Or:

“The existence of Buddhism

should scare the White Nationalists

who can’t think of anything but Jews”

by Cesar Tort

In a previous post I talked about my golden rule: never read those authors or philosophers who write in obscure prose.

I confess that, in the past, when I was researching the pseudoscience called psychiatry, I had to read a book of one of those authors who deliberately and unnecessarily wrote in extremely opaque prose. I refer to Michel Foucault’s analysis of how the “mental health” movement was launched after an edict of Louis XIV that created, under the umbrella name of “General Hospital,” a prison in Paris for people who had not broken any law. While I found historical data in Foucault’s Madness and Civilization germane to my investigation, I also found much tasteless sludge in his text from a strictly literary, didactic viewpoint.

I mention this only to show that I can decipher opaque prose if I wish. But only in an exceptional case, where no other historical works on the same subject were available, I dared to break my rule.

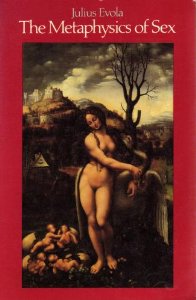

Such was not the case when I tried to read Julius Evola’s Metaphysics of Sex. After a few pages I realized that it was written deliberately in opaque prose and, since I was not researching the subject to write a book (as was the case of my study of psychiatry), my copy of Evola’s book ended in the trash can.

This illustrates my extreme passion for crystal-clear and distinct language, and my loathsome even for the great minds of Western thought that refuse to write in readable prose. In fact, what I liked the most in Leszek Kolakowski’s monumental, three-volume deconstruction of Marxism was the passage where he said that every metaphysical insight of Hegel had already been written before him, and in much clearer language. Kolakowski’s honest sentence contrasted sharply with Hans Küng’s dishonest appraisal of Hegel in a heavy treatise of my library that, to date, has escaped the trash can, The Incarnation of God: An Introduction to Hegel’s Theological Thought as Prolegomena to a Future Christology where Küng dishonestly claims that Hegel wrote his philosophy in pristine prose!

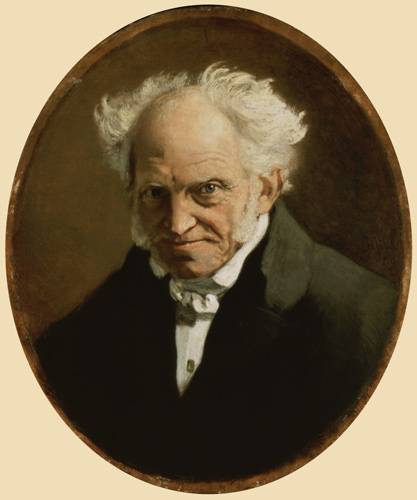

One of my favorite books is Matthew Stewart’s The Truth About Everything: An Irreverent History of Philosophy. Stewart goes as far as trying to debunk almost the entire field of philosophy, partly for the specious use of obscure prose in many of the works of the greatest thinkers. Just for the record, of the Western philosophical canon I only like Augustine’s Confessions and Nietzsche’s Ecce homo in spite of the fact that both autobiographers became mad; Voltaire’s Candide, Schopenhauer’s Essays and Aphorisms and John Stuart Mill’s On Liberty, which I still like because free speech has now been curtailed in Mill’s native country. All of these works were written in clear prose. The Truth About Everything corroborated what I already knew but was afraid to say aloud. I would like to explain this book’s thesis not by quoting Stewart but by pointing out to something that I have figured out by myself.

The accepted view about Kant’s metaphysics is that it’s too complex and profound for the layman to understand. Those who study the snares of language, on the other hand, point out that Confucius detected the trick of using obscure language to pose as a profound metaphysician. Unlike the Chinese, the West hasn’t learned to detect this trick, and even today white nationalist sites such as Counter-Currents have presented obfuscating authors as deep thinkers (Alex Dugin, only the most recent case). A single example will suffice: If the interpretation of the universities is right, that is to say, if philosophers are so profound that only a few can grasp their ideas, how do you explain that Kant, the philosopher who introduced such obscurantism into the modern West, has been interpreted in dramatically different ways by such giants as Schopenhauer and Heidegger?

