Mexican José Barba Martín, born in 1937, spent two decades studying philology in the United States. He earned a master’s degree in Romance languages at Tufts University, a doctorate in Romance languages at Boston College and, finally, a doctorate at Harvard University in Hispanic literature. Barba was one of the victims of the powerful Catholic paedophile Marcial Maciel. Decades after Maciel abused him, Barba, along with other victims, began a campaign to expose the abuses. Because of his persistent activism, he has been called ‘José Barba: the man who defied two popes’.

Yesterday I saw a video interviewing Barba where he said, at this point in the interview (my translation), that the abuses committed by Maciel were not only sexual, ‘that he did not abuse only through the body, but through the soul: through a system that will take over the psyche; from children, adolescents, young people until the moment when one is no longer master of one’s own words, and then not even of one’s thoughts’.

Barba is not an apostate from Christianity; just a critic of the Catholic Church, even critical of two popes—John Paul II and Benedict XVI—who protected paedophiles in the Church. But what strikes me about Barba is his almost complete lack of insight into his words I have just translated. Barba has failed to realise that the very teaching of the doctrine of eternal damnation, which comes right from the Gospels, is abusive to the souls of children. (Those who have seen the film Angela’s Ashes, or read the autobiographical memoir of the same title, remember that class in which a priest terrorises Irish children with horrific hellish imagery.)

Since I have spoken to Barba several times in Mexico City, I would like to add something to what I wrote about him in my January 2022 article, ‘On Alberto Athié’. As an autobiographer, I keep records of a few encounters with acquaintances. Little of my many diaries appear in my eleven autobiographical books. But from time to time I can exhume, from those diaries, some anecdotes for publication on this site.

On 30 March 2018 Barba came to my house and what I told about him in the article ‘About Alberto Athié’ happened. The following year, on 2 November 2019 to be exact, I met Barba in the café of the old Librería Gandhi that the intellectuals of the Mexican capital used to frequent (now the old bookstore is closed). Barba was talking, in Latin, to one of my chess-playing friends but when I sat down at their table they switched languages and spoke to me in Spanish. As the Gandhi Café closed relatively early, we then moved on to a restaurant.

Barba mentioned the book I had lent him the previous year when he visited my house, Summer 1945 by Tom Goodrich, but didn’t say a peep about its contents. Apparently, the erudite man didn’t experience the slightest cognitive dissonance with the holocaust perpetrated by the Allies, as narrated by Goodrich. Although he mentioned nothing of the book’s content, he commented, as a good thing, the impeachment of Donald Trump planned by the Democrats.

The Catholic Barba is a liberal philo-Semite even though he has no Jewish background, and that night he called Dutch politician Geert Wilders an ‘extremist’. When I pointed out that, according to the Jew Ron Unz, a whole constellation of conservative authors on the Second World War had been cancelled, Barba said that perhaps these authors had been victims of McCarthyism! (and recommended me a book on McCarthyism). I was flabbergasted. Unlike the chess-playing friend who accompanied us, Barba couldn’t even conceive that he had in front of him an Other ideologically speaking: someone who was reasoning from a completely different POV.

In the Gandhi Café, before going to the restaurant, I told Barba about Solzhenitsyn’s 200 Years Together; then, at the restaurant, I told him about the contents of the book. When I got home, I sent him an email with the link to 200 Years Together, as well as a link to Unz’s article.

On June 4, 2022, I saw my chess friend and Barba again, this time near the park where, as a young man, I used to play chess. I talked to him for a long time but I was shocked that, once again, Barba couldn’t conceive of the existence of a creature ideologically different from him. Barba is one of those old-fashioned men who believe that we younger people see them as repositories of ancestral wisdom. But I don’t see him that way. The religious manner in which he spoke to those present, without first inquiring whether they were atheists or not, could only mean that he was treating us as if we were his pupils. There was a moment when Barba mentioned the alleged deeds of Jesus’ apostles, and I replied that to me that was literary fiction.

Barba reacted by saying that this was extreme scepticism, and I was perplexed because Barba had read Misquoting Jesus: The Story Behind Who Changed the Bible and Why by Bart Ehrman. How could Barba have been unaware that the fundamentalist Christian Ehrman became an atheist after his New Testament research? The fact that Barba gave four copies of Ehrman’s book to his Catholic friends, in another occasion, gave the impression that he wanted to convince them of a more sceptical approach to the historical Jesus. But Barba not only swallowed the aforementioned story from Luke’s book as real history, he did something that puzzled me even more.

When I asked him if he was familiar with the field of critical NT studies that started in the Enlightenment, he said he was (Ehrman himself is part of that field). But Barba didn’t seem to realise that New Testament studies had moved several exegetes to lose faith since the seminal works of Reimarus, who flourished in the 18th century, and David Friedrich Strauss, who flourished in the 19th century. I could not believe that the very learned Barba, who reads the NT in the original Greek, would ignore facts relating to authors whose books he has given as presents!

And it is not a case of senility, for when I last saw him near the park of old chess friends, Barba was perfectly lucid. It is a matter of being locked in a theological bubble to the extent of being unable to hold a friendly discussion with the unbeliever in front of him. In ‘On Alberto Athié’ I omitted that Barba ignored my argument that women have less cranial mass than men—and that’s why, in chess, they compete against each other, parallel to the men’s tournaments so that men don’t massacre them in the science-game. Similarly, Barba ignored or didn’t know, that there are scholars who believe that the Acts of the Apostles is a religious novel rather than real history.

I could write pages and pages about my latest disagreement with Barba. But I don’t think I need to. Perhaps I will do so in the comments section if someone asks me for more detailed information about those disappointing meetings. What I am getting at is that scholarship is not wisdom and that someone can be highly respected in the media—like Barba—and yet be enclosed in such a bubble that he dissociates the existence of the dissenter in front of him. It is not that I want to convince Christians like Barba that the NT is fiction. It is simply the inability to communicate the fact that there are scholars who believe it is fiction that alarms me!

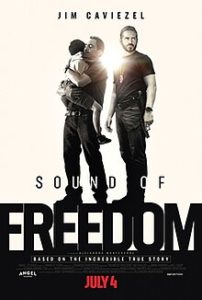

All this sheds light on what I was saying about the holocaust perpetrated by the Allies: something that normies, even when confronted, are unwilling to know as Barba did when I lent him, for a year, Goodrich’s book.

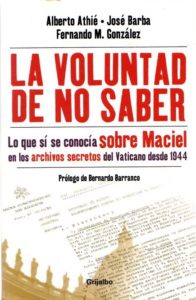

Alberto Athié, Barba and Fernando González wrote the book La voluntad de no saber: Lo que sí se conocía sobre Maciel en los archivos secretos del Vaticano desde 1944 (The Will Not to Know: What was Known about Maciel in the Vatican’s Secret Archives since 1944). Published in the context of Benedict XVI’s visit to Mexico, this book reveals the Vatican’s documents on the Maciel case demonstrating that, for more than sixty years, the highest authorities of the Catholic Church knew about the criminal conduct of the founder of the Legionaries of Christ.

But these guys have another kind of will not to know. They lack the will to know that several New Testament scholars say that the NT accounts are pure fiction, including the Acts of the Apostles, or that what the Establishment would have us believe about WW2 is rubbish. Likewise, millions of Westerners don’t want to know that the fact that we have different brains from women refutes feminism and the dogma of equality.

The way Barba treated me the few times I saw him is the way the normie treats the dissident: simply ignoring everything he says.