The fourth part of El Grial begins with a dream that I now translate into English:

I was walking on a street by day next to Dad, who pointed out to me, enthusiastic and joyful as his character, the great church—or wall of a great church, rather like a Gothic cathedral—while I felt real horror for the (not glimpsed, only felt) kind of gargoyles, low relief sculptures or external figures of a very dark-stone cathedral. The contrast between the spirited Dad in pointing out to me that Christian bastion as something so positive that he even smiled at me and the horrified son—although I corresponded to Dad’s smile from my height as a child with another smile to be nice with him—couldn’t be greater.

Then I commented that over the years I had several dreams with that theme. I interpreted that my father lacked enough empathy to realise that traditional Catholic doctrine, which seemed so positive to him, horrified his little firstborn.

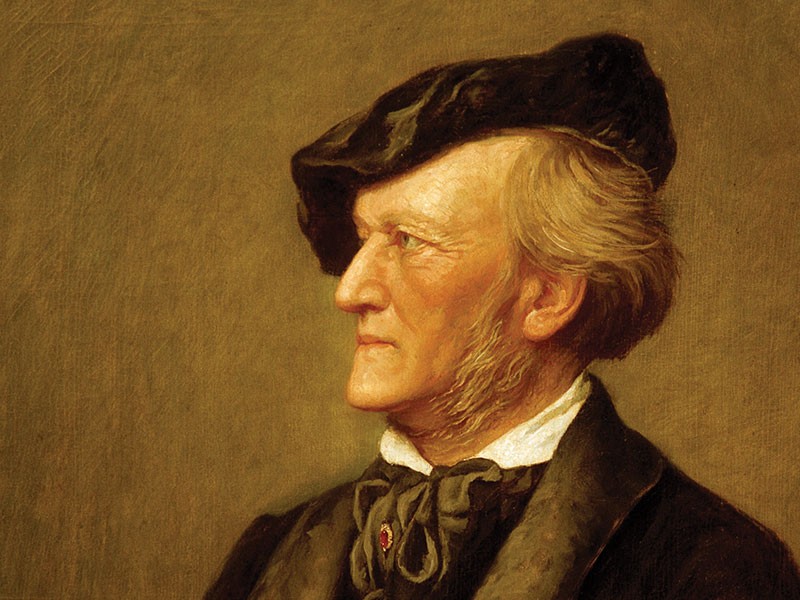

I recently said that Parsifal’s music has been one of my favourites, despite the fact that the opera characters are quasi-Christian knights that Wagner devised. Wagner’s last opus is not a hundred percent Christian insofar the script never names Christ or Christianity. Rather, it resembles the spirit of the Germanic sagas in times of Christian conversion, when something of the ancient pagan spirit was still breathed. In this first entry about how I contrast Wagner with Bach I confess that, unlike Parsifal, traditional Christian music has horrified me as much as that series of dreams with which I opened this post.

Iconoclasm, even in music, is a thorny topic. If we proclaim the transvaluation of all values the question immediately arises: What to do with the so-called sacred music after the anti-Christian revolution conquers the world? We have already seen that Nietzsche loved Parsifal’s music but abhorred its message, especially the chastity of the quasi-Christian knights. In my opinion, Wagner, Hitler’s favourite composer, is salvageable but how should we treat sacred music from his predecessors?

Unlike Richard Wagner (1813-1883) who flourished a century after the death of Johann Sebastian Bach (1685-1750) Bach had no passion for the Germanic sagas of the pagan past. On the contrary: Bach composed his music for the main Lutheran churches in Leipzig, and adopted Lutheran hymns in his vocal works. The hundreds of sacred works that Bach created are generally seen as a manifestation not only of his craft, but of his great devotion to the god of Christians: the very god of the Jews. Bach even taught Luther’s catechism as Thomaskantor in Leipzig, and some of his pieces represent it. For example, his very famous St Matthew Passion, like other works of this type, illustrates the Passion of (((Christ))) directly with biblical texts.

Compare all this with Wagner’s relatively paganised work who didn’t quote the gospel: a musician who, by introducing pre-Christian elements in his operas, was already starting to shake off the Judeo-Christian monkey from his back. But before continuing my talk about Bach I would like to quote, once again, the words of Nietzsche that appear in The Fair Race:

§ 61

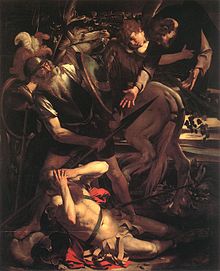

Here it becomes necessary to call up a memory that must be a hundred times more painful to Germans. The Germans have destroyed for Europe the last great harvest of civilisation that Europe was ever to reap—the Renaissance. Is it understood at last, will it ever be understood what the Renaissance was?

The transvaluation of Christian values: an attempt with all available means, all instincts and all the resources of genius to bring about a triumph of the opposite values, the more noble values… To attack at the critical place, at the very seat of Christianity, and there enthrone the more noble values—that is to say, to insinuate them into the instincts, into the most fundamental needs and appetites of those sitting there…

I see before me the possibility of a heavenly enchantment and spectacle: it seems to me to scintillate with all the vibrations of a fine and delicate beauty, and within it there is an art so divine, so infernally divine, that one might search in vain for thousands of years for another such possibility; I see a spectacle so rich in significance and at the same time so wonderfully full of paradox that it should arouse all the gods on Olympus to immortal laughter: Cæsar Borgia as pope!… Am I understood? Well then, that would have been the sort of triumph that I alone am longing for today: by it Christianity would have been swept away!

What happened? A German monk, Luther, came to Rome. This monk, with all the vengeful instincts of an unsuccessful priest in him, raised a rebellion against the Renaissance in Rome…

Instead of grasping, with profound thanksgiving, the miracle that had taken place: the conquest of Christianity at its capital—instead of this, his hatred was stimulated by the spectacle. A religious man thinks only of himself. Luther saw only the depravity of the papacy at the very moment when the opposite was becoming apparent: the old corruption, the peccatum originale, Christianity itself, no longer occupied the papal chair! Instead there was life! Instead there was the triumph of life! Instead there was a great yea to all lofty, beautiful and daring things!

And Luther restored the church.