Hitler was born on 20 April 1889, i.e. he was a year younger than my paternal grandmother, with whom I lived for a while (that means that if it hadn’t been for the Allied dogs, I might even have met him!). He was born in Braunau am Inn in Austria. Hitler would later call himself a Bavarian on several occasions.

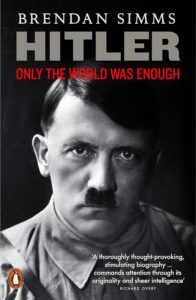

At the beginning of the first part of his book, Brendan Simms informs us that the first three decades of Hitler’s life were characterised by obscurity and various deprivations; his father and mother died, the latter after a traumatic illness, and his artistic talent went unrecognised in Vienna. Those were times, and we are talking before his twenty-fifth birthday, when the young Adolf didn’t yet show any signs of politicisation.

Today I can say that of all the post-1945 writers, I have the closest rapport with Savitri Devi—by far. But before I discovered white nationalism, and I’m talking about how I thought from 2002 to 2009, Alice Miller, the first author in history to take the side of the child abused by his parents was, intellectually, my Beatrice. It’s interesting what Simms says at the beginning of his biography: that there is no evidence that Alois, Hitler’s father, was violent to his children; because Miller, who suffered in the Warsaw ghetto, defamed Hitler by speculating that he had indeed been abused by his father Alois.

Hitler had an older half-brother, Alois Junior, and a half-sister, Angela, born from his father’s first marriage. After the death of his first wife, Alois married his cousin Klara Pölzl, with whom he had six children, only two of whom survived: Adolf himself and his younger sister Paula. Two of Hitler’s four siblings died before they were born, and another when Hitler was ten years old.

At school, the boy Adolf only got good marks in drawing and sport, but he was such a bad student that he failed one year before leaving school for good at the age of sixteen, about the age at which I, too, left school and for the same reasons (it’s all brain-washing bullshit what the System teaches us there). Simms informs us:

Hitler’s main preoccupations after leaving school were his financial security, his emotional life, pursuing a career as an artist and the health of his mother. The first known letter by Hitler was penned in February 1906, together with his sister Paula, asking the Finanzdirektion Linz for payment of his orphan’s pension.

I will be omitting the numbers and endnotes throughout my quotations of Simms’ book.

He visited Vienna on a number of occasions and soon moved to the imperial capital. There he pursued an interest in the operas of Richard Wagner. In the summer of 1906, Hitler saw Tristan and Isolde as well as The Flying Dutchman. He also attended the Stadttheater. He was engrossed by not only the music but especially the architecture of opera. A postcard of the Court Opera House Vienna records that he was impressed by the ‘majesty’ of its exterior, but had reservations about an interior ‘cluttered’ with velvet and gold.

I know that many visitors find it bothersome that, whenever I can, I take the opportunity to denigrate white nationalism. But I must. Savitri hits the nail on the head in her book when she points out that the Hitler phenomenon can only be understood if we see that he was a kind of initiate. And the initiation was art! It seems easy for me to understand this because, coming from parents who were artists, it seems obvious to me that this is what motivated me to seek a different path from the crap that conventional schooling offers us (everything looks like pork to someone who understands Beauty as a child). In other words, if contemporary racialists fail to initiate themselves into art, they won’t be able to save their race. I will not repeat Savitri’s reasons: that is why we abridged her book and translated that abridged version here. Simms continues:

In early 1907, Hitler’s mother was diagnosed with cancer and operated on without success. She had no medical insurance, but bills were kept low by the kindness of her Jewish doctor, Eduard Bloch. Hitler helped to look after his mother during her illness and he seems to have been devastated by her death in late December 1907.

He was eighteen years old.

It is certain, in any case, that Hitler neither blamed Bloch for his mother’s death nor became an anti-Semite in consequence. On the contrary, he remained in friendly contact with Bloch for some time after and even sent him a hand-painted card wishing him happy new year. Much later, Hitler enabled Bloch to escape from Austria on terms far more favourable than those granted for his unfortunate fellow Jews.

The young Hitler’s interests were above all musical and architectural, like the layout and architecture of Linz. He confessed to leading a hermit’s life and was plagued by bedbugs. These were times when he was on good terms with August Kubizek, another teenager. Savitri recounts some very revealing anecdotes of this friendship in her book. Simms ignores them in his biography Hitler, although he writes the following:

He certainly seems to have experienced a period of poverty, telling Kubizek that ‘you don’t have to bring me cheese and butter anymore, but I thank you for the thought’. He was not too poor, however, to miss a performance of Wagner’s Lohengrin.

Shortly, afterwards, Hitler left the Stumpergasse and was swallowed up by the city for more than a year. He lodged with Helene Riedl in the Felberstrasse until August 1909. His only known activity during this period was a second and equally unsuccessful application to the Academy. Hitler then lived for about a month as a tenant of Antonia Oberlerchner in the Sechshausterstrasse, leaving in mid September 1909. Even less is known about what came next. He certainly underwent some sort of economic and perhaps psychological crisis, leading to a descent from respectability.

Der Hauptplatz in Linz

A few years later, well before he was famous, Hitler told the Linz authorities that the autumn of 1909 had been a ‘bitter time’ for him. According to a statement he gave to the Vienna police in early August 1910, he spent a time in a sanctuary for the homeless at Meidling. How Hitler extricated himself is not known, but he was able to pay for a bed at the more respectable men’s hostel in the Meldemannstrasse in Vienna-Briggitenau from February 1910. There he started to paint postcards and pictures which his crony and ‘business’ partner Reinhold Hanisch would sell to dealers; this relationship soured when he reported Hanisch to the authorities for allegedly embezzling some of the money.

Now that I posted a review of The Godfather, I’ve been watching videos about the real-life mafia. One YouTubber said that what these people really loved was the American dollar. Those gangsters were slaves to Mammon, just like Hitler (and I) are slaves to the Goddess of Beauty. Simms ends his first chapter with some of these passages:

All we know for sure is that Hitler had to mark time in the Austro-Hungarian Empire until he was twenty-four so as to keep collecting his orphan’s pension. It did not help that he fell out with his half-sister Angela Raubal over their inheritance, and was forced to give way after a court appearance in Vienna in early March 1911…

In the spring of 1913, Hitler collected the last instalment of his pension. There was nothing to keep him in Vienna. When Hitler went to Munich in May 1913 his worldly possessions filled a small suitcase…

He lived happily for nearly a year under the roof of Czech spinster, Maria Zakreys, and betrayed no irritation at her limited command of German. His documented interests were architecture, town planning and music, particularly the connections between them. There was surely much more going on inside his head, but we cannot be certain what it was.

Hitler’s self-description varied, but the common denominator was creativity. He registered himself as an ‘artist’ in the Stumpergasse in mid February 1908, as a ‘student’ in the Felberstrasse in mid November 1908, as a ‘writer’ in the Sechshausterstrasse in late August 1909, and as a ‘painter’ at the Meldemannstrasse in early 1910 and again in late June 1910…

He was eventually mustered in Salzburg by the Austrian authorities, in early February 1914, and found to be physically unfit to serve. In the meantime, Hitler continued to make his living by selling pictures, just as he had in Vienna.

All this makes our picture of the young Hitler closer to a sketch than a full portrait. To be sure, he was already more than a mere cipher: his artistic interests were already well established; his hostility to the Habsburg Empire, though not the reasons for it, was a matter of record… There is no surviving contemporary evidence that he was much aware of France or the Russian Empire or the Anglo-World of the British Empire and the United States. That was about to change. If the Hitler of 1914 had as yet left almost no mark on the world, the world was about to make his mark on him.