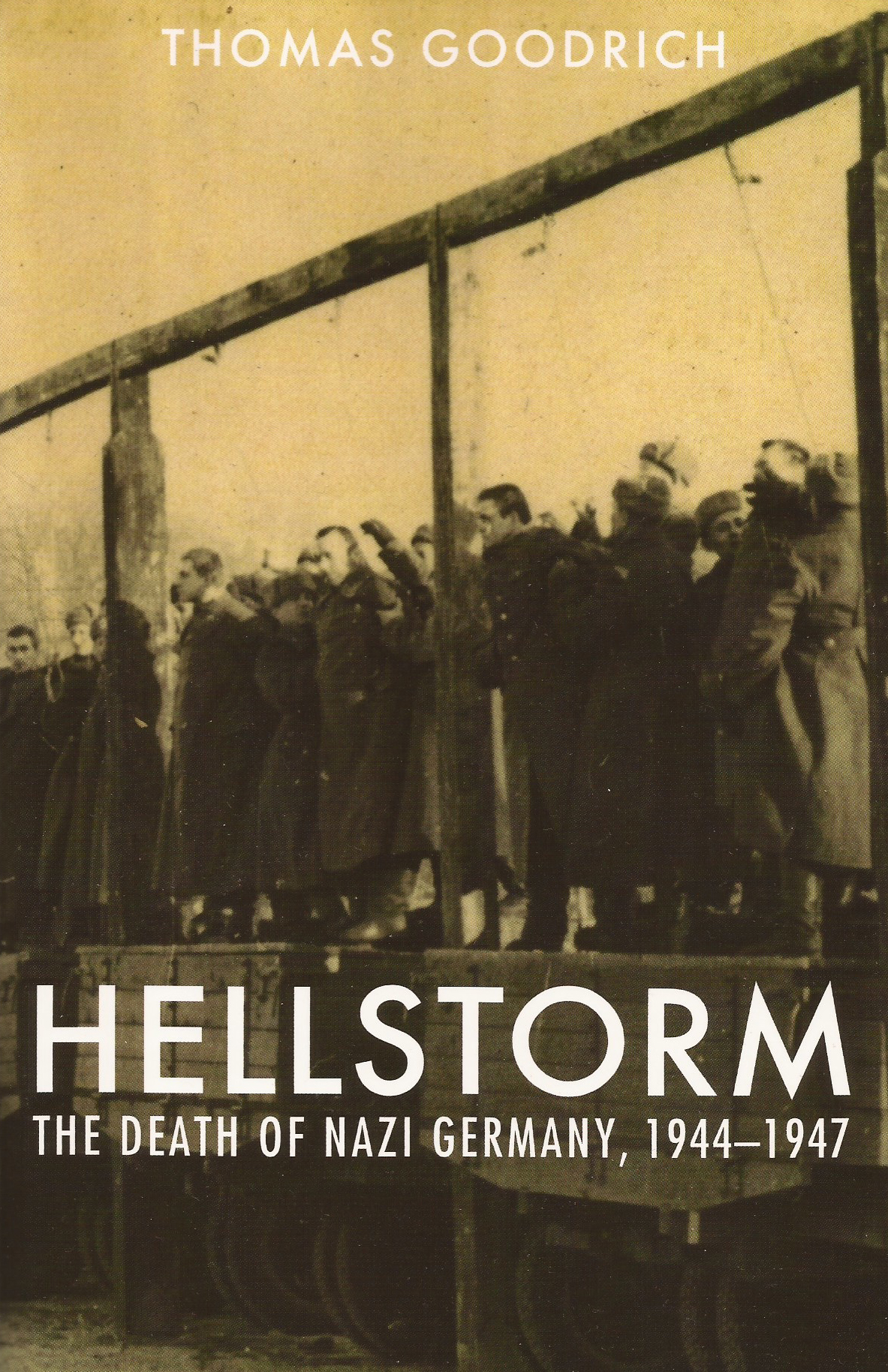

German-American Bund camp

1936-1941

German-American Bund

At its height, the Friends of the New Germany had approximately 10,000 members. This is ten times the number of members that Gau-USA had, and twenty times the number of its predecessor, Teutonia. However, sixty percent of FDND members were German citizens, not eligible for membership in the newly reorganized Bund. In a sense, Kuhn had to rebuild the Bund from the ground up.

