Editors’ note:

Editors’ note:

To contextualise these translations of Karlheinz Deschner’s encyclopaedic history of the Church in 10-volumes, Kriminalgeschichte des Christentums, see the abridged translation of Volume I (here).

The Christian Book Burning

and the Annihilation of Classical Culture

Where is the wise person? Where is the educated one? Where is the philosopher of this age? Has not God made foolish the wisdom of the world?

—St. Paul, I Corinthians 1:20

Charlatanism is initiated among you by the schoolteacher, and as you have divided the science into parts [sacred & profane], you have moved away from the only true one.

—Tatian

After Jesus Christ, all research is already pointless. If we believe, we no longer demand anything that goes beyond our faith.

—Tertullian

If you want to read historical narratives, there you have the Book of The Kings. If, on the contrary, you want to read the wise men and philosophers, you have the prophets… And if you long for the hymns, you also have the psalms of David.

—Apostolic Constitution (3rd Century)

Religion is, therefore, the central core of the entire educational process and must permeate all educational measures.

—Lexicon for Catholic Life (1952)

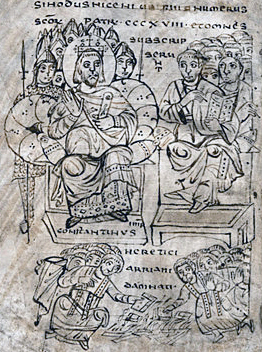

Constantine ordered to burn the fifteen books of the work Against the Christians written by Porphyry, the most astute of the opponents of Christianity in the pre-Constantinian era: ‘The first state prohibition of books decreed in favour of the Church’ (Hamack). And his successors, Theodosius II and Valentinian III, condemned Porphyry’s work again to the bonfire, in 448. This happened after Eusebius of Caesarea had written twenty-five books against this work and the doctor of the Church Cyril nothing less than thirty.

Towards the end of the 4th century, during the reign of Emperor Valens, there was a great burning of books, accompanied by many executions. That Christian regent gave free rein to his fury for almost two years, behaving like ‘a wild beast’, torturing, strangulating, burning people alive, and beheading. The innumerable records allowed to find the traces of many books that were destroyed, especially in the field of law and the liberal arts. Entire libraries went to the fire in the East. Sometimes they were eliminated by their owners under the effect of panic.

On the occasion of the assaults on the temples, the Christians destroyed, especially in the East, not only the images of the gods but also the liturgical books and those of the oracles. The Catholic Emperor Jovian (363-364) had the Antioch library destroyed by fire: the same library installed there by his predecessor Julian the Apostate. Following the assault on the Serapis in 391, during which the sinister Patriarch Theophilus himself destroyed, axe in hand, the colossal statue of Serapis carved by the great Athenian artist Bryaxis, the library was consumed by flames.

After the library of the Museum of Alexandria, which already had 700,000 rolls, was consumed by a casual fire during the siege war by Cesar (48-47 BC), the fame of Alexandria as a city possessing the most numerous and precious bibliographic treasures only lasted thanks to the library of the Serapis, since the supposed intention of Antony to give Cleopatra, as compensation for the loss of the library of the museum, the entire library of Pergamum, with 200,000 rolls , does not seem to have come to fruition. The burning of libraries on the occasion of the assault on the temples was indeed something frequent, especially in the East.

It happened once again under the responsibility of Theophilus, following the destruction of an Egyptian sanctuary in Canopus and that of the Marneion of Gaza in 402.

At the beginning of the 5th century, Stilicho burned in the West—with great dismay on the part of the Roman aristocracy faithful to the religion of his elders—the books of the Sibyl, the immortal mother of the world, as Rutilius Claudius Namatianus complained. To him, the Christian sect seemed worse than the poison of Circe.

In the last decades of the 5th century, the libelli found there (‘these were an abomination in the eyes of God’—Rhetor Zacharias)—were burnt in Beirut before the church of St. Mary. The ecclesiastical writer Zacharias, who was then studying law in Beirut, played a leading role in this action supported by the bishop and state authorities. And in the year 562 Emperor Justinian, who had ‘pagan’ philosophers, rectors, jurists and physicians persecuted, ordered the burning of Greco-Roman images and books in the Kynegion of Constantinople, where the criminals were liquidated.

Apparently, already at the borderline of the Middle Ages, Pope Gregory I the Great, a fanatical enemy of everything classical, burned books in Rome. And this celebrity—the only one, together with Leo I, in gathering in his person the double distinction of Pope and Doctor of the Church—seems to have been the one who destroyed the books that are missing in the work of Titus Livy. It is not even implausible that it was he who ordered the demolition of the imperial library on the Palatine. In any case, the English scholastic John of Salisbury, bishop of Chartres, asserts that Pope Gregory intentionally destroyed manuscripts of classical authors of Roman libraries.

Everything indicates that many adepts of the Greco-Roman culture converted to Christianity had to prove to have really moved their convictions by burning their books in full view. Also, in some hagiographic narratives, both false and authentic, there is that commonplace of the burning of books as a symbol, so to speak, of a conversion story.

It was not always forced to go to the bonfire. Already in the first half of the 3rd century, Origen, very close in this regard to Pope Gregory, ‘desisted from teaching grammar as being worthless and contrary to sacred science and, calculating coldly and wisely, he sold all his works of the ancients authors with whom he had occupied until then in order not to need help from others for the sustenance of his life’ (Eusebius).

There is hardly anything left of the scientific critique of Christianity on the part of adherents to classical culture. The emperor and the Church took care of it. Even many Christian responses to it disappeared! (probably because there was still too much ‘pagan poison’ on its pages). But it was the classical culture itself on which the time came for its disappearance under the Roman Empire.

