Hail Pallas Athena, born from the head of Zeus,

Goddess of the city, giver of glorious victory.

Category: Athens

On the ‘Atomwaffen Division’

‘Satanism is alright. Depends on how you go about it. But then again, I’m more well read on the subject than most people. Most people get scared away and only go into the crust, rather than down to the core’. —Rape [penname], AWD Discord server, November 9, 2017.

Using a negative Christian symbol (Satan) to scare Christians, as the so-called Atomwaffen Division (AWD) does, should trigger the alarm signal in anyone wishing to recover the West. It is the reverse of using a positive Christian symbol (the hymn that Martin Luther composed) to please Christians, as in the case of another failed revolutionary, Harold Covington.

AWD with James Mason at the centre

When I see someone using satanic symbols the first thing that comes to my mind is: ‘A mental infant…!’

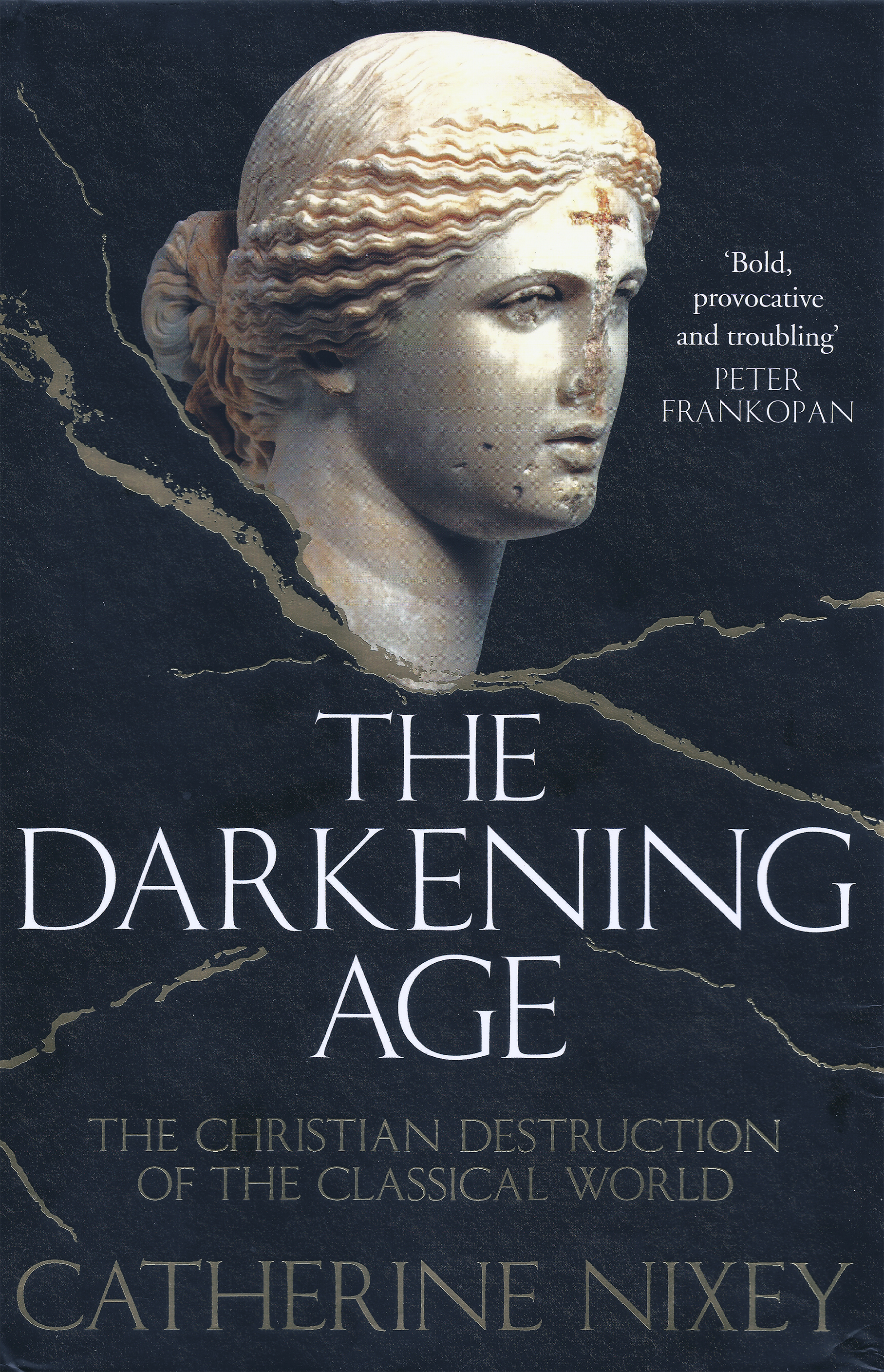

It should be obvious that if someone wants to start distancing himself from the religion of our parents, the distancing mustn’t be done childishly but maturely: assimilating books like that of the Spaniard Evropa Soberana about the psychological warfare that Judea fought against Rome after the destruction of Jerusalem; what I translated from the German Karlheinz Deschner, or even a book written by a liberal English, like Catherine Nixey’s.

