I don’t see Christianity as a big problem because our racially-conscious ancestors… had no illusion about race at all. They care very much about the salvation of the souls of their slaves… building Sunday schools for black people. —Joel Webbon

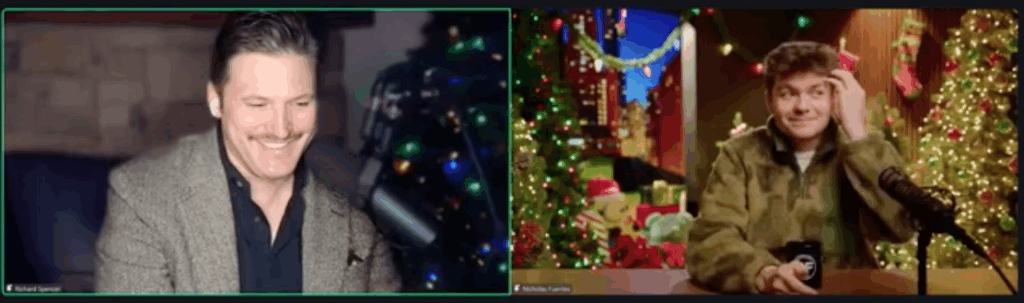

Since Jared Taylor is the son of pious Christians who tried to evangelize the Japanese, and Joel Webbon is a Christian Nationalist, after the twelfth minute of the interview (linked below) neither believes in the malice of politicians in recent decades for bringing millions of non-whites to the West. I, on the other hand, not only blame the politicians but also this pair for following the commandment to love your neighbour (for example: these politicians) instead of openly hating those who have brought the orcs to Nordid lands.

A couple of minutes later, Webbon asks Taylor why only whites are susceptible to bringing coloured people to their lands. What an incredible lack of insight: it’s your proclaimed Calvinist faith that originated the problem (I recently recommended Tom Holland’s Dominion and I recommend it again). It’s curious that Webbon uses the term “suicidal toxic empathy” without realizing that it comes directly from the gospel.

Taylor responds that a hundred years ago Americans weren’t ethno-suicidal. He thus ignores the fact that the cancer of Judeo-Christian values only metastasized after 1945. In his country, the process had already begun with Washington’s 18th-century presumption of not being anti-Semitic, and even more so with the Quaker ideology of the 19th century, which infected the American collective unconscious to such a degree that it led to the deaths of countless Southerners in a civil war in which the villains of our story triumphed.

In Taylor’s response, it’s also noticeable that—like everyone on the American racial right—he doesn’t talk about Latin America, even though they began their ethno-suicidal process on the Iberian Peninsula with Moors and converted Jews. And let’s not even mention how those peninsular Spaniards procreated with Indigenous women on the American continent (the case of the Portuguese was even worse: with Negroes in Lisbon itself). By focusing on the US, their view of the West is myopic.

Then Taylor begins to talk about democracy, the rights of the weak, respect for women, and freedom of speech as qualities exclusive to white people: another example of myopia. Once again, this pair is telling history from the perspective of Christendom, ignoring the Greco-Roman, Viking or Indo-European worlds. Taylor cites Angela Merkel’s decision to allow millions of Syrians into Europe as an example. I don’t want to repeat what Holland said on the subject and how he located the aetiology of Angela’s deed in Christianity (see pages 154-156 on Angela in Holland’s text in our abridged version of his book, Neo-Christianity, linked in our featured article).

Then Taylor mentions those who blame Christianity and intermarriage, adding: “All of this perversion of Christianity” referring to Woke culture. Note that although it is true that it is a perversion of traditional Christianity, it doesn’t answer the argument of Nietzsche, Holland and others: that Christianity gave birth to liberalism (which we call neochristianity).

Then Taylor mentions those who blame Christianity and intermarriage, adding: “All of this perversion of Christianity” referring to Woke culture. Note that although it is true that it is a perversion of traditional Christianity, it doesn’t answer the argument of Nietzsche, Holland and others: that Christianity gave birth to liberalism (which we call neochristianity).

Webbon replies that he’s pleased with what Taylor said because, as a Baptist Christian, he doesn’t believe we should blame his religion. He repeats the typical clichés of white nationalists: that if Christianity were guilty, how would we explain the Crusades? (Tip: the Crusades weren’t undertaken out of racial passion: a pope called the First Crusade to defend the interests of the Church.) Shortly after, he adds that Christians centuries ago recognized that peoples were different, but omits that the Church—unlike the Visigoths before their conversion—permitted mixed marriages. Even El Cid didn’t revert to the healthy racism of a millennium earlier, during the time of the Visigoths in Hispania: at one point in his life, El Cid even worked for a powerful Moor.

Then Webbon and Taylor discuss Hitler and the Holocaust in a way that could be called “fair enough.” But they should read Holland, who argues that the new axiology that demonizes Hitler is neochristian, albeit atheist (for those who are too lazy to read his book, there are a huge number of people interviewing Holland on YouTube).

After elaborating on the above, Webbon argues that Christianity would solve the guilt problem afflicting white men today. He doesn’t seem to realize that this guilt was precisely induced by Christian values, and this is especially evident in the post-WWII consensus. As our friend Joseph Walsh said, that consensus represented the ultimate triumph of gospel values, so much so that atheists especially embraced them with fierce fanaticism.

