This topic is related to my work in Spanish, which deals precisely with parents who devour the souls of their children.

Tag: History

Holocaust

Revisionist Scott Smith recently wrote the following in the vigorous discussion about the Holocaust now taking place on Counter-Currents:

I conceded a long time ago that [Raul] Hilberg’s 5.1 Jewish million mortality figure could be true.

Wow! I think it’s very healthy that the issue is being aired on Counter-Currents. I very rarely comment on that webzine, but this time I did so given the importance of breaking the taboo that exists in certain quarters of the racial right, and the only way to achieve consensus is to start talking to each other.

In my opinion, even if the official figure of six million Jews killed in the Holocaust is true (which I highly doubt), that shouldn’t weaken our faith. As a Swede commented quite a few years ago on the previous incarnation of this site:

What is certain is that the Holocaust would not have produced any debilitating psychological effect on non-Christian whites. (By Christianity I mean ‘Christian morality.’ Most atheists in the West are still Christian, even if they don’t believe in God or Jesus.) Being emotionally affected by the Holocaust presupposes that you think: (1) Victims and losers have intrinsically more moral value than conquerors and winners, (2) Killing is the most horrendous thing a human can do, (3) Killing children and women is even more horrendous and (4) Every human life has the same value.

None of these statements ring true to a man who has rejected Christian morality. Even if the Holocaust happened, I would not pity the victims or sympathise with them. If you told the Vikings that they needed to accept Jews on their lands or give them gold coins because six million of them were exterminated in an obscure war, they would have laughed at you.

This passage was included on page 83 of my anthology On Exterminationism. I believe that the commenters on Counter-Currents, whether Holocaust deniers or Holocaust affirmers, have not reached the level of the Swede because of their Christian programming.

Below,

pages 97-107 of the December 2024 edition of Benjamin’s The Less Than Jolly Heretic:

______ 卐 ______

I’ve become very anti-Christian over the recent years, seeing this slavish faith-based ideology as perhaps the primary cause of European civilisational collapse, having read quite closely into the likes of Catherine Nixey’s The Darkening Age, Revilo P. Oliver’s The Origins of Christianity, Tom Holland’s Dominion, and Charles Freeman’s The Closing of the Western Mind, and some abridged translations of Christianity’s Criminal History by Karlheinz Deschner, reinforced by the historical Roman writings of Celsus, Porphyry of Tyre, and the Emperor Julian, and, as with Edward Gibbon, have considered Christianity’s responsibility for the fall of Rome (and the theocratic brutality of Byzantium and the Dark Ages that effectively ended European science for well over a millennium, torturing and exterminating those Europeans who tried to hold out against the impositions of countless generations of bloodthirsty, ignorant, perverted Christian regimes, Europe split for seventeen centuries by terrible Christian sectarian warfare).

I have also considered its post-Enlightenment transition into liberalism and that all-encompassing secular ‘Neochristianity’, in the inspirational words of César Tort. This value system has conditioned a knee-jerk egalitarianism and relativistic weakness, a morality that Friedrich Nietzsche famously derided as fit only for slaves, a racially suicidal, life-hating framework of passivity, submission, and out-group preference, in complete contrast to the master morality values of Republican Rome and the cohesive Indo-European civilisations of the ancient world.

Drawing from a translated summary of Demolish Them by Vlassis Rassias, provided in original form on the West’s Darkest Hour blog, we can chart the principal Christian moves to destroy the Classical world. It’s worth noting that Christians referred to European advocates of Greco-Roman civilisation as ‘Gentiles,’ a Semitic term, before transitioning into even more erroneous and derogatory descriptors.

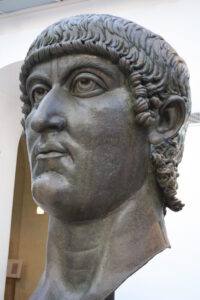

In 314, after the full legalisation of Christianity, the Christian church moved to attack the Gentiles. The Council of Ancyra denounced the worship of the Goddess Artemis. In 324, the Emperor Constantine declared Christianity as the only religion of the Roman Empire. At Dydima in Asia Minor, he sacked the Oracle of God Apollo and tortured its priests to death. He also evicted the Gentiles from Mt. Athos and destroyed all local Hellenic Temples. In 326, Constantine destroyed the Temple of God Asclepius in Aigeai in Celicia and many Temples of Goddess Aphrodite in Jerusalem, Aphaca, Mambre, Phoenice, and Baalbek. In 330, Constantine looted the treasures and statues of the Greco-Roman Temples of Greece to decorate his new capital of the empire, Nova Roma (the city of Constantinople), and in 335, went on to sack the Temples of Asia Minor and Palestine and ordered the execution by crucifixion of Gentile priests as “magicians and soothsayers” including the Neoplatonist philosopher Sopater of Apamea.

In 314, after the full legalisation of Christianity, the Christian church moved to attack the Gentiles. The Council of Ancyra denounced the worship of the Goddess Artemis. In 324, the Emperor Constantine declared Christianity as the only religion of the Roman Empire. At Dydima in Asia Minor, he sacked the Oracle of God Apollo and tortured its priests to death. He also evicted the Gentiles from Mt. Athos and destroyed all local Hellenic Temples. In 326, Constantine destroyed the Temple of God Asclepius in Aigeai in Celicia and many Temples of Goddess Aphrodite in Jerusalem, Aphaca, Mambre, Phoenice, and Baalbek. In 330, Constantine looted the treasures and statues of the Greco-Roman Temples of Greece to decorate his new capital of the empire, Nova Roma (the city of Constantinople), and in 335, went on to sack the Temples of Asia Minor and Palestine and ordered the execution by crucifixion of Gentile priests as “magicians and soothsayers” including the Neoplatonist philosopher Sopater of Apamea.

