Nine percent?

At the beginning of our century some Amazonian tribes continue the practice as horribly as described above. With the advances in technology we can even watch videos on YouTube about such practices, like children being buried alive.

At the beginning of our century some Amazonian tribes continue the practice as horribly as described above. With the advances in technology we can even watch videos on YouTube about such practices, like children being buried alive.

Let us remember the exclamation of Sahagún. The humble friar would have found it rather difficult to imagine that not only the ancient Mexicans, but all humanity had been seized by a passion for killing their little ones. Throughout his treatise on infanticide, Larry Milner mentioned several times that our species could have killed not millions, but billions of children since the emergence of Homo sapiens. At the beginning of his book Milner chose as the epigraph a quotation of Laila Williamson, an anthropologist at the American Museum of Natural History:

Infanticide has been practiced on every continent and by people on every level of cultural complexity, from hunter-gatherers to high civilizations, including our own ancestors. Rather than being an exception, then, it has been the rule.

Milner cowers in his book to avoid giving the impression that he openly condemns the parents. Before I distanced myself from deMause, in the Journal of Psychohistory of Autumn 2008 I published a critical essay-review of his treatise. My criticism aside, Milner’s words about the even more serious cowardice among other scholars is worth quoting:

As for the research into general human behavior, infanticide has been almost totally ignored. When acts of child-murder are referenced at all, they generally are passed off as some quirk or defective apparatus of an unusual place or time. Look in the index of almost all major social treatises and you will find only a rare reference to the presence of infanticide. […] Yet, the importance of understanding the reasons for infanticide is borne out by its mathematical proportions. Since man first appeared on earth about 600,000 years ago, it has been calculated that about 77 billion human babies have been born. If estimates of infanticide of 5-10 percent are true, then up to seven billion children [9 percent!] have been killed by their parents: a figure which should suffice as one of incredible importance.

Even assuming that this figure is contradicted by future studies, the anthropologist Glenn Hausfater would have agreed with Milner. In an August 1982 article of the New York Times about a conference of several specialists at the University of Cornell on animal and human infanticide, Hausfater said: “Infanticide has not received much study because it’s a repulsive subject. Many people regard it as reprehensible to even think about it…” In that same conference Sarah Blaffer Hrdy, a primatologist at Harvard said that infanticide occurs in all groups of evolved primates. Given the psychological limitations of academics, it is not surprising to see that the few who are not silent on the subject argue that the primary cause is economic. But the “economic explanation” does not explain why infanticide occurred equally among both the rich and the poor, or why it had been so frequent and sometimes even more frequent in the most prosperous periods of Rome and Carthage. The same is true about those seeking explanations about the taboos, superstitions and customs of the peoples, or the stigma attached to children born out of wedlock. None of these factors explains infanticide for the simple reason that modern Western societies have had these features and refrain from practicing it. Marvin Harris’s position is typical. Harris has calculated that among Paleolithic hunters, up to 23-50 percent of infants were put to death, and postulated that female infanticide was a form of population control. His colleagues have criticized him as a typical proponent of “environmental determinism.” If environmental determinism were true, there would have to be more sacrifice and infanticide today given the demographic explosion.

It is true that Milner fails to condemn the perpetrators. But despite his flaws, outlined in my 2008 review in deMause’s journal, the information Milner collected under a single cover is so disturbing that it made me think: What is really the human species? I have no choice but to try to ponder the question by analyzing one of the most horrendous forms of infanticide practiced over the centuries.

Historical Israel

In the past, the shadow of infanticide covered the world, but the Phoenicians and their biblical ancestors, the Canaanites, performed sacrifices that turn pale the Mesoamerican sacrifices of children.

The Tophet, located in the valley of Gehenna, was a place near Jerusalem where it is believed that children were burned alive to the god Moloch Baal. Later it became synonymous with hell, and the generic name “tophet” would be transferred to the sacrificial site of the cemetery at Carthage and other Mediterranean cities like Motya, Tharros and Hadrumetum, where bones have been found of Carthaginian and Phoenician children.

