It is true that this site focuses on the Christian problem. But that does not mean that I believe that Christian ethics is the sole sin in white decline. Our focus is due to the fact that no Alt-Right site is exposing such sin as a factor to be studied.

There are other cardinal sins. Recently for example Tom Sunic said: ‘Both the early liberals C. Montesquieu and later A. Smith wrote that “merchant ignores all borders.” This is how the West was designed by the world improvers in the wake of WWII’.

In other words, in addition to Christian ethics being a pig is a major factor in the downfall of whites!

Category: Montesquieu

Below, abridged translation from the first

volume of Karlheinz Deschner’s Kriminalgeschichte

des Christentums (Criminal History of Christianity)

Christian tall stories

Christians, preachers of love of the enemy and of the doctrine that all authority emanates from God, celebrated the death of the emperor with great public banquets, with festivals in churches and chapels and dances in the theatres of Antioch: the city that, as Ernest Renan says, ‘was full of puppeteers, charlatans, actors, magicians, thaumaturges, witches and religious swindlers’.

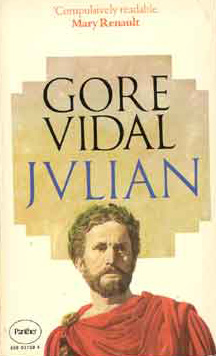

The diatribe in three volumes that Julian had written shortly before his death, Against the Galileans, was promptly destroyed, but fifty years later, Cyril, the doctor of the Church still bothered to argue against it: Pro sanela Christianorum religione adversas libros athei Julian in thirty volumes, of which ten have reached us in their Greek text and ten others in Greek and Syriac fragments. Naturally, a bishop like Cyril, an avowed enemy of philosophy who even tried to prohibit its teaching in Alexandria, did not intend to grasp the thought of Julian, but only ‘crush it with maximum energy’ (Jouassard).

The Christians also destroyed all the portraits of Julian and the epigraphs that commemorated his victories, without sparing means to erase from the memory of men the remembrances of him.

During Julian’s life, the most famous doctors of the Church had kept a prudent silence, but shortly after his death, and for a long time more, they dedicated themselves to attacking him.

Ephrem, another saint whose odious songs were repeated by the parishioners of Edessa, dedicated a whole treatise to ‘Julian the Apostate’, the ‘pagan emperor’ and, according to him, ‘frantic’, ‘tyrant’, ‘trickster’, ‘damned’ ‘and’ idolatrous priest’. ‘His ambition caught the deadly release’ that ‘tore his body pregnant with oracles from his magicians’ to send him definitively ‘to hell’. The clerical historians of the 5th century, who sometimes were also jurists, such as Rufinus, Socrates, Philostorgius, Sozomen and Theodoret, speak of Julian in a still worse tone.

While the Christian world defamed the ‘apostate’, as he usually does with its enemies, the Enlightenment corrected that image in the diametrically opposite sense.

In 1699, the Protestant theologian Gottfried Arnold, in his Impartial History of the Church and of Heresy, rehabilitated the figure of Julian.

A few decades later, Montesquieu praised him as a statesman and legislator. Voltaire wrote: ‘Thus, that man who has been described to us horribly was perhaps the most noble of all, or at least the second’. Montaigne and Chateaubriand count him among the greatest historical figures.

Goethe praised himself for understanding and sharing Julian’s animosity against Christianity. Schiller wanted to make him protagonist of one of his dramas.

Shaftesbury and Fielding praised him, and Gibbon believes that he deserved to have owned the world. Ibsen wrote Caesar and Galilee and Nikos Kazantzakis his tragedy Julian the Apostate, premiered in Paris in 1948.

More recently, between 1962 and 1964, the North American Gore Vidal dedicated a novel to him. On the other hand, the Benedictine Baur (representative, in this, of many current Catholics) continues to defame Julian in the 20th century.

After the death of Julian, and having renounced the designated successor, Salutius, a moderate pagan philosopher and prefect of the praetorians of the East who had been a personal friend of Julian, the Illyrian Jovian acceded to the throne.

Classical and modern

Enlightenment philosophers are given credit for shaping liberal ideas. Thomas Hobbes attempted to determine the purpose and the justification of governing authority in a post-civil war England. Employing the idea of a state of nature—a hypothetical war-like scenario prior to the State—he constructed the idea of a social contract which individuals enter into to guarantee their security and in so doing form the State, concluding that only an absolute sovereign would be fully able to sustain such a peace.