But no: these neochristian Americans, unlike the Europeans mentioned above, make a teenage tantrum with Christian symbols that only denote their inability to reach adulthood.

If a revolutionary man wants to do something against Christianity, adulthood begins by reading, say, Uncle Adolf’s table talks. On this site I still have to collect the remaining of Hitler’s anti-Christian pronouncements in my cited quotations (I am missing another seven citations).

The tragedy I see with these groups who aspire to revolutionaries is that they don’t seem to realise that, given that the ethnosuicide of the West has to do with Semitic psyops, it’s more urgent to imitate Athens than Sparta at the moment; more important to philosophically understand the psyop than to do a military career. Otherwise one ends up playing with unassimilated forms of Christianity either with Satanism (which circumscribes an Abrahamic religion although negatively) or with the Luther hymn.

What kind of ‘anti-Semitic’ revolutionaries are these who cannot encapsulate the virus of Judeo-Christianity in their minds? Why don’t they follow the commandment of the Oracle of Delphi, an Apollonian oracle uncontaminated by Abrahamic religions (cf. my forthcoming translated autobiographical book)?

A Satanist would not scare the educated Christians of the racialist movement in the US. He would only inspire pity, as if he were a mentally ill person, a schizo individual. However, when I discuss with a Christian, as I recently did in Unz Review, he resorts to wanting to psychoanalyse me with my father because the objective information I represent he cannot answer.

Below, excerpts from the final

chapter of Nixey’s book:

‘Moreover, we forbid the teaching of any doctrine by those who labour under the insanity of paganism’.

– Justinian Code

The philosopher Damascius was a brave man: you had to be to see what he had seen and still be a philosopher. But as he walked through the streets of Athens in AD 529 and heard the new laws bellowed out in the town’s crowded squares, even he must have felt the stirrings of unease. He was a man who had known persecution at the hands of the Christians before. He would have been a fool not to recognize the signs that it was beginning again.

As a young man, Damascius had studied philosophy in Alexandria, the city of the murdered Hypatia. He had not been there for long when the city had turned, once again, on its philosophers. The persecution had begun dramatically. A violent attack on a Christian by some non-Christian students had started a chain of reprisals in which philosophers and pagans were targeted. Christian monks, armed with an axe, had raided, searched then demolished a house accused of being a shrine to ‘demonic’ idols. The violence had spread and Christians had found and collected all images of the old gods from across Alexandria, from the bathhouses and from people’s homes. They had placed them in a pyre in the centre of the city and burned them. As the Christian chronicler, Zachariah of Mytilene, comfortably observed, Christ had declared that he had ‘given you the authority to tread on snakes and scorpions, and over all enemy power’.

For Damascius and his fellow philosophers, however, all that had been a mere prelude to what came next. Soon afterwards, an imperial officer had been sent to Alexandria to investigate paganism. The investigation had rapidly turned to persecution. This was when philosophers had been tortured by being hung up by cords and when Damascius’s own brother had been beaten with cudgels – and to Damascius’s great pride, had remained silent…

Damascius decided to flee. In secret, he hurried with his teacher, Isidore, to the harbour and boarded a boat. Their final destination was Greece, and Athens, the most famous city in the history of Western philosophy.

It was now almost four decades since Damascius had escaped to Athens as an intellectual exile. In that time, a lot had changed. When he had arrived in the city he had been a young man; now he was almost seventy. But he was still as energetic as ever, and as he walked about Athens in his distinctive philosopher’s cloak – the same austere cloak that Hypatia had worn – many of the citizens would have recognized him. For this émigré was now not only an established fixture of Athenian philosophy and a prolific author, he was also the successful head of one of the city’s philosophical schools: the Academy. To say ‘one of’ the schools is to diminish this institution’s importance: it was perhaps the most famous school in Athens, indeed in the entire Roman Empire. It traced its history back almost a thousand years and it would leave its linguistic traces on Europe and America for two thousand years to come. Every modern academy, académie and akademie owes its name it.

Since he had crossed the wine-dark sea, life had gone well for Damascius – astonishingly well, given the turbulence he had left behind. In Alexandria, Christian torture, murder and destruction had had its effect on the intellectual life of the city. After Hypatia’s murder the numbers of philosophers in Alexandria and the quality of what was being taught there had, unsurprisingly, declined rapidly. In the writings of Alexandrian authors there is a clear mood of depression, verging on despair. Many, like Damascius, had left.

In fifth-century Athens, the Church was far less powerful and considerably less aggressive. Its intellectuals had felt pressure nonetheless. Pagan philosophers who flagrantly opposed Christianity paid for their dissent. The city was rife with informers and city officials listened to them. One of Damascius’s predecessors had exasperated the authorities so much that he had fled, escaping – narrowly – with his life and his property. Another philosopher so vexed the city’s Christians by his unrepentant ‘pagan’ ways that he had had to go into exile for a year to get away from the ‘vulture-like men’ who now watched over Athens. In an act that could hardly have been more symbolic of their intellectual intentions, the Christians had built a basilica in the middle of what had once been a library. The Athens that had been so quarrelsome, so gloriously and unrepentantly argumentative, was being silenced. This was an increasingly tense, strained world. It was, as another author and friend of Damascius put it, ‘a time of tyranny and crisis’.