The answer is obvious. The goal of gratuitously obscuring language is that, by the heaviest and densest imaginable screens of smoke thus lifted, the philosopher’s System becomes impregnable to criticism. For instance, after honest psychologists found fatal flaws in Sigmund Freud’s edifice, the orthodox Freudian Jacques Lacan reacted by translating all of Freud’s claims, written in clear German prose, to an opaque French that only the initiate could understand. But of course: we don’t need to spend precious time trying to decipher the Ecrits of the charlatan Lacan to refute Freud. Just go directly to Freud’s original texts!

Today Counter-Currents published an erudite Evola essay on Buddhism, where Evola tries to spare the founder of Buddhism from any criticism from the Right by claiming that his philosophy was not effeminate like today’s liberals, but virile. But Evola represents exactly what is wrong with complex philosophizing that moved me to put one of his books into the trash can. In his essay published at C-C he even claims that Zen stands for a return to the original Buddhism, something that is patently untrue (see below). If you ask exactly what is Evola leaving out I would say that Buddhism contained the seeds of race treason for the Aryans in India. In a recent comment at this blog, Stubbs said:

Our race has had some really bad ideas over the ages: Alexander the Great telling all his soldiers to miscegenate, the Roman Empire making “citizens” out of aliens, the Aryan prince who founded Buddhism abolishing the caste system, White rulers in Egypt and Persia letting their countries go dark, not to mention the simple infighting and disorganization that would make our race easy prey for Jews or Muslims [and Mongols I would add]. Frankly, the existence of Buddhism should scare the White Nationalists who can’t think of anything but Jews.

Stubbs is right, and to prove it I have no choice but to debunk one of the most venerated religious icons of the West after the 1960s started to replace Christianity with Oriental cults and New Age nonsense.

♣

In my twenties I read The Three Pillars of Zen and was greatly impressed by the enlightenment experience (“satori”) of a Japanese executive in that book of Philip Kapleau. Since there were no Zen schools in the city where I lived it’s no coincidence that the same month that I became interested in Zen I fell, instead, in the Eschatology cult. Infinite soul odysseys I had to cross through before I stopped seeking my salvation in mysticism, cults or the paranormal. In the remainder of this entry I’ll dwell with some of my conclusions about Buddhism after my long, dark night of the soul was finally over.

Pali is an ancient dialect of India, the equivalent for Buddhists of Latin for Roman Catholics. A text called Tripiṭaka, written in Pali, is the oldest about the life of Buddha.

“Tripiṭaka” means three baskets or divisions called the Pali Canon: Digha Nikaya (Dialogues of the Buddha), Majjhima Nikaya (Sayings of average length) and Samyutta Nikaya (Similar sayings). This “Bible” of Buddhism is formidable: a mountain of literature that secular laymen cannot address as easily as the Torah, the New Testament or the Koran. Fortunately, Wisdom Publications sells a splendid English edition with extensive introductions, summaries of the sutras attributed to Buddha, and hundreds of notes and appendices in three volumes which together consist of more than 4,000 pages. Unlike the extensive Talmud the Pali Canon is, as to abstract ideas, very dense. In addition to abstract teachings it contains interpretations and the Order’s rule attributed to Buddha. The recent translation to English is an invaluable collection for those interested in Buddhism who don’t know Pali. However, since I follow my golden rule the dense psycho-metaphysics in The Long Discourses of The Buddha: a translation of the Digha Nikaya by Maurice Walshe (1995), The Middle Length Discourses of The Buddha: a translation of the Majjhima Nikaya by Bhikkhu Nanamoli (1995), and The Connected Discourses of The Buddha: a translation of the Samyutta Nikaya by Bhikkhu Bodhi (2002) might find a place in my personal library, but I’ll never read them from cover to cover. Never.

Evola did not read them either, since this translation is so recent. But whether we like it or not we have to start from the Pali Canon, aided by modern commentators, to speculate about who might have been the historical Buddha, if he was a historical figure at all. For the moment I must rely on other scholars for what I venture to say below.