In 341, Emperor Constantius, the son of Constantine, persecuted “all the soothsayers and the Hellenists,” imprisoning and executing many Gentile Hellenes. In 346, there were large-scale persecutions against the Gentiles in Constantinople, during which the famous orator Libanius was banished as a “magician.” In 343, an edict of Constantius ordered the death penalty for all kinds of worship through “idols,” and a new edict in 354 ordered the closing of all Greco-Roman Temples, some of them to be turned into brothels or gambling rooms, and their priests were executed. In various cities of the empire, libraries began to be burnt, and lime factories were built next to the closed Temples. A large part of sacred Gentile architecture was turned to lime. A further edit in 356 ordered the Temples destroyed altogether and the execution of all “idolators,” and in 357, Constantius outlawed all methods of Divination.

In 341, Emperor Constantius, the son of Constantine, persecuted “all the soothsayers and the Hellenists,” imprisoning and executing many Gentile Hellenes. In 346, there were large-scale persecutions against the Gentiles in Constantinople, during which the famous orator Libanius was banished as a “magician.” In 343, an edict of Constantius ordered the death penalty for all kinds of worship through “idols,” and a new edict in 354 ordered the closing of all Greco-Roman Temples, some of them to be turned into brothels or gambling rooms, and their priests were executed. In various cities of the empire, libraries began to be burnt, and lime factories were built next to the closed Temples. A large part of sacred Gentile architecture was turned to lime. A further edit in 356 ordered the Temples destroyed altogether and the execution of all “idolators,” and in 357, Constantius outlawed all methods of Divination.

In 359, massive death camps were built in Skythopolis in Syria for the torture and execution of arrested Gentiles from all around the empire. In 361, a new, non-Christian Emperor, Julian, pronounced religious tolerance and called for the restoration of the various pre-Christian cults but was assassinated in 363. In 364, the Emperor Flavius Jovianus ordered the burning of the library of Antioch, an Imperial edict ordered the death penalty for all Gentiles who worshipped their ancestral Gods, and three separate further edicts ordered the confiscation of all properties of Temples and the death penalty for participation in Greco-Roman rituals, even in private. In 365, an Imperial edict forbade Gentile army officers to command Christian soldiers.

In 370, Emperor Valens ordered a tremendous persecution of Gentiles throughout the Eastern Empire. In Antioch, the ex-governor Fidustius, the priests Hilarius and Patricius, and many other non-Christian believers were executed. All friends of Julian, such as his personal physician Orebasius, the Greek medical writer, the Roman historian Sallustius, and Pegasius, the custodian of the Temple of Minerva, were persecuted, and the philosopher Simonides was burnt alive whilst the philosopher Maximus was decapitated. In 372, Emperor Valens ordered the governor of Asia Minor to exterminate the Hellenes and all documents of their wisdom.

In 370, Emperor Valens ordered a tremendous persecution of Gentiles throughout the Eastern Empire. In Antioch, the ex-governor Fidustius, the priests Hilarius and Patricius, and many other non-Christian believers were executed. All friends of Julian, such as his personal physician Orebasius, the Greek medical writer, the Roman historian Sallustius, and Pegasius, the custodian of the Temple of Minerva, were persecuted, and the philosopher Simonides was burnt alive whilst the philosopher Maximus was decapitated. In 372, Emperor Valens ordered the governor of Asia Minor to exterminate the Hellenes and all documents of their wisdom.

In 373, there was a new prohibition on Divination and the introduction by Christians of the slang term “Pagan” (from the Late Latin word pagani, meaning “peasants,” by extension as “rustic,” “unlearned,” “yokel,” or “bumpkin.”) The Greco-Roman polytheists did not refer to themselves as Pagans. The ‘Pagans,’ driven from their places of learning and religious practice and fearing for their lives, had become increasingly rural and provincial relative to the Christian population. Subsequently, Christians denigrated Paganism as “the religion of the peasantry.”

In 375, the Temple of God Asclepius in Epidaurus in Greece was closed. Again in 380, an edict of Emperor Flavius Theodosius decreed Christianity the exclusive religion of the Roman Empire, requiring that “all the various nations, which are subject to our clemency and moderation, should continue in the practice of that religion, which was delivered to the Romans by the divine Apostle Peter.” Non-Christians were referred to as “loathsome, heretics, stupid and blind,” and in another edict, he referred to all those who did not believe in the Christian god as “insane” and outlawed all disagreements with the Church dogmas. Ambrosius, the Bishop of Milan, began to destroy all the Temples in his area, and Christian priests led the mob against the Temple of Goddess Demeter in Eleusis and tried to lynch the hierophants Nestorius and Priskus. The 95-year-old Nestorius ended the Eleusinian Mysteries and announced a predominance of mental darkness over the race.

In 381, Emperor Theodosius removed all rights from any Christians who returned to the Greco-Roman religion. Throughout the Eastern Empire, more Temples and libraries were looted and burned down. Even simple visits to the Hellenic Temples were banned. In Constantinople, the Temple of Goddess Aphrodite was turned into a brothel, and the Temple of Sun and the Temple of Artemis were turned into stables.

In 381, Emperor Theodosius removed all rights from any Christians who returned to the Greco-Roman religion. Throughout the Eastern Empire, more Temples and libraries were looted and burned down. Even simple visits to the Hellenic Temples were banned. In Constantinople, the Temple of Goddess Aphrodite was turned into a brothel, and the Temple of Sun and the Temple of Artemis were turned into stables.