The very fabric of the city had changed. Its pagan festivals had been stopped, its temples closed and, as in Alexandria, the skyline of the city had been desecrated; here, by the removal of Phidias’s great figure of Athena…

Despite his success, Damascius had not forgotten what he had seen in Alexandria – and had not forgiven it, either. His writings show a never-failing contempt for the Christians. He had seen the power of Christian zeal in action. His brother had been tortured by it. His teacher had been exiled by it. And, in the year 529, zealotry was once again in evidence. Christianity had long ago announced that all pagans had been wiped out. Now, finally, reality was to be forced to fall in with the triumphant rhetoric.

The determination that lay behind this threat was not only felt in Athens in this period. It was in AD 529, the very same year in which the atmosphere in Athens began to worsen, that St Benedict destroyed that shrine to Apollo in Monte Cassino…

Previous attacks on Damascius and his scholars had largely been driven by local enthusiasms; a violently aggressive band of Alexandrian monks here, an officious local official there. But this attack was something new. It came not from the enthusiasm of a hostile local power; it came in the form of a law – from the emperor himself…

This was the end. The ‘impious and wicked pagans’ were to be allowed to continue in their ‘insane error’ no longer. Anyone who refused salvation in the next life would, from now on, be all but damned in this one…

This was no longer mere prohibition of other religious practices. It was the active enforcement of Christianity on every single, sinful pagan in the empire. The roads to error were being closed, forcefully. Everyone now had to become Christian. Every single person in the empire who had not yet been baptized now had to come forward immediately, go to the holy churches and ‘entirely abandon the former error [and] receive saving baptism’…

‘Moreover’, it reads, ‘we forbid the teaching of any doctrine by those who labour under the insanity of paganism’ so that they might not ‘corrupt the souls of their disciples.’ The law goes on, adding a finicky detail or two about pay, but largely that is it.

Its consequences were formidable. It was this law that forced Damascius and his followers to leave Athens. It was this law that caused the Academy to close. It was this law that led the English scholar Edward Gibbon to declare that the entirety of the barbarian invasions had been less damaging to Athenian philosophy than Christianity was. This law’s consequences were described more simply by later historians. It was from this moment, they said, that a Dark Age began to descend upon Europe…

Free philosophy has gone. The great destruction of classical texts gathers pace. The writings of the Greeks ‘have all perished and are obliterated’: that was what John Chrysostom had said. He hadn’t been quite right, then: but time would bring greater truth to his boast. Undefended by pagan philosophers or institutions, and disliked by many of the monks who were copying them out, these texts start to disappear. Monasteries start to erase the works of Aristotle, Cicero, Seneca and Archimedes. ‘Heretical’ – and brilliant – ideas crumble into dust. Pliny is scraped from the page. Cicero and Seneca are overwritten. Archimedes is covered over. Every single work of Democritus and his heretical ‘atomism’ vanishes. Ninety per cent of all classical literature fades away…

The pages of history go silent. But the stones of Athens provide a small coda to the story of the seven philosophers… The lovely statue of Athena, the goddess of wisdom, suffered as badly as the statue of Athena in Palmyra had. Not only was she beheaded she was then, a final humiliation, placed face down in the corner of a courtyard to be used as a step. Over the coming years, her back would be worn away as the goddess of wisdom was ground down by generations of Christian feet.

The ‘triumph’ of Christianity was complete.

The supremacy over Athens

At this point, we must address the issue that will certainly be around the heads of many readers: the comparison Sparta-Athens. What city was better?

Often we are told that Athens represented the artistic and spiritual summit of Greece and Sparta the physical and warrior evolution. It’s not as easy as that. We must start from the basis that it is a great mistake to judge the development of a society for its commercial or material advancement. This would lead us to conclude that the illiterate Charlemagne was lower than anybody else present, or Dubai the home of the world’s most exalted civilisation…

Thus we come to the important subject of art. It usually happens that it is a common argument to vilify Sparta. The Spartans used to say that they carved monuments in the flesh, which implied that their art was a living one: literally them, and the individuals that composed their homeland.

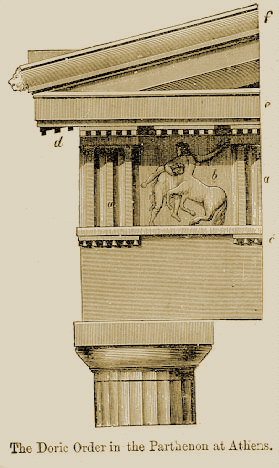

But Sparta also had conventional art as understood in the present. It was famous throughout Greece for its music and dance (of which nothing has survived), as well as its highly prised poetry that has come to us fragmented. Its architects and sculptors were employed in such prestigious places as Delphi and Olympia, and imposed a stamp of straight simplicity and crystal clarity in their works.