According to a traditional reading of the Bible, stories of sacrifice by the Hebrews were relapses of the chosen people to pagan customs. Recent studies, such as Jon Levenson’s The Death and Resurrection of the Beloved Son: The Transformation of Child Sacrifice in Judaism and Christianity have suggested that the ancient Hebrews did not differ much from the neighboring towns but that they were typical examples of the Semitic peoples of Canaan. The cult of Yahweh was only gradually imposed in a group while the cult of Baal was still part of the fabric of the Hebrew-Canaanite culture. Such religion had not been a syncretistic custom that the most purist Hebrews rejected from their “neighbor” Canaanites: it was part of their roots. For Israel Finkelstein, an Israeli archaeologist and academic, the writing of the book of Deuteronomy in the reign of Josiah was a milestone in the development and invention of Judaism. Josiah represents what I call one of the psychogenic mutants who firmly rejected the infanticidal psychoclass of their own people. Never mind that he and his aides had rewritten their nation’s past by idealizing the epic of Israel. More important is that they make Yahweh say—who led the captivity of his people by the Assyrians—that it was a punishment for their idolatry: which includes the burning of children. The book of Josiah’s scribes even promotes to conquer other peoples that, like the Hebrews, carried out such practices. “The nations whom you go in to dispossess,” says the Deuteronomy, “they even burn their sons and their daughters in the fire to their gods.” (12: 29-31). “When you come into the land that the Lord is giving you, you shall not learn to follow the abominable practices of those nations. There shall not be found among you anyone who burns his son or his daughter as an offering.” (18: 9-10).

This emergence, or jump to a higher psychoclass from the infanticidal, is also attested in other books of the Hebrew Bible. “The men from Babylon made Succoth Benoth, the men from Cuthah made Nergal, and the men from Hamath made Ashima; the Avvites made Nibhaz and Tartak, and the Sepharvites burned their children in the fire as sacrifices to Adrammelech and Anammelech, the gods of Sepharvaim” (2 Kings: 17: 30-31). There were kings of Judah who committed these outrages with their children too. In the 8th century B.C. the thriving king Ahaz “even sacrificed his son in the fire, following the detestable ways of the nations the Lord had driven out before the Israelites” (2 Kings 16: 1-3). Manasseh, one of the most successful kings of Judah, “burnt his son in sacrifice” (21:6). The sacrificial site also flourished under Amon, the son of Manasseh. Fortunately it was destroyed during the reign of Josiah. Josiah also destroyed the sacrificial site of the Valley of Ben Hinnom “so no one could use it to sacrifice his son or daughter in the fire to Molech” (23:10). Such destructions are like the destruction of Mesoamerican temples by the Spaniards, and for identical reasons.

Ezekiel, taken into exile to Babylon preached there to his people. He angrily chided them: “And you took your sons and daughters whom you bore to me and sacrificed them as food to the idols. Was your prostitution not enough? You slaughtered my children and made them pass through the fire” (Ezekiel 16: 20-21). The prophet tells us that from the times when his people wandered in the desert they burned their children, adding: “When you offer your gifts—making your sons pass through the fire—you continue to defile yourselves with all your idols to this day. Am I to let you inquire of me, O house of Israel? As surely as I live, declares the Lord, I will not let you inquire of me” (20:31). Other passages in Ezekiel that complain about his people’s sins appear in 20: 23-26 and 23: 37-39. A secular though Jung-inspired way of seeing God is to conceive it as how the ego of an individual’s superficial consciousness relates to the core of his own psyche: the Self. In Ezekiel’s next diatribe against his people (16: 35-38) I can hear his inner daimon, the “lord” of the man Ezekiel:

Therefore, you prostitute, hear the word of the Lord! This is what the Lord says: Because you poured out your lust and exposed your nakedness in your promiscuity with your lovers, and because of all your detestable idols, and because you gave them your children’s blood in sacrifice, therefore I am going to gather all your lovers, with whom you found pleasure, those you loved as well as those you hated. I will gather them against you from all around and will strip you in front of them, and they will see all your nakedness. I will sentence you to the punishment of women who commit adultery and who shed blood; I will bring upon you the blood vengeance of my wrath and jealous anger.

When a “prophet” (an individual who has made a leap to a higher psychoclass) maligned his inferiors, he received insults. Isaiah (57: 4-5) wrote:

Whom are you mocking? At whom do you sneer and stick out your tongue? Are you not a brood of rebels, the offspring of liars? You burn with lust among the oaks and under every spreading tree; you sacrifice your children in the ravines and under the overhanging crags.

The very psalmist complained that people sacrificed their children to idols. But what exactly were these sacrificial rites? The spoken tradition of what was to be collected in biblical texts centuries later complained that Solomon “built a high place for Chemosh, the detestable god of Moab, and for Molech, the detestable god of the Ammonites,” and that his wives made offerings to these gods (1 Kings 11: 7-8). And even from the third book of the Torah we read the commandment: “Do not give any of your children to be passed through the fire to Molech, for you must not profane the name of your God.” (Leviticus 18:21). A couple of pages later (20: 2-5) it says:

Say to the Israelites: “Any Israelite or any alien living in Israel who sacrifices any of his children to Molech must be put to death. The people of the community are to stone him. I will set my face against that man and I will cut him off from his people; for by giving his children to Molech he has defiled my sanctuary and profaned my holy name. If the people of the community close their eyes when that man gives one of his children to Molech and they fail to put him to death, I will set my face against that man and his family and will cut off from their people both him and all who follow him in prostituting themselves to Molech.”

