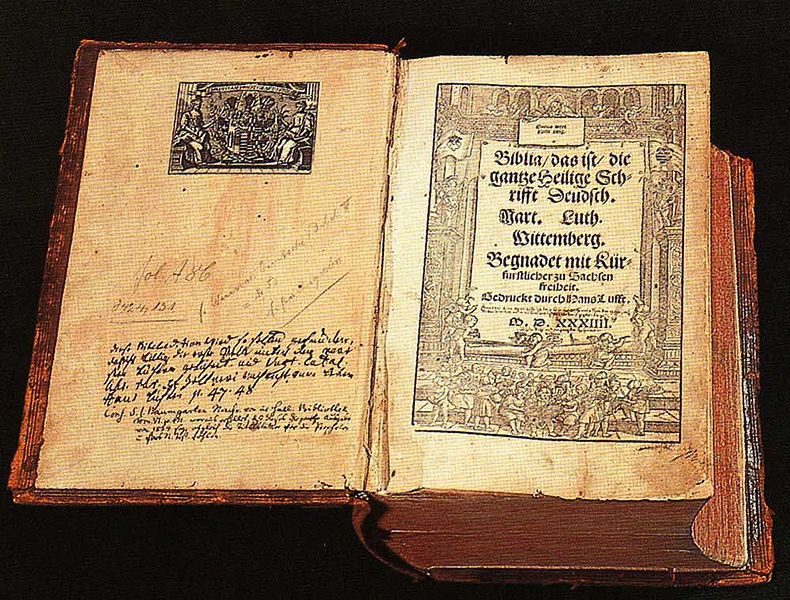

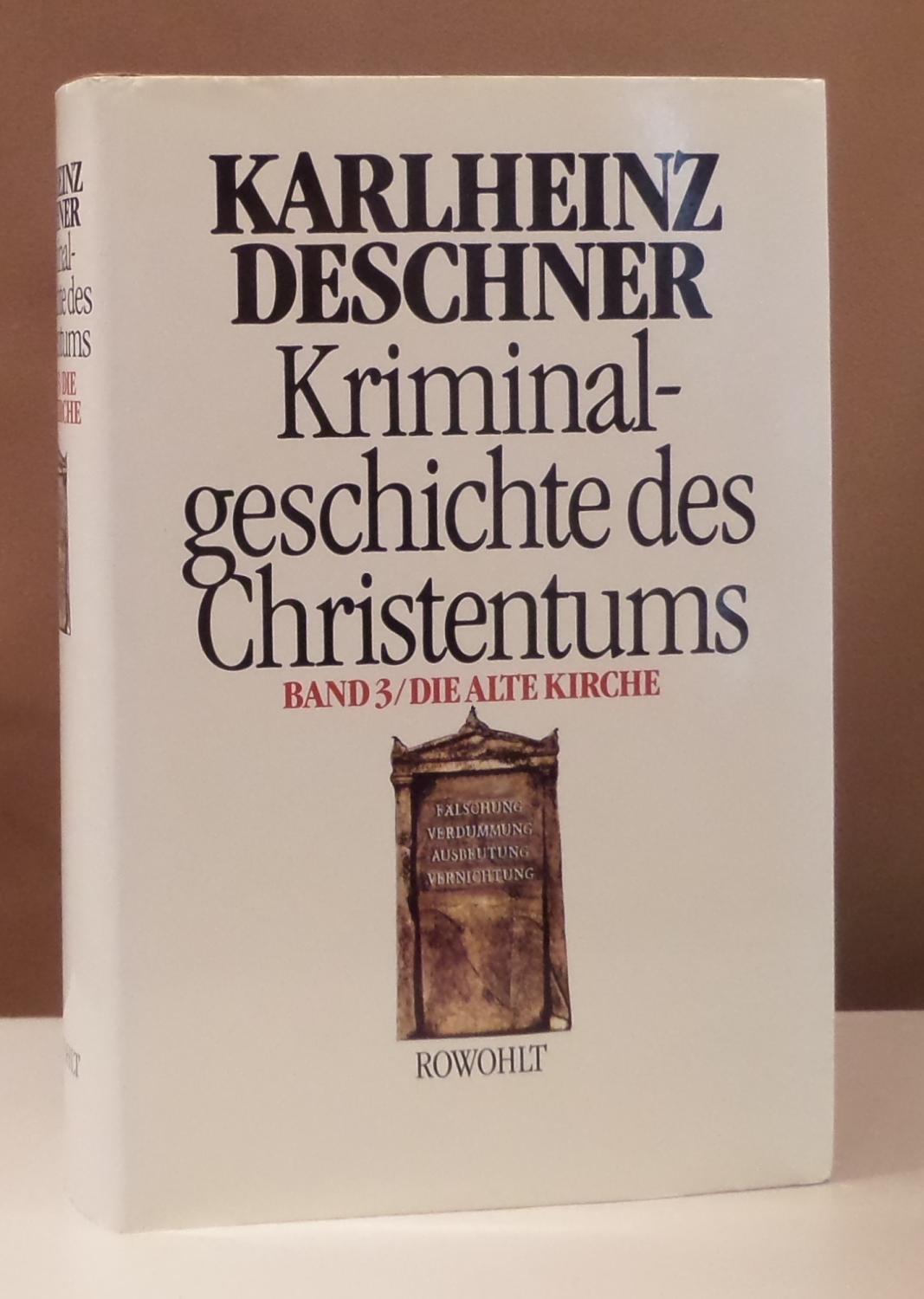

Below, a translation from a section of the third volume of

Karlheinz Deschner’s Kriminalgeschichte des Christentums.

The five books of Moses, which Moses did not write

The Old Testament is a very random and very fragmentary selection of what was left of ancient transmission. The Bible itself quotes the titles of nineteen works that have been lost, among them The Book of the Wars of the Lord, The Story of the Prophet Iddo, The Book of the Good. However, the researchers believe that there were many other biblical texts that have not left us even the title. Have they also been holy, inspired and divine?

In any case the remains are enough, more than enough; especially of the so-called five books of Moses, presumably the oldest and most venerable, that is, the Torah, the Pentateuch (Greek pentáteuchos, the book ‘containing five’ because it consists of five rolls): a qualifier applied around 200 AD by Gnostic writers and Christians. Until the 16th century, it was unanimously believed that these texts were the oldest of the Old Testament and that they would therefore be counted among the first in a chronologically ordered Bible. That is something that today cannot even be considered. The Genesis, the first book, is without good reason at the head of this collection. And although still in the 19th century renowned biblical scholars believed they could reconstruct an ‘archetype’ of the Bible, an authentic original text, that opinion has been abandoned. Or even worse, ‘it is very likely that such an original text never existed’ (Comfeld / Botterweck).

The Old Testament was transmitted mostly anonymously, but the Pentateuch is attributed to Moses and the Christian churches have proclaimed his authorship until the 20th century. However, while the patriarchs Abraham, Isaac and Jacob, the first Israelite fathers, must have lived between the 21st and the 15th centuries BC, or between 2000 and 1700 if they actually lived, Moses—‘a marshal, but at the bottom of his being with a rich emotional life’ (Cardinal Faulhaber)—must have lived in the 14th or 12th century BC, if he also lived.