The best example of this is the sober Doric style, a direct heritage of Sparta that became a model not only for countless temples throughout Greece, as the Parthenon in Athens itself, but also for the classic taste of later Europe that has endeavoured to continue the legacy of Greece and Rome.

The best example of this is the sober Doric style, a direct heritage of Sparta that became a model not only for countless temples throughout Greece, as the Parthenon in Athens itself, but also for the classic taste of later Europe that has endeavoured to continue the legacy of Greece and Rome.

(Passages from one of Evropa Soberana’s essays in The Fair Race’s Darkest Hour.)

Julian, 57

Julian Augustus

Those marvellous days in Athens came to an abrupt end when an imperial messenger arrived with orders that I attend Constantius at Milan. No reason was given. I assumed that I was to be executed. Just such a message had been delivered to Gallus. I confess now to a moment of weakness. Walking alone in the agora, I considered flight. Should I disappear in the back streets of Athens? Change my name? Shave my head? Or should I take to the road like a New Cynic and walk to Pergamon or Nicomedia and lose myself among students, hide until I was forgotten, assumed dead, no longer dangerous?

Suddenly I opened my arms to Athena. I looked up to her statue on the acropolis, much to the astonishment of the passers-by (this took place in front of the Library of Pantainos).

I prayed that I be allowed to remain in Athena’s city, preferring death on the spot to departure. But the goddess did not answer. Sadly I dropped my arms. Just at that moment, Gregory emerged from the library and approached me with his wolf’s grin.

“You’re leaving us,” he said. There are no secrets in Athens. I told him that I was reluctant to go but the Emperor’s will must be done.

“You’ll be back,” he said, taking my arm familiarly.

“I hope so.”

“And you’ll be the Caesar then, a man of state, with a diadem and guards and courtiers! It will be interesting to see just how our Julian changes when he is set over us like a god.”

“I shall be the same,” I promised, sure of death.

“Remember old friends in your hour of greatness.” A scroll hidden in Gregory’s belt dropped to the pavement. Blushing, he picked it up.

“I have a special permit,” he stammered. “I can withdraw books, certain books, approved books…”

I laughed at his embarrassment. He knew that I knew that the Pantainos Library never allows any book to be taken from the reading room. I said I would tell no one.

The proconsul treated me decently. He was a good man, but frightened. I recognized at once in his face the look of the official who does not know if one is about to be executed or raised to the throne. It must be cruelly perplexing for such men. If they are kind, they are then vulnerable to a later charge of conspiracy; if they are harsh, they may live to find their victim great and vindictive. The proconsul steered a middle course; he was correct; he was conscientious; he arranged for my departure the next morning.

My last evening in Athens is still too painful to describe. I spent it with Macrina. I vowed to return if I could. Next day, at first light, I left the city. I did not trust myself to look back at Athena’s temple floating in air, or at the sun-struck violet line of Hymettos. Eyes to the east and the morning sun, I made the sad journey to Piraeus and the sea.

Julian, 45

Julian presiding at a conference of Sectarians

(Edward Armitage, 1875)

Just inside the wall of the city, I left my driver. Then like one who has gone to sleep over a book of history, I stepped into the past. I stood now on that ancient highway—known simply as The Road—which leads from gate to agora to acropolis beyond. I was now in history. In the present I was part of the past and, simultaneously, part of what is to come. Time opened his arms to me and in his serene embrace I saw the matter whole: a circle without beginning or end.

To the left of the gate was a fountain in which I washed the dust from my face and beard. Then I proceeded along The Road to the agora. I am told that Rome is infinitely more impressive than Athens. I don’t know. I have never visited Rome. But I do know that Athens looks the way a city ought to look but seldom does. It is even better planned than Pergamon, at least at its centre. Porticoes gleam in the bright sun. The intense blue sky sets off the red tile roofs and makes the faded paint of columns seem to glow.

The Athenian agora is a large rectangular area enclosed by long porticoes of great antiquity. The one on the right is dedicated to Zeus; the one on the left is of more recent date, the gift of a young king of Pergamon who studied here. In the centre of the agora is the tall building of the University, first built by Agrippa in the time of Augustus. The original building—used as a music hall—collapsed mysteriously in the last century. I find the architecture pretentious, even in its present somewhat de-Romanized version. But pretentious or not, this building was my centre in Athens. For here the most distinguished philosophers lecture. Here I listened three times weekly to the great Prohaeresius, of whom more later.

Behind the University are two porticoes parallel to one another, the last being at the foot of the acropolis. To one’s right, on a hill above the agora, is a small temple to Hephaestos surrounded by gardens gone to seed. Below this hill are the administrative buildings of Athens, the Archives, the Round House where the fifty governors of Athens meet—this last is a peculiar-looking structure with a steep roof which the Athenians, who give everything and everyone a nickname, call “the umbrella”. There used to be many silver statues in the Round House but the Goths stole them in the last century.

