Book 2

Chapter Two

Though I hoped I would have learned from these incidents, I am afraid to say that (to my mind) I had cause to fight with my father a third time in these cold, desperate weeks. My father does not learn or change. Of all the incidents, it was the most severe. It lingers with me even today in a mind that has by now forgotten most of my childhood and adolescent pain, blotting it out over long years of blood and agonising tears, if only for survival, and to the point that most of my anecdotes are hard to recall, and require concentrated thought to recount, even when the vague circumstances of them are still intrusive enough psychologically, and as if on the tip of my tongue.

I was in the car with my mother and father this time, being driven back from Chelmsford one Saturday afternoon, where we had attended the shopping centre. Due to my leg length, I sat in the front seat of the family Škoda and my mother in the rear on the right, behind Dad’s seat. My friend Ami was in the back seat behind me, and Dad was talking with her at the time, discussing her troubles. For once, he seemed empathetic in a manner that he would never have been with me if I had mentioned my own misery to him.

“So why do you think your own life isn’t going well, Ami? What’s getting you down?” my father said, asking her about her problems openly and in a warm manner that disguised the forwardness of his statement. She had been in his company a few times before, but he did not know my friend well, bar to know that we had both been in Brookside together. Ami had now moved back to her parents’ home in Loughton.

“Well, Billy,” she replied, more openly than I would ever have been able to, having been given a chance I never had to open up already in the hospital, and thus perhaps more used to intimate life discussions, talking to him as matter-of-factly as to a familiar therapist, lines that she had said out loud many times before, “I’m afraid I’ve had problems since I was a child. My mother was an alcoholic, and my father didn’t deal well with this. Aside from that, I was raped when I was younger. It shattered me. I’ve got OCD now, and Depression, as well as Dissociative Identity Disorder. I share my head with a woman named Anna and a couple of other people, and she talks to me with them, and in my own voice at times, too.”

Dad gasped a little and then nodded understandingly. Unused to psychiatric ideas as I knew he was, I was taken aback by his patience, as if Ami had announced the most normal and straightforward thing in the world. Embarrassing to my conscience, a brief stab of jealousy shot through me as I realised then that if I had said something similar, Dad would have scoffed as he always did or given me a quizzical look. Then, a sudden irritation entered his tone, bordering on great anger, “That’s awful, Ami. Who was it? Who did this to you? Tell me his name; I’ll kill him! I’ll kill him!”

Dad continued his gesture of rage all the rest of the way down the road until we reached the front door of number 44. The vengeful promise on his part seemed genuine and unforced. I sympathised with Ami very much, already aware of her life circumstances and to far greater detail, but I was silently annoyed at my father by then, and very much. He would never have responded the same way had it been me reporting to him. Later that day, this thought was pressing on my mind, so I mentioned it to Ami, hoping she would not take my worries as an offence. Thankfully, she seemed to understand me and said, in a small yet supportive voice, “Ben, I know what you mean. I’m really sorry to hear. To be honest, please don’t get upset, but I think your Dad is a real arsehole to you… so many times I’ve seen him picking on you, and he speaks to you like total sh*t…”

A great tide of emotion welled up in me then. I thanked Ami profusely for what she had said. It was the first time someone had ever mentioned Dad’s long conduct towards me openly. Then she said, “It’s probably because he doesn’t know what happened to you; perhaps you should tell him. I know it’s hard, but when I told my father, it helped me a lot, and then I found I could open up to Mel and the rest of the unit staff back at Brookside… tell him in your own time. But definitely open up. At the moment, he’s cold and rude towards you because he doesn’t understand.” I nodded. It seemed she was right.

In the evening, Dad was kind enough to drive Ami back to Loughton and drop her off at her father’s luxury property. Saying my goodbyes to her on the front step of our house as I was exhausted from the day, I lingered at home nervously, waiting for him to return. My mother was still in the kitchen, preparing his evening meal. She didn’t know what I had in mind. She was busying about out of my way as I sat on the futon in my room preparing myself, unsure of his response but having taken what Ami said seriously and knowing it would help me, in the long run, to have this chat with him about my abuse, and as soon as possible.

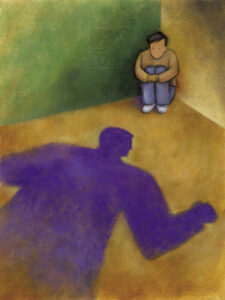

Just under an hour and a half later, Dad returned to our house. From my corner bedroom, I heard the familiar sound of his engine pulling up and switching off, the car door slamming as it always did, and then him hurrying up the steps and the key in the front door. He was panting a little as he entered the house. I gave him a chance to get his breath back, but then, perhaps too soon, excited from all the thoughts welling up in my mind, I went over to him as he was again sat in his chair in the corner, waiting for his dinner to arrive, having been in the house about twenty minutes, and stood beside him on the new laminated wood-effect floor, and in a quiet, polite voice said: “hello Dad, can I have a word with you please?”

His voice was harsher than I expected and snappy, replying, “What? What is it? Can’t you wait? I’m tired tonight”, to which I replied, “I’m sorry, Dad, but it’s important, do you mind if I speak to you?” and heard him say again, in peeved agitation, “OK. What then? Come on. Get it over with!”, words which did nothing for my confidence. But I went on, plucking up all my courage, “Dad, I wanted to tell you about Tariq.” “Well, what about him?” “He abused me, Dad. When I was at school at the Prep school, he beat me up a lot, and then he touched me, and tried to have sex with me, and did other things…”

I was tailing off, not knowing how to continue. My father was still glaring up at me, motionless, not providing a very comfortable atmosphere at all. Instead of surprise, or supportive words, like those he had offered Ami, all he said to me was, “Look Benjamin, I’m very tired tonight. Can this not wait till some other time? I haven’t been in long, and I want to have my tea.”