Then, in 384, Theodosius ordered the devout Christian Praetorian Prefect, Maternus Cynegius, to cooperate with the local bishops of Northern Greece and Asia Minor to destroy more Hellenic Temples. From 385 to 388, “Saint” Marcellus and his armed gangs scoured the countryside, sacking and destroying hundreds of Hellenic Temples, shrines, and altars, including the Temple of Edessa, the Cabeireion of Imbros, the Temple of Zeus in Apamea, the Temple of Apollo in Dydima, and all the Temples of Palmyra. Many thousands more Gentiles were rounded up and sent to the Skythopolis death camps to be executed.

In 386, Theodosius outlawed the care of sacked Temples, and in 388 outlawed public talks on religious subjects. In 389 and 390, all non-Christian calendar systems were outlawed, and hordes of emboldened desert hermit fanatics flooded into the Middle Eastern and Egyptian cities, destroying statues, altars, libraries, and Temples and lynching the Gentile inhabitants. Theophilus, the Patriarch of Alexandria, began a heavy persecution of Gentiles and turned the Temple of Dionysos into a church, burnt down the city’s Mithraic Temple and then destroyed the Temple of Zeus, and mocked the priests as ludicrous before the laughter of the Christian crowd, before stoning them to death as the mob profaned their sacred images.

In 391, a new edict of Theodosius prohibited visits to Temples and the crime of merely looking at vandalised statues. In Alexandria, Gentiles led by the philosopher Olympius revolted, and street fights broke out before they locked themselves inside the fortified Temple of the God Serapis. Following a violent siege, the Christians occupied the building, demolished it, burnt its famous library, and profaned the Greco-Roman cult images.

In 392, Theodosius outlawed all non-Christian rituals as “Gentile superstitions.” The Mysteries of Samothrace were ended, and their priests slaughtered. In Cyprus, “Saint” Epiphanius and “Saint” Tychon destroyed almost all the Temples of the island and exterminated thousands more Gentiles. The local Mysteries of Goddess Aphrodite were ended. An edict by Theodosius declared, “The ones that won’t obey Pater Epiphanius have no right to keep living on the island.”

In 393, the Pythian Games at Delphi, the Aktia of Nikopolis, and the Olympic Games were outlawed as “idolatry,” and Christians sacked the Temples of Olympia. In 395, two new edicts led to the persecution of Gentiles. The Emperor Flavius Arcadius directed hordes of baptised Goths led by Alaric and the Christian monks to sack and burn the Hellenic cities, including, among others, Dion, Delphi, Megara, Corinth, Pheneos, Argos, Nemea, Lycosoura, Sparta, Messene, Phigaleia and Olympia, and then slaughtered and enslaved the inhabitants, burning all Temples. They burnt down the Eleusinian Sanctuary and had all its priests burnt alive, including the hierophant Mithras Hilarius. In 396, Flavius Arcadius declared Paganism to be treated as high treason, and the few remaining priests and hierophants were imprisoned. Then, in 397, Flavius Arcadius ordered all Temples still erect to be demolished.

In 393, the Pythian Games at Delphi, the Aktia of Nikopolis, and the Olympic Games were outlawed as “idolatry,” and Christians sacked the Temples of Olympia. In 395, two new edicts led to the persecution of Gentiles. The Emperor Flavius Arcadius directed hordes of baptised Goths led by Alaric and the Christian monks to sack and burn the Hellenic cities, including, among others, Dion, Delphi, Megara, Corinth, Pheneos, Argos, Nemea, Lycosoura, Sparta, Messene, Phigaleia and Olympia, and then slaughtered and enslaved the inhabitants, burning all Temples. They burnt down the Eleusinian Sanctuary and had all its priests burnt alive, including the hierophant Mithras Hilarius. In 396, Flavius Arcadius declared Paganism to be treated as high treason, and the few remaining priests and hierophants were imprisoned. Then, in 397, Flavius Arcadius ordered all Temples still erect to be demolished.

In 398, the Fourth Church Council of Carthage prohibited the study of Gentile books by all citizens, their bishops included. Porphyrius, the bishop of Gaza, demolished almost all Temples in his city, leaving only nine to continue functioning. In 399, a new edict from Flavius Arcadius ordered the last of the Temples, almost exclusive now to the depths of the countryside, to be immediately demolished, and, in 400, bishop Nicetas destroyed the oracle of God Dionysus in Vesai and baptised all Gentiles living in the area. In 401, the Christian mob of Carthage lynched Gentiles and destroyed “idols.” In Gaza, the new “Saint” Porphyrius sent his followers to lynch Gentiles and destroyed the remaining nine Temples still active in the city. The Fifteenth Council of Chalcedon ordered all Christians who still retained good family relations with their Gentile relatives to be excommunicated (even after the death of these relatives).

In 405, John Chrysostom sent hordes of grey-clad monks armed with iron bars and clubs to destroy the “idols” in all the cities of Palestine and, in 406, collected funds from rich Christian women to financially support the demolishment of Hellenic Temples. The Temple of Goddess Artemis was destroyed in Ephesus, and in Salamis in Cyprus, “Saint” Epiphanius and “Saint” Eutychius continued the total destruction of Temples and sanctuaries and the persecution of Gentiles. A new edict in 407 once more outlawed all non-Christian acts of worship.