Few people were abroad as the sun rose to noon. A faint breeze stirred the dust on the old pitted paving. Several important-looking men, togas draped ineptly about plump bodies, hurried towards the Bouletrion. They had the self-absorbed air of politicians everywhere. Yet these men were the political heirs of Pericles and Demosthenes. I tried to remember that as I watched them hurry about their business.

Then I stepped into the cool shade of the Painted Portico. For an instant my eyes were dazzled, the result of sudden dimness. Not for some time was I able to make out the famous painting of the Battle of Marathon which covers the entire long wall of the portico. But as my eyes grew used to the shade, I saw that the painting was indeed the marvel the world says it is. One can follow the battle’s course by walking the length of the portico. Above the painting hang the round shields of the Persians, captured that day. The shields have been covered with pitch to preserve them.

Looking at those relics of a battle fought eight hundred years before, I was much moved. Those young men and their slaves—yes, for the first time in history slaves fought beside their masters—together saved the world. More important, they fought of their own free will, unlike our soldiers, who are either conscripts or mercenaries. Even in times of peril, our people will not fight to protect their country. Money, not honour, is now the source of Roman power. When the money goes, the state will go. That is why Hellenism must be restored, to instil again in man that sense of his own worth which made civilization possible, and won the day at Marathon.

Julian, 43

Julian presiding at a conference of Sectarians

(Edward Armitage, 1875)

Athens. It has been eight years since I rode up to the city gate in a market cart, an anonymous student who gaped at the sights like any German come to town. My first glimpse of the acropolis was startling and splendid. It hovers over the city as though held in the hand of Zeus, who seems to say: “Look, children, at how your gods live!” Sunlight flashes off the metal shield of the colossal statue of Athena, guarding her city. Off to the left I recognized the steep pyramidal mountain of Lykabettos, a great pyramid of rock hurled to earth by Athena herself; to this day wolves dwell at its foot.

The driver turned abruptly into a new road. I nearly fell out of the cart. “Academy Road,” he announced in the perfunctory loud voice of one used to talking to foreigners. I was impressed. The road from Athens to the Academy’s grove is lined with ancient trees. It begins at the city’s Dipylon Gate—which was straight ahead of us—and crosses through suburbs to the green-leafed academy of Aristotle.

The Dipylon Gate was as busy in the early morning as any other great city’s gate might have been at noon. It is a double gate, as its name indicates, with two tall towers on the outside. Guards lolled in front, paying no attention to the carts and pedestrians who came and went.

As we passed through the outer gate, our cart was suddenly surrounded by whores. Twenty or thirty women and girls of all ages rushed out of the shadows of the wall. They fought with one another to get close to the cart. They tugged at my cloak. They called me “Billy Goat”, “Pan”, “Satyr”, and other less endearing terms. With the skill of an acrobat one pretty child of fourteen vaulted the railing of my cart and firmly grasped my beard in her fist. The soldiers laughed at my discomfort.

With some effort I pried my beard free from her fingers, but not before her other hand had reached between my legs, to the delight of those watching. But the driver was expert at handling these girls. With a delicate flick of his whip, he snapped at her hand. It was withdrawn with a cry. She leapt to the ground.

The other women jeered us. Their curses were vivid and splendid, Homeric! Then as we passed through the second gate they turned back, for a troop of cavalry had appeared at the outer gate. Like bees swarming in a garden, they surrounded the soldiers.

I arranged my tunic. The sharp tug of the girl’s hand had had its effect upon me, and against my will I thought of love-making and wondered where the best girls in Athens might be found. I was not then, as I am now, celibate. Yet even in those days I believed that it was virtuous to mortify the flesh, for it is a fact that continence increases intellectual clarity.

But I was also twenty-three years old and the flesh made demands on me in a way that the mind could not control. Youth is the body’s time. Not a day passed in those years that I did not experience lust. Not a week passed that I did not assuage that lust. But I do not agree with those Dionysians who maintain that the sexual act draws men closer to the One God. If anything, it takes a man away from God, for in the act he is blind and thoughtless, no more than an animal engaged in the ceremony of creation.

Yet to each stage of one’s life certain things are suitable and for a few weeks, eight years ago, I was young, and knew many girls. Even now on this hot Asiatic night, I recall with unease that brilliant time, and think of love-making. I notice that my secretary is blushing. Yet he is Greek!