In any case, nowhere outside the Bible the existence of these venerable figures, and others more recent, is ‘documented’. There is no proof of their existence. Nowhere have they left historical traces; neither in stone, bronze, rolls of papyrus, nor in tablets or cylinders of clay, even though they are more recent than, for example, many of the Egyptian sovereigns historically documented in the form of famous tombs, hieroglyphs or cuneiform texts: authentic certificates of life. Therefore, writes Ernest Garden, ‘either one is tempted to deny the existence of the great figures of the Bible or, in case of wishing to admit their historicity even with the lack of demonstrative material, it is supposed that their life and time they passed in the way described by the Bible… had circulated for many generations’.

For Judaism, Moses is the most important figure in the Old Testament. It is mentioned 750 times as a legislator; the New Testament does it 80 times. It is claimed that all the Laws were being handled as if Moses had received them at Sinai. In this way he acquired for Israel a ‘transcendental importance’ (Brockington). Each time he was increasingly glorified. He was considered the inspired author of the Pentateuch. It was attributed to him, the murderer (of an Egyptian because he had beaten a Hebrew), even a pre-existence. He became the forerunner of the Messiah, and the Messiah was considered a second Moses. Many legends about him emerged in the 1st century BC; a novel about Moses, and also a multitude of artistic representations. But the tomb of Moses is not known. In fact, the prophets of the Old Testament quote him five times.