Fritz Julius Kuhn was born in Munich in 1896. He served as an infantry lieutenant during the First World War, and had earned the Iron Cross Second Class. Kuhn and his wife Elsa emigrated to Mexico in 1923. They moved to the US in 1927, and Kuhn became a naturalized citizen in 1933. He settled in Detroit and was employed as a chemist by the Ford Motor Corporation. He took an active interest in ethnic politics, and became the leader of the Detroit chapter of the FDND.

A minor point, but one that is worth addressing: Kuhn’s title was Bundesleiter. Historians and biographers, however, in error frequently refer to him as BundesFüher. But Kuhn himself was quick to point out that there was only one Füher, and that was Adolf Hitler.

Under his determined and energetic leadership, the Bund grew steadily. By the time it ceased operations in December 1941, the Bund had an organized presence in 47 of the 48 states (the exception being Louisiana), with a combined 163 local chapters. A fully accredited chapter was known as a ‘unit’. As a minimum requirement, each unit had a unit leader, a treasurer, a public relations officer and a nine-man OD squad. Many units had a membership of over a hundred. Chapters that could not meet the minimum requirements were known as ‘branches’, and were attached to the nearest unit.

The Bund was divided into three departments – Eastern, Midwestern and Western – which in turn were divided into regions. The regions were subdivided into state organizations, which were further organized by city, neighbourhood, and even block-by-block where the membership warranted it. Total membership is unknown, but probably exceeded 25,000. The uniformed Order Division had an estimated 3,000 members nationwide.

The Bund published a weekly newspaper, with both German-language and English content. It was initially called the Deutscher Weckruf und Beobachter (‘German Wake-Up Call and Observer’). By 1937, it had a total circulation of 20,000. Three regional editions were published that carried local news and advertisements. In 1939, as part of an ongoing effort to Americanize the Bund, its full name was lengthened to Deutscher Weckruf und Beobachter and Free American. From that point on, for convenience’s sake, it was normally referred to simply as the Free American. Building on its success, the Bund published several other publications, including a youth magazine.

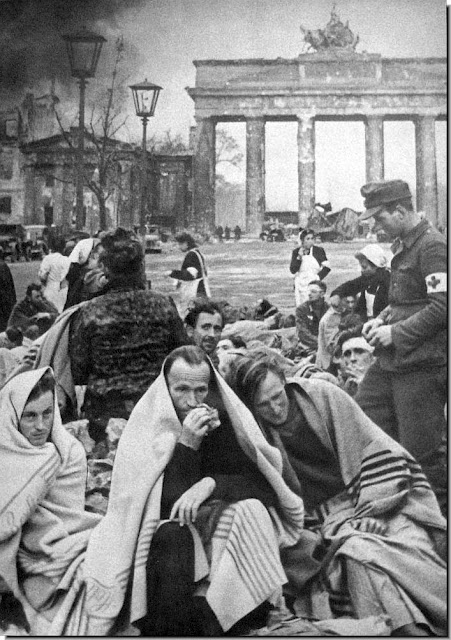

A notable Bund feature were its summer camps, which were located on Bund-owned property. There were 18 of these camps in all. Some were modest in size, but others, like Camp Nordland in New Jersey, Camp Siegfried on New York’s Long Island and Camp Hindenburg in Wisconsin, were large and elaborate, with facilities for year-round living. Camp activities included hiking, camping, swimming and other athletics. There were also communal cultural activities. Special programs were developed for young people, designed to build comradeship and to strengthen bodies, minds and character.

______ 卐 ______

Editor’s note: Could one imagine this in today’s US? They wouldn’t even let them protest against a historic statue that the government removed in Charlottesville! One of the biggest lies of the American system is that it claims to allow freedom of speech and association. As we will see in the subsequent history of the Bund, it allows neither. The American system has ways of destroying dissidents through legal and paralegal system of penalties, as we shall see not only in the destruction of the Bund but of the pro-Aryan groups that followed it.