John Locke, while adopting Hobbes’s idea of a state of nature and social contract, nevertheless argued that when the monarch becomes a tyrant, that constituted a violation of the social contract, which bestows life, liberty, and property as a natural right. He concluded that the people have a right to overthrow a tyrant. By placing life, liberty and property as the supreme value of law and authority, Locke formulated the basis of liberalism based on social contract theory.

To these early enlightenment thinkers securing the most essential amenities of life—liberty and private property among them—required the formation of a “sovereign” authority with universal jurisdiction. In a natural state of affairs, liberals argued, humans were driven by the instincts of survival and self-preservation, and the only way to escape from such a dangerous existence was to form a common and supreme power capable of arbitrating between competing human desires. This power could be formed in the framework of a civil society that allows individuals to make a voluntary social contract with the sovereign authority, transferring their natural rights to that authority in return for the protection of life, liberty, and property.

These early liberals often disagreed about the most appropriate form of government, but they all shared the belief that liberty was natural and that its restriction needed strong justification. Liberals generally believed in limited government, although several liberal philosophers decried government outright, with Thomas Paine writing that “government even in its best state is a necessary evil”.

As part of the project to limit the powers of government, various liberal theorists such as James Madison and the Baron de Montesquieu conceived the notion of separation of powers, a system designed to equally distribute governmental authority among the executive, legislative, and judicial branches. Governments had to realize, liberals maintained, that poor and improper governance gave the people authority to overthrow the ruling order through any and all possible means, even through outright violence and revolution, if needed.

Contemporary liberals, heavily influenced by social liberalism, have continued to support limited constitutional government while also advocating for state services and provisions to ensure equal rights. Modern liberals claim that formal or official guarantees of individual rights are irrelevant when individuals lack the material means to benefit from those rights and call for a greater role for government in the administration of economic affairs.

Early liberals also laid the groundwork for the separation of church and state. As heirs of the Enlightenment, liberals believed that any given social and political order emanated from human interactions, not from divine will. Many liberals were openly hostile to religious belief itself, but most concentrated their opposition to the union of religious and political authority, arguing that faith could prosper on its own, without official sponsorship or administration by the state.

Beyond identifying a clear role for government in modern society, liberals also have obsessed over the meaning and nature of the most important principle in liberal philosophy: liberty. From the 17th century until the 19th century, liberals—from Adam Smith to John Stuart Mill—conceptualized liberty as the absence of interference from government and from other individuals, claiming that all people should have the freedom to develop their own unique abilities and capacities without being sabotaged by others. Mill’s On Liberty (1859), one of the classic texts in liberal philosophy, proclaimed that “the only freedom which deserves the name, is that of pursuing our own good in our own way”. Support for laissez-faire capitalism is often associated with this principle, with Friedrich Hayek arguing in The Road to Serfdom (1944) that reliance on free markets would preclude totalitarian control by the state.

Beginning in the late 19th century, however, a new conception of liberty entered the liberal intellectual arena. This new kind of liberty became known as positive liberty to distinguish it from the prior negative version, and it was first developed by British philosopher Thomas Hill Green. Green rejected the idea that humans were driven solely by self-interest, emphasizing instead the complex circumstances that are involved in the evolution of our moral character. In a very profound step for the future of modern liberalism, he also tasked society and political institutions with the enhancement of individual freedom and identity and the development of moral character, will and reason and the state to create the conditions that allow for the above, giving the opportunity for genuine choice. Foreshadowing the new liberty as the freedom to act rather than to avoid suffering from the acts of others, Green wrote the following:

If it were ever reasonable to wish that the usage of words had been other than it has been… one might be inclined to wish that the term “freedom” had been confined to the… power to do what one wills.

Rather than previous liberal conceptions viewing society as populated by selfish individuals, Green viewed society as an organic whole in which all individuals have a duty to promote the common good. His ideas spread rapidly and were developed by other thinkers such as L.T. Hobhouse and John Hobson.

In a few years, this New Liberalism had become the essential social and political program of the Liberal Party in Britain, and it would encircle much of the world in the 20th century. In addition to examining negative and positive liberty, liberals have tried to understand the proper relationship between liberty and democracy. As they struggled to expand suffrage rights, liberals increasingly understood that people left out of the democratic decision-making process were liable to the tyranny of the majority, a concept explained in Mill’s On Liberty and in Democracy in America (1835) by Alexis de Tocqueville. As a response, liberals began demanding proper safeguards to thwart majorities in their attempts at suppressing the rights of minorities.

