Excerpted from the 15th and 16th articles of William Pierce’s “Who We Are: a Series of Articles on the History of the White Race”:

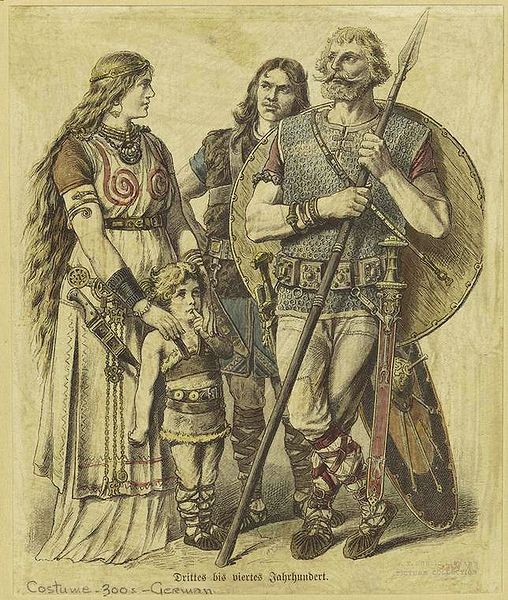

The philosopher Lucius Annaeus Seneca, also writing in the first century, shared Tacitus’ respect for the Germans’ martial qualities: “Who are braver than the Germans? Who more impetuous in the charge? Who fonder of arms, in the use of which they are born and nourished, which are their only care?”

Caesar, Tacitus, and other writers also described other attributes of the Germans and various aspects of their lives: their shrines, like those of the Celts and the Balts, were in sacred groves, open to the sky; their family life (in Roman eyes) was remarkably virtuous, although the German predilection for strong drink and games of chance must have been sorely trying to wives; they were extraordinarily hospitable to strangers and fiercely resentful of any infringements on their own rights and freedoms; each man jealously guarded his honor, and a liar was held in worse repute than a murderer; usury and prostitution were unknown among them.

[Here Pierce recounts the clash between the Germanics and the Romans under Caesar, Augustus and Tiberius. Then he adds:]

Five Decisive Things

During the 401 years between Hermann’s victory in the Teutoburger Forest and the sacking of the city of Rome by a German army in August 410, a great many things of historical importance occurred. We will be able to look at only a few of them in detail, however; we do not want to be distracted from our history of the race by the minutiae of political history, no matter how important.

Five things which happened or were ongoing during this period stand out as decisive, from a racial viewpoint. First, there was the continued decadence of the Romans, a matter we have already treated. Second, there was the growing Germanization of the Roman army. Third, there was the migration of the Goths from their home in Scandinavia back to the ancient Indo-European homeland in southern Russia. Fourth, there was the invasion of Europe by a non-White horde from the Far East: the Huns. And fifth, there was the final undermining of Roman strength by the spread of a new religion from the Levant—an Oriental religion of pacifism and egalitarianism which also began to have an effect on the Germans.

When Marcus Aurelius, the last Roman emperor able to inspire any real fear or respect in the Germans, tried to recruit troops to defend Rome’s Danubian border in 168, not even the threat of death induced Italians to enlist in the legions. The emperor finally resorted to conscripting all of Rome’s gladiators, most of whom were Celtic or German prisoners of war, into the army, whereupon the Roman masses, as addicted to their spectator sports as America’s masses are to their TV, threatened insurrection. “He deprives us of our amusements,” the populace cried out in anger against the emperor, “in order to make us philosophers like himself.” As they had become less martial, the Romans—or, rather, the Jews, Syrians, Egyptians and debased Greeks of the Empire who unworthily bore that once-honorable name—had grown ever more fond of the cruel blood sports of the Colosseum.

When Marcus Aurelius, the last Roman emperor able to inspire any real fear or respect in the Germans, tried to recruit troops to defend Rome’s Danubian border in 168, not even the threat of death induced Italians to enlist in the legions. The emperor finally resorted to conscripting all of Rome’s gladiators, most of whom were Celtic or German prisoners of war, into the army, whereupon the Roman masses, as addicted to their spectator sports as America’s masses are to their TV, threatened insurrection. “He deprives us of our amusements,” the populace cried out in anger against the emperor, “in order to make us philosophers like himself.” As they had become less martial, the Romans—or, rather, the Jews, Syrians, Egyptians and debased Greeks of the Empire who unworthily bore that once-honorable name—had grown ever more fond of the cruel blood sports of the Colosseum.

All-Volunteer Army

Until the end of the third century law prohibited the enlistment of foreigners in the Roman army. Although the law was often violated, it resulted in most of Rome’s soldiers being recruited from among the Celts and Germans of the conquered provinces during a period of about 150 years. By the time of Constantine not even the provinces could provide enough soldiers to defend the degenerate Roman Empire, and the greatest source of military manpower became the free Germans, who enlisted for purely mercenary motives.

By the middle of the fourth century, the Roman army was Roman in name only. Germans not only filled the ranks, but most of the officers, up to the highest levels of command, were Germans as well. Thus, the more or less continual state of war which existed between the free Germans and the Roman Empire during the third, fourth, and fifth centuries—up until 476, when the last Roman emperor was deposed and banished and a German leader ruled Italy as king—was not fought between Germans and Romans, but between Germans on the one side and Germans on the other.

Gold for Blood

The Romans bought their protection instead of fighting for it. Gold paid for blood for more than 200 years, but in the end all their money and their civilized cleverness were not enough.

If the Germans could have added a stronger sense of racial solidarity to their other virtues, they could have put an end to the sewer that was Rome 200 or even 300 years sooner than they did. They would not only have avoided spilling torrents of their own blood, but they could have stamped out a source of poison that, allowed to continue festering, ultimately would infect them.

Declining Rome’s many wars with the Germans involved a number of tribes. The incursions across the Danube into Pannonia that Marcus Aurelius bloodily repulsed in the second century were by tribes confederated with the Marcomanni, for example. During the third and fourth centuries the Franks raided across the Rhine into Gaul, and the Saxons harassed the coasts of that country and Britain. But it was the Goths above all the others who wrote the final chapters of the struggle between Germany and Rome.

Gothic Victory

After several skirmishes between Goths and Romans along the lower Danube, in the year 251 the Goths inflicted the worst defeat on the Romans they had suffered since the Hermannschlacht, annihilating a Roman army and killing its commander, the emperor Decius.

Within two more decades Rome had abandoned all claim to Dacia, and the province which Trajan had conquered 150 years earlier was thenceforth firmly in German hands, with the Danube once again the border between Rome and Germany.