In 408, the Emperor Honorius of the Western Empire and the Emperor Flavius Arcadius of the Eastern Empire came together and ordered all Temple sculptures destroyed or confiscated. Private ownership of the statues was outlawed. The local bishops led new book-burning persecutions, and any judges showing pity for Gentiles were also persecuted. In Alexandria, a few days before the Judaeo-Christian festival of Pascha-Easter, bishop Cyrillis ordered the mob to attack and hack down the beautiful Neoplatonist philosopher Hypatia. The Christians paraded pieces of her body through the city and burnt them together with her books at a place called Cynaron. A fresh persecution started, and all Hellenic priests in North Africa were crucified or burnt alive.

In 408, the Emperor Honorius of the Western Empire and the Emperor Flavius Arcadius of the Eastern Empire came together and ordered all Temple sculptures destroyed or confiscated. Private ownership of the statues was outlawed. The local bishops led new book-burning persecutions, and any judges showing pity for Gentiles were also persecuted. In Alexandria, a few days before the Judaeo-Christian festival of Pascha-Easter, bishop Cyrillis ordered the mob to attack and hack down the beautiful Neoplatonist philosopher Hypatia. The Christians paraded pieces of her body through the city and burnt them together with her books at a place called Cynaron. A fresh persecution started, and all Hellenic priests in North Africa were crucified or burnt alive.

In 416, the inquisitor Hypatius, “The Sword of God,” exterminated the last Gentiles of Bithynia. In Constantinople, all non-Christian army officers, public employees, and judges were dismissed. In 423, Emperor Theodosius II declared that all Gentile religion was nothing more than “demon worship” and ordered those who persisted in practicing it to be imprisoned and then tortured. In 429, the Parthenon on the Acropolis of Athens, holding the Temple of Goddess Athena, was sacked.

Then, in 435, a new edict of Emperor Theodosius II ordered the death penalty for all “heretics.” Judaism was considered the only legal and non-heretical non-Christian religion. In 438, Theodosius II’s new edict incriminated Gentile “idolatry” as the reason for a recent plague. Between 440 and 450, the Christians succeeded in demolishing all Temples, altars, and monuments in Athens and Olympia, and Theodosius II ordered all non-Christian books burned, and all the Temples of the city of Aphrodisias (the city dedicated to Goddess Aphrodite) were demolished. All libraries were burnt down, and the city was renamed Stauroupolis, “City of the Cross.”

Then, in 435, a new edict of Emperor Theodosius II ordered the death penalty for all “heretics.” Judaism was considered the only legal and non-heretical non-Christian religion. In 438, Theodosius II’s new edict incriminated Gentile “idolatry” as the reason for a recent plague. Between 440 and 450, the Christians succeeded in demolishing all Temples, altars, and monuments in Athens and Olympia, and Theodosius II ordered all non-Christian books burned, and all the Temples of the city of Aphrodisias (the city dedicated to Goddess Aphrodite) were demolished. All libraries were burnt down, and the city was renamed Stauroupolis, “City of the Cross.”

Between 457 and 491, among others, the physician Jacobus and the philosopher Gessius of Petra were executed, whilst the Roman politician Severianus of Damascus, the Greek historian Zosimus, and the Greek mathematician and architect Isidorus of Miletus were tortured and imprisoned. The proselytiser Conon and his followers exterminated the last Gentiles on the island of Imbros in the North-East Aegean. The last worshippers of Lavranius Zeus were exterminated in Cyprus. The majority of the Gentiles of Asia Minor were exterminated, despite a desperate revolt against the Emperor and the Church between 482 and 488, and more Hellenic priests hiding ‘underground’ were arrested, publicly humiliated, and tortured, then executed.

By 515, baptisms had become obligatory, even among those who professed to already be Christian. The Emperor Anastasius of Constantinople ordered the massacre of Gentiles in the Arabian city of Zoara and the demolishing of the Temple of the local God Theandrites. In 528, Emperor Jutprada outlawed the alternative Olympian Games of Antioch and ordered the execution by fire, crucifixion, tearing to pieces by wild beasts, or cutting by iron nails of all who practiced “sorcery, divination, magic, or idolatry” and prohibited all teachings by “…the ones suffering from the blasphemous idolatry of the Hellenes”, then, in 529, he outlawed the Athenian Philosophical Academy and had all its property confiscated.

In 532, the fanatical inquisitor-monk Ioannis Asiacus led a crusade against the Gentiles of Asia Minor, put hundreds of Gentiles to death in Constantinople, and bloodily converted them to Christianity in Phrygia, Caria, and Lydia and in 556, inquisitor the Emperor Jutprada ordered Amantius to go to Antioch, to find, arrest, torture, and execute the last Gentiles and to burn all private libraries down. In 562, mass arrests, public humiliations, tortures, imprisonments, and executions were conducted in Athens, Antioch, Palmyra, and Constantinople. Within 35 years of Asiacus’ crusade, 99 churches and 12 monasteries had been built on the sites of demolished Temples.

Between 578 and 582, Christians tortured and crucified almost all the Gentiles around the Eastern Empire and exterminated the last Hellenes of Baalbek, now named Heliopolis. In Antioch, a secret Temple of Zeus was discovered and attacked, causing the priests to commit suicide. The captured Gentiles, including Vice Governor Anatolius, were tortured and sent to Constantinople to be fed to wild beasts and crucified when they were not devoured alive, their mutilated corpses dragged through the streets by Christians, and then thrown unburied in the city dump. Emperor Mauricius conducted further persecutions in 583, and in 590, Christian accusers ‘discovered Pagan conspiracies’ throughout the Eastern Empire, and a new wave of torture and executions erupted.

