatics destroyed, literally, the Greco-Roman world? As Catherine Nixey put it in The Darkening Age: The Christian Destruction of the Classical World:

In a spasm of destruction never seen before—and one that appalled many non-Christians watching it—during the fourth and fifth centuries, the Christian Church demolished, vandalized and melted down a simply staggering quantity of art. Classical statues were knocked from their plinths, defaced, defiled and torn limb from limb. Temples were razed to their foundations and burned to the ground. A temple widely considered to be the most magnificent in the entire empire was levelled.

Many of the Parthenon sculptures were attacked, faces were mutilated, hands and limbs were hacked off and gods were decapitated. Some of the finest statues on the whole building were almost certainly smashed off then ground into rubble that was then used to build churches.

Books—which were often stored in temples—suffered terribly. The remains of the greatest library in the ancient world, a library that had once held perhaps 700,000 volumes, were destroyed in this way by Christians. It was over a millennium before any other library would even come close to its holdings. Works by censured philosophers were forbidden and bonfires blazed across the empire as outlawed books went up in flames.

Most white nationalists ignore the ISIS-like history of early Christianity right after Constantine handed over the Roman Empire to his bishops. They know only the martyr myths, the pious legends and the lies they told us as children educated in the Christian faith.

Karlheinz Deschner (1924-2014) was a liberal German. He spent the first sixty years of his life investigating the history of the Catholic Church before starting the ten volumes of his Kriminalgeschichte series, which only ended at ninety. It is a more complete treatise, or encyclopaedia I would dare to say, about the real history of Christianity than Nixey’s The Darkening Age.

I started reading Deschner in 2002 when I was also a liberal. I would not wake on the Jewish question until 2010. But Deschner, like all Germans of our times who aspire to see their books in the bookstores, never woke up. He even criticised the most notorious ‘anti-Semites’ in early Church history. This said, the difference between Deschner and liberal theologians like Hans Küng (The Church) and conservative historians like Paul Johnson (A History of Christianity) is that Küng and Johnson concealed a great deal of Christianity’s criminal history. It is remarkable how a scholar who abandoned Christianity, like Deschner, was capable to criticise it in a way that Küng, Johnson, and the most prominent Christian intellectuals would never dream of.

After awakening to the realities of the Jewish problem I realised that Deschner’s information, despite his mistaken point of view, can be rescued. It only has to be processed through the filter of someone who has awakened on the Jewish question. Had Germany won the war, Deschner, who appears in a previous page in Nazi uniform, could have written his history from the National Socialist point of view.

C.T.

July of 2018

Yesterday I said that in the third volume of the series Christianity’s Criminal History, ‘The Ancient Church: Forgery, Brainwashing, Exploitation, Annihilation’, Deschner argues that the tales of Christian martyrs in early Christianity were grossly exaggerated, and that I planned in the future to translate some passages of it. But the impatient English reader can go to his nearest library and read chapter four of Catherine Nixey’s recently published The Darkening Age, ‘On the Small Number of Martyrs’.

