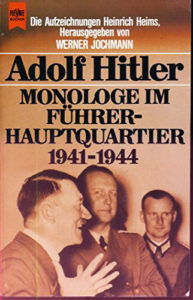

Führerhauptquartier [1]

Nacht vom 8. auf 9. 8. 1941 Nacht vom 9. auf 10. 8., 10. 8. 1941 mittags

10. 8. 1941 abends

Nacht vom 10. auf 11.8. 1941 H/Fu.

Die Geburtsstätte des englischen Selbstbewußtseins ist Indien. Vor 400 Jahren hatten die Engländer nichts davon. Die Riesenräume haben sie gezwungen, mit wenigen Menschen Millionen zu regieren. Mitbestimmend dabei war die Schwierigkeit der Versorgung größerer europäischer Einheiten mit Lebensmitteln und Gebrauchsgegenständen. Mit dieser Handvoll Leute das Leben der neuen Kontinente reglementieren zu wollen, konnte den Engländern nicht in den Sinn kommen; es hat auch keine anglikanische Missionstätigkeit gegeben. Das hatte das Gute, daß die fremden Kontinente ihre heiligen Güter nicht angetastet sahen.

Die Geburtsstätte des englischen Selbstbewußtseins ist Indien. Vor 400 Jahren hatten die Engländer nichts davon. Die Riesenräume haben sie gezwungen, mit wenigen Menschen Millionen zu regieren. Mitbestimmend dabei war die Schwierigkeit der Versorgung größerer europäischer Einheiten mit Lebensmitteln und Gebrauchsgegenständen. Mit dieser Handvoll Leute das Leben der neuen Kontinente reglementieren zu wollen, konnte den Engländern nicht in den Sinn kommen; es hat auch keine anglikanische Missionstätigkeit gegeben. Das hatte das Gute, daß die fremden Kontinente ihre heiligen Güter nicht angetastet sahen.

Der Deutsche hat sich überall in der Welt dadurch verhaßt gemacht, daß, wo er auftrat, er den Lehrer zu spielen anfing. Den Völkern war dadurch nicht der mindeste Dienst erwiesen, denn die ihnen vermittelten Werte waren für sie keine Werte. Der Pflichtbegriff in unserem Sinne existiert in Rußland nicht. Warum den Russen dazu erziehen wollen?

Der »Reichsbauer« soll in hervorragend schönen Siedlungen hausen. Die deutschen Stellen und Behörden sollen wunderbare Gebäulichkeiten haben, die Gouverneure Paläste. Um die Dienststellen herum baut sich an, was der Aufrechterhaltung des Lebens dient. Und um die Stadt ist auf 30-40 km ein Ring gelegt von schönen Dörfern, durch die besten Straßen verbunden. Was dann kommt, ist die andere Welt, in der wir die Russen leben lassen wollen, wie sie es wünschen; nur daß wir sie beherrschen. Im Falle einer Revolution brauchen wir dann nur ein paar Bomben zu werfen auf deren Städte, und die Sache ist erledigt. Einmal im Jahr wird dann ein Trupp Kirgisen durch die Reichshauptstadt geführt, um ihre Vorstellung mit der Gewalt und Größe ihrer steinernen Denkmale zu erfüllen.

Was für England Indien war, wird für uns der Ostraum sein. Wenn ich dem deutschen Volk nur eingeben könnte, was dieser Raum für die Zukunft bedeutet! Kolonien sind ein fraglicher Besitz; diese Erde ist uns sicher. Europa ist kein geographischer, sondern ein blutsmäßig bedingter Begriff. Man versteht jetzt, wie die Chinesen dazu gekommen sind, sich zum Schutz gegen die ewigen Einfälle der Mongolen mit einer Mauer zu umgeben, und man ist versucht, sich einen Riesenwall zu wünschen, der den neuen Osten gegen die mittelasiatischen Massen schirmt, aller Geschichte zum Trotz, die lehrt, daß im beschirmten Raum eine Erschlaffung der Kräfte eintritt! Am Ende ist die beste Mauer immer noch ein lebender Wall.