In 692, the Penthekte Council of Constantinople prohibited the last remains of Calends, Brumalia, Anthesteria, and other Hellenic Dionysian festivals. By 804, the last Gentiles living in Laconia in Greece had still resisted all attempts by Tarasius, the patriarch of Constantinople, to convert them, but they were, in the end, violently converted between 950 and 988 by the Armenian “Saint” Nikon.

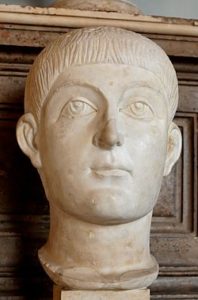

This piece from a statue of Emperor Hadrian, which must have measured around 5 meters, was found in present-day south-central Turkey, where Christianity took root early.

There are many more examples of this barbarity, but this provides a basic overview of why I hold my perspectives. The most important factor, beyond the beautiful architectural physicality of their Temples and statues being defiled and destroyed, and the amassed wisdom of their many libraries lost forever, is that the Europeans referred to as “Gentiles”, those massacred throughout this violent centuries-long campaign of anti-European terror—conducted by their fellow European citizens and their leaders from within the same civilisation under the same race of people—methodically severed the European citizens from their Aryan Gods and instead subjected them to a forced conversion to this god of a foreign enemy, and the holy teachings and writings originally compiled by that enemy.

The gospels were originally written by Jews after all, much as the entire Old Testament is a Jewish mythology, that Judaic archetype of Jesus subversively inverting the European values to the values of their racial enemy, and the additional values they designed ‘for export only’, so the newly radicalized cult of Europeans could further impose these alien values among their own race by obscene brutality and blind torments and misery, these traitorous egalitarian submission and pacifism values held now near-unanimously by Europeans in the 21st Century, and held subconsciously, unaware that, though they have—in the general public understanding—dropped that god for atheism, their unthinking moral axiology and puritanism is still entirely Christian (and it certainly is unthinking beyond any rationalizations they can attribute in aftermath), an ethical framework of far more profound significance than the standard assumption by atheist progressives that by Christian ethics we mean merely an organised opposition to pornography, abortion and homosexuality as displayed by American conservative evangelicals, and irrespective of a liberal humanist’s scepticism over the existence of the supernatural and of the divine aspects of Christian monotheism.

The arbitrary value shift has been subsumed, and now, when one talks of being ‘good,’ or ‘moral’—or specifically obsesses over the moral value of an act at all, as Friedrich Nietzsche reminded us in his Twilight of the Idols—we can take it as read that they are in alignment with the morals presented to us in the Ten Commandments, and by the incoherent single-source literary subversions of a radical millenarian cult-leader archetype, the inverse of an Eliot Goldstein creation, this revolutionary fiction—as if morality had no other value-system, and as if nothing worthy had come before, or had been a mere barbarity of its own!—with us only able to view the pre-Christian Greco-Roman civilisation’s societal codes and cultural drives through a 2000-year post-revolutionary Christian moral lens, in unthinking retroprojection—our definitive modern paradigm—the Greco-Roman world now appearing alien to us, or somehow cruel.

The arbitrary value shift has been subsumed, and now, when one talks of being ‘good,’ or ‘moral’—or specifically obsesses over the moral value of an act at all, as Friedrich Nietzsche reminded us in his Twilight of the Idols—we can take it as read that they are in alignment with the morals presented to us in the Ten Commandments, and by the incoherent single-source literary subversions of a radical millenarian cult-leader archetype, the inverse of an Eliot Goldstein creation, this revolutionary fiction—as if morality had no other value-system, and as if nothing worthy had come before, or had been a mere barbarity of its own!—with us only able to view the pre-Christian Greco-Roman civilisation’s societal codes and cultural drives through a 2000-year post-revolutionary Christian moral lens, in unthinking retroprojection—our definitive modern paradigm—the Greco-Roman world now appearing alien to us, or somehow cruel.

As with the writings of Richard Carrier, David Fitzgerald, and David Skrbina, I am convinced that the character of Jesus is mythological, a subversive creation of Paul—and otherwise missing from the historical record (one cannot trust Flavius Josephus as a single external to the Bible source due to the likelihood of forgery)—invented for the purposes of irreversibly undermining an already weakened Roman Empire and to impede the maintenance of its grasp on Judea, manipulating the fundamental attitudes of his hated enemy to the point that their society would fall apart in revolution from the ground up, the universal egalitarianism of the Judaic doctrine of Christianity moulding the slave-classes into furious zealots, violently intolerant of the ‘paganism’ of the Greco-Roman tradition and the accepting pluralism of Roman religious belief, and their centuries of rational philosophy, mathematics, and analytical science, with their statues and sculptures vandalized and smashed, their ancient temples and monuments looted and destroyed, and their vast libraries holding centuries of accumulated wisdom and knowledge burnt to the ground, the precious works and advancements contained in them lost to history, and the people now weakened, tradition and social coherence obliterated, vulnerable to increasing miscegenation and the predations of hostile foreign outsiders, or to Christian-orchestrated purges and bloody mass executions. Ramsey Macmullen and J. N. Hilgarth elaborate on this violent, forced transition of Europeans to Christianity in the fourth to eighth centuries following Emperor Constantine’s proclamation that Christianity was now the one official religion of Rome.

