Editor’s Note: We will now read excerpts from ‘Who was Hitler’s Lord?’, the eighth chapter of Hitler’s Religion by Richard Weikart:

______ 卐 ______

One of the most famous quotations from Hitler’s Mein Kampf is, “Hence today I believe that I am acting in accordance with the will of the Almighty Creator: by defending myself against the Jew, I am fighting for the work of the Lord.” Some construe this to mean Hitler believed in the Christian God and saw his war fighting against Jews as part of a religious battle that had been waged for centuries. Even though Hitler did not overtly appeal to Christianity in this statement, his use of the terms “Almighty Creator” and “Lord” would have been understood by many of his contemporaries (and those who currently ignore Hitler’s many anti-Christian utterances) as the Christian God. Anti-Semites in the Catholic or Protestant churches would have applauded him for doing “the work of the Lord.”

Nonetheless, there are major problems with suggesting that this statement indicates Hitler’s Lord was the Christian God. The aim of Hitler’s anti-Semitism—the “Lord’s work” he thought he was doing—was radically different from the goal of traditional Christian anti-Semitism (as mentioned in chapter six). The context itself suggests Hitler had some other kind of God in mind. Hitler was fulminating against the “Jewish doctrine of Marxism,” which he thought “rejects the aristocratic principle of Nature.” In the sentence immediately preceding his famous quotation about doing the work of the Lord, Hitler stated, “Eternal Nature inexorably avenges the infringement of her commands.” Four important points emerge from this. First, Hitler personified nature in this passage, ascribing to it characteristics that would normally be associated with God. Second, Hitler called nature eternal. If he thought nature existed forever, as this statement indicated, then the God he believed in could not have created nature sometime in the past. Thus Hitler’s God was not even a deistic, much less a theistic, God. The “Almighty Creator” he mentioned in the following sentence could not have created nature, making it highly probable that Hitler’s “Creator” was nature. Third, Hitler believed that nature’s commands defined morality, since he claimed nature issues commands…

Thus, the “Lord” on whose behalf Hitler was fighting the Jews was none other than nature deified. Samuel Koehne seems to agree with this interpretation, stating in a recent article, “At times he [Hitler] conflated this ‘divine will’ and ‘Nature,’ or the ‘commands’ of ‘Eternal Nature’ and the ‘will of the Almighty Creator.’” When Hitler called nature eternal in Mein Kampf, this was not just a slip of the pen (or typewriter). He referred to nature as eternal on several occasions throughout his career…

I am not, of course, the first person to conclude Hitler was a pantheist. In 1935, a religious commentator George Shuster placed the dominant German religious beliefs in the 1930s into five categories: Catholicism, Lutheranism, Judaism, neo-pantheism, and negativity toward religion. Though Hitler was influenced by the first two, his deepest cravings evinced pantheism, according to Shuster. Pius XI did not specifically mention Hitler in his encyclical Mit brennender Sorge, but he did combat therein the “pantheistic confusion” he saw in Nazi ideology. Shortly after World War II, the German theologian Walter Künneth interpreted Hitler’s religion as a form of apostasy from Christianity. He argued that when Hitler used terms like God, Almighty, and Creator, as he was wont to do, he redefined these terms in a pantheistic direction. Künneth stated, “In proper translation Hitler meant by ‘Creator’ the ‘eternal nature,’ by ‘Almighty’ and ‘Providence’ he meant the lawfulness of life, and by the ‘will of the Lord’ he meant the duty of people to submit themselves to the demands of the race.”

Robert Pois argues not only that Nazism advocated a religion of nature, but that it was central to the Nazi project. Their “religion was one which could and did serve to rationalize mass-murder,” he asserts. He only spends a few pages discussing Hitler’s own religious views, but he does portray Hitler as a pantheist who exalted “pitiless natural laws” above humanity. “What Hitler had done,” according to Pois, “was to wed a putatively scientific view of the universe to a form of pantheistic mysticism presumably congruent with adherence to ‘natural laws.’” In Pois’s view, Hitler’s pantheistic perspective was part of the Nazi revolt against the Christian faith and its values. Hitler “had virtually deified nature and he most assuredly identified God (or Providence) with it.” Pois might overstate the role played by the “religion of nature” in the Nazi Party, but he does demonstrate that it was not uncommon. André Mineau argues that the SS was inclined toward pantheism, stating, “The SS view of religion was a form of naturalistic pantheism that had integrated the biological paradigm.”

