Or:

On putting the chariot before the horse

There is something important I would like to add to my Thursday post, in which I used a 1993 interview between Tom Metzger and James Mason to say something about Richard Spencer.

On this site I have been very critical of James Mason and his epigones for admiring Charles Manson: the mastermind behind the stabbing to death of the beautiful English rose Sharon Tate (and other Hollywood showbiz personalities).

In Siege Mason compiles his articles from the journal he wrote in the early 1980s. In vain, when I was reading Siege, did I find the reasons why Mason admired Manson, insofar as the latter’s intentions in devising his crimes weren’t racial. But now that I re-watched his interview with Metzger I detected something I had missed the first time I saw it. But before this revelation about the mind of James Mason I would like to digress a little.

Unlike Metzger’s audio-visual interviews, the podcasts of Greg Johnson, one of the leading promoters of American white nationalism, are audio-only. Metzger, let alone Mason, not properly ‘white nationalists’, were infinitely closer in character to the Germans of the Third Reich than Johnson and Spencer. But in one of his podcasts Johnson said something that piqued my interest. He mentioned the decades immediately before the internet as the darkest era, in that the Establishment had virtually absolute control over the narrative. This is very true: and the new generations have no idea how impossible it was for us to find even dissident authors, to the extent that in the past we could never rebel. (Since I grew up in the 1960s and 70s I couldn’t rebel intellectually because of this absolute control of information, as I recount in the third volume of my autobiography.)

Now let’s get back to Mason’s infatuation with Manson. What I detected in the interview with Metzger, which I had missed the first time I saw it, was that the desperation of national socialists like Mason in the face of the System’s absolute control of the media meant that he began to fix his attention on the news of those who broke the law with crimes to shock public morals. It was, it seemed, the only escape valve from an Establishment that was entirely successful in suppressing dissenting opinion.

This revelation came to me in understanding Mason when Metzger asked him why he admired Charles Manson. From Mason’s response, Metzger commented that, given the impasse on all sides due to the absolute grip of the System, the whole thing had to be blown up. (Recall that Charles Manson is not the only criminal to whom James Mason devotes articles in Siege: he also discusses other criminals who, at the time, shocked public morals even though, like Manson, weren’t acting out of racial ideals either.)

That doesn’t mean that, having understood the point James Mason wanted to get across, I now approve of the behaviour of Charles Manson and company. But it does mean that what I didn’t understand years ago when I read Siege directly, I understand now having watched the splendid interview with Metzger again. As I said, for new generations it is almost impossible to imagine the prolonged despair, a suffocation of ideas I dare say, that it meant for noble-minded boomers that there was no relevant information anywhere!

But back to James Mason. While I don’t join his enthusiasm for criminals who acted without racial ideology, what about those who break the law with racial ideology: say, someone like Breivik or Tarrant? In the 2020 discussion thread on the Metzger/Mason interview, one of the commenters chided me because I said that any revolutionary action is premature:

You sound like an old and grumbling geezer.

It’s futile and unfair to accuse the youth of ardour and impatience and narrow tunnel vision. Many of them are sincerely actuated by a heroic impulse to over with this shameful state of things, this disgraceful status quo. Their hearts volcanically explodes with lava of despair and hatred for the world of their worthless parents and cowardly ancestors. Yes, the lives of foolhardy men usually end not well. And tragic triumph is a fate of exceptional ones.

But the young soul has no time to wait, be it in love or war. So, be lenient towards suicidal behaviour of the youth and do not impute to passionate youngsters the carelessness concerning those fucking Austrian economists! All this cultural and historic noise–million words in billion posts–is not a groundwork or an earnest or a linchpin or a promise of coming transvaluation of values.

They dread reaching your age, Caesar, and face their death, especially after a very long life, and realize that all their efforts failed to produce results, moreover the situation has got worse. They know some examples of lustrous persons, whose deeds were vain in spite of their “strategic thinking”. By the way, traitors often justify their betrayal with strategical manoeuvring for the sake of a lofty goal in long-term planning.

The destiny occurs HERE AND NOW, and if this “here and now” is stolen, I will not judge the glowing souls with the destructive power of dynamite inside their cores.

I confess that, now that I re-read my comment years later, I see that I responded to this commenter in a very, very poor way! I would like to reply to him now, even though so much time has passed.