______ 卐 ______

The Bund was not a political organization in the normal sense of the word, and did not run candidates for office. It did, however, hold public meetings and parades, and these gatherings became a target for protests by Communists and Jews. Sometimes the protestors would physically attack the Bund members, resulting in bloody brawls. Clashes between uniformed National Socialists and their enemies received generous publicity in the mainstream media, which was eager to portray the ‘Bundists’ (as they termed the Bund members) as violent troublemakers. Back in Germany, the NSDAP viewed such publicity as detrimental to the foreign policy interests of the Reich. The same concerns that Hitler and Hess had over Gau-USA and the Friends of the New Germany had not gone away: instead, they were taking place on a larger scale and with increased media scrutiny.

The Bund’s 1936 trip to Germany

Nearly all Bund activity took place on a local level, but on at least two occasions, the Bund pooled its resources for a major national event. The first of these was an excursion to Hitler’s Germany in the summer of 1936. The second was a mass rally in New York City’s Madison Square Garden in February 1939.

The year 1936 was a watershed for Hitler’s Germany. When the National Socialists assumed power in early 1933, the country was in a dreadful condition as a result of the lost world war and fifteen years of democratic incompetence and corruption. It had been ravaged by the Great Depression and the depredations of the Treaty of Versailles. The economy was a wreck, unemployment was at a record high; many thousands of the most energetic and skilful Germans emigrated each year to seek a better life elsewhere. The media was in the hands of the Jews, as were other important segments of society. But after only three years of National Socialism, the Reich had been reborn: hunger had been banished, the economy was booming and the armed forces had been reorganized and strengthened. A new sense of optimism and national pride filled the population.

The 1936 Summer Olympics, held in Berlin, brought countless guests and tourists to the new Germany. Among those visitors were Fritz Kuhn and some 50 members of the newly-formed Bund. The American National Socialists toured the country, and were widely feted as heroes. Uniformed members of the OD were accorded the same privilege as the German SA and allowed to ride public transportation for free. In Munich, uniformed Bund members marched with the SA, the SS and the Hitler Youth in a parade.

Shortly before the beginning of the second parade in Berlin, Bundesleiter Kuhn and his officers were granted a short, formal audience with Hitler. This meeting is what today might be termed a ‘photo-op’ – the Füher shook hands with them and chatted amiably for a few minutes. One photograph from the occasion shows Hitler and Kuhn talking together. As the brief audience wrapped up, Hitler told Kuhn, ‘Go back and continue the struggle over there’. Nothing deep or significant was meant by these words: they were just a courtesy by the Füher to his American followers.

Upon his return to the United States, Kuhn lost no time in misrepresenting his brief photo-op with Hitler. Kuhn told reporters, ‘I have a special arrangement with the Füher’ to build the NS movement in America. Rumours spread that there had been a second, private meeting between Chancellor Hitler and the Bundesleiter, during which Hitler had given Kuhn detailed instructions on strengthening Germany’s position in the New World. Kuhn did nothing to stop the spread of such tall tales, and instead maintained that he had received a direct mandate from Hitler to lead the American movement.

Kuhn’s dishonesty and false claims undoubtedly strengthened his position as the undisputed leader of the Bund. They came at a steep cost, however, because now they lent credibility to the charges made by the Jews and other anti-German forces that Hitler harboured aggressive aims towards America. The foreign-born Kuhn, with his thick German accent and mannerisms that some felt were off-putting, became the public face of domestic National Socialism to ordinary citizens. It was a face that many found hostile and threatening. Instead of building support and sympathy for the New Germany, Kuhn had alienated a huge swath of the American population.

What Hitler and the NSDAP wanted from German-Americans

Hitler had low respect for groups or parties in other countries that wanted to imitate the NSDAP. He realized that such copycat groups were inorganic and essentially foreign to their folk. This included not just the Bund, but also NS parties such as those in Denmark and Sweden. He commented that if Sir Oswald Mosley were really a great man as he presented himself he would have come up with an original movement of his own, instead of merely aping the NSDAP and Mussolini’s Fascists.

But this does not mean that he felt that there was no way for Germans outside the Reich in foreign countries to help build National Socialism. Regarding the US, the Füher felt that there were two primary ways that indigenous American National Socialists could help the New Germany:

1. Those German-Americans and expatriate German nationals residing in the US could most effectively help out by relocating to Germany. There they could help build National Socialism first-hand in the Fatherland.