The Buddha of dogma

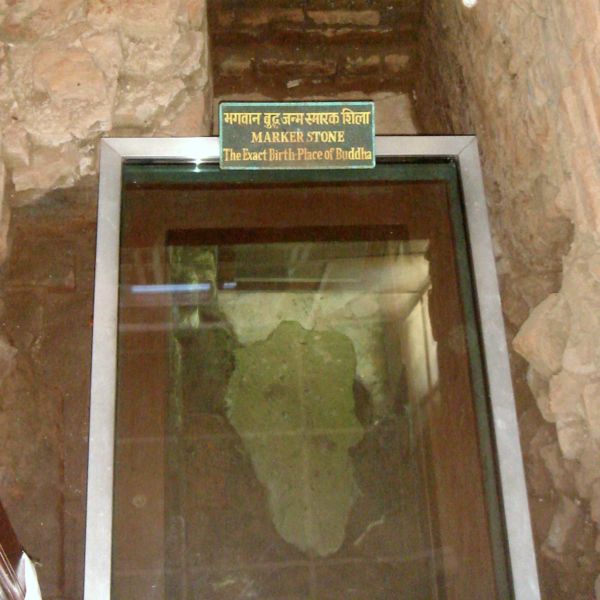

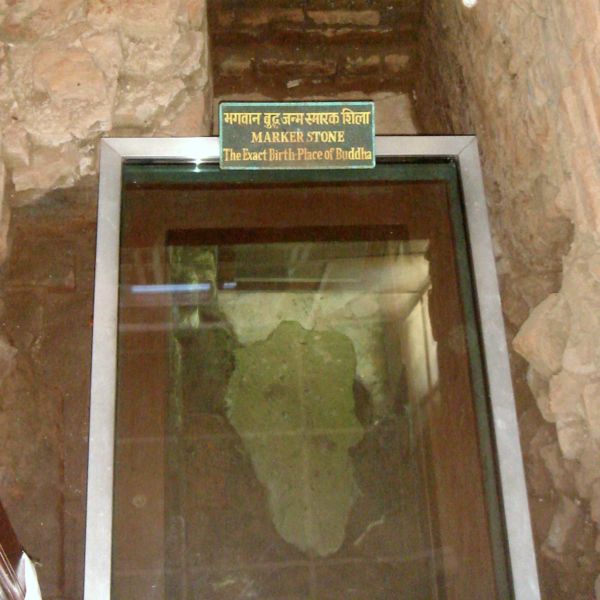

Buddha was born between the fifth and sixth centuries B.C. in a border of what is now Nepal and India (incidentally, a border crossed by one of my brothers in one of his searches for the “spiritual”). This seems to be true story. But legend says that Buddha was conceived when his virginal mother dreamed with a white elephant, which of course brings to mind the gospel’s nativity legends.

(Birthplace of Siddhatta in Lumbini)

Very few know that the narrative of the gospels of Matthew and Luke about the virginal conception of Jesus is not original. The Tripiṭaka also mentions a sage and a king worshiping the baby Buddha, which appears centuries after in the gospel narrative of the Magi. Moreover, the texts say that when Buddha was about thirty he suffered temptations by a devil (like Jesus in the desert at the same age) that wanted to prevent his enlightenment. And like the famous Sermon on the Mount of Jesus, Buddha is credited with the famous Sermon of Fire in which he speaks of the passions and human deceit (“Everything is on fire …”).

Like Jesus, Buddha is regarded by tradition as a man of extraordinary compassion for the downcast, and believers also attribute to him diverse miracles, like the Enlightened One having walked on the sea and calmed storms; stopped a plague in a village; more spectacular levitations than the ones attributed to Catholic saints, and even bilocations of his body. Like the Christian gospel, when Buddha died tradition says that the earth trembled and that the light of heaven was darkened. New Testament scholar Randel Helms suspects that the narrative of Jesus walking on the sea was modeled on Buddhist legends.

The Pali Canon claims that at thirty-five Buddha attained enlightenment; that the man reached the level of awakening from a world of illusion and thus became a “buddha” (legend speaks of previous Buddhas, like the Buddha Amida or the Buddha Kakusandha, but according to scholarship they are not historical figures). It is fascinating to compare the oldest and concise narrative of Buddha’s enlightenment with the legends about the same event, developed in much more recent types of Buddhism, like the Japanese Zen. But before doing it let’s think of the development of the Easter story in the New Testament.

The earliest New Testament writing, the epistles of Paul, do not talk of empty tombs, appearances of the risen Jesus, or the Ascension: they are only tortuous proclamations of faith without colorful resurrection narratives.

