Zehn bis fünfzehn Kinder in einer Familie waren bei unseren germanischen Vorfahren gar nichts Außergewöhnliches.

Month: September 2021

No doubt all men have something in common, if only the upright posture and articulate language, which other living species do not possess. Every species is characterised by something which all its members have in common, and which the members of other species lack. The flexibility and purr of felines are traits that no other species can claim. We do not dispute that all human races have several features in common, simply because they are human. What we do dispute is that these common traits are more worthy of our attention than are the enormous differences between races (and often between human individuals of the same race), and the features that all living things, including plants, have in common.

In our eyes a Negro or a Jew, or a Levantine without a well-defined race, has neither the same duties nor the same rights as a pure Aryan. They are different; they belong to worlds which, whatever their points of contact may be on the material plane, remain alien to each other. They are different by nature—biologically Others. The acquisition of a ‘common culture’ cannot bring them together, except superficially and artificially, because ‘culture’ is nothing if it has no deep roots in nature.

Our point of view is not new. Already the Laws of Manu assigned to the Brahmin and the Soudra—and the people of each caste—different duties and rights, and very different penalties to the possible murderers of members of different castes. Caste is—and was in ancient India—linked to race. (It is called varna, which means ‘colour’, and also jat, race). Less far from us in time, and in this Europe where the contrasts between races have never been so extreme, the legislation of the Merovingian Franks, like that of the Ostrogoths of Italy, and the other Germans established in conquered countries, provided for the murder of a man of the Nordic race—of a German—penalties out of proportion to those incurred by the murderer of a Gallo-Roman or an Italian, especially if the latter was of servile condition.

Our point of view is not new. Already the Laws of Manu assigned to the Brahmin and the Soudra—and the people of each caste—different duties and rights, and very different penalties to the possible murderers of members of different castes. Caste is—and was in ancient India—linked to race. (It is called varna, which means ‘colour’, and also jat, race). Less far from us in time, and in this Europe where the contrasts between races have never been so extreme, the legislation of the Merovingian Franks, like that of the Ostrogoths of Italy, and the other Germans established in conquered countries, provided for the murder of a man of the Nordic race—of a German—penalties out of proportion to those incurred by the murderer of a Gallo-Roman or an Italian, especially if the latter was of servile condition.

No idea that is justified by healthy racism is new.

On the other hand, we do not understand this priority given to ‘man’, whoever he may be, over any subject of another living species, for the sole reason that ‘he is a man’. It is all very well for the followers of man-centred religions to believe in this priority and to take it into account in all the steps of their daily life. For them, this is the object of an article of faith, the logical consequence of a dogma. And faith cannot be discussed.

But that so many thinkers and so many people who, like them, do not belong to any church, who even fight against any so-called revealed religion, have exactly the same attitude and find the last of the human waste more worthy of concern than the healthiest and most beautiful of beasts (or plants); that they deny us the ‘right’ not only to kill without suffering, but even to sterilise defective human beings, when the life of a healthy and strong animal doesn’t count in their eyes, and that they will, without remorse, cut down a beautiful tree whose presence ‘bothers them’, is what shocks us deeply; what revolts us.

All these self-styled independent minds, all these ‘free’ thinkers, are, just as the believers of the man-centred religions and so-called human ‘dignity’, slaves of the prejudices that the West and a large part of the East. They have inherited it from Judaism. If they have rejected the dogmas and mythology of anthropocentric religions, they have retained their values in their entirety. This is as true of the eighteenth-century Deists as it is of our atheistic Communists. [Editor’s Note: The POV of this site about ‘neochristianity’ in a few words! Savitri continues:]

Although most anti-Communist Christians indignantly reject the idea, there is a profound parallelism between Christianity and Marxism. Both are originally Jewish products. Both have received the imprint of a more or less decadent Aryan thought: that of the subtle Hellenistic philosophy, overloaded with allegories and ready to accept the most unexpected syncretisms, in the case of the former—and of that ideology not of the true scientific spirit, which guards against error, but of what I will call ‘scientism’: the propensity to replace faith in traditional ideas by faith that is presented in the name of ‘Science’, in the case of the latter.