A number of other scholars who have analyzed Hitler’s religion concur it was pantheistic… Thomas Schirrmacher, in the most extensive and thorough analysis of Hitler’s religion to date, emphasizes the anti-Christian character of Hitler’s theology. However, Schirrmacher interprets Hitler as a non-Christian monotheist, specifically rejecting the idea that Hitler was a pantheist or deist. Oddly, however, Schirrmacher admits Hitler used the terms God, Almighty, and Creator synonymously with the rule of nature and the laws of nature.

Before I explain Hitler’s pantheistic religion in greater depth, it is important to understand that pantheism was an influential religious perspective in German-speaking lands (and elsewhere in Europe) before and during Hitler’s time. By the early twentieth century, two forms of pantheism had emerged, which I will call mystical pantheism and scientific pantheism. Mystical pantheists believed that the cosmos had a mind or will that was supreme, while scientific pantheists stressed determinism, i.e., the strict rule of natural laws. According to scientific pantheism, the laws of nature are an expression of the will of God and thus inescapable and ironclad. Mystical pantheism disagreed with this view, denying that science could fathom the mind of the universe. Mystical pantheism sometimes had affinities or even overlapped with animism, polytheistic nature-gods, or occultism. Scientific pantheism, on the other hand, shared similarities with atheism…

______ 卐 ______

Editor’s note

This is central to understanding what I call the religion of holy words, and only those philosophers who have speculated in astrophysical mysteries, as Roger Penrose has done, would understand anything. I mean how the beauty of the alphabet with which God created the universe (mathematics), to quote Galileo, is related to the beauty of Nature and the Aryan race in particular.

To defend Aryan beauty is to defend the emerging God that is being born with the pure, unpolluted Aryans, as can also be seen in this new series of images on European beauty that I have started in the new incarnation of this site. He who doesn’t feel beauty to the extent of wanting to preserve it, has not been initiated into the mysteries of our religion.

Weikart continues:

______ 卐 ______

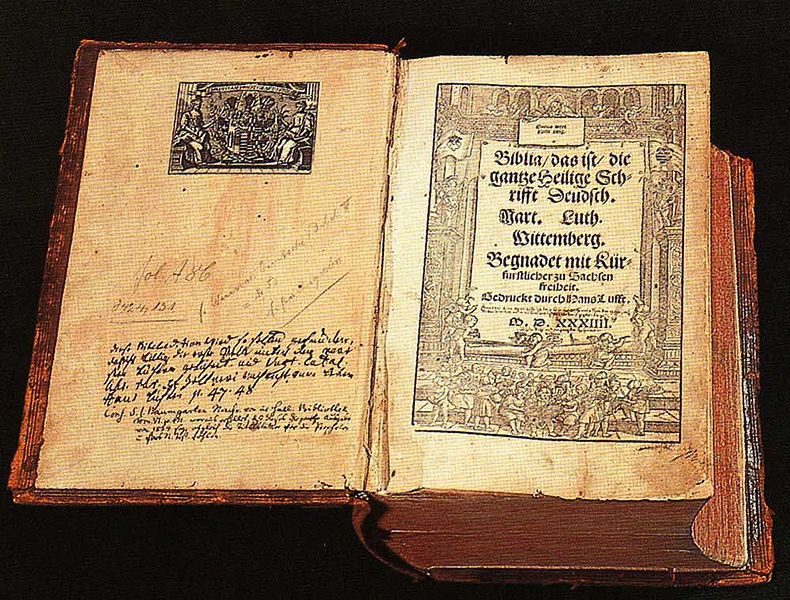

Some forms of anti-Semitism in the late nineteenth century favored pantheism as an antidote to the supposedly Jewish features of monotheism. For instance, Eduard von Hartmann, who is sometimes regarded as a forerunner of Freud because of his philosophizing about the unconscious, promoted pantheism as a replacement for Christianity in 1874. He believed Christianity was in its death throes. Hartmann was a popularizer of Schopenhauer’s philosophy, though he blended it with Schelling’s pantheism. Hartmann praised pantheism as the original religion of the Aryans, while denigrating monotheism as an inferior Semitic religion…