Ezekiel never mentions him! And yet, these prophets evoke the time of Moses, but not him. In their ethical-religious proclamations they never rely on Moses. Neither the papyrus Salt 124 ‘has a testimony of any Moses’ (Cornelius). Nor does archaeology give any sign of Moses. The Syrian-Palestinian inscriptions barely quote him in as little measure as cuneiform texts or hieroglyphic and hieratic texts. Herodotus (5th century BC) knows nothing of Moses. In short, there is no non-Israelite proof of Moses, our only source of his existence is—as in the case of Jesus—the Bible.

There were already some who in Antiquity and in the Middle Ages doubted the unity and authorship of Moses in the Pentateuch. It was hardly believed that Moses himself could have reported on his own death, ‘an extraordinary question’ Shelley mocks, ‘almost as how to describe the creation of the world’ in Genesis. However, a deep criticism only came from the pen of Christian ‘heretics’, as the primitive Church saw no contradiction in the Old or New Testaments.

In the modern age Andreas Karlstadt was one of the first scholars in which some doubts were aroused when reading the Bible (1520). More doubts were raised by the Dutchman Andreas Masius, a Catholic jurist (1574). But if this pair, and shortly afterwards the Jesuits B. Pereira and J. Bonfrère, only declared some citations as post-Mosaic and continued to consider Moses the author of the whole text, the English philosopher Thomas Hobbes declared that some paragraphs of the Pentateuch were Mosaics but post-Mosaic most of the text (Leviathan, 1651). In 1655 the reformed French writer I. de Peyrère went even further; and in 1670, in his Tractatus Theologico-Politicus Spinoza denied Mosaic authorship for the whole thing.

In the 20th century some scholars of religion, among them Eduard Meyer (‘it is not the mission of historical research to invent novels’), and Danek of the school of the Prague, have questioned the historical existence of Moses himself; but their adversaries have rejected such hypothesis.

It is curious that even the most illustrious minds, the greatest sceptics and scientists under whose daring intervention the sources of material are shelled so that there is little space left for the figure of Moses, present us again, as if by sleight of hand, Moses in all his greatness as the dominant figure of all Israelite history. Although everything around this character is too colourful or too obscure, the hero himself cannot be fictional they say. As much as the criticism of sources has reduced the historical value of these books, almost annulled it, ‘there remains a broad field of the possible’ (Jaspers). It is not surprising, then, that among some conservatives Moses is of greater importance than the Bible!

In short: after Auschwitz, Christian theology returns to win over the Jews. ‘Today again a more positive idea of ancient Israel and its religion is possible’. However, Moses is still ‘a problem’ for the researchers, ‘there is no light to illuminate his figure’ and the corresponding traditions remain ‘outside the capacity of historical control’ according to the Bibl. Hist. Handwörterbuch (Hist. Bibl. handwritten book). Although these scholars strongly refuse to ‘reduce Moses to a nebulous figure, known only to legends’, they admit at the same time that ‘Moses himself is faded’. They claim that ‘the uniqueness of the Sinai event cannot be denied’ but they add immediately ‘although the historical demonstration is difficult’. They find in the ‘stories about Moses a considerable historical background’ and some paragraphs later claim that this ‘can not be proved by facts’, that ‘it cannot be witnessed by historical facts’ (Cornfeld / Botterweck).

This is the method followed by those who do not deny the evidence itself, but neither do they want everything to collapse with a crash (No way!). For M.A. Beek, for example, there is no doubt that the patriarchs are ‘historical figures’. Although he only sees them ‘on a semi-dark background’ he considers them ‘human beings of great importance’. He himself admits: ‘To date we have not been able to find documentary evidence of the figure of Joshua in Egyptian literature’. He adds that, apart from the Bible, he does not know ‘a single document containing a clear and historically reliable reference to Moses’. And he continues that, if we do without the Bible, ‘no source is known about the expulsion from Egypt’. ‘The abundant literature of the Egyptian historiographers silences, with a worrying obstinacy, events that should have deeply impressed the Egyptians, if the account of the Exodus is based on facts’. Beek is also surprised that the Old Testament rejects

curiously enough, any data that would make possible a chronological fixation of the departure from Egypt. We do not see the name of the Pharaoh that Joshua knew, nor the one who oppressed Israel. This is all the more amazing because the Bible retains many other Egyptian names of people, places and offices.