Besides liberty, liberals have developed several other principles important to the construction of their philosophical structure, such as equality, pluralism, and toleration. Highlighting the confusion over the first principle, Voltaire commented that “equality is at once the most natural and at times the most chimeral of things”. All forms of liberalism assume, in some basic sense, that individuals are equal.

In maintaining that people are naturally equal, liberals assume that they all possess the same right to liberty. In other words, no one is inherently entitled to enjoy the benefits of liberal society more than anyone else, and all people are equal subjects before the law.

Beyond this basic conception, liberal theorists diverge on their understanding of equality. American philosopher John Rawls emphasized the need to ensure not only equality under the law, but also the equal distribution of material resources that individuals required to develop their aspirations in life. Libertarian thinker Robert Nozick disagreed with Rawls, championing the former version of Lockean equality instead.

To contribute to the development of liberty, liberals also have promoted concepts like pluralism and toleration. By pluralism, liberals refer to the proliferation of opinions and beliefs that characterize a stable social order. Unlike many of their competitors and predecessors, liberals do not seek conformity and homogeneity in the way that people think; in fact, their efforts have been geared towards establishing a governing framework that harmonizes and minimizes conflicting views, but still allows those views to exist and flourish.

For liberal philosophy, pluralism leads easily to toleration. Since individuals will hold diverging viewpoints, liberals argue, they ought to uphold and respect the right of one another to disagree. From the liberal perspective, toleration was initially connected to religious toleration, with Spinoza condemning “the stupidity of religious persecution and ideological wars”. Toleration also played a central role in the ideas of Kant and John Stuart Mill. Both thinkers believed that society will contain different conceptions of a good ethical life and that people should be allowed to make their own choices without interference from the state or other individuals.

Era of enlightenment

The development of liberalism continued throughout the 18th century with the burgeoning Enlightenment ideals of the era. This was a period of profound intellectual vitality that questioned old traditions and influenced several European monarchies throughout the 18th century. In contrast to England, the French experience in the 18th century was characterized by the perpetuation of feudal payments and rights and absolutism. Ideas that challenged the status quo were often harshly repressed. Most of the philosophes of the French Enlightenment were progressive in the liberal sense and advocated the reform of the French system of government along more constitutional and liberal lines.

Baron de Montesquieu wrote a series of highly influential works in the early 18th century, including Persian Letters (1717) and The Spirit of the Laws (1748). The latter exerted tremendous influence, both inside and outside of France.

Montesquieu pleaded in favor of a constitutional system of government, the preservation of civil liberties and the law, and the idea that political institutions ought to reflect the social and geographical aspects of each community. In particular, he argued that political liberty required the separation of the powers of government.

Building on John Locke’s Second Treatise of Government, he advocated that the executive, legislative, and judicial functions of government should be assigned to different bodies. He also emphasized the importance of a robust due process in law, including the right to a fair trial, the presumption of innocence and proportionality in the severity of punishment.

Another important figure of the French Enlightenment was Voltaire. Initially believing in the constructive role an enlightened monarch could play in improving the welfare of the people, he eventually came to a new conclusion: “It is up to us to cultivate our garden”. His most polemical and ferocious attacks on intolerance and religious persecutions began to appear a few years later. Despite much persecution, Voltaire remained a courageous polemicist who indefatigably fought for civil rights—the right to a fair trial and freedom of religion—and who denounced the hypocrisies and injustices of the Ancien Régime.

By this time the single Jewish causers ought to have taken note that even well-known pro-white bloggers, who are either Christians or married to Christians, are openly saying that the root causes of our predicament are to be found in our most cherished traditions: religion and the ideals of secular liberalism.

The following are a couple of passages from “Death to Modernity—American Perspectives.” Alex Kurtagic responds to what some angry Christian commenters had said (in italics):

1.-

Saying that Christianity started liberalism is like saying the existence of truth is to blame for the distortion thereof.

Tracing the roots of an ideology to a religion’s metaphysics is not the same as blaming the ideology on the religion, or saying that the religion ‘started’ the ideology. The American Constitution and the Declaration of Independence (Introduction and Preamble) also have roots in Christianity, yet no one would reasonably ‘blame’ the American Constitution and the Declaration of Independence on Christianity or claim that Christianity ‘started’ them. Though known for their pagan outlook and critiques of Christianity, in the Manifesto the ENR merely points out the irony of Christian metaphysics’ having supplied—without that having been the intention—liberal theorists with the means to ‘liberate’ the individual from Christianity (along with anything transcendent or external to the individual).

