I want to expand on what I discussed yesterday with Benjamin about the trauma model of mental disorders because the topic is a universal taboo, including in the racialist community, to the point that catastrophes like those of William Pierce and Don Black’s children are incomprehensible. (My working hypothesis is that, had they been treated well as children, they would have followed in their parents’ footsteps instead of betraying their ideals.)

It all has to do with the omnipresent taboo, and I’d like to illustrate it with the first reading I ever did of a mental health professional who, unlike bio-reductionist psychiatry, which is pseudoscientific, was one of the pioneers in talking about parents who schizophrenized their children.

Theodore Lidz

It was 1983 when I was broke precisely because of the abuse I had suffered at home the previous decade. At the famous Gandhi Bookstore in Mexico City, I read the interview with Dr Theodore Lidz in the book Laing and Anti-Psychiatry, edited by Robert Boyers and Robert Orrill. Back then, there were no comfortable armchairs like those found in Barnes & Noble bookstores, and I had to read that long interview standing up because the subject fascinated me. It was the first time in my life I had read someone who came close to what I believed had happened in my family.

Seven years later, I managed to buy a copy of Boyers and Orrill’s book, translated into Spanish by Alianza Editorial of Madrid, which was the same edition I had read at the Gandhi Bookstore. Since I don’t have the original English version, I can’t quote a passage from the interview with Lidz verbatim, but I can restate its content.

When the interviewer asked if Lidz was surprised that books on schizophrenia, like those by Ronald Laing, had become popular among young people (this is a 1971 book and reflected the mood of the 1960s), Lidz replied that he was surprised that Laing wrote for the general public and not for a professional audience. What struck me as I reread that interview yesterday was that Lidz added that it wasn’t the public’s business to know what happens in these families, even though Laing might have altered the details to make his cases anonymous. Lidz added that, in his work on cases of schizogenic parents—that is, those who drive their children mad—he wasn’t able to publish the reports of most of the families because some of the parents were quite well-known, and even with pseudonyms, they could have been recognised. He added that some of the cases ran to 50 to 80 typewritten pages, ‘truly precious documents’, but that they couldn’t be published.

This struck me greatly because in my Letter to Mom Medusa, I cite a case in which Lidz violated what he said above: the case of Mrs Newcomb (a pseudonym) and her extremely passive husband, who helped me so much in understanding my parents.

On the next page I reread yesterday, Lidz, with whom I spoke on the phone in the 1990s when he was already quite old, surprised me again because he wrote that he didn’t believe the schizogenic parents had done anything wrong; that they hadn’t meant to harm the child, and that this contrasted with what Laing wrote, for whom the parents’ intentions were often malicious. Lidz added, and here I retranslate it again from my Spanish copy into English, that ‘parents do the best they can—they can’t be different from what they are’.

This goes against the thesis of my autobiographical books, where I say that my father could have chosen the good: not to be influenced by the lies his wife told about me, but rather should have communicated with me in my adolescence (cf. both the final pages of Hojas Susurrantes and the first chapter of ¿Me Ayudarás?).

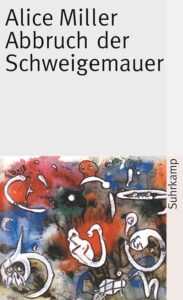

It’s been forty-two years since I first read the very lucid interview with Lidz standing in the Gandhi Bookstore, an interview that was a turning point in the research I did on my parents. It’s only natural that after so many years, my thinking has matured, largely due to the work of Alice Miller: the first psychologist in history who, unlike her predecessors (like Lidz), unequivocally took the side of the victimized child. (Despite what Lidz said, Laing didn’t completely side with the victim either, as we see in the middle chapter of my Hojas Susurrantes.)

In the previous thread, Benjamin complained that the racial right couldn’t care less about the issue, to which I responded that the German woman who received the mantle after Alice Miller died said that blaming parents is the most potent taboo in the human psyche. I’m posting this entry because, I see now, the taboo was present even in the works of my admired mentors, whom I read decades ago. The abysmal difference between them and us is that, in siding with the victim, we don’t care about what Lidz and company feared: that the public would realise which families the clinical material refers to, those ‘truly precious documents’ he didn’t dare publish (and which would have done enormous good for our cause had they been published!).

Do you now understand the new literary genre that people like John Modrow, Benjamin and I want to inaugurate? By siding a hundred per cent with the victim, not only do we not care about people recognising the abusive families, but we write using their real names!

Only revenge heals the wounded soul, even though we’re talking about literary revenge.