Irving

Zero

Lebenskraft ! (10)

Dachau

Then I headed to Dachau, about 45 minutes from Munich. On the way I passed where the Gestapo had their offices. Here I am looking at the entrance and exit gates of the concentration camp:

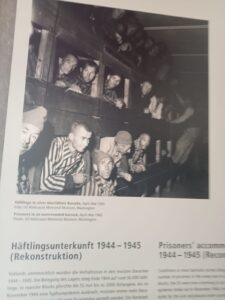

Previous generations of Germans weren’t as aggressively brainwashed as they are today. The person in charge of showing us the Dachau concentration camp, for example, had a mother who belonged to the Hitler Youth, and her father never talked about the war unless the beer got too much, she confessed. Nowadays, the System forces the adolescents to visit Dachau to indoctrinate them in anti-Nazi ideology, as we see in this picture I took:

The number of young people I saw in the camp was considerable! But in reality, Dachau wasn’t an extermination camp but a re-education camp for opponents of the Third Reich. It was a camp for males. Himmler was born very close to it, and when he came to power, he had the excellent idea of imprisoning the political opposition.

The camp operated from 1933 to 1945 and is now home to riot control units, which occupy many of Dachau’s buildings. Prisoners began arriving in 1933. Official figures put the number of detainees at 206,000 in the years the camp was active, and 42,000 who died there. The camp is huge: it covers 200 hectares and there is a plaque commemorating the ‘liberation’ perpetrated by the gringos in April 1945.

I am irritated to report that, on visiting the camp, the guide informed us that this month would be the 80th anniversary of the ‘liberation’ of Dachau, celebrated in a big way there.

In the 1930s there was a saying for dissidents, ‘Shut up if you don’t go to Dachau’. Nowadays people in power also incarcerate political dissidents, as evidenced by Joseph Walsh and Chris Gibbons serving a sentence of years and recently, also in England, twelve men were arrested for daring to celebrate Hitler’s birth, as an Englishman let us know today. The hypocrisy is so blatant that the Americans used Dachau for three years to imprison Germans!

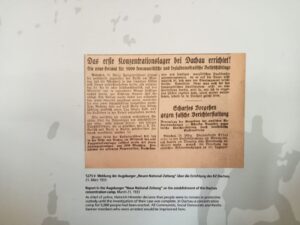

This sort of thing, naturally, is not denounced by official guides unlike Himmler, who announced in a newspaper why Dachau had been opened:

In some of the photos in the museum we can see who was imprisoned. For example, a clergyman said in a sermon that it was legitimate to assassinate a tyrant (Hitler). The mayor of Vienna also ended up in Dachau. After all, in real life he behaved as Captain Georg von Trapp behaved in The Sound of Music: an exception, because the Austrian people in general opened their arms to the Führer.

The camp also received commies and political prisoners from all over Europe, especially Poles and Russians, but also French, Germans, Czechs and Republican Spaniards.

I love the German bureaucracy that ordered everything and scrupulously classified the type of prisoner, as long as there was a hierarchy among them. Some crimes against the state or the race were considered much more serious than others.

The blue triangle designated migrants; the black triangle designated consumers of degenerate culture and also those who married Jews. These measures couldn’t be implemented in a new ethnnostate because virtually all Westerners would have to be imprisoned, even some white nationalists, as Sebastian Ronin mocked in one of his cartoons!

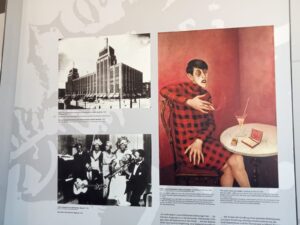

There were also colours for gypsies and political prisoners, red. Of course, consumers of degenerate culture fared much better in Dachau than, say, opponents of the regime, especially if they were Jews. But what does a consumer of degenerate culture mean? It should be obvious to today’s racialists that the Afro-American art is unfit for the Aryan spirit, as I saw on this museum poster:

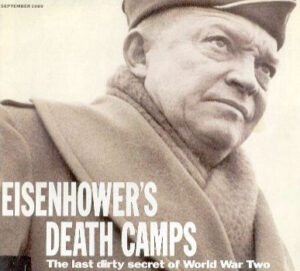

The chutzpa of the System never ceases to amaze me. In the conditions at Dachau, and remember that not every prisoner was treated equally but some were relatively well treated, just over forty thousand died according to official figures. Eisenhower murdered 800,000 Germans in real death camps!

Dachau was, as I said, a re-education camp where you could get out alive. In Eisenhower’s extermination camps no behaviour could save you: the object was to kill you for having been a National Socialist.

The barracks at Dachau were removed in the 1960s and now only the rows of poplar trees remain.

If you look closely at the picture above, in the background you can see the first memorial built for the ‘victims’ of the camp. It was not built by the Jews, but by Catholics: a church, built in 1964.

The church bells ring at 3 pm to commemorate the Catholic ‘saints’ and the ‘victims’ of Dachau. Behind it is a Carmelite monastery, built not long after. Next to it we can see the Lutheran church that was built later, commemorating the same thing.

The young people do voluntary service because the de-Nazification process never ends in Germany. Then the Orthodox Christians made their own monument: another propagandistic church. They even brought soil from Slavic soil because they didn’t want to build their church on German soil.

But you can also see the Jewish hand in Dachau in this memorial, as the first line is in Hebrew:

Then I saw the crematoria for those who died in the camp. According to the guide, who as I said her mother had been in the Hitler Youth, where this tree was, some of the prisoners were hanged:

It was strange to see beautiful women visiting the museum.

And a mixed couple was not to be missed.

The museum, the guided tours by guides who must be licensed by the German state, and all the culture and universities of Munich are a gigantic fraud. Munich, a city where only a few buildings are taller than the cathedral, is the publishing capital of Europe (only New York has more publishing houses), but what good is so much culture if they are incapable of publishing a book denouncing the Hellstorm Holocaust, like the one written by Tom Goodrich? The lie by omission is astronomical indeed, and the way the Establishment treats its authentic historians is shown by the following anecdote.