Even more suspicious than the lack of chronological reference points in the Old Testament is the fact that none of the known Egyptian texts cites a catastrophe that affected a Pharaoh and his army while chasing the fleeing Semites. Since historical documents have an abundance of material on the epoch in question, at least some allusion would be expected. The silence of the Egyptian documents cannot be dismissed with the observation that court historiographers do not usually talk about defeats, since the events described in the Bible are too decisive for Egyptian historians to have overlooked them.

‘It is really curious’, this scholar continues, ‘that no tomb of Moses is known’. Thus, ‘the only proof of the historical truth of Moses’ is for him ‘the mention of a great-grandson in a later epoch’.

‘And Moses was 120 years old when he died’ says the Bible, although his eyes ‘had not weakened and his strength had not diminished’ and God himself buried him and ‘no one knows to this day where his tomb is’. A pretty weird end. According to Goethe, Moses committed suicide and according to Freud his own people killed him. The disputes were not rare, as with Aaron and Miriam. But as always, the closing of the fifth and last book of the Pentateuch significantly recalls ‘the acts of horror that Moses committed before the eyes of all Israel’. Every character always enters the history thanks to his terrifying feats, and this is so regardless if he lived or not really. But whatever the case may be with Moses, the investigation is divided.

The only thing that is clear today, as Spinoza saw it, is that the five books of Moses, which directly attribute to him the infallible word of God, do not come from him. This is the coincidental conclusion of the researchers.

Naturally, there are still enough people like Alois Stiefvater and enough little treatises such as Schlag-Wörter-Buch für katholische Christen types (Schlag Words Book for Catholic Christians) who continue to deceive the mass of believers by making them believe in the five books of Moses, that ‘although not all have been directly written by him, they are due to him’. How many, and which ones Moses wrote directly, Stiefvater and his accomplices do not dare to say. What remains true is that the Laws that were considered as written by the hand of Moses or even attributed to the ‘finger of God’ are also fabrications. (On the other hand, although God himself writes the Law on two tablets of stone, Moses had so little respect for them that in his anger against the golden calf he destroyed them.)

It is also clear that the writing of these five books was preceded by an oral transmission of many centuries, with constant changes. And then there were the editors, the authors, the biblical compilers who participated throughout many generations in the writing of the books by ‘Moses’, which is reflected in the different styles. It looks like a collection of different materials, such as the entire fourth book.

Thus arose a very diffuse collection lacking any systematic organisation, overflowing with motifs of widely spread legends, etiological and folkloristic myths, contradictions and duplications (which by themselves alone exclude the writing by a single author). Added to all this is a multitude of heterogeneous opinions that have been developed in a gradual way, even in the most important issues. Thus the idea of the resurrection arises very little by little in the Old Testament, and in the books Ecclesiasticus, Ecclesiastes and Proverbs any testimony of beliefs in the resurrection is missing. In addition, the scribes and compilers have constantly modified, corrected and falsified the texts, which acquired new secondary extensions every time. And these processes went on for entire epochs.

The Decalogue or Ten Commandments, which Luther considered the supreme incarnation of the Old Testament, proceeds in its earliest form perhaps from the beginning of the age of kings. Many parts of the Pentateuch that must have been written by the man who lived, if he lived, in the 14th or 13th centuries BC—no less than sixty chapters of the second, third and fourth books—were not produced or collected by Jewish priests until the 5th century BC. Thus, the final redaction of the books awarded to Moses—I quote the Jesuit Norbert Lohfink—’took place some seven hundred years later’. And the composition of all the books of the Old Testament—I quote the Catholic Otto Stegmüller—was prolonged ‘for a period of approximately 1,200 years’.

Complete set of scrolls constituting the Hebrew Bible.