In chapter seven of The Darkening Age: The Christian

Destruction of the Classical World, Catherine Nixey wrote:

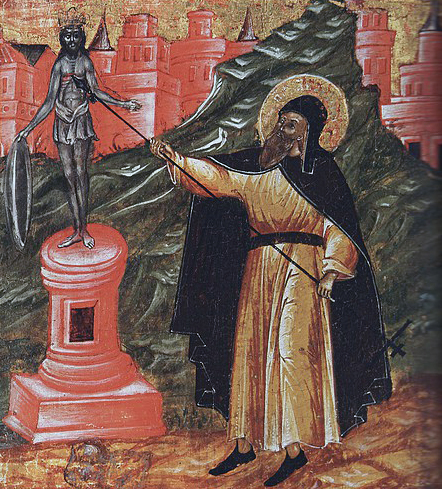

Constantine… demanded that the statues be taken from the temples. Christian officials, so it was said, travelled the empire, ordering the priests of the old religion to bring their statues out of the temples. From the 330s onwards some of the most sacred objects in the empire started to be removed. It is hard, today, to understand the enormity of Constantine’s order. If Michelangelo’s Pietà were taken from the Vatican and sold, it would be considered a terrible act of cultural vandalism—but it wouldn’t be sacrilege as the statue is not in itself sacred. Statues in Roman temples were. To remove them was a gross violation, and Constantine knew it…

The possibility that Jesus would triumph over all other gods would, at the time, have seemed almost preposterous. Constantine was faced with an intransigent population who insisted on worshipping idols at the expense of the risen Lord. He realized that conversion would be more ‘easily accomplished if he could get them to despise their temples and the images contained therein’. And what better way to teach wayward pagans the vanity of their gods than by cracking open their statues and showing that they were, quite literally, empty? Moreover, a religious system in which sacrifice was central would struggle to survive if there was nothing to sacrifice to. There was good biblical precedent for his actions. In Deuteronomy, God had commanded that His chosen people should overthrow altars, burn sacred groves and hew down the graven images of the gods. If Constantine attacked the temples then he was not being a vandal. He was doing God’s good work.

And so it began. The great Roman and Greek temples were— or so Eusebius said—broken open and their statues brought out, then mutilated…

Not all the temple statues were melted down. The ‘tyrant’ Constantine also had an eye for art and many objects were shipped back as prize baubles for the emperor’s new city, Constantinople (Constantine, like Alexander the Great, was not one for self-effacement). The Pythian Apollo was put up as ‘a contemptible spectacle’ in one square; the sacred tripods of Delphi turned up in Constantinople’s hippodrome, while the Muses of Helicon found themselves relocated to Constantine’s palace. The capital looked wonderful. The temples looked—were—desecrated. As his biographer wrote with satisfaction, Constantine ‘confuted the superstitious error of the heathen in all sorts of ways’.

And yet despite the horror of what Constantine was asking his subjects to do there was little resistance…

Christianity could have been tolerant: it was not preordained that it would take this path. There were Christians who voiced hopes for tolerance, even ecumenicalism. But those hopes were dashed. For those who wish to be intolerant, monotheism provides very powerful weapons. There was ample biblical justification for the persecution of non-believers.

The Bible, as a generation of Christian authors declared, is very clear on the matter of idolatry. As the Christian author Firmicus Maternus reminded his rulers—perfectly correctly—there lay upon emperors an ‘imperative necessity to castigate and punish this evil’. Their ‘severity should be visited in every way on the crime’. And what precisely did God advise as a punishment for idolatry? Deuteronomy was clear: a person indulging in this should be stoned to death. And if an entire city fell into such sin? Again, the answer was clear: ‘destruction is decreed’.

The desecration continued for centuries. In the fifth century AD, the colossal statue of Athena, the sacred centrepiece of the Acropolis in Athens, and one of the most famous works of art in the empire, was torn down from where she had stood guard for almost a thousand years, and shipped off to Constantinople—a great coup for the Christian city and a great insult to the ‘pagans’…

Note of the Ed.: After the centuries, Europeans even forgot how the Greco-Roman sculptures that were destroyed looked like. My guess is that Constantine’s bishops were not Aryans. Destroying a representation of the beauty of the Aryan physique was part of the Semitic takeover of white society: Let’s destroy your self-image as a means to undermine your self-esteem. Something similar is happening today with the religion of Holocaustianity: Let’s undermine your self-image from a decent person to historic grievances so that you may accept masses of non-white immigrants.

Note of the Ed.: After the centuries, Europeans even forgot how the Greco-Roman sculptures that were destroyed looked like. My guess is that Constantine’s bishops were not Aryans. Destroying a representation of the beauty of the Aryan physique was part of the Semitic takeover of white society: Let’s destroy your self-image as a means to undermine your self-esteem. Something similar is happening today with the religion of Holocaustianity: Let’s undermine your self-image from a decent person to historic grievances so that you may accept masses of non-white immigrants.

History is written by the winners and the Christian victory was absolute. The Church dominated European thought for more than a millennium. Until 1871 the University of Oxford required that all students were members of the Church of England, while in most cases to be given a fellowship in an Oxford college one had to be ordained. Cambridge was a little freer—but not much.

This was not an atmosphere conducive to criticism of Christianity and indeed, in English histories, there was little. For centuries, the vast majority of historians unquestioningly took up the Christian cause and routinely and derogatorily referred to non-Christians as ‘pagans’, ‘heathens ‘ and ‘idolaters’. The practices and sufferings of these ‘pagans’ were routinely belittled, trivialized or—more often—entirely ignored. As one modern scholar has observed: ‘The story of early Christian history has been told almost wholly on the basis of Christian sources.’