Despite these admonitions, the influential anthropologist James Frazer interpreted some biblical passages as indicating that the god of the early Hebrews, unlike the emergent god quoted above, required sacrifices of children. After all, “God” is but the projection of the Jungian Self from a human being at a given stage of the human theodicy. Unlike Milner, a Christian frightened by the idea, I do not see it impossible that the ancient Hebrews had emerged from the infanticidal psychoclass to a more emergent one. In “The Dying God,” part three of The Golden Bough, Frazer draws our attention to these verses of Exodus (22: 29-30):

Do not hold back offerings from your granaries or your vats. You must give me the firstborn of your sons. Do the same with your cattle and your sheep. Let them stay with their mothers for seven days, but give them to me on the eighth day.

A similar passage can be read in Numbers (18: 14-15), and the following one (3: 11-13) seems especially revealing:

The Lord also said to Moses, “I have taken the Levites from among the Israelites in place of the first male offspring of every Israelite woman. The Levites are mine, for all the firstborn are mine. When I struck down all the firstborn in Egypt, I set apart for myself every firstborn in Israel, whether man or animal. They are to be mine. I am the Lord.”

The psychohistorian Howard Stein, who has written scholarly articles on Judaism since the mid-1970s, concludes in an article of 2009 that the gathered information suggests a particular interpretation. According to Stein, the substrate of fear for the slaughter “helps to explain the valency that the High Holiday have for millions of Jews worldwide,” presumably echoes of very ancient happenings: actual sacrifices by the Hebrews.

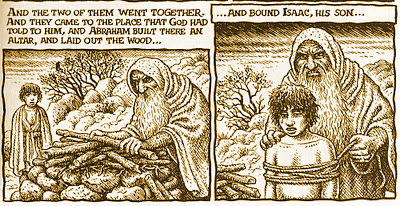

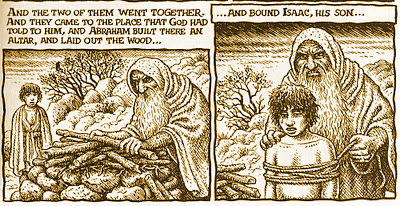

In contrast to what the evangelicals were taught in Sunday school as children, Moses did not write the Torah—it was not written before the Persian period. In fact, the most sacred book of the Jews includes four different sources. Since the 17th-century thinkers such as Spinoza and Hobbes had researched the origins of the Pentateuch, and the consensus of contemporary studies is that the final edition is dated by the 5th century B.C. (the biblical Moses, assuming he existed, would have lived in the 13th century B.C.). Taking into account the contradictions and inconsistencies in the Bible—for example, Isaiah, who belonged to a much more evolved psychoclass, even abhorred animal sacrifice—it should not surprise us that the first chapter of Leviticus consists only of animal sacrifices. The “Lord” called them holocausts to be offered at the entrance of the Tent of Meeting. After killing, skinning and butchering the poor animal, the priest incinerates everything on the altar “as a burnt offering to the Lord; it is a pleasing aroma, a special gift presented to the Lord.” A phrase that is repeated three times in that first chapter, it also appears in subsequent chapters and reminds me those words by Cortés to Charles V about the Mesoamerican sacrifices (“They take many girls and boys and even adults, and in the presence of these idols they open their chests while they are still alive and take out their hearts and entrails and burn them before the idols, offering the smoke as the sacrifice.”) In the book of Exodus (34:20) even the emerging transition of child sacrifice to lamb sacrifice can be guessed in some passages, what gave rise to the legend of Abraham:

For the first foal of a donkey, they should give a lamb or a goat instead of the ass, but if you do not give, you break the neck of the donkey. You must also give an offering instead of each eldest child. And no one is to appear before me empty-handed.

Compared with other infanticidal peoples the projection of the demanding father had been identical, but the emergency to a less dissociated layer of the human psyche is clearly visible. As noted by Jaynes, the Bible is a treasure to keep track of the greatest psychogenic change in history. The Hebrews sacrificed their children just as other peoples, but eventually they would leave behind the barbaric practice.

After captivity in the comparatively more civilized Babylon in 586 B.C., the Jews abandoned their practices. In his book King Manasseh and Child Sacrifice: Biblical Distortions of Historical Realities, published in 2004, Francesca Stavrakopoulou argues that child sacrifice was part of the worship of Yahweh, and that the practice was condemned only after the exile. Like their Christian successors, the Jews had sublimated their filicidal impulses in the Passover ritual. Each year they celebrate the liberation of their people and remember how Yahweh killed the firstborn Egyptians: legendary resonance of the habit of killing one’s eldest son.