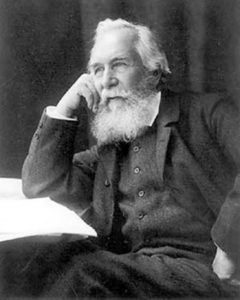

(The NS regime honored the German Darwinian biologist and pantheist Ernst Haeckel by including his portrait in the 1936 “Exhibition of Great Germans” in Berlin.)

(The NS regime honored the German Darwinian biologist and pantheist Ernst Haeckel by including his portrait in the 1936 “Exhibition of Great Germans” in Berlin.)

Another early twentieth-century figure who shared many affinities with Hitler’s religious views was Hans F. K. Günther, whom Hitler admired for his writings on Nordic racism. Hitler was so enthusiastic about Günther’s work that he pressed Wilhelm Frick to appoint him to a professorship in social anthropology at the University of Jena in 1930, and Hitler attended his inaugural lecture. When Hitler instituted a Nazi Party Prize for Art and Science at the 1935 Nuremberg Party Rally, he bestowed the first prize for science on Günther. In 1934, Günther discussed Nordic religion in his book Piety of a Nordic Kind. (The copy of this book that I examined was owned by the Adolf Hitler School, an elite Nazi educational institution, so, clearly the Nazis approved of this work.) In this book, Günther examined the religiosity of the Indo-Germanic people, not the specific content of their religions, yet he admitted that pantheism or some kind of mysticism is more compatible with Nordic religious inclinations than theism is. Like Hitler, he believed that the world is eternal, and he dismissed as an “Eastern” invention the idea that God created the world (“Eastern” likely meant Jewish in this context—it clearly was not referring to South or East Asian religions.) He also denied body-soul dualism, the need for redemption, and the existence of an afterlife, claiming instead that true religion should focus on this world…

Martin Bormann’s outspoken pantheistic views also seem similar to Hitler’s religion, and though he probably did not influence Hitler, he was able to disseminate his views to other Nazi Party leaders. In June 1941, Bormann, the head of the Nazi Party apparatus and one of the most powerful figures in the final four years of the Third Reich, issued a statement on the relationship between National Socialism and Christianity to all the Gauleiter. He told them that Nazis do not understand God as a human-like being sitting somewhere in the cosmos, but rather as the vastness of the universe itself. He continued,

“The force which moves all these bodies in the universe, in accordance with natural law, is what we call the Almighty or God. The assertion that this world-force can worry about the fate of every individual, every bacillus on earth, and that it can be influenced by so-called prayer or other astonishing things, is based either on a suitable dose of naiveté or on outright commercial effrontery.”

Bormann then equated morality with the laws of nature, which are the will of God. Though Rosenberg was critical of Bormann’s style, even he noted the content of Bormann’s missive was similar to Hitler’s ruminations during his Table Talks.

Bormann also equated God with nature in his private correspondence. In February 1940, he wrote to Rosenberg and encouraged him to help develop a handbook of moral instruction for the youth, so they could replace religion classes with moral education. One of the moral laws that Bormann wanted included was “love for the all-ensouled nature, in which God manifests himself even in animals and plants”…

When we examine Hitler’s religious statements in depth, we find that he often expressed views of nature and God that seem closer to pantheism than to any other religious position. Also, his friends and associates noticed that he had an extremely intense love of nature. His boyhood friend August Kubizek noted that Hitler loved nature “in a very personal way. He viewed nature as a whole. He called it the ‘Outside.’ This word from his mouth sounded so familiar, as though he had called it ‘Home’”…

