‘Paul hardly ever allows the real

Jesus of Nazareth to get a word in’.

—Carl Jung

‘Paul hardly ever allows the real

Jesus of Nazareth to get a word in’.

—Carl Jung

I have in my library Nikos Kazantzakis’ The Last Temptation of Christ. Although it’s not a good novel, it contains a masterpiece: an imaginary dialogue between Paul and Jesus: also, the only redeemable scene in Scorsese’s adaptation of Kazantzakis’s novel.

‘If, in his time, a being there was, in whom, with the exception of two or three attendants of his own, every person, that bore the name of Christian, beheld and felt an opponent, and that opponent an indefatigable adversary, it was this same Paul: Yes, such he was, if, in this particular, one may venture to give credence, to what has been seen so continually testified—testified, not by any enemy of his, but by his own dependent, his own historiographer, his own panegyrist, his own steady friend (Luke, in Acts). Here then, for any body that wants an Antichrist, here is an Antichrist, and he an undeniable one’ (Not Paul, but Jesus, London, 1823, page 372).

—Jeremy Bentham

‘The new testament was less a Christiad than a Pauliad’.

‘Paul created a theology of which none but the vaguest warrants can be found in the words of Christ… Fundamentalism is the triumph of Paul over Christ’.

—Will Durant

‘Where possible Paul avoids quoting the teachings of Jesus, in fact even mentioning it. If we had to rely on Paul, we should not know that Jesus taught in parables, had delivered the sermon on the mount, and had taught his disciples the “Our Father”.’

—Albert Schweitzer

‘Paul was the first corrupter of the doctrines of Jesus’.

—Thomas Jefferson

Editor’s Note: The book of Porphyry, of which the Christians destroyed all the copies and only fragments remain, is worth more than the opus of all Christian theologians together.

Yesterday I sent a message to Joseph Hoffmann, author of Porphyry’s ‘Against the Christians’: The Literary Remains. I asked him if he is willing to republish it in Lulu, as it is out-of-print (I own the copy I purchased in 1994).

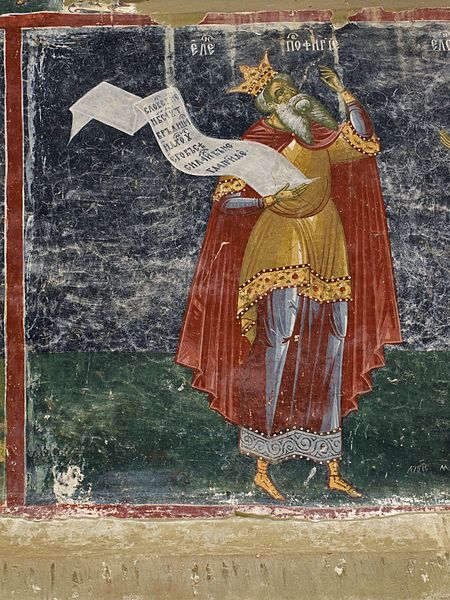

Porphyry, a detail of the Tree of

Jesse, 1535, Sucevița Monastery.

______ 卐 ______

Below, abridged translation from the first volume of Karlheinz

Deschner’s Kriminalgeschichte des Christentums

(Criminal History of Christianity)

Celsus and Porphyry: the first adversaries of Christianity

Before looking more closely at these new Christian majesties, let us look briefly at two of the first great adversaries of Christianity in antiquity.

Soon the pagans knew how to spot the weak points in the argument of the holy fathers and refute them, when not leading them ad absurdum.

While it is true that the first Christian emperors ordered the destruction of the anti-Christian works of these philosophers, it is possible to reconstruct them in part by cutting off the treatises of their own adversaries. Celsus’ work in particular is derived from a response of eight books written by Origen about 248. The most influential theologian of the early days of Christendom evidently took a lot of work in refuting Celsus, which is all the more difficult because in many passages he was forced to confess the rationale of his adversary.