And, in fact, many did exactly this. An agency was set up to encourage and assist with their relocation, the Deutsches Auslands Institut (German Foreign Institute). It was headed by Fritz Gissibl, former leader of Teutonia and the FDND, provided financial assistance to Germans who wanted to return to their Fatherland, and it helped them reintegrate into German society. In this connection, an association was formed for German-Americans who had returned, called Kameradschaft-USA.

2. For those German-Americans unable or unwilling to relocate to Germany, there was still an important task that they could perform. Since the earliest days of the Hitler government, Germany had been faced with an international economic boycott of German goods by the Jews and their many allies. This hampered the economic recovery and financial growth of the Reich. By working to weaken the boycott and promote German imports, pro-NS Americans could render immediate and tangible aid to the Movement.

Fritz Kuhn formed a corporation to organize an NS fightback against the boycott, first called the Deutsch-Amerikaner Wirstschafts Anschluss (German-American Protective Alliance), and later renamed theDeutscher Konsum Verband (German Business League). The DKV urged American merchants to ignore the Jewish boycott and to buy German goods for resale. It also encouraged American consumers to buy goods made in Germany. The DKV held a highly publicized ‘Christmas Fair’ highlighting German-made products and promoting their sale.

The DAI and the DAWA/DKV had the full and enthusiastic support of Hitler and the NSDAP. Uniformed marches, provocative speeches and confrontational meetings, however, were the mainstays of public Bund activity and did not meet with the approval of Reich authorities, who did whatever they could to discourage such activities and to distance themselves from them – to no avail.

The Madison Square Garden rally

On February 20, 1939, the Bund held a mammoth rally in New York’s Madison Square Garden. The event was billed as a ‘Mass Demonstration for True Americanism’. It took place in proximity to George Washington’s birthday, and indeed, a gigantic image of the first president formed a backdrop for the speaker’s platform. Over 22,000 Bund members and allies gathered for the occasion, easily making it the largest National Socialist meeting ever held in North America, before or since. Some 1,200 OD men under the command of August Klapprott provided security. Outside the Garden, 80,000 unruly anti-Bund protestors scuffled with the police in an unsuccessful effort to disrupt the meeting.

______ 卐 ______

Editor’s note: Eighty thousand? The anti-NS sentiment in America isn’t just a thing of our times! Incidentally, red emphasis below, of Kerr’s text, is mine. I just want to show that since the beginning of the American racialist movements, they never stopped worshiping the Jewish god:

______ 卐 ______

Among the speakers were National Secretary James Wheeler Hill, National Public Relations Director Gerhard Wilhelm Kunze and Bundesleiter Kuhn. As Kuhn began his address, a Jew named Isadore Greenbaum pushed his way past the police, slipped between two OD guards, and rushed the stage. He was armed with a knife. The would-be assassin was quickly tackled by the OD and beaten into submission. Klapprott pulled his men off the Jew before he was badly hurt, and he was turned over to the police for arrest. Kuhn continued speaking without interruption. Later, some members and followers leaving the meeting were assaulted by the mob outside.

The Bund portrayed the event as a huge victory. And indeed, it was an impressive tactical and logistical triumph. The Bund had shown that it could organize a successful mass meeting in the face of massive opposition.

But the reaction in Berlin was not so favourable. From the standpoint of the German government, this was exactly the type of publicity that they did not want.

Bund ideology and outreach

The Bund formally adhered to the National Socialist worldview as expressed in NS Germany. But there was a problem: the US was not Germany, and the social, economic, political and racial situation in America did not correspond to that of Germany. The program and exact policies of the NSDAP did not fit the American scene. Kuhn’s solution to the quandary was two-fold: the Bund adhered strictly to German National Socialism internally, but in terms of public outreach it advocated an ideology that was an awkward fusion of National Socialism and the Christian Nationalism of the times. ‘Christian Nationalism’ was roughly equivalent to modern White Nationalism. It was not a religious movement, per se; rather, by ‘Christian’ it was understood that Jews were excluded. An example of this was a statement by Kuhn quoted in the New York Times:’ I am a White Man and I give the White Man’s salute: Heil Hitler!’

Publicly, the Bund claimed to be for ‘100 percent Americanism’ and opposed to ‘Jewish communism’. It never attempted to forge a specific American National Socialism, unique to the experiences and situation of the Aryan race in North America.