And above all, both are centred on the same values: on the cult of man, as the only being created ‘in the image and likeness’ of the god of the Jews, or simply as a being of the same species as the Marxist who glorifies him. The practical result of anthropo-centrism is the same, whatever its source.

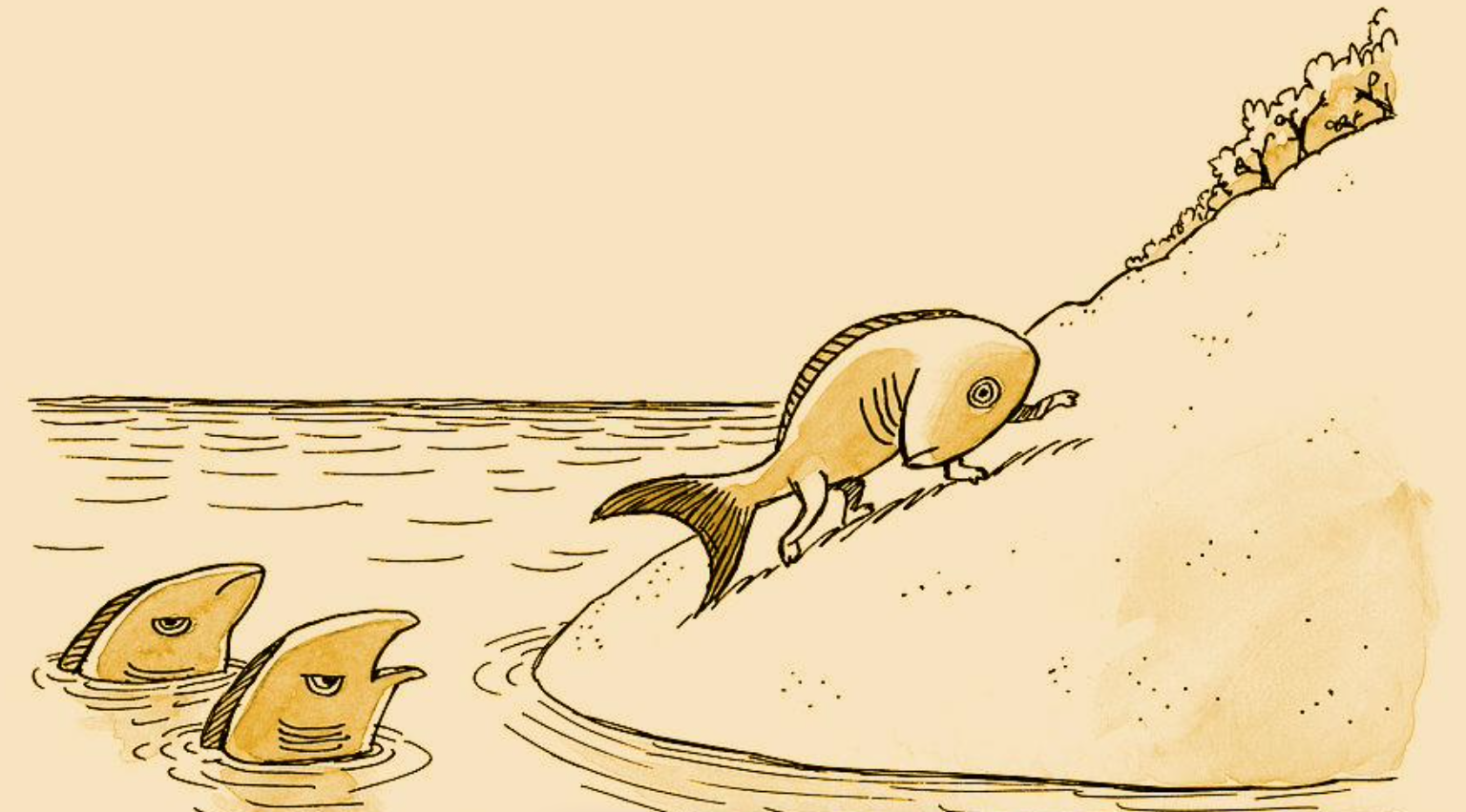

‘The white nationalists of today’, said Mauricio this morning, ‘are like Kantian fish, trying to make sense out of the progressively muddying Christian water, when instead they should become Nietzschean amphibians and get out of the drying lake, by reversing all values, and into the Aryan river of life, where might makes right’.