The annihilation of the Greco-Roman world

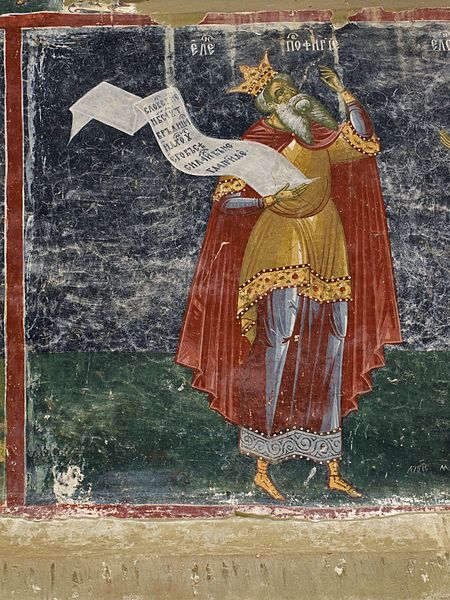

The last emperor of classical antiquity, the great Julian, certainly favoured the adherents of the old culture, but simultaneously tolerated the Christians: ‘It is, by the gods, my will that the Galileans not be killed, that they are not beaten unjustly or suffer any other type of injustice. I declare, however, that the worshipers of the gods will have a clear preference in front of them. For the madness of the Galileans was about to overthrow everything, while the veneration of the gods saved us all. That is why we have to honour the gods and the people and communities that venerate them’.

After Julian’s death, to whom the orator Libanius felt united by faith and friendship, Libanius complains deeply, moved by the triumph of Christianity and by its barbarous attacks on the old religion.

Oh! What a great sorrow took hold not only of the land of the Achaeans, but of the entire empire… The honours of which the good ones participated have disappeared; the friendship of the wicked and unbridled enjoys great prestige. Laws, repressive of evil, have already been repealed or are about to be. Those that remain are barely fulfilled in practice.

Full of bitterness, Libanius continues to address his co-religionists:

That faith, which until now was the object of mockery and that fought against you so fierce and untiring, has proved to be the strongest. It has extinguished the sacred fire, the joy of sacrifices, has ordered to savagely neat [its adversaries] and demolish the altars. It has locked the shrines and temples, if not destroyed them or turned them into brothels after declaring them impious. It has abrogated any activity with your faith…

In that final assault on the Greco-Roman world, the Christian emperors were mostly and for a long time less aggressive than the Christian Church. Under Jovian (363-364), the first successor of Julian, Hellenism does not seem to have suffered major damage except the closure and demolition of some temples. Also the successors of Jovian, Valentinian I and Valens, during whose government appears for the first time the term pagani referring the faithful of the old polytheism, maintained an attitude of relative tolerance toward them.

The Catholic Valentinian with plenty of reasons, because his interest was in the army and needed inner peace, tried to avoid religious conflicts. He still covered the high positions of the government almost evenly, even with a slight predominance of the believers in the gods.

Under Valens, nevertheless, the high Christian officials already constituted a majority before the Hellenes. Yet he fought the Catholics, even using the help of the Hellenes for reasons, of course, purely opportunistic.

Although the emperor Gratian, for continuing the rather liberal religious policy of his father Valentinian I, had promised tolerance to almost all the confessions of the empire by an edict promulgated in 378, in practice soon followed an opposite behaviour, for he was strongly influenced by the bishop of Milan, Ambrose.

Under Valentinian II, brother of Gratian, things really turned around and the relationship between high Christian officials and the adherents of the old culture was again balanced and the army chiefs, two polytheists, played a decisive role in the court. Even in Rome two other Hellenes of great prestige, Praetextatus and Symmachus, exerted the charges of praetorian and urban prefect respectively.

Gradually, however, Valentinian, as his brother once did, fell under the disastrous influence of the resident bishop of Milan, Ambrose. Something similar to what would happen later with Theodosius I. Ambrose lived according to his motto: ‘For the “gods of the heathen are but devils” as the Holy Scripture says; therefore, anyone who is a soldier of this true God must not give proof of tolerance and condescension, but of zeal for faith and religion’.

And indeed, the powerful Theodosius ruled during the last years of his term, at least as far as religious policy was concerned, strictly following Ambrose’s wishes. First, the rites of non-Christians were definitively banned at the beginning of 391. Later the temples and sanctuaries of Serapis in Alexandria were closed, which soon would be destroyed. In 393 the Olympic games were prohibited. The infant emperors of the 5th century [1] were puppets in the hands of the Church. That is why the court also committed itself more and more intensely in the struggle against classical culture, a struggle that the Church had already vehemently fuelled in the 4th century and that led gradually to the systematic extermination of the old faith.

The best-known bishops took part in this extermination, which intensified after the Council of Constantinople (381), with Rome and the East, especially Egypt, as the most notorious battlefields of the conflict between the Hellenes and the Christians.

___________

[1] Deschner is referring to emperors Arcadius, Theodosius II and Honorius whose reigns will be described in other translations of his books.

Editors’ note: To contextualise these excerpts of a 2-page section of Vol. II, ‘Theodosius II, Executor of All the Precepts of Christianity’ in Karlheinz Deschner’s encyclopaedic history of the Church in 10-volumes, Kriminalgeschichte des Christentums, read the abridged translation of Volume I.

Editors’ note: To contextualise these excerpts of a 2-page section of Vol. II, ‘Theodosius II, Executor of All the Precepts of Christianity’ in Karlheinz Deschner’s encyclopaedic history of the Church in 10-volumes, Kriminalgeschichte des Christentums, read the abridged translation of Volume I.