When it felt the need to give some intellectual heft to its outreach, the Bund would refer to the writings of Lawrence Dennis, who was the foremost American Fascist intellectual of the period, or to other non-Bund, non-NS theoreticians and commentators.

The German National Socialist Colin Ross attempted to provide some intellectual ballast for the Movement in America with his 1937 book, Unser Amerika (Our America). He gave lectures throughout the US which were supported and attended by Bund members. But in the end, he was an outsider, and it is unclear to what extent his work had any effect on the Movement in the US.

Decline and end of the Bund

The Madison Square Garden rally aggravated the increasing dissatisfaction of the German government with the Bund. The German ambassador, Hans Diekhoff, had a contentious relationship with the group. Public opinion, largely manufactured and manipulated by the Jews, was already strongly tilted against the Reich. The media wanted to portray the Bund as a violent, un-American subversive organization directly under Hitler’s command; every headline that played into that false image made Diekhoff’s already-challenging job that much more difficult. He sent repeated dispatches to Berlin urging the German government to sever all ties with the Bund and publicly disown it. But the truth was that there was little or nothing Berlin could do: Contrary to popular belief, the Bund was not under the command of Hitler, the German government, or the NSDAP. It was an independent organization that could conduct its operations in any way that it wished.

The average American had a negative appreciation of the Bund. It was widely assumed that the Bund was a ‘fifth column’, designed to aid the ‘Nazis’ if the Germans invaded the United States – which the media assured the public was Hitler’s ultimate aim.

Consequently, there was a widespread feeling that the government should ‘do something’ about the Bund. The Roosevelt regime was more than willing to comply, but there was a hitch: the Bund operated strictly within the limits of US law.

Eventually, the authorities found a solution: In May, 1939, Kuhn was charged with the embezzlement of approximately $14,000 of Bund funds. Kuhn had foolishly taken as a mistress Virginia Cogswell, a former beauty queen. He had purportedly used Bunds funds to pay for her medical bills and to ship some used furniture to her from California. The Bund hierarchy responded to the charges that Kuhn, as leader of the Bund, was free to use the money in question in any manner that he wanted to. But the government was out for blood, and in November Kuhn was convicted of misusing Bund funds. Eventually he was sent to New York’s Sing Sing prison.

The scandal, rocked the Bund, and resulted in many resignations. However, a new leader, Gerhard Wilhelm Kunze, stepped forward to lead the group until Kuhn was free again.

Bund operations continued until December 8, 1941 – the day after the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor, and three days before Hitler’s declaration of war against the United States. On that day the Bund national council voted to dissolve the organization, and it burnt sensitive documents before they could be seized by the FBI.

Other National Socialist and pro-NS groups

Although we have concentrated our attention on the German-American Bund, the Bund was not the only NS formation in the US during the pre-War period. We have previously mentioned the short-lived American National-Socialist Party of Anton Haegele (1935). In 1939, the Brooklyn chapter of the Bund – which was the largest in the nation – broke away and reformed the ANSP, under the leadership of Peter Stahrenberg. But, despite the excellence of its newspaper, the National American, the party was small and never amounted to anything.

Of the hundreds of other small groups that flourished during this period, the following are also worth mentioning:

• The Christian Mobilizers, a New York group led by Joseph ‘Nazi Joe’ McWilliams. Its uniformed branch was called the Christian Guard. Later, the group was renamed the American Destiny Party.

• The National Workers League, led by Russel Roberts, later a supporter and advisor of George Lincoln Rockwell. Based in Detroit.

• The Citizens Protective League, led by Kurt Mertig, later mentor to James Madole of the National Renaissance Party.

• American Nationalist Party (founded as the American Progressive Workers Party). Emory Burke, who would go on to be the founder of the post-War movement, was a member of this group.

Americans who were National Socialist or pro-NS also supported organizations such as Charles Lindbergh’s America First Committee, William Dudley Pelley’s Silver Shirt Legion, Father Charles Coughlin’s National Union for Social Justice, and the Christian Front.

To broaden its appeal, the Bund also held a unity rally with the Ku Klux Klan at August Klapprott’s Camp Nordland in 1940.