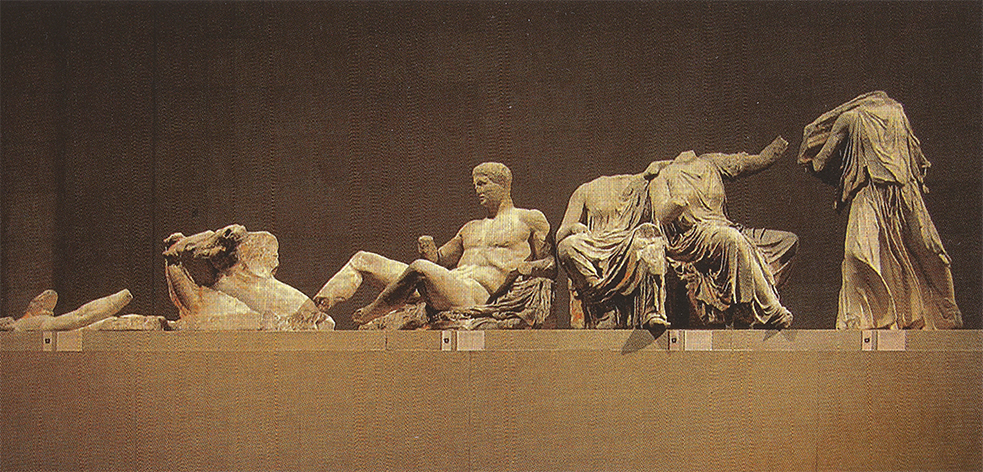

Within that chapter are included the images in colour that illustrate the book. Above, you can see the surviving figures of the Parthenon in Athens. Nixey says that these figures ‘were almost certainly mutilated by Christians who believed them to be “demonic”. The central figures of the group are missing, probably levered off the ground into rubble to build a Christian church’ (image facing page 57).

In chapter three of The Darkening Age: The Christian

Destruction of the Classical World, Catherine Nixey wrote:

A few decades after Celsus wrote On the True Doctrine, an even more monumental assault was made on the Christian faith by another Greek philosopher. It shocked the Christian community with its depth, breadth and brilliance. Yet today this philosopher’s name, like Celsus’s, has been all but forgotten. He was, we know, called Porphyry. We know that his attack was immense—at least fifteen books; that it was highly erudite and that it was, to the Christians, deeply upsetting. We know that it targeted Old Testament history, and poured scorn on the prophets and on the blind faith of Christians…

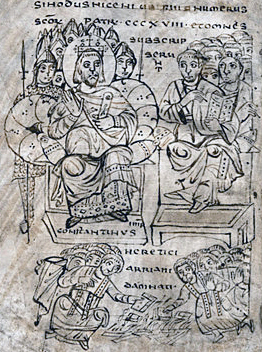

This much, then, is known—but not much more. And the reason we don’t know is that Porphyry’s works were deemed so powerful and frightening that they were completely eradicated. Constantine, the first Christian emperor—now famed for his edict of ‘toleration’—started the attack.

In a letter written in the early part of the fourth century; he heaped odium on the long-dead philosopher, describing him as ‘that enemy of piety’; an author of ‘licentious treatises against religion’. Constantine announced that he was henceforth ‘branded with infamy’, overwhelmed ‘with deserved reproach’ and that his ‘impious writings’ had been destroyed.

In the same letter Constantine also consigned the works of the heretic, Arius, to the flames and announced that anyone who was found hiding one of Arius’s books would be put to death.

Constantine burning the above-mentioned books

(illustration from a book of canon law, ca. 825).

A century or so later, in AD 448, Porphyry’s books were burned again, this time on the orders of the Christian emperors Theodosius II and Valentinian III.

Celsus and Democritus

Note of the Ed.: Celsus was Christianity’s first great critic. The following is an excerpt from Nixey’s chapter ‘Wisdom is Foolishness’:

Celsus did not soften his attack either. This first assault on Christianity was vicious, powerful and, like Gibbon, immensely readable. Yet unlike Gibbon, today almost no one has heard of Celsus and fewer still have read his work. Because Celsus’s fears came true. Christianity continued to spread, and not just among the lower classes. Within 150 years of Celsus’s attack, even the Emperor of Rome professed himself a follower of the religion.

Celsus did not soften his attack either. This first assault on Christianity was vicious, powerful and, like Gibbon, immensely readable. Yet unlike Gibbon, today almost no one has heard of Celsus and fewer still have read his work. Because Celsus’s fears came true. Christianity continued to spread, and not just among the lower classes. Within 150 years of Celsus’s attack, even the Emperor of Rome professed himself a follower of the religion.

What happened next was far more serious than anything Celsus could ever have imagined. Christianity not only gained adherents, it forbade people from worshipping the old Roman and Greek gods. Eventually, it simply forbade anyone to dissent from what Celsus considered its idiotic teachings. To pick just one example from many, in AD 386, a law was passed targeting those ‘who con tend about religion’ in public. Such people, this law warned, were the ‘disturbers of the peace of the Church’ and they ‘shall pay the penalty of high treason with their lives and blood’.

Celsus paid his own price. In this hostile and repressive atmosphere his work simply disappeared. Not one single unadulterated volume of the work by Christianity’s first great critic has survived. Almost all information about him has vanished too, including any of his names except his last; what prompted him to write his attack; or where and when he wrote it. The long and inglorious Christian practice of censorship was now beginning.