When Goodrich wrote Hellstorm he struggled to find a publisher in the US. So much so that, for a time, he was homeless (writers generally live from day to day, and a blow like not finding a publisher for the latest work can be fatal). Tom asked me not to reveal it as long as he lived.

But last year our friend passed away.

Future historian

I own the Holocaust Handbooks series on DVDs: the Holocaust deniers’ point of view.

On the other hand it is true what I said in previous posts: I also own a seminal treatise of almost fifteen hundred pages that represents, among others, the orthodox view in academia that the Holocaust was historical.

True, I have skimmed both versions, but obviously I won’t read all the material on either side!

To do so I would have to be fifty years younger and, moreover, an institution would have to pay for such research, whereas a fair hearing of the ‘deniers’ and ‘affirmers’ would take many years.

To give just one example. Some affirmers rely on German documents and testimonies of the alleged victims while some deniers physically analyse, say, the rooms where Zyklon-B was allegedly spread in Auschwitz’s gas chambers. A denier may rationalise away the evidence of documents and testimonies. At the same time, an affirmer may not answer the scientific analysis that a denier did in the gas chambers of Auschwitz.

Parallel universes are thus created in which there is no communication between the two groups.

Trying to break that from a neutral point of view requires not only youth, but also funds for research. It is not enough, one denier would say, that Mark Weber and David Irving—who starred in the denialist movement some decades ago—, have in their later years come closer to the position of the affirmers (because of German documents at the time of the Final Solution). The affirmers, it is said, have to refute point by point the deniers’ scientific and statistical analyses (the enormous volume of bodies that are claimed to have been incinerated in the extermination camps).

That can only be done by a neutral team without thoughtcrime laws, and research would take years. Even if I magically took half a century off my shoulders, and an academic institution gave me a grant to study the so-called Holocaust neutrally, I wouldn’t be able to produce convincing results. The claims of some deniers have to be honestly addressed and researched in labs by specialists in chemistry and the logistics of mass corpse cremation.

If the European system’s demand that I must believe the Holocaust as an article of faith or be thrown in jail is irrational, it is also irrational that I have to doubt it simply because there is the collection of denier books pictured above!

As I said, it would take not only decades but also a great deal of dedication from several historians and scientists to undertake teamwork and delve into this topic at an expert level.

I hope that, after the coming dollar collapse (and thus of the euro and all fiat currencies), the West will be liberated to such a degree that future generations of historians will be able to study the so-called Holocaust rationally.

It is always a pleasure to listen to Mark Weber, whom I mention in the most important article of this site, ‘The Wall’.

It is always a pleasure to listen to Mark Weber, whom I mention in the most important article of this site, ‘The Wall’.

Weber is a revisionist about the official story of the Second World War, Hitler and the Holocaust.

Criminal History, 199

For the context of these translations click here.

PDFs of entries 1-183 (several of Karlheinz Deschner’s

books abridged into two) can be read here and here.

Arnulf of Carinthia and Louis the Child by Johann Jakob Jung (1840).

The (German) drive eastwards

King Arnulf had a new palace built in Regensburg. The city had already been the central palace of Louis the German, a centre of the mission to the East, and of caravan trade with Bohemia, Moravia and Hungary—everything essentially Christian and Western world was concentrated here: the power of state, church and money. Regensburg became the city with which Arnulf (who often, like his father and grandfather, also visited the palaces of Ötting and Ranshofen) probably felt the closest connection, where a third of his charters were issued and held at least four imperial assemblies and numerous stays are attested. For researchers, this choice of his heartland not only reflects his past, ‘but also the emphasis on the tradition of Louis the German and the priority given to south-east policy, but also Arnulf’s keen sense of political realities’ (Störmer). In other words, the German urge towards the East, already evident in King Arnulf, is already clear.

Immediately after his coup d’état he retired to consolidate his position on his most important power base, now strong enough to easily suppress the attempted rebellion of his younger cousin Bernhard in Swabia. Bernhard (ca. 876-891/89), illegitimate like Arnulf, was the son of Emperor Charles III, who in 885 was unable to secure Bernhard as heir to the throne (just as Charles also failed to adopt Louis, son of Boso of Vienne and a Carolingian on his mother’s side, two years later). However, Bernhard, who sought to re-establish his father’s original kingdom, did not want to relinquish his rights to the throne even after Arnulf’s elevation to East Frankish king. In 889, he allied with nobles from Raetia and Alemannia, including Abbot Bernhard of St. Gall (then deposed by Arnulf). Still, he was killed a year later when Margrave Rudolf of Raetia defeated the Putsches.

Arnulf himself marched against the Abodrites in the late summer of 889 as the leader of a strong army, having met with his men and many bishops, including Sunderold of Mainz and Willibert of Cologne, in Frankfurt shortly beforehand. However, this time he was unable to achieve anything in the north and once again celebrated ‘the Lord’s birthday in Regensburg in a dignified manner’.

And he continued to go to church, go to war, pray and kill all the time. In particular, Arnulf intervened almost continuously in Moravia in the last years of the 9th century. He had made peace with it in 985, as it had gradually become too strong, and had even made Swatopluk the godfather of his son Zwentibold. But all this did not last long, and soon they returned to their usual mode of communication.

