– For the context of these translations click here –

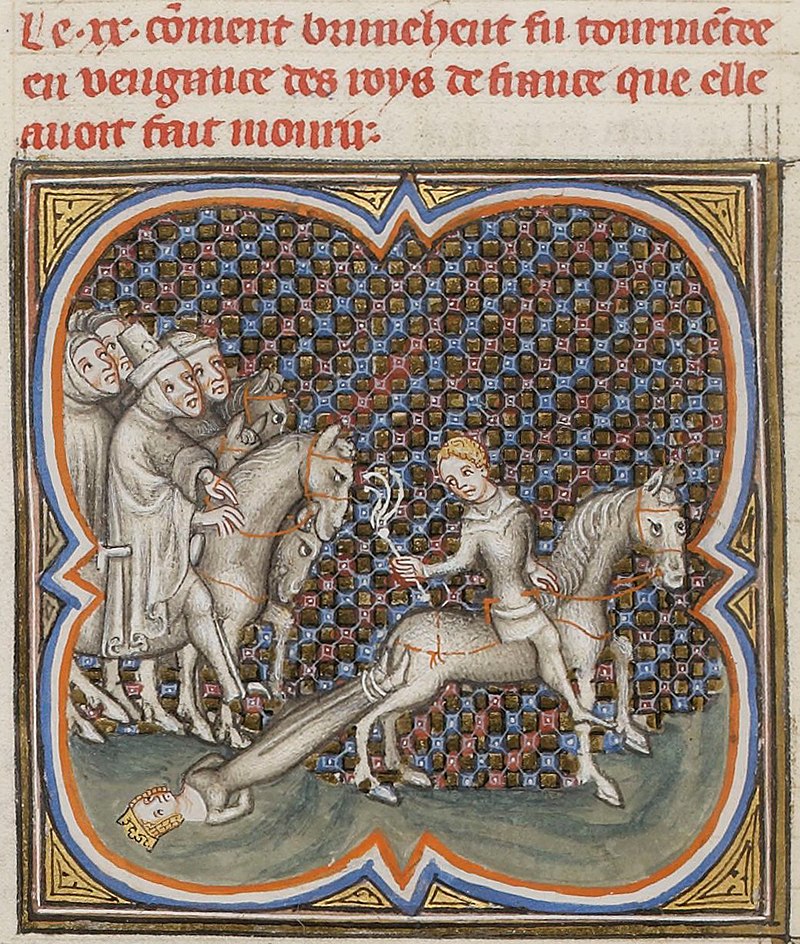

Miniature in the

Grandes Chroniques de France.

John VIII (872-882), a pope in his own right

Inspired by Gregory I and Nicholas I, his models, he took the directional role of the popes to an extreme. Just as Leo IV transformed St Peter’s, the Vatican quarter, the ‘Leonine City’, into a fortification, so John VIII walled up St Paul’s Basilica and the entire annexed suburb, which he called ‘Johannipolis’. And just as his predecessor—after having generously released Louis II from an oath issued through Duke Adelchis of Benevento in 871—had urged the emperor ‘to resume the struggle’ (Regino of Prüm), so also Pope John accompanied Louis’ war against the Saracens with vigorous biblical sentences and, as did Leo IV, absolved from their sins all those who ‘fall with Catholic piety against pagans and infidels’ and promised them the peace ‘of eternal life.’

This representative of Christ also recruited soldiers, obtained a Moorish cavalry from the King of Galicia, probably founded the office of president of the shipyards and probably in a ‘fresh initiative’ (Seppelt, Catholic) founded the first papal navy: ships occupied by troops, equipped with catapult machines capable of throwing stones, spears and hooks for boarding and moved by slave oarsmen. He was the first pope-admiral to go on the hunt for Saracens, managing to kill many of those ‘wild animals’—as he called them with the language of a true saintly father—and seize eighteen ships from Cape Circe. A ‘heroic deed,’ according to the Catholic Daniel-Rops. He was also determined to prevent any serious collaborationist contagion by threatening Christians who negotiated with the Saracens with ecclesiastical ex-communication.

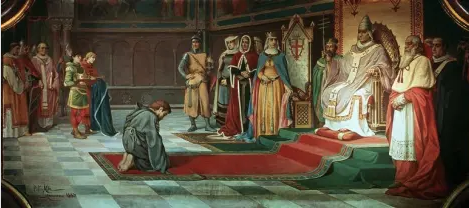

John VIII worked to destroy the empire and the kingdom of Italy to increase the power of his see, to dominate bishops and princes alike, and to direct Italy politically. ‘He who is to be raised by Us to the imperial dignity must first and foremost also be called and chosen by Us,’ he declared with astonishing boldness, while dazzling with the imperial crown, sometimes simultaneously, almost all possible candidates such as Boson of Vienne, the king of Provence, the sons of Louis the Germanic, Carloman and Louis III, and above all the West Frank Louis the Stammerer, son of Charles the Bald. And to each, he promised all exaltation, glory and salvation in this world and the next, all the kingdoms of the world. And to each he inculcated that he was the only candidate, claiming that in no other had he sought help and assistance! And when at last it was clear to him that he could not expect much from the Franks, he turned to Byzantium.

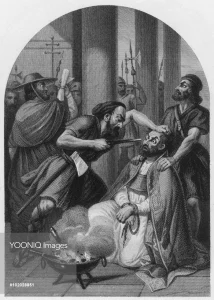

On 16 December 882, in a palace riot, a pious relative, who himself wanted to be pope and rich, poisoned him; but as the poison did not act quickly enough as the Annales Fuldenses report in brief but impressive words: ‘He struck him with a hammer until it stuck in his brain’ (malleolo, dum usque in cerebro constabat, percusus est, expiravit). It was the first papal assassination. And the example created a school.

While the Christians were thus attacking one another, not only in the narrow circle of the popes and not only in Italy, while their great ones were extorting money from one another, and while in the south they were robbing, killing and burning the Saracens, in the north the Normans were still present. Indeed, the Norman danger had grown worse. Even the Frankish king Carloman II asked in 884: ‘Is it any wonder that pagans and foreign peoples lord it over us and take away our temporal goods when each of us violently deprives his neighbour of the necessities of life? How can we fight with confidence against our enemies and those of the Church, when in our own house we keep the spoils stolen from the poor and when we go on a campaign to fill our bellies with stolen goods?’