However, by a quirk of literary fate, most of his words have survived. Because eighty-odd years after Celsus fulminated against the new religion, a Christian apologist named Origen mounted a fierce and lengthy counter-attack. Origen was rather more earnest than his occasionally bawdy classical adversary. Indeed, it was said that Origen had even taken the words of Matthew 19:12 (‘For there are some eunuchs… which have made themselves eunuchs for the kingdom of heaven’s sake’) a little too much to heart and, in a fit of heavenly self-abnegation, castrated himself.

Ironically, it was the very work that had been intended to demolish Celsus that saved him. No books of Celsus have survived the centuries untouched, true—but Origen’s attack has and it quoted Celsus at length. Scholars have therefore been able to extract Celsus’s arguments from Origen’s words, which preserved them like flies in amber. Not all of the words—perhaps only seventy per cent of the original work has been recovered. Its order has gone, its structure has been lost and the whole thing, as Gibbon put it, is a ‘mutilated representation’ of the original. But nevertheless we have it…

In the ensuing centuries, texts that contained such dangerous ideas paid a heavy price for their ‘heresy’. As has been lucidly argued by Dirk Rohmann, an academic who has produced a comprehensive and powerful account of the effect of Christianity on books, some of the greatest figures in the early Church rounded on the atomists. Augustine disliked atomism for precisely the same reason that atomists liked it: it weakened mankind’s terror of divine punishment and Hell. Texts by philosophical schools that championed atomic theory suffered.

The Greek philosopher Democritus had perhaps done more than anyone to popularize this theory—though not only this one. Democritus was an astonishing polymath who had written works on a breathless array of other topics. A far from complete list of his titles includes: On History; On Nature; the Science of Medicine; On the Tangents of the Circle and the Sphere; On Irrational Lines and Solids; On the Causes of Celestial Phenomena; On the Causes of Atmospheric Phenomena; On Reflected Images… The list goes on. Today Democritus’s most famous theory is his atomism. What did the other theories state? We have no idea: every single one of his works was lost in the ensuing centuries. As the eminent physicist Carlo Rovelli recently wrote, after citing an even longer list of the philosopher’s titles: ‘the loss of the works of Democritus in their entirety is the greatest intellectual tragedy to ensue from the collapse of the old classical civilisation’…

Celsus wasn’t merely annoyed at the lack of education among these people. What was far worse was that they actually celebrated ignorance. They declare, he wrote, that ‘Wisdom in this life is evil, but foolishness is good’—an almost precise quotation from Corinthians. Celsus verges on hyperbole, but it is true that in this period Christians gained a reputation for being uneducated to the point of idiotic; even Origen, Celsus’s great adversary, admitted that ‘the stupidity of some Christians is heavier than the sand of the sea.’

Or

Combating the ultimate meme: God

In the chapter ‘The Battleground of Demons’ Nixey wrote:

But however alarming the demons of fornication may have been, the most fearsome demons of all were to be found, teeming like flies on a corpse, around the traditional gods of the empire. Jupiter, Aphrodite, Bacchus and Isis; all of them, in the eyes of these Christian writers, were demonic.

In sermon after sermon, tract after tract, Christian preachers and writers reminded the faithful in violently disapproving language that the ‘error’ of the pagan religions was demonically inspired. It was demons who first put the ‘delusion’ of other religions into the minds of humans, these writers explained.

It was demons who had foisted the gods upon ‘the seduced and ensnared minds of human beings’. Everything about the old religions was demonic. As Augustine thundered: ‘All the pagans were under the power of demons. Temples were built to demons, altars were set up to demons, priests ordained for the service of demons, sacrifices offered to demons, and ecstatic ravers were brought in as prophets for demons.’

Let’s return the favour.

The worst mistake that the white race has made is to have drunk the hemlock of the Bible. The Torah may be good for the Jews insofar as it teaches them ethnocentrism for the Hebrews and the genocide of the gentiles. But the Gospel is fatal to whites insofar as it teaches them to indiscriminately love the Other. The Torah added to the Gospel results in the Biblical United States and in Neochristian Europe. The suicidal standards of values of the philo-Semitic US and the secular EU are exactly the same.