In spite of being one of the most honest Christians that can be mentioned, and in spite of his own protests of integrity, in many cases Origen had to resort to subterfuges, to the omission of important points, and accuses Celsus of the same practices. Celsus was an author certainly not free of bias but more faithful to the reality of the facts. Origen reiterates his qualification of him as a first-class fool, although having bothered to write an extended replica ‘would rather prove the opposite’ as Geffcken says.

The True Word (Alethés Logos) of Celsus, originating from the end of the 2nd century, is the first diatribe against Christianity that we know. As a work of someone who was a Platonic philosopher, the style is elegant for the most part, nuanced and skilful, sometimes ironic, and not completely devoid of a will to conciliation. The author is well versed in the Old Testament, the Gospels, and also in the internal history of the Christian communities. Little we know of his figure, but as can be deduced from his work he was certainly not a vulgar character.

Celsus clearly distinguished the most precarious points of Christian doctrine, for example the mixing of Jewish elements with Stoicism, Platonism, and even Egyptian and Persian mystical beliefs and cults. He says that ‘all this was best expressed among the Greeks… and without so much haughtiness or pretension to have been announced by God or the Son of God in person’.

Celsus mocks the vanity of the Jews and the Christians, their pretensions of being the chosen people: ‘God is above all, and after God we are created by him and like him in everything; the rest, the earth, the water, the air and the stars is all ours, since it was created for us and therefore must be put to our service’. To counter this, Celsus compares ‘the thinness of Jews and Christians’ with ‘a flock of bats, or an anthill, or a pond full of croaking frogs or earthworms’, stating that man does not carry as much advantage to the animal and that he is only a fragment of the cosmos.

From there, Celsus is forced to ask why the Lord descended among us. ‘Did he need to know about the state of affairs among men? If God knows everything, he should already have been aware, and yet he did nothing to remedy such situations before’. Why precisely then, and why should only a tiny part of humanity be saved, condemning others ‘to the fire of extermination’?

With all reason from the point of view of the history of religions, Celsus argues that the figure of Christ is not so exceptional compared to Hercules, Asclepius, Dionysus and many others who performed wonders and helped others.

Or do you think that what is said of these others are fables and must pass as such, whereas you have given a better version of the same comedy, or more plausible, as he exclaimed before he died on the cross, and the earthquake and the sudden darkness?

Before Jesus there were divinities that died and resurrected, legendary or historical, just as there are testimonies of the miracles that worked, along with many other ‘prodigies’ and ‘games of skill that conjurers achieve’. ‘And they are able to do such things, shall we take them for the Sons of God?’ Although, of course, ‘those who wish to be deceived are always ready to believe in apparitions such as the ones of Jesus’.

Celsus repeatedly emphasises that Christians are among the most uncultured and most likely to believe in prodigies, that their doctrine only convinces ‘the most simple people’ since it is ‘simple and lacks scientific character’. In contrast to educated people, says Celsus, Christians avoid them, knowing that they are not fooled. They prefer to address the ignorant to tell them ‘great wonders’ and make them believe that

parents and teachers should not be heeded, but listened only to them. That the former only say nonsense and foolishness and that only Christians have the key of the things and that they know how to make happy the creatures that follow them… And they insinuate that, if they want, they can abandon their parents and teachers.

A century after Celsus, Porphyry took over the literary struggle against the new religion. Born about 233 and probably in Tyre (Phoenicia), from 263 Porphyry settled in Rome, where he lived for decades and became known as one of the main followers of Plotinus.

Of the fifteen books of Porphyry’s Adversus Christianos (Against the Christians), fruit of a convalescence in Sicily, today only some quotations and extracts are preserved. The work itself was a victim of the decrees of Christian princes, Constantine I and then, by 448, the emperors Theodosius II and Valentinian III who ordered the first purge of books in the interest of the Church.

Unfortunately, the conserved references of the work do not give as complete an idea as in the case of Celsus. We may suppose that Porphyry knew The True Word; some arguments are repeated almost verbatim, which is quite logical. As to the coming of Christ Porphyry asks, for example, ‘Why was it necessary to wait for a recent time, allowing so many people to be damned?’

