‘But if’, I am told, ‘in the view of the man above Time, the future is ‘given’ in the same way as the past, what becomes of the notions of freedom and responsibility? If a wise man can see, centuries in advance, how long a civilising doctrine is destined to retain its credit with one or more peoples, what is the use of militating ‘for’ or ‘against’ anything?

I believe that there are, in response to this, a few remarks to be made. Firstly, it should be pointed out that all action—in the sense that we understand it when we speak of ‘struggle’ and ‘activists’, or when we have in mind the gestures of everyday life—is intimately linked to the notion of time (of time at the very least, if not moreover of space). We should then note that the philosophical concepts of freedom and responsibility only make sense in connection with an action, direct or indirect—actual or possible, or even materially impossible to direct or modify on behalf of whoever conceives it, as is for example the case of any action thought of in retrospect—but always with an action, which could or should have been thought of. Finally, it must be understood that, as a consequence of this, these notions no longer have any meaning when, from the temporal state, one rises to that of consciousness outside time.

For those who are placed in the ‘eternal present’, i.e. outside of time, there is no question of freedom or responsibility, but only of being and non-being; of possibility and absurdity. The world that we see and feel, that others have seen and felt or will see and feel—a set of indefinite possibilities that have taken or will take shape—is simply what it is and, given that the intimate nature of each limited (individual) existence cannot be anything else. The consciousness above Time ‘sees’ it, but does not take part of it, even though it sometimes descends into it as a clairvoyant instrument of necessary action.

The beings that cannot think, because they are deprived of the word, thus of the general idea, nevertheless act and are not responsible. They behave according to their nature, and could not behave differently. And ‘to be free’, for them, consists simply in not being thwarted in the manifestation of their spontaneity in the exercise of their functions by some external force: not to be locked up between four walls or the bars of a cage; not to wear a harness or muzzle; not to be tied up, or deprived of water or food, or access to individuals of the same species and the opposite sex, and in the case of plants not to be deprived of water, soil and light, and not to be diverted in their growth by any obstacle.

It may be added that most humans are, although they can speak, neither freer nor more responsible than the humblest of beasts, or even of plants. Exactly like the rest of living, they do what their instincts, their appetites, and the demands of the moment urge them to do, and this, insofar as external obstacles and constraints allow. At most, many of them believe themselves to be responsible, having heard it repeated that this is ‘the nature of man’, and they feel, among the fridge, the washing machine and the television set—well as in the factories and offices where they spend eight hours a day under the blinding neon light—that they are less captive than the unfortunate tigers in the Zoological Garden. This only tends to show that the tigers are healthier in body and mind than they are, since they are aware of their captivity, and suffer from it.

Freedom[1] and responsibility are to be sought in different degrees between these extreme planes which are either active in time without thought, or consciousness outside of time without action, or accompanied by a completely detached, impersonal action, accomplished per an objective need. In other words, in an absolute sense, no one is ‘free’, if ‘freedom’ means the power to direct the future as one pleases.

The future is all oriented, since few wise men know it in advance, or rather who apprehend it as a ‘present’. But it is undeniable that the man of goodwill who lives and thinks in time has the impression of choosing between two or more possibilities; that he has the impression that the future, at least in its immediate course (and also in its distant course if it is a question of a decision of obvious historical significance) depends partly and sometimes entirely on him. This is, no doubt, only an impression. But it is an impression of such tenacity that it is impossible to ignore it, psychologically speaking. It forms so much a part of the experience of every man who must act in time, that it persists, even if that man is informed in advance (either by an invincible intuition, or by the evidence of one fact after another, or by some prophecy to which he gives credence) of what the future will be despite his action.

______ 卐 ______

Editor’s Note:

When Savitri wrote her book the criticisms of purported precognitions had not been popularised.