Wagener also recalled Hitler discussing the celebration of Christmas. After noting that Christmas had originated as a pagan ceremony at the time of the winter solstice, Hitler indicated his approval for celebrating Christmas, but not in honor of Jesus’s birth. He asked, “Now, why shouldn’t our young people be led back to nature?” He hoped that Christmas festivities could lead children away from the church and “into the great outdoors, to show them the powerful workings of divine creation and make vivid to them the eternal rotation of the earth and the world and life.” He desired the Hitler Youth to introduce Christmas traditions in which “the young people should be led back to nature, they should recognize nature as the giver of life and energy. It is only in the freedom of nature that a human being can also open himself to a higher morality and a higher ethic.” Thus, Christmas Hitler-style would draw young people away from the church while fostering veneration for nature as the highest entity…

In a monologue in February 1942, Hitler discussed his plans for the observatory and planetarium he wanted to erect near his former hometown of Linz, Austria, which he intended to turn into a cultural capital of his Third Reich. Perched on a hill above Linz, the planetarium would replace the Catholic baroque pilgrimage church currently located there.

The church —this “temple of idols,” Hitler called it—would be torn down to make way for the observatory, which would become a Nazi pilgrimage site. The slogan on the observatory would read, “The heavens proclaim the glory of the Eternal One.” Hitler dreamed of tens of thousands of visitors flowing through this planetarium every Sunday, so they could comprehend the immense vastness of the universe. Thus Sunday would be a time to venerate nature, not the Christian God. Hitler hoped this contemplation of nature would instill in Germans a kind of religiosity that would replace the “superstition” of the churches.

He wanted people to be religious, but in an anticlerical (pfaffenfeindlichen) fashion. “We can do nothing better,” he said, “than to direct ever more people to these wonders of nature.” At the observatory, Hitler thought, people could learn, “A person can comprehend this and that, but he cannot dominate nature; he must know that he is a being dependent on the creation.” Hitler envisioned this observatory and planetarium as the new temples for the worship of nature. He was so serious about building the observatory that he had one of his favorite architects, Professor Gieseler, begin drawing up plans for it in 1942.

Another way that Hitler endowed nature with the attributes usually associated with God was by portraying it as the source of morality. In Mein Kampf, Hitler argued humans can never master nature but have to submit to its laws. An individual

“… must understand the fundamental necessity of Nature’s rule, and realize how much his existence is subjected to these laws of eternal fight and upward struggle. Then he will feel that in a universe where planets revolve around suns, and moons turn about planets, where force alone forever masters weakness, compelling it to be an obedient slave or else crushing it, there can be no special laws for man. For him, too, the eternal principles of this ultimate wisdom hold sway. He can try to comprehend them; but escape them, never.”

Nature dictates moral and social laws to humans, just as it controls the physical laws of the universe. Hitler reiterated this theme of nature being the source of morality several times in Mein Kampf, including passages discussed earlier in this chapter…

According to Hitler’s secretary Christa Schroeder, Hitler often discussed religion and the churches with the secretaries. She testified, “He had no kind of tie to the church. He considered the Christian religion an outdated, hypocritical and human-ensnaring institution. His religion was the laws of nature.” Schroeder confirmed what seems obvious from reading through Hitler’s monologues: he rejected Christianity and worshipped nature…

Hitler had little or no reason to pose as a pantheist, because this would not have appealed to a very large constituency. However, he had very strong political reasons to pose as a believer in a more traditional kind of God. Savvy politician that he was, he wanted to appeal to Germans of all religious persuasions, so he used more traditional God-language to win popular support. This is consistent with his own statements about the relationship between religion and propaganda, and it squares with what we know about his hypocritical use of Christian themes.

Another strong possibility is that Hitler’s view of God was not pantheistic, but panentheistic. Friedrich Tomberg argues this, claiming that Hitler embraced a panentheism that believed “everything is in nature, but nature is in God.” This would allow Hitler to equate nature with God, because panentheists see nature as divine. However, they also see God as having an existence beyond nature, too. A panentheist could construe God as intervening in history in some ways, though usually not in miraculous events. This could correspond roughly with the way Hitler described God blessing or favoring the German Volk.