Research on the Old Testament has reached enormous dimensions and we cannot contemplate it here—saving the reader from the labyrinthic methodology: the ancient documentary hypotheses of the 18th century, the assumptions of fragments, complements, crystallisation and the important differentiation of a first Elohist, a second Elohist, a Jahwist or Yahwist (H. Hupfeld, 1835), the formal historical method (H. Gunkel, 1901), the various theories about the sources, the theory of two, three, four sources, the written sources of the ‘Jahwist’ (J), of the ‘Elohist’ (E), of the ‘writing of the priests’ (P), of ‘Deuteronomy’ (D), of the combined writing… We cannot get lost in all the threads of the story, the traditions, the plethora of additions, complements, inclusions, annexes, proliferations, textual modifications, the problem of the variants, the parallel versions, the duplications—in short, the enormous ‘secondary’ enlargement, and the history and the scrutiny of the texts. We cannot discuss either the reasons for the extension of the Pentateuch into a Hexateuch, Heptateuch or even Octateuch, or its limitation to a Tetrateuch however interesting these hypotheses may be within the context of our subject.

A simple overview of the critical comments, such as Martin Noth’s explanations of the Mosaic books, will show the reader its editors, redactors, compilers; of additions, extensions, later contributions, combinations of different states of incorporation, modifications, etc.: an old piece, an older one, a fairly recent one that is often called secondary, perhaps secondary, probably secondary, surely secondary. The word ‘secondary’ appears here in all conceivable associations. It seems to be a keyword, and even I would like to affirm without having made an exact analysis of its frequency: there is no other word that appears with greater assiduity in all these investigations of Noth and his work.

Recently Hans-Joachim Kraus has written Geschichte der historisch-kritischen Erforschung des Alten Testaments (The story of the historical-critical exploration of the Old Testament). Innovative and advanced for the 19th century was W.M.L. de Wette (died 1849) who perceived the many stories and traditions of these books and considered ‘David’, ‘Moses’ and ‘Solomon’ not as authors but as nominal symbols, such as collective names.

Due to the immense work of scholars in the course of the 19th century and the eventual debunking of biblical sacred history, Pope Leo XIII attempted to obstruct the freedom of research through his 1893 Encyclical Providentissimus Deus (The most provident God). A counteroffensive was opened also under his successor, Pius X, in a decree. From De Mosaica authentia Pentateuchi (Authentic Mosaic Pentateuch), June 27, 1906, Moses was considered an inspired author. Although on January 16, 1948 the secretary of the papal biblical commission declared in an official reply to Cardinal Suhard that the decisions of the commission ‘do not contradict with a later scientific analysis of these questions’, in Roman Catholicism ‘true’ always means: in the sense of Roman Catholicism. The final exhortation should be understood along the same lines: ‘That is why we invite Catholic scholars to study these problems from an impartial point of view, in the light of sound criticism’. But ‘from an impartial point of view’ means: from a partial point of view for the interests of the papacy. And with ‘sound criticism’ it is not meant to say anything other than a critique in favour of Rome.

The historical-scientific analysis of the writings of the Old Testament certainly did not provide a sure verdict about when the texts arose, although in some parts, as for example in the prophetic literature, the certainly about their antiquity is greater than, say, the religious lyrics. When it comes to the age of the Laws, there is less certainty. But historical-religious research with respect to the Tetrateuch (Moses 1-4) and the Deuteronomic historical work (Moses 5, Joshua, Judges, books of Samuel and the Kings) speaks of ‘epic works’, ‘mythological tales’, ‘legends’ and ‘myths’ (Nielsen).

The confusion that reigns in scholarship is manifest in the abundance of the repetitions: a double account of Creation, a double genealogy of Adam, a universal double flood (in one version the flood subsides after 150 days; according to other it lasts one year and ten days; and according to another, after raining forty days there are added another three weeks), in which Noah—then 600-years-old according to Genesis 7:6—took in the Ark seven pairs of pure animals and one of impure ones and, according to Genesis 6, 19 and 7, 16, there were a pair of pure and impure animals. But we would be very busy telling all the contradictions, inaccuracies, deviations with respect to a book inspired by God, in which there are a total of 250,000 textual variants.

In addition, the five books of Moses know a double Decalogue; a repeating legislation on slaves, the Passah, a loan, a double on the Sabbath, twice the entry of Noah into the Ark, twice the expulsion of Hagar by Abraham, twice the miracle of the manna and the quails, the election of Moses; three times the sins against the body and life, five times the catalogue of festivals, and are at least five legislations about the tenths, etc.

______ 卐 ______

Liked it? Take a second to support this site.