Then Taylor returns to the anti-Christian position that blames the religion of our forefathers and says that as the West becomes less Christian, it becomes more ethno-suicidal. This ignores two things: (1) before Constantine, ethno-suicide was accidental, for example, miscegenation in the late and decadent Roman Empire, not an explicitly anti-white ideology and (2) the same old story: he is ignorant of books like Dominion, which demonstrate how traditional Christianity metamorphosed into atheistic neochristianity.

Then Webbon says that in his American utopia, the government and voters could only be Christian. So, would people like William Pierce and Revilo Oliver be second-class citizens?

Elaborating on what Webbon calls Christian Nationalism, he says that whites are incapable of understanding themselves as a collective. He ignores (1) that in pre-Christian times, the pure Nordics who conquered India, Sparta, the early Romans and the Visigoths considered themselves a group, and that (2) it was precisely the threat of eternal damnation for those who didn’t worship the god of the Jews that fell upon the Aryan collective unconscious like an atomic bomb: it atomized it, turning whites into “individuals,” “souls” whose priority was to save themselves from the torments of hell.

The only good thing about Webbon’s American utopia is that he wants a return to traditional patriarchy. At a crucial moment, Taylor asks him if, in his ideal America, a morally upright black Christian could vote, but not a non-Christian white. Webbon replies that, indeed, only that black could vote.

Webbon then presents Taylor with a thought experiment: if one of them were king, how would the culture be better? But he cheats: because the thought experiment begins without specifying how one hundred million non-whites would be “deported” from the US to the point that only 20% of the population would remain non-white. Since the experiment begins this way, the dishonesty lies in Webbon’s avoidance of scenarios like The Turner Diaries, where an anti-Christian morality is needed to carry out such a massive deportation (or extermination, in the case of the novel).

This would be my response to the “If I Ran the Zoo” scenario. I would threaten that remaining 20% to leave within four months, or else every non-white man, woman and child seen on the street would be shot on the spot.

Simple.

However, Webbon understands better why feminism is so toxic than most of the racialists I’ve seen online (and Taylor more or less agrees with him on this). But shortly after, Webbon says it would be atrocious not to properly feed a quadriplegic child. My response: a society of exterminating soldiers would resemble that of the Spartans.

A few minutes later, Taylor again commits a fallacy that I had already detected before. He said that he focuses on race, and that’s why he doesn’t want to have other battlefronts like feminism, the JQ, or Christianity. The fallacy lies in the fact that all these issues are interconnected with preserving the race. Let’s remember the slogan “transvaluation of all values.” It’s impossible to focus exclusively on race without taking away the power of non-reproduction from women today. Without transvaluing that value to the patriarchy of the past, spoiled gals would continue to drive the Aryan race to extinction since they don’t want to have many children. The same could be said of Christianity, the idealization of homosexuality, the anti-Nordicism in vogue on the American racial right and so on. Only the dissident who realizes that all these are facets of the same geometric figure is ideologically cleansed of ethno-suicide.

In other words, Taylor claims he doesn’t want to antagonize so many whites because what we need most is to work together. But he doesn’t realize that even the racial right is ethno-suicidal, as I have shown on this site. More than once I have used the metaphor that the post-WWII zeitgeist is similar to a train with Jews and ultra-liberal whites in the two main driver’s seats, accelerating the train toward the precipice. American conservatives are like a secondary co-pilot who applies the brakes here and there, slowing the train down, but not stopping it. White nationalists have gotten off the train, but faithful to Christian morality, they continue along the same route, albeit on foot, toward the precipice. They will take longer than those on the train, but the neochristian mandate that everyone obeys is to head for the precipice (to understand my metaphor I would suggest reading my anthology, Daybreak).

Taylor assumes that his ideology is not headed for disaster. But it’s clearly headed there, since he has never repudiated the Christian ethics of his parents. Then he says he is against those racists who say that if someone is Christian, he “cannot run for office.” Once again: Taylor ignores the fact that a Christian would never dare to expel the Jews from their country, or even scare them into leaving by opening Auschwitz II. (Furthermore, to achieve this, Taylor would not only have to repudiate Christian morality, but also the ideology of the Founding Fathers he so admires.) With presidents who submit to Christian morality, the Jewish problem will never be solved. In fact, we could see Webbon as a traditional Christian and Taylor as what we call a neochristian.

Webbon then discusses the New Testament, and it’s clear his Protestantism is essentially fundamentalist: he takes all the great miracles as historical, such as the resurrection, Jesus’ ascension into the clouds, and the Great Commission (those who still believe all of that should read NT scholar Richard C. Miller).

Shortly after, Webbon says something that perfectly illustrates my point: that Christians who sympathize with racialism are headed for disaster. He says that in the society he envisions, there would be no laws against a Negro marrying a white woman!

Near the end of the interview, Webbon mentioned that an early Protestant theologian held Constantine in such high esteem that he invoked the biblical commandment to honour one’s parents and ancestors (that is, even the first Christian emperor). Compare this to what Karlheinz Deschner says about Constantine in the book we’ve summarized.

A few minutes later Taylor said he, too, would oppose banning interracial marriage!

Do you finally understand why the Führer’s way is the only way? And why, in practical terms, fundamentalist Christianity and secular neochristianity are two sides of the same coin?

I didn’t watch the rest of the program because Taylor very politely left shortly after saying that, and Webbon began discussing his interview with two professed Christians.

These days I’ve been reading a printed copy of Them and Us, which I used last year in its Kindle version for my excerpts from that book.

These days I’ve been reading a printed copy of Them and Us, which I used last year in its Kindle version for my excerpts from that book.