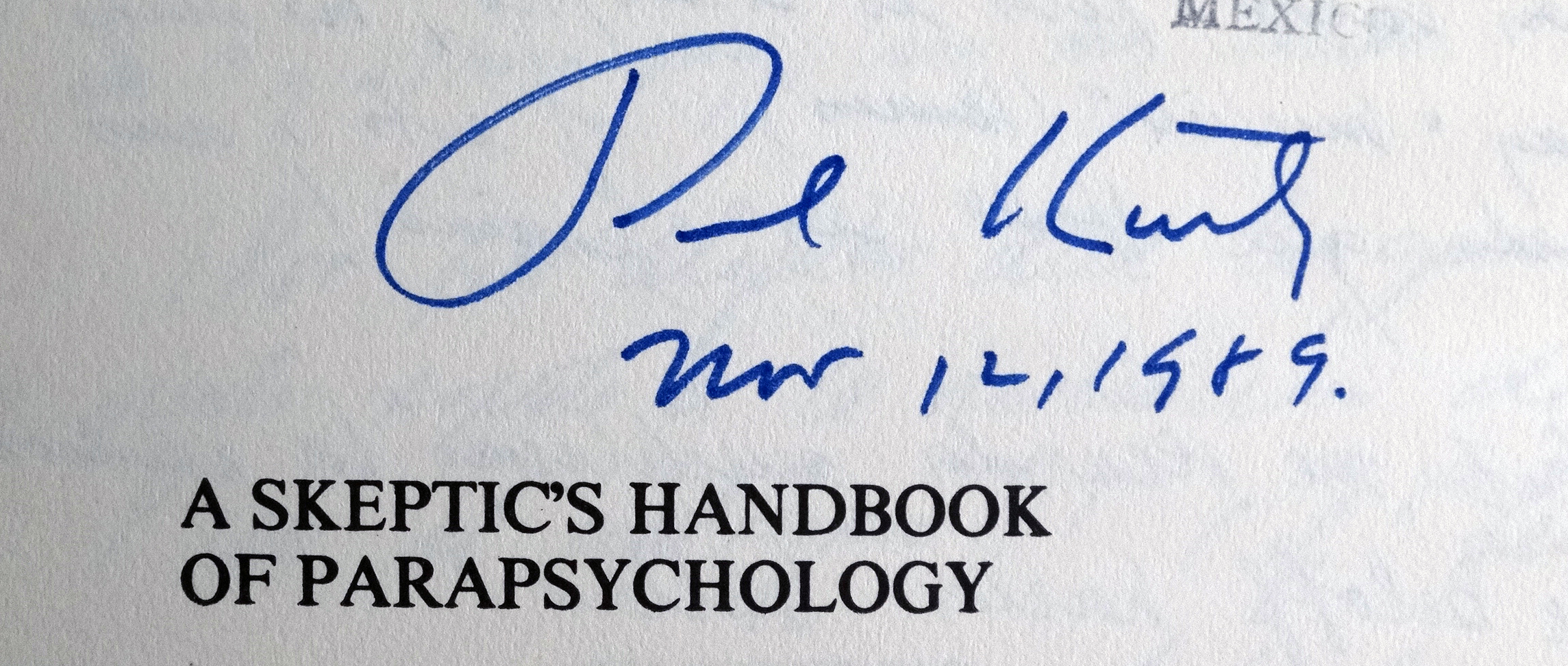

As I already said a couple of years ago, when I lived in Marin County, in 1985 I had the opportunity to realise that the foundations of the ‘science’ I was studying were shaky. In a bookstore I saw that they sold the recently published A Skeptic’s Handbook of Parapsychology. Decades have passed since that night and I still remember the image of James Randi on the dustcover.