In order to break the spell of the axiological hypnosis of the West, we must comply with the sixth article of the ‘Law against Christianity’ by Nietzsche:

§ 6 — The ‘holy’ history should be called by the name it deserves, the cursed history; the words ‘God’, ‘saviour’, ‘redeemer’, ‘saint’ should be used as terms of abuse, to signify criminals.

This initiative of mine, taking Nietzsche’s law seriously as payback for what the Xtians did (cf. Nixey’s quote above), reminds me of something I read in Siege. James Mason said there was a quantum leap from what Rockwell preached—the well-meaning but mistaken commander who placed the Nazi flag side by side the American flag—and the revolutionary proposal. But while Mason realised that the American government must be overthrown through armed revolution, he did not depart from the religion of those who precisely form the American government.

The real breakthrough in my opinion lies in rebelling against the ultimate meme: the idea of God. And that can only be done with a counter-meme: using the word ‘God’ as an insult, as it is obvious that for the Western mentality ‘God’ means nothing else than the god of the Jews.

I came to these conclusions after reading the recent transcript of the first podcast of this site, ‘Christianity is White Genocide’. More than what Linder said I liked what Walsh said. But even in what he said, that it was unclear if God existed, there is a residue of the brainwashing, as it is obvious that the god of the Jews doesn’t exist.

That same residue persisted in the philosophes of the Enlightenment. Not being Jew-wise, d’Alembert, Diderot, Hume, Kant, Montesquieu, Rousseau, Condorcet, Voltaire, Benjamin Franklin and others did not understand the psyop that monotheism represented for Europe. Some of them even transformed the god of the Jews into the nebulous god of the deists but never dared to insult the very idea of ‘God’.

Had the so-called Enlightenment understood the ultimate meme, which reminds me of what Heisman✡ said in some of the twelve entries I recently devoted to his book, they would have developed the sixth article of Nietzsche’s law ever since:

§ 6 — The ‘holy’ history should be called by the name it deserves, the cursed history; the words ‘God’, ‘saviour’, ‘redeemer’, ‘saint’ should be used as terms of abuse, to signify criminals.

Anti-Christian German Nazis and William Pierce are dead. It seems sad to me that no one has taken Pierce’s torch in North America at the moment. Or maybe I’m wrong. From the strictly geographical point of view I am in North America. But it is still sad that no native English speaker has realised that they have to fight the ultimate meme of the Jews, the haughty idea of ‘God’, monotheism: that the god of the Jews is the only god that exists.

In the chapter ‘The Invisible Army’ of The Darkening Age: The Christian Destruction of the Classical World, Catherine Nixey talks about how, once the Christians seized the Weltanschauung of the Roman Empire, a demonological hysteria arose that led Christians to a state of virtual paranoia.

It is curious how Christians today ignore fundamental aspects of the history of their religion. When not long ago I told a friend about the demons that persecuted St Anthony the Great (251-356), I found out that he knew nothing about the subject: something so popular throughout Christendom that the ‘temptations of St Anthony’ permeated European imagination for centuries.

Saint Anthony was the founding father of the monastic life: one of the most influential men in Christianity. As a teenager I saw images like this painting by Grünewald. I knew that the demons (temptations) that the ascetic fought were sexual thoughts that he, who had taken a vow of chastity, had to fight.

Saint Anthony was the founding father of the monastic life: one of the most influential men in Christianity. As a teenager I saw images like this painting by Grünewald. I knew that the demons (temptations) that the ascetic fought were sexual thoughts that he, who had taken a vow of chastity, had to fight.

The case of St Anthony, which Nixey details in the first chapter of her book, was not isolated. My ignorant Catholic friend, who did not know the history of this very influential man, could think that all that lies now in the remote past.

Not really. When I was a teenager my mother used to come to my room with holy water while I slept because she thought the devil had gotten into me. My sister was terrified to see, in puberty, the movie The Exorcist on the big screen because she believed that the devil really existed.