Wenn ein Land zu Evakuierungen ein Recht hat, so sind wir es, weil wir unsere eigenen Menschen wiederholt evakuiert haben: Aus Ostpreußen allein sind 800 000 Menschen ausgesiedelt worden. Wie empfindsam wir Deutschen sind, läßt sich daran erkennen, daß es uns ein Äußerstes an Brutalität zu sein schien, unser Land von den 600 000 Juden zu befreien, während wir die Evakuierung unserer eigenen Menschen widerspruchslos als etwas hingenommen haben, das sein muß. Wir dürfen von Europa keinen Germanen mehr nach Amerika gehen lassen. Die Norweger, Schweden, Dänen, Niederländer müssen wir alle in die Ostgebiete hereinleiten; das werden Glieder des Deutschen Reiches. Wir stehen vor der großen Zukunftsaufgabe, planmäßig Rassenpolitik zu treiben. Wir müssen das schon deshalb tun, um der Inzucht zu begegnen, die bei uns Platz greift. Die Schweizer werden wir allerdings nur als Gastwirte verwenden können.

Sümpfe wollen wir nicht bewältigen. Wir nehmen nur die bessere Erde und zunächst die allerbesten Gründe. Im Sumpfgebiet können wir einen riesigen Truppenübungsplatz anlegen von 350 auf 400 km, mit Strömen drin und allem Hindernis, das die Natur der Truppe bieten kann.

Es ist keine Frage, daß es für unsere kampfgeübten Divisionen ein Kleines wäre, heute über ein englisches Landheer Herr zu werden. England ist schon deshalb unterlegen, weil es im eigenen Land gar keine Ubungsmöglichkeiten hat; da müßten zuviel Schlösser verschwinden, wollten sie sich entsprechend große Räume erschließen.

Es hat in der Weltgeschichte bislang nur drei Vernichtungsschlachten gegeben: Cannae, Sedan und Tannenberg. Wir können stolz darauf sein, daß zwei davon von deutschen Heeren erfochten wurden. Dazu kommen jetzt unsere Schlachten in Polen, im Westen und heute im Osten. Alles andere sind Verfolgungsschlachten, auch Waterloo. Von der Schlacht im Teutoburger Wald machen wir uns falsche Vorstellungen; schuld daran ist die Romantik unserer Geschichtsprofessoren. Im Wald konnte man damals so wenig wie heute Kämpfe führen.

Was den russischen Feldzug angeht, standen sich zwei Vorstellungen gegenüber. Die eine: Stalin werde die Rückzugstaktik von 1812 wählen; die andere: wir würden mit erbittertem Widerstand zu rechnen haben; mit dieser stand ich ziemlich vereinsamt. Ich sagte mir, daß ein Aufgeben der Industriezentren Petersburg [Leningrad] und Charkow einer Selbstaufgabe gleichkommt, daß Rückzug unter diesen Umständen soviel wie Vernichtung ist und daß der Russe deshalb auf jeden Fall versuchen werde, diese Positionen zu halten. So ist dann auch der Einsatz unserer Kräfte erfolgt, und die Entwicklung hat mir recht gegeben.

Amerika würde, und wenn es vier Jahre wie wahnsinnig arbeiten wollte, das nicht zu ersetzen vermögen, was die russische Armee bis jetzt verloren hat. Wenn Amerika England Hilfestellung leistet, so geschieht das immer nur in der Erwägung, dem Augenblick näher zu kommen, wo man England zu beerben in der Lage ist.

Ich werde es nicht mehr erleben, aber ich freue mich für das deutsche Volk, daß es eines Tages mit ansehen wird, wie England und Deutschland vereint gegen Amerika antreten. Deutschland und England werden wissen, was eins vom anderen zu erwarten hat, und wir haben dann den rechten Bundesgenossen gefunden: Sie sind von beispielloser Frechheit, aber ich bewundere sie doch. Da haben wir noch viel zu lernen.

Wenn einer den Sieg unserer Waffen im Gebet erfleht, so ist es der Schah von Persien. Sobald wir bei ihm unten sind, hat er von England nichts mehr zu befürchten.[2]

Das erste wird sein, daß wir mit der Türkei einen Freundschaftsbund auf der Basis schließen, daß ihr der Schutz der Dardanellen überlassen ist. Keine Macht soll dort etwas zu suchen haben.