‘The white nationalists of today’, said Mauricio this morning, ‘are like Kantian fish, trying to make sense out of the progressively muddying Christian water, when instead they should become Nietzschean amphibians and get out of the drying lake, by reversing all values, and into the Aryan river of life, where might makes right’.

Anon, presumably an American, is a good example. At midnight he said on this site: ‘I can’t prove it, but I believe it quite likely that Eisenhower was a jew’. Why? Because he hated Germans.

I find this typical mono-causality among American white nationalists particularly irritating. It’s like trying to discuss with fundamentalist Americans who reduce everything to accepting Jesus as your personal Lord and Saviour. White nationalists have eaten so many Jews for breakfast that vital news, like Biden’s confession that he wanted to flood masses of non-whites into the US for the specific purpose that whites become an ethnic minority (see Tucker Carlson’s very recent words: here) are considered a by-product… of the JQ!

Even the fact that many white Americans feel like Biden (their new religion is to exterminate whites), as recently discussed by Kevin MacDonald in his webzine, doesn’t motivate them to become amphibians.

But Kant—so independent and so strong in the field of criticism of knowledge—had a moral teacher, apart from the Christian teaching of his family: Jean-Jacques Rousseau, whose influence was still being felt throughout Europe at that time.

But Kant—so independent and so strong in the field of criticism of knowledge—had a moral teacher, apart from the Christian teaching of his family: Jean-Jacques Rousseau, whose influence was still being felt throughout Europe at that time.

I can hardly imagine two men more different from each other than Rousseau, the perpetual wanderer, whose life was somewhat disordered, to say the least, and the meticulous Herr Professor Immanuel Kant, whose days and years were all alike, passing according to a rigorous schedule where there was not the slightest room for the unexpected or the whimsical.

Jean-Jacques Rousseau never misses an opportunity in his works to exalt ‘reason’ as well as ‘virtue’. But he seems to have had no rules of conduct other than his fantasy, or his impulses, with the result that the story of his life gives an impression of inconsistency, not to say imbalance. A poet rather than a thinker, he dreamed his existence; he did not live it—and especially not according to fixed principles.

The love he professed, whenever he could—on paper—for children, didn’t prevent him from putting his five children, one after the other, in the Assistance Publique on the pretext that the woman who had given them to him, Thérèse Levasseur, would have been incapable of bringing them up in the spirit he would have liked. And this abandonment, repeated five times, didn’t prevent him from writing a book about the education of children, and—what is worse—didn’t prevent the public from taking him seriously! He was taken seriously because, while believing himself to be highly original, he reflected the trends of his time, above all the revolt of the individual against Tradition in the name of ‘reason’.

It is not surprising that the enemy spirits of the visible traditional authorities, that is to say of kings and the clergy, should have chosen him enthusiastically as their guide, and placed the French Revolution, which they were organising, under his sign. It seems, at first sight, less natural that Kant should have been so strongly influenced by him.

But Kant was a man of his time, a time when Rousseau had seduced the European intelligentsia, partly by his poetic prose and paradoxes, partly by certain clichés, which come up everywhere in his work: the words ‘reason’, ‘conscience’ and ‘virtue’. It was these clichés that gave Kant’s limited imagination the opportunity for all the flight of which he was capable, and that gave the German philosopher the form of his morality.

The content of this morality—as indeed that of Rousseau himself and all the ‘philosophers’ of the 18th century and, before them, that of Descartes, the true spiritual father of the French Revolution—is drawn from the old foundation of Christian ethics, centred on the dogma of the ‘dignity’ of man, the only being created ‘in the image of God’, out of respect for this privileged being [red by Editor].

In other words, with meticulous honesty and quite Prussian application and perseverance, Kant tried to establish as a system the common humanitarian morality in Europe, because of Christian morality, which Rousseau had glorified in sentimental effusions: that morality which Nietzsche was one day to have the honour of demolishing with his pen, and which we were later destined to negate, by action.

______ 卐 ______

Editor’s note: By ‘later’ she probably meant during the Third Reich. Unlike the Nazis, American white nationalists continue to subscribe to Christian ethics, including atheists. Incidentally, why ‘Rousseau’s babble was utter nonsense’, as Revilo Oliver wrote, can be seen: here.