Decades later, when my brother wanted to divorce, my father wrote him a letter saying that the devil was hanging around tempting them to divorce. My mother even summoned her children on one occasion to tell us that, recovering from an operation, she had committed the blunder of challenging the devil so that he would not mess with her children, and that the devil had insinuated her presence in front of her. A priest scolded her: the devil should never be challenged: only ignored. More recently, some nuns told my mother that the noises they heard in their monastery were angry demons due to the saintly work of the nuns.

This is not the place to narrate how the Catholicism at home was a fundamental factor in the destruction of my adolescent life. I would just like to point out that, in Nixey’s chapter, it is described how, once the classical culture was destroyed, the Europeans were under perpetual attack by Satan and his fearsome soldiers, the demons. Their aim, in European imaginary, was to drag them all to damnation.

Currently a residue of this paranoia is only seen in the most traditional Christian families.

‘That all superstition of pagans and heathens should be annihilated is what God wants, God commands, God proclaims.’

— St Augustine

This was no time for a philosopher to be philosophical. ‘The tyrant’, as the philosophers put it, was in charge and had many alarming habits. In Damascius’s own time, houses were entered and searched for books and objects deemed unacceptable. If any were found they would be removed and burned in triumphant bonfires in town squares. Discussion of religious matters in public had been branded a ‘damnable audacity’ and forbidden by law. Anyone who made sacrifices to the old gods could, the law said, be executed. Across the empire, ancient and beautiful temples had been attacked, their roofs stripped, their treasures melted down, their statues smashed. To ensure that their rules were kept, the government started to employ spies, officials and informers to report back on what went on in the streets and marketplaces of cities and behind closed doors in private homes. As one influential Christian speaker put it, his congregation should hunt down sinners and drive them into the way of salvation as relentlessly as a hunter pursues his prey into nets.

The consequences of deviation from the rules could be severe and philosophy had become a dangerous pursuit. Damascius’s own brother had been arrested and tortured to make him reveal the names of other philosophers, but had, as Damascius recorded with pride, ‘received in silence and with fortitude the many blows of the rod that landed on his back’. Others in Damascius’ s circle of philosophers had been tortured; hung up by the wrists until they gave away the names of their fellow scholars. A fellow philosopher had, some years before, been flayed alive. Another had been beaten before a judge until the blood flowed down his back.

The savage ‘tyrant’ was Christianity. From almost the very first years that a Christian emperor had ruled in Rome in AD 312, liberties had begun to be eroded. And then, in AD 529, a final blow had fallen. It was decreed that all those who laboured ‘under the insanity of paganism’—in other words Damascius and his fellow philosophers—would be no longer allowed to teach. There was worse. It was also announced that anyone who had not yet been baptized was to come forward and make themselves known at the ‘holy churches’ immediately, or face exile. And if anyone allowed themselves to be baptized, then slipped back into their old pagan ways, they would be executed.

For Damascius and his fellow philosophers, this was the end. They could not worship their old gods. They could not earn any money. Above all, they could not now teach philosophy. The Academy, the greatest and most famous school in the ancient world—perhaps ever—a school that could trace its history back almost a millennium, closed.

It is impossible to imagine how painful the journey through Athens would have been. As they went, they would have walked through the same streets and squares where their heroes—Socrates, Plato, Aristotle—had once walked and worked and argued. They would have seen in them a thousand reminders that those celebrated times were gone. The temples of Athens were closed and crumbling and many of the brilliant statues that had once stood in them had been defaced or removed. Even the Acropolis had not escaped: its great statue of Athena had been torn down.

Little of what is covered by this book is well-known outside academic circles. Certainly it was not well-known by me when I grew up in Wales, the daughter of a former nun and a former monk. My childhood was, as you might expect, a fairly religious one. We went to church every Sunday; said grace before meals, and I said my prayers (or at any rate the list of requests which I considered to be the same thing) every night. When Catholic relatives arrived we play-acted not films but First Holy Communion and, at times, even actual communion…

As children, both had been taught by monks and nuns; and as a monk and a nun they had both taught. They believed as an article of faith that the Church that had enlightened their minds was what had enlightened, in distant history, the whole of Europe. It was the Church, they told me, that had kept alive the Latin and Greek of the classical world in the benighted Middle Ages, until it could be picked up again by the wider world in the Renaissance. And, in a way, my parents were right to believe this, for it is true. Monasteries did preserve a lot of classical knowledge.