Tracing the roots of an ideology to a religion’s metaphysics is not the same as blaming the ideology on the religion, or saying that the religion ‘started’ the ideology. The American Constitution and the Declaration of Independence (Introduction and Preamble) also have roots in Christianity, yet no one would reasonably ‘blame’ the American Constitution and the Declaration of Independence on Christianity or claim that Christianity ‘started’ them. Though known for their pagan outlook and critiques of Christianity, in the Manifesto the ENR merely points out the irony of Christian metaphysics’ having supplied—without that having been the intention—liberal theorists with the means to ‘liberate’ the individual from Christianity (along with anything transcendent or external to the individual).

2.-

What a crock!—blaming the evils of liberalism and the Leftist destruction of the U.S.A. on true Christianity. Liberalism sprang from secularism and both are ‘Jewish’ in origin.

Prior to emancipation, Jews were confined to ghettos and lived under civic and legal restrictions in Europe. By the time Jewish emancipation began in the 1790s, the Enlightenment (associated with secularism) was already in decline and giving way to Romanticism and the Counter-Enlightenment. In most places of Europe, Jews were not emancipated until the mid-1800s. On the other hand, Liberalism, like the Enlightenment, dates back to the 1600s. John Locke’s Two Treatises of Government was published in 1689, over a century before the first Jewish emancipation. Of the thinkers we associate with classical liberalism or the Enlightenment—John Locke, René Descartes, Isaac Newton, Montesquieu, Adam Smith, Thomas Malthus, David Hume, Jeremy Bentham, Voltaire, John Stuart Mill, David Ricardo, and Baruch Spinoza—only Ricardo and Spinoza were Jews, but both were disowned. The rest were Christians.

What we can say is that many Jews since emancipation have seen the obvious benefit to Jews generally of their host societies being as secular as possible, and have accordingly campaigned in various ways to accelerate and maximise a process of secularisation that had already been begun by lapsed, indifferent, or apostate Christians. The idea of separation of Church and state is not Jewish, but, as Henry Ford describes in The International Jew, Jewish activists—who, obviously, were either preoccupied with real or perceived anti-Semitism or who wished to advance the interests of their ethnic group—used this idea to further their aim of removing Christianity from the public square.

Liberalism does not reject Christianity or religion tout court; indeed, the Founding Fathers of the United States, though liberals to a man, were Christians—not anti-Christian atheists, like the Marxists who subsequently critiqued liberalism—and conceived the United States as a Christian country intended for Christians. What liberalism attempts to do is to ‘liberate’ the individual from anything transcendent or outside of the individual. The existence and the will of God is then ascertained by rational means, and the process of ascertaining is left to the individual, who becomes the measure of all things. Dogmatic belief and subservience to tradition and authority are abandoned.

One must not conflate anti-Western Jewish intellectual movements with liberalism just because the former marshalled liberal ideas to serve Jewish ethnic aims. The abovementioned Jewish movements were of a liberal character because they originated in a liberal context. Had they originated in a non-liberal context, we would have seen Jewish movements of a very different kind. That these movements remain influential highlights the dominance of liberalism and the need to dismantle it, for, once dismantled, these movements will become unthinkable. And depending on what replaces liberalism, ethnic subversion, Jewish or otherwise, may or may not become more difficult. Ultimately, it depends on how we reshape the intellectual landscape—nothing is predetermined or guaranteed.

♣

And this is Hunter Wallace’s latest entry at

Occidental Dissent, “Derb on Ethnomasochism”:

Derb is trying to understand the roots of White ethnomasochism at VDARE and Takimag.

Seeing as how this is a historical inquiry and intersects our particular fixation on the American South, we can unequivocally say that evangelical Christianity and Enlightenment ideology are the roots of this phenomena, and that the anti-slavery movement was its first major flowering.

It doesn’t take much time wandering through what Europeans were doing in the Caribbean in the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries to figure out that they were operating in another moral universe.

By the late eighteenth century/early nineteenth century, you have your Abbé Raynals and John Browns who are fine specimens of this deranged type.

If I had artistic skills, I would draw a cartoon of a tree labeled “anti-slavery” with fruit hanging from its branches labeled “anti-racism” and “civil rights” and “feminism” and “free love” and “white guilt” and “communism” and “decolonization” and “white genocide.”