Porphyry seems more systematic than Celsus, more erudite; he excels as a historian and philologist, as well as in the knowledge of the Christian Scriptures. He masters the details more thoroughly and criticises the Old Testament and the Gospels severely; discovers contradictions, which makes him a forerunner of the rationalistic criticism of the Bible. He also denies the divinity of Jesus: ‘Even if there were some among the Greeks so obtuse as to believe that the gods actually reside in the images they have of them, none would be so great as to admit that the divinity could enter the womb of virgin Mary, to become a foetus and be wrapped in diapers after childbirth’.

Porphyry also criticises Peter, and above all Paul: a character who seems to him (as to many others to date) remarkably disagreeable. He judges him ordinary, obscurantist and demagogue. He even claims that Paul, being poor, preached to get money from wealthy ladies, and that this was the purpose of his many journeys. Even St Jerome noticed the accusation that the Christian communities were run by women and that the favour of the ladies decided who could access the dignity of the priesthood.

Porphyry also censures the doctrine of salvation, Christian eschatology, the sacraments, baptism and communion. The central theme of his criticism is, in fact, the irrationality of the beliefs and, although he does not spare expletives, Paulsen could write in 1949:

Porphyry’s work was such a boast of erudition, refined intellectualism, and a capacity for understanding the religious fact, that it has never been surpassed before or since by any other writer. It anticipates all the modern criticism of the Bible, to the point that many times the current researcher, while reading it, can only nod quietly to this or that passage.

The theologian Harnack writes that ‘Porphyry has not yet been refuted’, ‘almost all his arguments, in principle, are valid’.

Editor’s note: Modern scholarship differs from the traditional view that the Book of Revelation was penned by John the Apostle. Taking into account the author’s infinite hatred of the Romans precisely in the aftermath of the destruction of the Temple of Jerusalem (‘lake of fire’, etc.), my educated guess is that ‘John of Patmos’ probably had Jewish ancestry.

______ 卐 ______

Below, abridged translation from the first volume of Karlheinz

Deschner’s Kriminalgeschichte des Christentums

(Criminal History of Christianity)

Anti-pagan hate in the New Testament

Paul’s preaching against the pagans was far more moderate than against ‘heretics’ and Jews. Often, he tries to counter them, and manifestations of clear preference in favour of ‘idolaters’ are not uncommon. Just as he wanted to be an ‘apostle of the Gentiles’, and says that they will participate in the ‘inheritance’ and promise them ‘salvation’, he also adhered to pagan authority, which he says ‘comes from God’ and represents ‘the order of God’ and ‘not from one who girds the sword’. A sword that, incidentally, finally fell on him, and that counting that, in addition, he had been flogged in three occasions despite his citizenship, and imprisoned seven times.

Paul did not see anything good in the pagans, but he thinks that they ‘proceed in their conduct according to the vanity of their thoughts’, ‘their understanding is darkened and filled with shadows’, have ‘foolish’ heart, are ‘full of envy’ with ‘homicides, quarrelsome, fraudulent and evil men, gossipers’, and ‘they did not fail to see that those who do such things are worthy of death.’

All this, according to Paul (and in this he completely agreed with the Jewish tradition so hated by him), was a consequence of the worship of idols, which could only result in greed and immorality; to these ‘servants of the idols’ he often names them with the highwaymen. Moreover, he calls them infamous, enemies of God, arrogant, haughty, inventors of vices, and warns about their festivities; prohibits participation in their worship, their sacramental banquets, ‘diabolical communion’, ‘diabolical table’, ‘cup of the devil’. These are strong words. And their philosophers? ‘Those who thought themselves wiser have ended up as fools’.

We can go back even further, however, because the New Testament already burns in flames of hatred against the Gentiles. In his first letter, Peter does not hesitate to consider as the same the heathen lifestyle and ‘the lusts, greed, drunkenness and abominable idolatries’.