But the biblical Moloch (in Hebrew without vowels, mlk), represented as a human figure with a bull’s head was not only a Canaanite god. It also was a god of the descendants of the Canaanites, the Phoenicians. The founding myth of Moloch was similar to that of many other religions: sacrifices were compensation for a catastrophe from the beginning of time. Above I said that Plutarch, Tertullian, Orosius, Philo, Cleitarchus and Diodorus Siculus mentioned the practice of the burning children to Moloch in Carthage, but refrained from wielding the most disturbing details. Diodorus says that every child who was placed in the outstretched hands of Moloch fell through the open mouth of the heated bronze statue, into the fire. When at the beginning of the 3rd century B.C. Agathocles defeated Carthage the Carthaginians began to burn their children in a huge sacrifice as a tactical “defense” before the enemy. The sources mention three hundred incinerated children. If I had made a career as a film director, I would feel obliged to visually show humanity its infamous past by filming the huge bronze statue, heated red-hot while the Greek troops besieged the city, gobbling child after child: who would be sliding to the bottom of the flaming chimney. In addition to Carthage, the worship of Moloch, whose ritual was held outdoors, was widespread in other Phoenician cities. He was widely worshiped in the Middle East and in the Punic cultures of the time, including several Semitic peoples and as far as the Etruscans. Various sacrificial tophets have been found in North Africa, Sicily, Sardinia, Malta, outside Tyre and at a temple of Amman.

Terracotta urns containing the cremated remains of children, discovered in 1817, have been photographed numerous times. However, since the late 1980s some Italian teachers began to question the historicity of the accounts of classical writers. Tunisian nationalists took advantage, including the president whose palace near the suburban sea is very close the ruins of the ancient city of Carthage. The Tunisian tourist guides even make foreigners believe that the Carthaginians did not perform sacrifices (something similar to what some ignorant Mexican tourist guides do in Chiapas). Traditional historians argue that the fact that the remains are from very young children suggests sacrifice, not cremation by natural death as alleged by the revisionists. The sacrificial interpretation of Carthage is also suggested by the fact that, along with the children, there are charred remains of lambs (remember the biblical quote that an evolved Yahweh says that the slaughter of sheep was a barter for the firstborn). This suggests that some Carthaginians replaced animals in the sacrificial rite: data inconsistent with the revisionist theory that the tophet was a normal cemetery. Furthermore, the word mlk (Moloch) appears in many stelae as a dedication to this god. If they were simple burials, it would not make sense to find those stelae dedicated to the fire god: common graves are not inscribed as offerings to the gods. Finally, although classical writers were staunch enemies of the Carthaginians, historical violence is exerted by rejecting all their testimonies, from Alexander’s time to the Common Era. The revisionism on Carthage has been a phenomenon that is not part of new archaeological discoveries, or newly discovered ancient texts. The revisionists simply put into question the veracity of the accounts of classical writers, and they try to rationalize the archaeological data by stressing our credulity to the breaking point. Brian Garnand, of the University of Chicago, concluded in his monograph on the Phoenician sacrifice that “the distinguished scholars of the ridimensionamento [revisionism] have not proven their case.”

However, I must say that the revisionists do not bother me. What I cannot tolerate are those subjects who, while accepting the reality of the Carthaginian sacrifice, idealize it. On September 1, 1987 an article in the New York Times, “Relics of Carthage Show Brutality Amid the Good Life” contains this nefarious phrase: “Some scholars assert, the practice of infanticide helped produce Carthage’s great wealth and its flowering of artistic achievement.” The memory of these sacrificed children has not really been vindicated even by present-day standards.

The Carthaginian tophet is the largest cemetery of humans, actually of boys and girls, ever discovered. After the Third Punic War Rome forced the Carthaginians to learn Latin, just as the Spanish imposed their language on the conquered Mexicans. Personally, what most alarms me is that there is evidence in the tophets of remains of tens of thousands of children sacrificed by fire over so many centuries. I cannot tremble more in imagining what would have been of our civilization had the Semitic Hannibal reached Rome.

Lately I’ve had contact with a child that a couple of days ago has turned six years old and who loves his mother very much. I confess that to imagine what a Carthaginian boy of the same age would have felt when his dear papa handed him over to the imposing bronze statue with a Bull’s head; to imagine what he would have felt for such treachery as he writhed with infinite pain in the fired oven, moved me to write this last chapter. Although my parents did not physically kill me (only shattered my soul), every time I come across stories about sacrificed firstborns, it’s hard not to touch my inner fiber.

In the final book of this work I will return to my autobiography, and we will see if after this type of findings humanity has the right to exist.

___________

The objective of Day of Wrath is to present to the racialist community my philosophy of The Four Words on how to eliminate all unnecessary suffering. If life allows, next time I will reproduce the final chapter. Day of Wrath will be available again through Amazon Books.