But it is far from the whole truth. In fact, this appealing narrative has almost entirely obscured an earlier, less glorious story. For before it preserved, the Church destroyed.

In a spasm of destruction never seen before—and one that appalled many non-Christians watching it—during the fourth and fifth centuries, the Christian Church demolished, vandalized and melted down a simply staggering quantity of art. Classical statues were knocked from their plinths, defaced, defiled and torn limb from limb. Temples were razed to their foundations and burned to the ground. A temple widely considered to be the most magnificent in the entire empire was levelled.

Many of the Parthenon sculptures were attacked, faces were mutilated, hands and limbs were hacked off and gods were decapitated. Some of the finest statues on the whole building were almost certainly smashed off then ground into rubble that was then used to build churches.

Books—which were often stored in temples—suffered terribly. The remains of the greatest library in the ancient world, a library that had once held perhaps 700,000 volumes, were destroyed in this way by Christians. It was over a millennium before any other library would even come close to its holdings. Works by censured philosophers were forbidden and bonfires blazed across the empire as outlawed books went up in flames.

Fragment of a 5th-century scroll

showing the destruction of the Serapeum

by Pope Theophilus of Alexandria

The work of Democritus, one of the greatest Greek philosophers and the father of atomic theory, was entirely lost. Only one per cent of Latin literature survived the centuries. Ninety-nine per cent was lost.

The violent assaults of this period were not the preserve of cranks and eccentrics. Attacks against the monuments of the ‘mad’, ‘damnable’ and ‘insane’ pagans were encouraged and led by men at the very heart of the Catholic Church. The great St Augustine himself declared to a congregation in Carthage that ‘that all superstition of pagans and heathens should be annihilated is what God wants, God commands, God proclaims!’ St Martin, still one of the most popular French saints, rampaged across the Gaulish countryside levelling temples and dismaying locals as he went. In Egypt, St Theophilus razed one of the most beautiful buildings in the ancient world. In Italy, St Benedict overturned a shrine to Apollo. In Syria, ruthless bands of monks terrorized the countryside, smashing down statues and tearing the roofs from temples.

St John Chrysostom encouraged his congregations to spy on each other. Fervent Christians went into people’s houses and searched for books, statues and paintings that were considered demonic. This kind of obsessive attention was not cruelty. On the contrary: to restrain, to attack, to compel, even to beat a sinner was— if you turned them back to the path of righteousness—to save them. As Augustine, the master of the pious paradox put it: ‘Oh, merciful savagery.’

The results of all of this were shocking and, to non-Christians, terrifying. Townspeople rushed to watch as internationally famous temples were destroyed. Intellectuals looked on in despair as volumes of supposedly unchristian books—often in reality texts on the liberal arts—went up in flames. Art lovers watched in horror as some of the greatest sculptures in the ancient world were smashed by people too stupid to appreciate them—and certainly too stupid to recreate them.

Since then, and as I write, the Syrian civil war has left parts of Syria under the control of a new Islamic caliphate. In 2014, within certain areas of Syria, music was banned and books were burned. The British Foreign Office advised against all travel to the north of the Sinai Peninsula. In 2015, Islamic State militants started bulldozing the ancient Assyrian city of Nimrud, just south of Mosul in Iraq because it was ‘idolatrous’. Images went around the world showing Islamic militants toppling statues around three millennia old from their plinths, then taking hammers to them. ‘False idols’ must be destroyed. In Palmyra, the remnants of the great statue of Athena that had been carefully repaired by archaeologists, was attacked yet again. Once again, Athena was beheaded; once again, her arm was sheared off.

I have chosen Palmyra as a beginning, as it was in the east of the empire, in the mid-380s, that sporadic violence against the old gods and their temples escalated into something far more serious. But equally I could have chosen an attack on an earlier temple, or a later one. That is why it is a beginning, not the beginning. I have chosen Athens in the years around AD 529 as an ending—but again, I could equally have chosen a city further east whose inhabitants, when they failed to convert to Christianity, were massacred and their arms and legs cut off and strung up in the streets as a warning to others.