Does my audience begin to tell the difference between a common white nationalist and a priestess (or priest) of the 14 words?

Kant and friends on table

Is there such a thing as objectivity in the field of values? [Editor’s note: formally known as ‘axiology’]. To this question I answer yes. There is something independent of the ‘taste’ of each art critic, which makes a masterpiece of painting, sculpture or poetry a masterpiece for all time. Behind every perfect creation—and not only in the field of art proper—there are secret correspondences, a whole network of ‘proportions’ which themselves ‘recall’ unknown but prescient cosmic equivalences. It is these elements that link the work to the eternal—in other words, that give it its objective value.

On the other hand, there is no universal scale of preferences. Even if one could penetrate the mystery of the structure of eternal creations, which are human only in name because the author has effaced himself before the Force (the ancients would have said: ‘the God’), who for a moment possessed him, and acted through it and by it—if one could, say, explain in clear sentences like those of mathematicians, why such creations are eternal, one could never force everyone to prefer the eternal to the temporary; to find a work which reflects something of the harmony of the cosmos, more pleasant, more satisfying than another, which reflects anything.

There is good and bad taste. And there are moral consciences that are more or less similar to those of a man with an objective scale of values. But there is no more universal consciousness than there is universal taste. There is no such thing, and there can be no such thing, for the simple reason that the aspirations of men are different, once they have passed the level of the most elementary needs. (And even these needs are more or less pressing, depending on the individual. Some people find life bearable, even beautiful, without comforts, pleasures or affections, the lack of which would make other people frankly unhappy.)

Different aspirations mean different preferences. Different preferences mean different reactions to the same events, different decisions in the face of the same dilemmas, and therefore different ways of organising lives that might otherwise have been similar. Never forget the diversity of human beings, even within the same race, let alone from one race to another. How can people who are so different from each other have ‘the same rights and the same duties’?

There is no more universal duty than there is universal consciousness. Or, if we absolutely want to find a formula that is true for all, we must say that the duty of every man—indeed, of every living being—is to be to the end, in his visible or secret manifestations, what he is in his deepest nature; to never betray himself.

But deep natures differ. Hence, despite everything, the diversity of duties, as well as of rights, and the inevitable conflict, on the level of facts, between those who have opposite duties. The Bhagawad-Gîta says: ‘Focus on fulfilling your duty (svadharma). The duty of another involves (for you) many dangers’.

And what, in practice, will decide the outcome of the conflict between people with opposing duties? Force. I can only think of it. If I don’t have it, I have to put up with the presence in the world of institutions that I consider criminal, given my own scale of values. I can hate them. I cannot remove them with the stroke of a pen, as I would if I had the power. And even those who have power can not—insofar as they need the collaboration of some men, if not of a majority, precisely to maintain the position they have conquered. But I shall speak to you later about force, the condition of any visible and sudden change, that is to say of any victorious revolution, on the material plane.

I will first tell you a few words about the fathers of ‘universal consciousness’ and the idea that derives from it: the idea of a ‘duty’ that would be the same for all. I will recall the names of only a few of them who, in fields other than morality, are distinguished by some preeminence: by the firmness of their thought or the beauty of their prose.

First, there is Immanuel Kant, to whom we must be infinitely grateful for having drawn the line between scientific knowledge and metaphysical speculation; between what we know, or what we can know, and what we can only speak about arbitrarily, knowing nothing about it, or not at all, the direct vision we have of it is incommunicable. The whole part of Kant’s work that deals with the subordination of thought to the categories of space and time, and with the impossibility of going beyond the sphere of ‘phenomena’ with our conceptual intelligence, is of exemplary solidity.

______ 卐 ______

Editor’s Note: Infinitely grateful? Exemplary solidity? Lol! As we saw in my previous post, ‘On Shelob’s lair’, on this issue Savitri errs. But she continues:

______ 卐 ______

The recipes given by the thinker to help every man discover ‘the duty’, which he believes to be the same for all, are less worthy of credence, precisely because they do not fall within the scope of what, according to Kant’s deductions, makes up the essence of the scientific mind.