In the Book of Revelation of John, Babylon (symbolic name of Rome and the Roman Empire) is ‘dwelling with demons’, ‘the den of all unclean spirits’; the ‘servants of the idols’. It is placed next to the murderers, together with ‘the wicked and evildoers and assassins’, the ‘dishonest and sorcerers… and deceivers, their lot will be in the lake that burns with fire and brimstone’ because paganism, ‘the beast’, must be ‘Satan’s dwellings’, where ‘Satan has his seat’.

That is why the Christian must rule the pagans ‘with a rod of iron, and they will be shredded like vessels of potter’. All the authors of the first epoch, even the most liberal as emphasized by E.C. Dewik, assume ‘such enmity without palliatives’.

Below, abridged translation from the first

volume of Karlheinz Deschner’s Kriminalgeschichte

des Christentums (Criminal History of Christianity)

______ 卐 ______

Chapter 3:

First malicious acts of Christians against Christians

‘No heretic is a Christian. But if he is not a Christian, every heretic is a devil.’ ‘Cattle for the slaughter of hell.’

—St Jerome, Doctor of the Church

In the origins of Christianity there was no ‘true faith’

The Church teaches that the original situation of Christianity was of ‘orthodoxy’, that is, of ‘true faith’; later, the ‘heresy’ would appear (de aíresis = the chosen opinion)… In classical literature it was called ‘heresy’ any opinion, whether scientific, political or from a religious party. Little by little, however, the term took on the connotation of the sectarian and discredited.

Now, the scheme ‘original orthodoxy against overcoming heresy’, essential to maintain the ecclesiastical fiction of an allegedly uninterrupted and faithfully preserved apostolic tradition, is nothing more than an a posteriori invention and as false as that same doctrine of the apostolic tradition. The historical model according to which Christian doctrine, in its beginnings, was pure and true, then contaminated by heretics and schismatics of all epochs, ‘the theory of deviationism’, as the Catholic theologian Stockmeier has written, ‘does not conform to any historical reality’.

Such a model could not be true in any way, because Christianity in its beginnings was far from being homogeneous; there existed only a set of beliefs and principles not very well established. It still ‘had no definite symbol of faith (a recognised Christian belief) nor canonical Scriptures’ (E.R. Dodds). We cannot even refer to what Jesus himself said, because the oldest Christian texts are not the Gospels, but the Epistles of Paul, which certainly contradict the Gospels in many essential points, not to mention many other problems of quite transcendence that arise here.

The early Christians incorporated not one, but many and very different traditions and forms. In the primitive community there was at least one division, as far as we know, between the ‘Hellenizing’ and the ‘Hebrew’. There were also violent discussions between Paul and the first original apostles… Ever since, every tendency, church or sect, tends to be considered as the ‘true’, the ‘unique’, authentic Christianity. That is, in the origins of the new faith there was neither a ‘pure doctrine’ in the current Protestant sense, nor a Catholic Church. It was a Jewish sect separated from its mother religion…

At the end of the second century, when the Catholic Church was constituted, that is, when the Christians had become a multitude, as the pagan philosopher Celsus joked, divisions and parties began to emerge, each of which called for their own legitimacy, ‘which was what they intended from the outset.’

And as a result of having become a multitude, they are distant from each other and condemn each other, to the point that we do not see that they have anything in common except the name, since otherwise each party believes in its own and has nothing in the beliefs of others.

At the beginning of the third century, Bishop Hippolytus of Rome cites 32 competing Christian sects which, by the end of the fourth century, according to Bishop Philastrius of Brescia, numbered 128 (plus 28 ‘pre-Christian heresies’). Lacking political power, however, the pre-Constantinian Church could only verbally vent against the ‘heretics’, as well as against the Jews. To the ever-deeper enmity with the synagogue, were thus added the increasingly odious clashes between the Christians themselves, owing to their doctrinal differences.

Moreover, for the doctors of the Church, such deviations constituted the most serious sin, because divisions, after all, involved the loss of members, the loss of power. In these polemics the objective was not to understand the point of view of the opponent, nor to explain the own, which perhaps would have been inconvenient or dangerous. It would be more accurate to say that they obeyed the purpose ‘to crush the contrary by all means’ (Gigon). ‘Ancient society had never known this kind of quarrel, because it had a different and non-dogmatic concept of religious questions’ (Brox).