It is not for the youth to make the most important decisions of a state. In a healthy world for the Aryans, as was Sparta, and Republican Rome, it was up to very mature adults. Recall that, for Plato, the philosopher-king had to be a man in his sixties.

To be impetuous, fiery, determined or bold against the System is precisely what President Joe Biden wants to tighten the screws even further (remember his inaugural speech in which he declared war on us). We shouldn’t indulge him because his administration is doing everything it can to commit suicide. The situation in 2023 has changed a lot from the days when, in 2020, the commenter mocked what I said about Austrian economists. Now, after Biden’s blunder with the confiscation of Russian funds abroad due to Putin’s military action in Ukraine, several nations have realised that their funds aren’t safe in dollars and many, even in the MSM, are already openly talking about the last days of the dollar. In other words, my restraint not to rush into revolutionary actions as impetuous youths love, but to wait for the System to collapse on its own, is being vindicated by recent historical events.

But there are even more profound reasons why I think James Mason’s ideology—something like having the System in siege with a multiplication of actions à la Charles Manson—is flawed. And here we come back to what Spencer said in his recent interview: that we need a new story or, as I would say using Jungian language, a story that manages to activate the collective Self that will produce, in the white man, the new galvanising myth. Ironically, in this respect James Mason did hit the nail on the head: ‘Someone did say that prior to 1945 we were a party, since 1945 we have been a religion.’

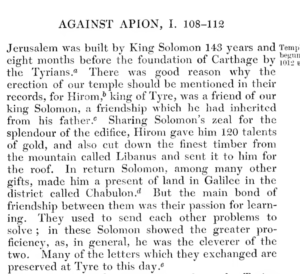

Indeed. The Jews have their religion, their story: what Christians call the Old Testament: ‘Ethnocentrism for me’ as Kevin MacDonald reads it in the first book of his trilogy on Jewry. That’s why they always win. It doesn’t matter that their story, what we read in the OT, is literary fiction. It is a myth they believe in and that’s why they will continue to win.

Conversely, whites didn’t write their story, the New Testament. The Jews wrote it for them: ‘Universalism for thee.’ And liberalism, which has mutated into Wokism, the secular neo-Christianity of our day, is an epiphenomenon of that NT story.

The moral is simple: it’s whites themselves who must rewrite their own history. They mustn’t allow another race to write it for them. If one reads the first anthology published by us, The Fair Race’s Darkest Hour, one will discover seminal texts by William Pierce, and Eduardo Velasco in his now-defunct webzine Evropa Soberana, which depict this story written by whites for whites.

And now I can answer properly to the commenter who criticised me. ‘All this cultural and historic noise–million words in billion posts–is not a groundwork or an earnest or a linchpin or a promise of coming transvaluation of values’ he said.

Actually, it is. Any revolutionary action that is not backed by a new story, a new way of understanding the Self, is doomed to failure. James Mason’s own life demonstrates this. After the Metzger interview, Mason went astray with so-called Christian Identity. A dozen years after the interview Metzger himself commented, on 17 May 2005: ‘Unfortunately he turned away from his best thoughts back toward some Christian thing. I don’t know where he is now, but I promote and sell his great book.’

The eclipse of James Mason is symptomatic not only of would-be revolutionaries, but of non-revolutionaries who subscribe to white nationalism. They lack a story to serve as cement and a platform for further action. The fact that very few have read the history of the white race from Pierce’s pen, and that even that book isn’t published (even privately) so that you can read it comfortably in your living room, speaks for itself.

This is the response of a sixty-four-year-old man to the young commenter:

You are putting the chariot before the horse. First goes the horse—the new story that will galvanise the white man’s collective unconscious—and then goes the chariot (the holy racial wars). Reversing the sequence yields results such as what happened to James Mason and his unfortunate epigones, inasmuch as Mason was completely ignorant of the real history of Christianity (which we are telling on this site thanks to the work of Karlheinz Deschner).

The central mission of The West’s Darkest Hour is that, when the System panics and cancels the internet, there remain on my visitors’ hard drives the PDF books from my humble Daybreak Press, which provide the new story the white man must tell himself.

Anyone who hasn’t read The Fair Race should read it now. The rest follows from it.