The Gospel of Mark, the earliest of the canonical gospels, speaks for the first time of the empty tomb but no Ascension or postmortem appearances of the risen Jesus to his disciples.

Matthew and Luke do talk about the apparitions, but Matthew omits Jesus’ Ascension into heaven.

Luke’s Acts mention the ascension but the theological type of Christology like “In the beginning was the Word…” was not yet developed.

Only in the last of the gospels to be written, the gospel of John, appears a developed Christology interwoven with other narratives about Jesus.

For the critical reader it is obvious that the writers of the New Testament added layer after layer of inspiring legends to a more primordial tale. And if the resurrection is the top event in Christianity, the Buddha’s enlightenment after his last meditation under the Bo tree is the maximum event for Buddhism. The story that conquered my imagination about the Buddha when I just left behind my teens was precisely the experience of the satori, or enlightenment, when he saw the planet Venus in the morning after his final session under the tree. “Wonder of wonders!” the Buddha said aloud. “Intrinsically all living beings are buddhas, endowed with wisdom and virtue, but because men’s minds have become inverted through delusive thinking they fail to perceive this.”

The mistake I made at twenty was taking for real the late and extremely elaborated narratives about the Buddha’s enlightenment: the story told by Yasutani-roshi in The Three Pillars of Zen. At that time I could not think as modern historians do: study the oldest texts if you want to speculate about what might have happened in history. However, had I read the new, most scholarly edition of the Tripiṭaka instead of The Three Pillars of Zen, no numinous spirit would have awakened in my mind, a spirit sparked by my reading the words of the roshi.

Once “enlightened,” the official story goes, Buddha’s mission was to teach the dharma to mankind and he delivered his first sermon. Rewording some later texts, the starting point of his teaching seems to be something like this: “Here is the sacred truth of suffering. Birth is suffering, aging is suffering… Here is the truth about the origin of suffering: desire.” And the way to suppress human suffering involves an austere life, a happy golden mean between the ruthless asceticism that the saint practiced and the worldly life. The eightfold path or “path to liberation” leads to nirvana.

The Siddhatta of history?

This eightfold path suggests that Buddha taught a kind of what Scientologists call “OT levels.” We could see the arhats or “perfected ones” as the “clears” or “liberated” in Ronald Hubbard’s psycho-babble cult. The Tripiṭaka also says that the five ascetics who had departed him then recognized the Buddha, underwent their “path to liberation” and reached the level of arhats. Buddha would be the leader of a sect with half hundred arhats or perfected men.

My comparison to modern, destructive cults may sound pretty irreverent, but that’s precisely what the irreverent history of Western philosophy by Matthew Stewart taught me. If we can mock the Wisdom of the West, why aren’t we allowed to mock the Wisdom of the East too?

White nationalist circles are fond of saying that Buddha was ethnically Aryan. But “The Buddha” is a title similar to “The Christ” of Christians to designate the man Jesus, or “The Prophet” of Muslims to refer to Mohammed. Unlike Jesus or Mohammed, the stories about Buddha were written several centuries after his death. If we want to speculate from such late legends, we must start with the name itself. As I never call “Christ” the human Jesus because I’m not Christian, from this line on I won’t call “Buddha” the human Siddhatta because I’m not Buddhist.

Sidhartha Gautama is Sanskrit for Siddhattha Gotama in Pali, the language that perhaps the founder of the religion spoke. If he existed he would have been called “Siddhatta” (Gotama was the name of his father). A person who has reached the “buddha” level simply means that he is an “enlightened one,” as the word Christ means “anointed one” in Greek (i.e., the messiah).

Like the charlatan Hubbard, who obscured his message with a mountain of unnecessary neologisms for terms already known in previous esoteric movements, Siddhatta was not original. Alara Kalama, his first teacher, had told Siddhatta that he, Siddhatta’s master, had reached “the sphere of nothing,” and his second teacher taught him to achieve “the sphere without perception and without no perception.” Whatever they told him in real life, these cryptic thoughts would inspire Siddhatta about his idea of the nirvana. Like Hubbard, all he did was to change the names and claim that “nirvana” was a plane superior to our own plane of existence.