First ‘heretics’ in the New Testament

Paul the fanatic, the classic of intolerance, provided the example of the treatment that would be given by Rome to those who did not think like her, or rather, ‘his figure is fundamental to understand the origin of this kind of controversy’ (Paulsen).

This was demonstrated in his relations with the first apostles, without excepting Peter. Before the godly legend made the ideal pair of the apostles Peter and Paul (still in 1647, Pope Innocent X condemned the equation of both as heretical, while today Rome celebrates its festivities the same day, June 29), the followers of the one and the other, and themselves, were angry with fury; even the book of the Acts of the Apostles admits that there was ‘great commotion.’

This was demonstrated in his relations with the first apostles, without excepting Peter. Before the godly legend made the ideal pair of the apostles Peter and Paul (still in 1647, Pope Innocent X condemned the equation of both as heretical, while today Rome celebrates its festivities the same day, June 29), the followers of the one and the other, and themselves, were angry with fury; even the book of the Acts of the Apostles admits that there was ‘great commotion.’

Paul, despite having received from Christ ‘the ministry of preaching forgiveness’, contradicts Peter ‘face to face’, accuses him of ‘hypocrisy’ and asserts that with him, ‘the circumcised’ were equally hypocrites. He makes a mockery of the leaders of the Jerusalem community, calling them ‘proto-apostles’, whose prestige he says nothing matters to them, since they are only ‘mutilated’, ‘dogs’, ‘apostles of deceit.’ He regrets the penetration of ‘false brethren’, the divisions, the parties, even if they were declared in his favour, to Peter or to others.

Conversely, the primitive community reproached him those same defects, and even more, including greed, accusing him of fraud and calling him a coward, an abnormal and crazy, while at the same time seeking the defection of the followers. Agitators sent by Jerusalem break into his dominions, even Peter, called ‘hypocrite’, faces in Corinth the ‘erroneous doctrines of Paul’. The dispute did not stop to fester until the death of both and continued with the followers.

Paul, very different to the Jesus of the Synoptics, only loves his own. Overbeck, the theologian friend of Nietzsche who came to confess that ‘Christianity cost my life… because I have needed my whole life to get rid of it’, knew very well what was said when he wrote: ‘All beautiful things of Christianity are linked to Jesus, and the most unpleasant to Paul. He was the least likely person to understand Jesus’.

To the condemned, this fanatic wants to see them surrendered ‘to the power of Satan’, that is to say, prisoners of death. And the penalty imposed on the incestuous Corinth, which was pronounced, by the way, according to a typically pagan formula, was to bring about its physical annihilation, similar to the lethal effects of the curse of Peter against Ananias and Sapphira.

Peter and Paul and Christian love! Whoever preaches another doctrine, even if he were ‘an angel from heaven’, is forever cursed. And he repeats, tirelessly, ‘Cursed be…!’, ‘God would want to annihilate those who scandalize you!’, ‘Cursed be everyone who does not love the Lord’, anatema sit that became a model of future Catholic bulls of excommunication. But the apostle was to give another example of his ardour, to which the Church would also set an example.

In Ephesus, where ‘tongues’ were spoken, and where even the garments used by the apostles heal diseases and cast out devils, many Christians, perhaps disillusioned with the old magic in view of the new wonders, ‘collected their books and burned them up in the presence of everyone. When the value of the books was added up, it was found to total fifty thousand silver coins. In this way the word of the Lord spread widely and grew in power.’

The New Testament already identifies heresy with ‘blasphemy against God’, the Christian of another hue with the ‘enemy of God’; and Christians begin to call other Christians ‘slaves of perdition’, ‘adulterous and corrupted souls’, ‘children of the curse’, ‘children of the devil’, ‘animals without reason and by nature created only to be hunted and exterminated’, in which the saying that ‘the dog always returns to his own vomit’ and ‘the pig wallows in his own filth’ is confirmed.