Was die Planmäßigkeit der Wirtschaft angeht, stehen wir noch ganz in den Anfängen und ich stelle mir vor, es ist etwas wunderbar Schönes, eine gesamtdeutsche und europäische Wirtschaftsordnung aufzubauen. Was würde beispielsweise allein damit gewonnen sein, daß es uns gelingt, die Wasserdämpfe, wie sie heute bei der Gasgewinnung entstehen, aber für die Wärmewirtschaft verlorengehen, zur Beheizung von Gewächshäusern zu verwenden, die unsere Städte den ganzen Winter über mit Frischgemüse und Früchten versehen müßten. Es gibt nichts Schöneres als Gartenwirtschaft. Ich habe bisher geglaubt, eine Wehrmacht könnte ohne Fleisch nicht auskommen; jetzt erfahre ich, daß die Heere der Antike sich nur in Zeiten der Ernährungsnot gezwungen gesehen haben, zum Fleisch zu greifen, daß sich die Heeresverpflegung der Römer fast ganz auf Getreide aufgebaut hat.

Nimmt man zusammen, was im europäischen Raum – Deutschland, England, nordische Länder, Frankreich, Italien – an Kräften zu schöpferischer Gestaltung schlummert, was sind daneben die amerikanischen Möglichkeiten?

England weist stolz auf die Bereitschaft der Dominions, zum Empire zu stehen. Gewiß, eine solche Bereitschaft ist etwas Schönes, aber: sie besteht nur so lange, als eine starke Zentralgewalt in der Lage ist, sie zu erzwingen.

Gewaltig wird sich auswirken, daß es über das ganze neue Reich weg nur eine Wehrmacht, eine SS, eine Verwaltung gibt!

Wie die in den Ring ihrer Mauern gezwungene Altstadt andere Baulinien hat als die moderne Stadtrandsiedlung, so werden wir die neuen Räume auf andere Weise als das Altreich regieren. Entscheidend ist nur, daß einheitlich geschieht, was geschehen soll.

Für den Bereich der Ostmark war es das Richtige, den Zentralstaat auf Kosten von Wien zu zerschlagen und die Kronländer wiederherzustellen. Mit einem Schlage ist damit eine Unzahl von Reibungsflächen verschwunden: Jeder der Gaue ist glücklich, sein eigener Herr zu sein.

Die Waffen der Zukunft? In erster Linie das Landheer, dann die Luftwaffe und erst an dritter Stelle die Seemacht! 400 Tanks im Sommer 1918, und wir würden den Weltkrieg gewonnen haben. Es war unser Unglück, daß die damalige Führung die Bedeutung der technischen Waffen nicht rechtzeitig erkannt hat.

Die Luftwaffe ist die jüngste Waffe, aber sie hat im Laufe weniger Jahrzehnte die größten Fortschritte gemacht, und noch kann nicht gesagt werden, daß sie auf dem Höhepunkt ihrer Möglichkeiten angelangt ist.

Die Marine dagegen hat seit dem Weltkrieg so gut wie keine Veränderung erfahren. Es ist etwas Tragisches, daß der Schlachtkreuzer, ein Inbegriff menschlicher Leistung in der Bewältigung des Materials, angesichts der Entwicklung der Luftwaffe zur Bedeutungslosigkeit herabgesunken ist. Er ist vergleichbar mit dem technischen Wunder, welches am Ende des Mittelalters ein mit seinem Pferd in prächtiger Rüstung geharnischter Ritter dargestellt hat.

Dabei entsprechen im Herstellungs-Aufwand einem Schlachtschiff tausend Bomber, und wieviel Zeit erfordert der Bau eines Schlachtschiffes! Sobald der geräuschlose Torpedo erfunden ist, bedeuten hundert Flugzeuge den Tod des Kreuzers. Und heute schon wird sich im Hafen kein großes Schlachtschiff mehr aufhalten können.

____________

[1] Dieses Gespräch ist von Picker fälschlich auf den 8.-10. September 1941 datiert worden.

[2] Im August 1941 wurde Persien von britischen und sowjetischen Truppen besetzt, um den Transport von Waffen und Versorgungsgütern für die Sowjetunion durch den Persischen Golf zu sichern. Schah Reza Chan Pahlewi dankte am 16. 9. 1941 zugunsten seines Sohnes Mohammed Reza Pahlewi ab.