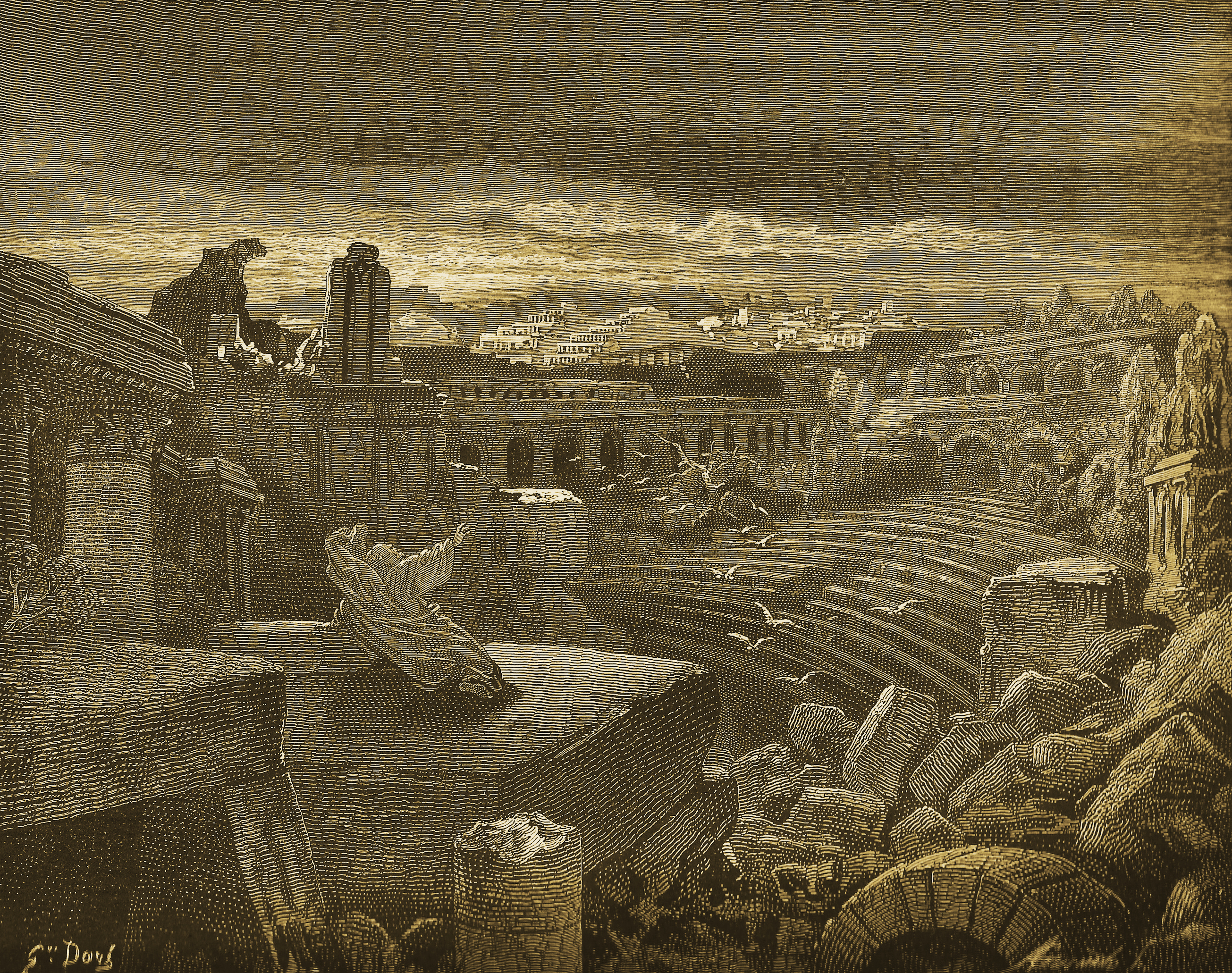

(Note of the editor: As in all art that Christian painters have produced throughout the centuries, in this engraving of Judgement of Solomon by Gustave Doré the characters have been completely Aryanised. If machines to see the past could be invented, white nationalists would be shocked to see the Semitic physiognomy of the main characters of the Bible, if they even existed.)

(Note of the editor: As in all art that Christian painters have produced throughout the centuries, in this engraving of Judgement of Solomon by Gustave Doré the characters have been completely Aryanised. If machines to see the past could be invented, white nationalists would be shocked to see the Semitic physiognomy of the main characters of the Bible, if they even existed.)