After dropping his first teachers, and like the sanctimonious Christians of later centuries, it seems that Siddhatta practiced severe asceticism, increasingly eating less rice. Later artistic representations depict the anorexic Siddhatta with the skin of his stomach appearing almost next to his spine. The ancient text Majjhima Nikaya puts in Siddhatta’s mouth these words: “My buttocks seem wild ox hoof.” Siddhatta felt the danger of dying and accepted milk and rice offered by a peasant girl. He recovered gradually and his first disciples abandoned him after he quitted ascetics. Legend tells us that after surpassing the temptations of the devil, in his meditation sessions Siddhatta retrieved the memories of his past existences. (The founder of another religion, Hubbard, also claimed having remembered his past lives.)

Whether these stories were historical or not, may I remind my readers the most elementary rules of logic. Clearly, if reincarnation does not exist, both Hinduism and Buddhism are based on deception. Similarly, if Yahweh didn’t speak to Moses at Sinai, Judaism is based on a lie. If Jesus was not resurrected, Christianity is based on a lie. And if the angel did not speak to Muhammad, Islam is based on a lie. The only difference with the doctrine of reincarnation is that it was not original of Siddhatta: it preceded him within the metaphysical tradition of his homeland. But the postmodern psyche is shaped so that the mere fact that such an ancient doctrine enjoys wide acceptance makes it respectable.

Siddhatta visited the house of his father. Legend tells us that Yasodhara, the wife Siddhatta had abandoned, fell under his feet. Siddhatta’s father asked his son to establish the rule that no child could be ordered monk of the new religion, unless he obtained permission of his father. Siddhatta nodded. If the anecdote is historical it proves that the now “enlightened” man allowed himself to be treated like a child, again.

(Dhâmek Stûpa in Sârnâth, India, site of the first teaching of Siddhatta)

In Jetavana Siddhatta founded a famous monastery which became his headquarters and where he gave his sermons. The movement grew and soon many monasteries were founded in the major towns of the valley of Ganges. The Hindus believed that Siddhatta had a special trick for galvanic attraction. As Mother Teresa would later do also in India, Siddhatta visited the patients: a PR trick we see even in the careers of politicians during election campaigns.

Siddhatta died of old age, and it is instructive to know that before dying he became seriously ill. Similar to what the leader of the Church of Scientology, David Miscavige, said after his guru died in 1986—that Hubbard voluntarily got rid of his body—, Siddhatta’s followers believe that he passed away voluntarily. He was cremated; his relics divided to the satisfaction of the various groups.

♣

The central Buddhist doctrine, that suffering is caused by attachment to life, is a typical oriental escape from Life. After the magnificent sculptures in classical times of young Aryan bodies, the Eastern spirit of apathy and resignation (see my recent quote of Will Durant at Occidental Dissent) was reflected in Greek art through sculptures of sick old men. What a difference with the self-image of the Hellenes when Athens was at its height!

The other Siddhatta doctrine, that overcoming worldly attachment overcomes suffering, is the perfect corollary of such a pessimistic worldview. It is surprising that the religions that arose on dry soil, like Judaism and Christianity, have fantasized about a utopian future while moist religions, such as Buddhism and other Indian cults, preach the annihilation of the desire: one of the oldest definitions of nirvana. The central belief of Buddhism is that, if we get rid of attachment, we free ourselves from suffering. From this standpoint you will understand why devout Buddhists meditate hour after hour. The object is, to put it in contemporary terms, to turn the ego faculty off, an ego from which all suffering is derived.

Anyone who believes that we must cast out our desires would do well to shoot himself: the most direct way to destroy the ego, and forever. Siddhatta’s followers would object because of their sacred belief in the reincarnation chain, which condemns the suicidal individual to another, and probably worse, life. I remember how I was disappointed by the author of The Three Pillars of Zen while reading another of his books in a bookstore. The now “roshi-Kapleau” condemned both suicide and euthanasia. But the concept of nirvana is much like what we may experience after death: going nowhere, as we were before birth.

The painful way that the historical Siddhatta died contrasts with the serene depictions in Buddhist art. This is why in this post I did not reproduce any artistic iconography of India’s saint. They are all flawed and depict the Buddha of dogma, not the Siddhatta of history. More fundamental is the fact that the doctrine of reincarnation, as understood by Hinduists, Buddhists, Scientologists and many New Agers, is cowardly and un-Aryan.

Pace Evola I see no Übermensch in Siddhatta or in early Buddhism.