Yesterday I said that in the third volume of the series Christianity’s Criminal History, ‘The Ancient Church: Forgery, Brainwashing, Exploitation, Annihilation’, Deschner argues that the tales of Christian martyrs in early Christianity were grossly exaggerated, and that I planned in the future to translate some passages of it. But the impatient English reader can go to his nearest library and read chapter four of Catherine Nixey’s recently published The Darkening Age, ‘On the Small Number of Martyrs’.

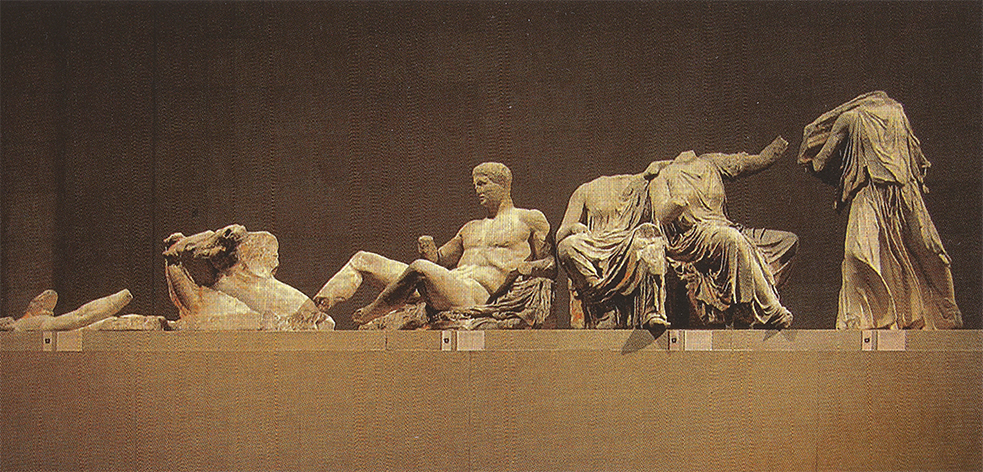

Within that chapter are included the images in colour that illustrate the book. Above, you can see the surviving figures of the Parthenon in Athens. Nixey says that these figures ‘were almost certainly mutilated by Christians who believed them to be “demonic”. The central figures of the group are missing, probably levered off the ground into rubble to build a Christian church’ (image facing page 57).

‘That all superstition of pagans and heathens should be annihilated is what God wants, God commands, God proclaims.’

— St Augustine

This was no time for a philosopher to be philosophical. ‘The tyrant’, as the philosophers put it, was in charge and had many alarming habits. In Damascius’s own time, houses were entered and searched for books and objects deemed unacceptable. If any were found they would be removed and burned in triumphant bonfires in town squares. Discussion of religious matters in public had been branded a ‘damnable audacity’ and forbidden by law. Anyone who made sacrifices to the old gods could, the law said, be executed. Across the empire, ancient and beautiful temples had been attacked, their roofs stripped, their treasures melted down, their statues smashed. To ensure that their rules were kept, the government started to employ spies, officials and informers to report back on what went on in the streets and marketplaces of cities and behind closed doors in private homes. As one influential Christian speaker put it, his congregation should hunt down sinners and drive them into the way of salvation as relentlessly as a hunter pursues his prey into nets.

The consequences of deviation from the rules could be severe and philosophy had become a dangerous pursuit. Damascius’s own brother had been arrested and tortured to make him reveal the names of other philosophers, but had, as Damascius recorded with pride, ‘received in silence and with fortitude the many blows of the rod that landed on his back’. Others in Damascius’ s circle of philosophers had been tortured; hung up by the wrists until they gave away the names of their fellow scholars. A fellow philosopher had, some years before, been flayed alive. Another had been beaten before a judge until the blood flowed down his back.

The savage ‘tyrant’ was Christianity. From almost the very first years that a Christian emperor had ruled in Rome in AD 312, liberties had begun to be eroded. And then, in AD 529, a final blow had fallen. It was decreed that all those who laboured ‘under the insanity of paganism’—in other words Damascius and his fellow philosophers—would be no longer allowed to teach. There was worse. It was also announced that anyone who had not yet been baptized was to come forward and make themselves known at the ‘holy churches’ immediately, or face exile. And if anyone allowed themselves to be baptized, then slipped back into their old pagan ways, they would be executed.

For Damascius and his fellow philosophers, this was the end. They could not worship their old gods. They could not earn any money. Above all, they could not now teach philosophy. The Academy, the greatest and most famous school in the ancient world—perhaps ever—a school that could trace its history back almost a millennium, closed.

It is impossible to imagine how painful the journey through Athens would have been. As they went, they would have walked through the same streets and squares where their heroes—Socrates, Plato, Aristotle—had once walked and worked and argued. They would have seen in them a thousand reminders that those celebrated times were gone. The temples of Athens were closed and crumbling and many of the brilliant statues that had once stood in them had been defaced or removed. Even the Acropolis had not escaped: its great statue of Athena had been torn down.