Tom

Editor’s Note: With the exception of replacing the word ‘is’ for ‘was’ (and a few other words of that phrase changed from present tense to past tense), the following text was sent to me by Thomas Goodrich himself when a few years ago I asked him what he wanted me to put in the Metapedia article about him:

______ 卐 ______

Born and raised in the American Mid-west, Goodrich was a professional writer who lived in Florida. In addition to numerous books devoted to the American Civil War and Abraham Lincoln, Goodrich has written several other highly popular works, including Scalp Dance—Indian Warfare on the High Plains, 1865-1879, Summer, 1945—Germany, Japan and the Harvest of Hate, and the ground-breaking book on World War Two, Hellstorm—The Death of Nazi Germany, 1944-1947.

Goodrich’s professional philosophy is simple:

My entire adult life has been devoted to the writing of unwritten history. As we all know, unless you learn from your history, you are doomed to repeat your history.

Thus, I have made it my life’s mission to give voice to history’s losers so that we might actually learn from our history, learn from both sides of our history, in the hope that we might thereby avoid repeating much of that history in the future.

From the American Civil War and Abraham Lincoln to World War Two I have chosen the loser’s perspective in my books simply to find out what is mostly unknown and hence, find out what is almost entirely unwritten. Winners do indeed write history and the libraries are full of the winner’s accounts.

I write that one book, that one book which will hopefully help us to not only understand and learn from the “other side,” but will hopefully help us to understand and learn what real history is. Only by understanding both sides of history can we hope to avoid repeating that very history we would prefer to avoid.

As soon as I can afford it, I’ll order a copy of his book Scalp Dance.

Tom was what I’ve called a ‘three-eyed raven’ on this site, in the sense that he saw the historical past as only the greenseers in Martin’s fiction could. And that was because, like Bran the Broken, Tom was abused as a child.

Only those who are knocked off the tower by their parents or guardians and become disabled, but are survivors, are able to cross the Wall in search of the raven. And Tom was one of the very few greenseers in all of Westeros (in the TV series, only Bloodraven held the title of three-eyed crow, and when the old man died that title was inherited by Bran).

Criminal History, 198

For the context of these translations click here.

PDFs of entries 1-183 (several of Karlheinz Deschner’s

books abridged into two) can be read here and here.

Arnulf storming the Norman defences on the River Dyle, 891 (engraving).

‘… a battle cry to the heavens’

Arnulf, who had been characterised by the battles in the south-eastern Marches, had been entrusted with the administration of the old Slovenian duchy of Carinthia, his actual power base in the east, by his father, the Bavarian king Carloman, shortly after 876 after the removal of several border counts; hence his nickname ‘of Carinthia’. However, while he was able to expand in Lower Pannonia, he initially failed (with his paralysed father) in the northern Danube region due to opposition from within Bavaria. His opponents, first Count Ermbert of Isengau, then Margrave Aribo, won the support of Arnulf’s powerful relatives, Louis the Younger and Charles III the Fat, his father’s brothers, who were able to assert themselves in Bavaria.

After all, Arnulf had learnt political tactics, he had learnt to bide his time and, of course, to fight. He had proven himself as a warhorse, including at Elsloo in 882 as commander of the Bavarian army against the Normans, where he had admittedly been unable to achieve anything. At the same time, he defeated them in mid-October 891 at Leuven on the Dyle (now Belgium). Incidentally, this was a declared act of revenge. Shortly before, in June, an ‘army of Christians, oh pain, as a result of his sins’ had been defeated at the Geule and one of the army leaders, Archbishop Sunderold of Mainz, appointed by Arnulf, had fallen (Regino von Prüm).

But now, at the Dyle, ‘God gave them strength from heaven’. This was obvious as the Alemanni, who had also been mobilised, had previously turned back with excuses and ‘crept back home from the king’. But how pithily he urged ‘the noble lords of the Franks’: ‘You men, since you honour the Lord and have always been invincible when you have defended your homeland under God´s grace, take courage when you think of avenging the pious blood of your parents that has been shed against your enemies, who after all are quite pagan and frenzied… Now, warriors, now that you have the criminals themselves before your eyes, follow me… Not to avenge our dishonour, but that of the Almighty, we attack our enemies in God´s name’ (Annales Fuldenses).

The pious Franks now ‘raised a battle cry to heaven’ and were promptly answered, which is not always the case. But now that ‘the Christians were attacking with murder’, they threw the pagans ‘in heaps’ into the river, ‘by the hundreds and thousands… so that their corpses dammed up the water’ [emphasis added by Ed.]. Two kings, Siegfried and Gottfried, were killed, sixteen royal standards were sent to Bavaria in triumph and processions were ordered. Arnulf himself ‘marched with the whole army, singing praises to God, who gave such victory to his own…’

For, yes, indeed, only uno homine had lost the Christian side (what a devil that must have been!), but the other tanta milia hominum Catholic historiography! There were ‘criminals’ there but at the same time, as the annalist proudly emphasises to enhance his achievement, ‘the Danes fought, the bravest of the Normans’, who had ‘never before’ been defeated in an entrenchment. For centuries, people in Leuven celebrated this marvellous victory, since the Normans had at least spared the East Frankish Empire (a final raid to Bonn and Prüm the following year aside).

It was a marvellous year in general.

For in 891, when Bishop Embricho of Regensburg died old and ‘happy’, Regensburg also burned down: ‘by divine vengeance, suddenly and miraculously engulfed in flames, burned on 10 August with all buildings, including churches, except the house of St. Emmeram the Martyr and the church of St. Cassian, which, although located in the middle of the city, were protected against the fire by God’. There, divine vengeance devoured (almost) the entire city, including churches; there, however, two church buildings were saved ‘for God’s sake’ (Annales Fuldenses).

O this marvellous work of the Lord!

‘The paths are often crooked and yet straight,

on which you let the children go to you;

there it often looks wondrous,

but in the end your high counsel triumphs.’