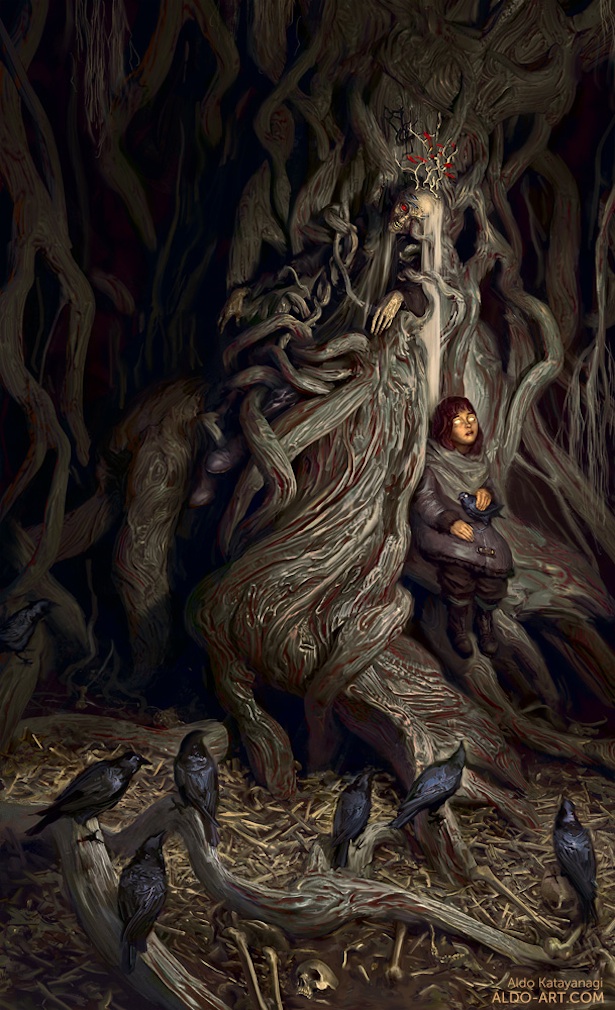

But as an immigrant who still had to get a job in the US for elemental survival, I thought I couldn’t afford it. If I had obtained a copy, years of my life would have been spared from my quixotic project of trying to develop psi and become a Bran before Martin wrote his novel!

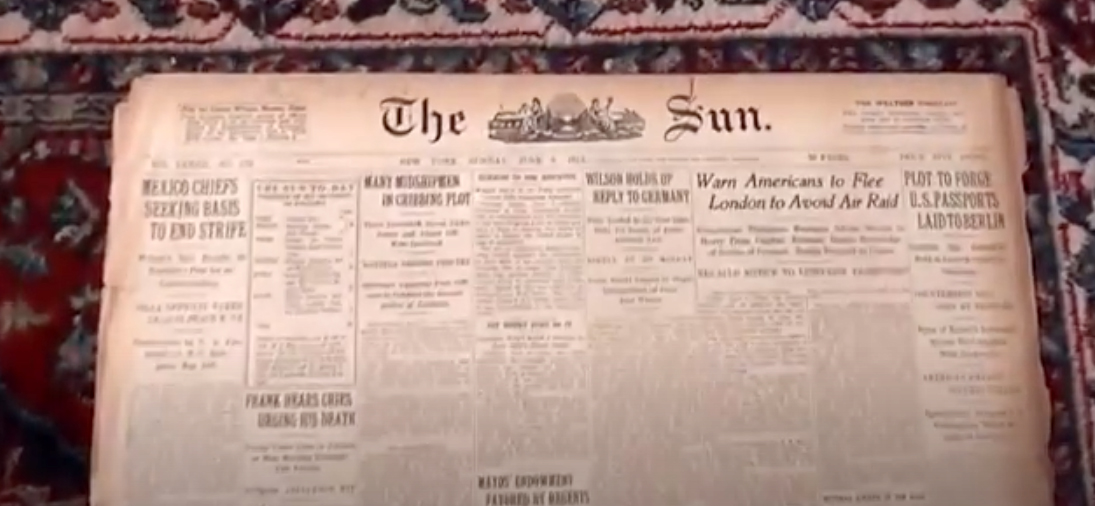

(Left, the signature of the book’s editor on the first page when he visited Mexico City and I was, finally, able to purchase it at a reasonable price for my modest income.) The difference between the priest and the priestess, is that the priest already had the opportunity to read books like this one because he was born half a century after the priestess…

(Left, the signature of the book’s editor on the first page when he visited Mexico City and I was, finally, able to purchase it at a reasonable price for my modest income.) The difference between the priest and the priestess, is that the priest already had the opportunity to read books like this one because he was born half a century after the priestess…

______ 卐 ______

[1] We are talking here, of course, about freedom in the sense that this word is generally understood, not about ‘freedom’ in the metaphysical sense in which René Guénon understands it, for example.