He got up out of his chair and went out of the room, blundering down the unlit hall to the toilet to freshen up. I was in shock. More than this, I was very hurt. I followed him, still trying impotently to speak in his ear. “Dad, listen to me; this is important! Tariq hurt me! Tariq hurt me very much! Listen to me, Dad!” but all my father could say, distractedly over his shoulder, was, “Look, leave it now. I’m tired, and I need to get ready for tea. Stop getting yourself in a state.” I was heartbroken then, but there was nothing I could do. Clearly, he did not want to listen to me and was not taking me seriously. Anger erupted in me again, a great, huge, coruscating anger.

As he left the bathroom, I thrust my hand out and pushed my father until he stumbled, his body almost falling over, stopped only by bashing into the wall of the hall. He stopped for a second, in shock of his own, not knowing what had happened, and then turned on me with a yell and grabbed out at me. I, too, was snarling at this point, and again, we grappled on the floor, me squeezing his wrists and him trying to subdue me and knock me to the floor. More and more I squeezed, as I called out, in broken, incandescent rage, “Believe me! Believe me! You c**t, you f**king c**t! I hate you! Believe me!” and he ignored my impassioned voice, unclear than I was hurt more than just ‘behaving badly’, and instead managed to free one of my hands from his right arm, giving a little gasp as I squeezed my hardest, trying to cause him pain.

In a second, his right arm free, he screwed up his fist and punched me full-on in the face, his knuckles landing on the bridge of my nose, snapping the soft tissue of the tip to the side with a horrifying crunch as blood started to trickle in a painful nosebleed. I screeched at that point in fear, surprise, and pain and dropped my other hand also, going to cradle my nose, trying my hardest to slide my busted nasal cartilage back into place, in sharp, terrible pain, stinging ferociously, and with the cold, choking drip of blood. Using this opportunity, he stepped backwards and moved back into the light of the living room away from me. But anger was upon me, and I did not stall for long.

Despite my broken nose, I howled as I powered into my bedroom, barrelling over to the shelf to pick up the grip of my spring-powered BB pistol, making sure the magazine was full and slid into place. Then, taking the weapon in my right hand, I charged back into the hall as my Dad had just entered the living room, going across to talk to my mother, who was by now in a fluster, asking him, “What is it? What’s happened?” to which Dad replied, “Get this f**king maniac away from me!” and, on hearing this, I exploded, and shouted, “don’t call me a f**king maniac! You attacked me, you c**t, you f**king bast*rd!” and, to my mother’s horrified gasp, hoisted my arm, and pointed the gun at my father, aiming for in between his shoulder blades.

In a split second, grabbing his key, he pushed past me, knocking my barrel to the side, and fled out into the hallway again, and from there, through the front door and off down the steps around the corner of The Shrubberies and away down Chequers Road, with me following hot in pursuit, screaming my hatred at him, and taking time to stop, aim, and discharge the BB gun at him, aiming close, but making sure always to miss by a little, in ferocious anger, but still held back by something, knowing what the impacts of the weapon felt like from having been shot at with it by Tariq previously, and not wishing similar on my father as much as to frighten him, and ‘teach him a lesson’.

Soon, about halfway down to the Chequers Pub on the corner, I broke off my pursuit and turned back to the house, blood pouring down my face, and went up the steps into the toilet just to the left of the front door and, fetching as much toilet paper as I could unwind, stuffed it around my face and held it there, feeling that ultra-sensitive sting once more, and the first bruising around my right eye.

Not much later, as I was still in the toilet, I heard Dad’s feet on the steps and the door swinging back once again as he re-entered our home. There was silence in the hallway, and he did not call for me or attempt to open the door, though he would have known I was there. Instead, he brushed through into the living room to speak to my mother. Distracted and with my ears ringing, perhaps from his blow, I do not know what words passed between them, but I did not emerge for a long time, and I know they talked in my absence.

When I did step out of the downstairs toilet, I was no longer so angry. I dumped the BB gun back in my room. Then, tentatively, I peeked around the corner to the living room and saw Dad sitting back in his familiar chair. He was eating the dinner Mum had prepared for him as if nothing had happened. There was silence as I entered the room. Then I spoke, my voice affected by the stiffness and pain in my face. “I’m sorry I shot at you, Dad. And I’m sorry I fought too. I didn’t mean to hurt you.”

Tears were forming in my bruising eyes. Dad got up out of the chair slowly. I winced a little, but then he spoke, “That’s ok, son. We know you’re not well.” And, tired of warring with him then, I went to him, my head down again, in clinging sadness, ashamed of myself, and put out my hands in a hug, and, for the first time in my life, my father reciprocated and came to me. I felt him put his big, bony arms around me and then the press of my upper chest beneath his red pullover, and so we hugged, there on the floor, in front of my silent mother. “Thanks, Dad,” I said. “I love you”, and he replied, “And you too, son” Then, exhausted and overcome, and not really knowing what to think, I filed quietly back into my room, my broken nose still unaddressed, though spotted by my mother.

In time, my nose healed, although even these days, it has never re-set fully and still hangs off to the side slightly, lending the centre of my face a disquieting asymmetry, the subtle scar tissue bulky just beneath the bridge, and regularly, I experience slight breathing difficulties and prolonged sinus infections.

______ 卐 ______

If this, at ultimate conclusion—the 4 words—(the 14 words is a given) is not why they’re fighting as the final beautiful goal, why are they fighting at all? —Benjamin’s email to the Editor.