Little of what is covered by this book is well-known outside academic circles. Certainly it was not well-known by me when I grew up in Wales, the daughter of a former nun and a former monk. My childhood was, as you might expect, a fairly religious one. We went to church every Sunday; said grace before meals, and I said my prayers (or at any rate the list of requests which I considered to be the same thing) every night. When Catholic relatives arrived we play-acted not films but First Holy Communion and, at times, even actual communion…

As children, both had been taught by monks and nuns; and as a monk and a nun they had both taught. They believed as an article of faith that the Church that had enlightened their minds was what had enlightened, in distant history, the whole of Europe. It was the Church, they told me, that had kept alive the Latin and Greek of the classical world in the benighted Middle Ages, until it could be picked up again by the wider world in the Renaissance. And, in a way, my parents were right to believe this, for it is true. Monasteries did preserve a lot of classical knowledge.

But it is far from the whole truth. In fact, this appealing narrative has almost entirely obscured an earlier, less glorious story. For before it preserved, the Church destroyed.

In a spasm of destruction never seen before—and one that appalled many non-Christians watching it—during the fourth and fifth centuries, the Christian Church demolished, vandalized and melted down a simply staggering quantity of art. Classical statues were knocked from their plinths, defaced, defiled and torn limb from limb. Temples were razed to their foundations and burned to the ground. A temple widely considered to be the most magnificent in the entire empire was levelled.

Many of the Parthenon sculptures were attacked, faces were mutilated, hands and limbs were hacked off and gods were decapitated. Some of the finest statues on the whole building were almost certainly smashed off then ground into rubble that was then used to build churches.

Books—which were often stored in temples—suffered terribly. The remains of the greatest library in the ancient world, a library that had once held perhaps 700,000 volumes, were destroyed in this way by Christians. It was over a millennium before any other library would even come close to its holdings. Works by censured philosophers were forbidden and bonfires blazed across the empire as outlawed books went up in flames.

Fragment of a 5th-century scroll

showing the destruction of the Serapeum

by Pope Theophilus of Alexandria

The work of Democritus, one of the greatest Greek philosophers and the father of atomic theory, was entirely lost. Only one per cent of Latin literature survived the centuries. Ninety-nine per cent was lost.

The violent assaults of this period were not the preserve of cranks and eccentrics. Attacks against the monuments of the ‘mad’, ‘damnable’ and ‘insane’ pagans were encouraged and led by men at the very heart of the Catholic Church. The great St Augustine himself declared to a congregation in Carthage that ‘that all superstition of pagans and heathens should be annihilated is what God wants, God commands, God proclaims!’ St Martin, still one of the most popular French saints, rampaged across the Gaulish countryside levelling temples and dismaying locals as he went. In Egypt, St Theophilus razed one of the most beautiful buildings in the ancient world. In Italy, St Benedict overturned a shrine to Apollo. In Syria, ruthless bands of monks terrorized the countryside, smashing down statues and tearing the roofs from temples.

St John Chrysostom encouraged his congregations to spy on each other. Fervent Christians went into people’s houses and searched for books, statues and paintings that were considered demonic. This kind of obsessive attention was not cruelty. On the contrary: to restrain, to attack, to compel, even to beat a sinner was— if you turned them back to the path of righteousness—to save them. As Augustine, the master of the pious paradox put it: ‘Oh, merciful savagery.’

The results of all of this were shocking and, to non-Christians, terrifying. Townspeople rushed to watch as internationally famous temples were destroyed. Intellectuals looked on in despair as volumes of supposedly unchristian books—often in reality texts on the liberal arts—went up in flames. Art lovers watched in horror as some of the greatest sculptures in the ancient world were smashed by people too stupid to appreciate them—and certainly too stupid to recreate them.

Since then, and as I write, the Syrian civil war has left parts of Syria under the control of a new Islamic caliphate. In 2014, within certain areas of Syria, music was banned and books were burned. The British Foreign Office advised against all travel to the north of the Sinai Peninsula. In 2015, Islamic State militants started bulldozing the ancient Assyrian city of Nimrud, just south of Mosul in Iraq because it was ‘idolatrous’. Images went around the world showing Islamic militants toppling statues around three millennia old from their plinths, then taking hammers to them. ‘False idols’ must be destroyed. In Palmyra, the remnants of the great statue of Athena that had been carefully repaired by archaeologists, was attacked yet again. Once again, Athena was beheaded; once again, her arm was sheared off.

I have chosen Palmyra as a beginning, as it was in the east of the empire, in the mid-380s, that sporadic violence against the old gods and their temples escalated into something far more serious. But equally I could have chosen an attack on an earlier temple, or a later one. That is why it is a beginning, not the beginning. I have chosen Athens in the years around AD 529 as an ending—but again, I could equally have chosen a city further east whose inhabitants, when they failed to convert to Christianity, were massacred and their arms and legs cut off and strung up in the streets as a warning to others.