We are here in the realm of values—not of ‘facts’, not of ‘phenomena’. The only ‘fact’ that could be noted in this connection is the diversity of value scales. And Kant takes no account of this. He believes he bases his notion of ‘duty’ on that of ‘reason’. And since reason is ‘universal’, the laws of discursive thought being so—two and two make four for the last of the Negroes, as well as for one of us—it seems that duty must be too.

Kant does not realise, as his values seem indisputable to him, that it is not ‘reason’ at all, but his austere Christian upbringing—pietistic, to be more precise—which dictated them to him; that he owes them, not to his ability to draw conclusions from given premises—an ability which he shares with all sane men, and perhaps with the higher animals—but to his spontaneous submission to the influence of the moral environment in which he was brought up. He forgets—and how many have forgotten before and after him, and still do!—that reason is powerless to set ends; to establish orders of preference; that, in the domain of values, its role is limited to highlighting the logical—or practical—link between a given end and the means that lead to its realisation.

Reason can tell an individual what his ‘duty’ will be in a specific circumstance if, for example, he loves all men, or better still, all living beings. Reason cannot force him to love them, if he doesn’t feel attracted to them. It can suggest to him what to do, or not do, if he wants to contribute to ‘world peace’. It cannot force him to want peace. And if he does not want it, if he finds it demoralising or simply boring, it will suggest to him, with equal logic, an entirely different course of action—just as it will direct the intelligent misanthrope to an entirely different course of action from that which it would command the philanthropist. It will always command each of those who think, the action that corresponds to the promotion of what he really loves, and deeply wants. How could it inspire duties, identical in content, to individuals who love different, even incompatible ideals, and who each want the revolution that their ideal implies? Or to individuals who love only people, and to others who love only ideas?

‘Always act’, says Kant, ‘as if the principle of your action could be set up as a universal law’.

How can this ‘rule’ be applied both to the conduct of one who, loving only his family and friends, far from sacrificing them to any idea whatsoever, will feel that it is ‘his duty’ to protect them at all costs, and that of the militant who, loving only a cause which goes beyond him, considers that it would be ‘his duty’, if necessary, to sacrifice him and his recent collaborators (as soon as he feels them weakening in terms of orthodoxy and becoming dangerous), and a fortiori his family, alien to the holy ideology, as soon as he sees one of its members, whoever he may be, making a pact with the hostile forces?

______ 卐 ______

Editor’s note: Remember Savitri’s words in my Friday’s post: ‘During the war, my mother—although 75 years old in 1940, 80 in 1945—joined the resistance movement in France. I did not know it naturally. There was no communication between Calcutta and Europe. She told me in 1946, when I visited her, and said also that if I had been present in France in 1944 and had actively worked against the resistance (as I then surely would have), she would have handed me over to the resistance’.

______ 卐 ______

And what about the rule: ‘Always act in such a way that you take the human person as an end, never as a means’? In other words: ‘Never use a man’. And why not?—especially if, by using him, I am working in the interest of a Cause that is much greater than him, for example, the cause of Life, or the human elite (the elite of every living species) or simply that of a particular people, if this one has a more than human historical mission?

Man unscrupulously exploits the animal and the tree in favour of what he believes to be his own interest. And Kant apparently finds no fault with this. Why should we not exploit man—the ‘human person’ whose so-called ‘value’ we have been hearing about more than ever for the past quarter-century—in the interest of Life itself? What prevents us from doing so, if we do not have—like Immanuel Kant and so many others; like most people born and raised in a Christian (or Islamic, or Jewish, or simply ‘secular’) civilisation—a scale of values centred around the sacrosanct two-legged mammal?

Of myself, if I love ‘all men’, I won’t use any of them; I won’t take any of them ‘as a means’, for an end which is not him. You don’t exploit what you really love. This is a psychological law.

But no ‘reason’ can force me to ‘love all men’—any more than it can force most men to love all animals. Kant’s ‘reason’ ordered him not to exploit any human being, not because this is a universal commandment, but because he loved all men, like the good Christian he was. I, who do not love them all, do not feel that this ‘duty’ concerns me. It is not my duty. I refuse to submit to it. And if a man who finds the exploitation of animals and trees—and what exploitation!—quite natural, dares to come and preach me about ‘respect for the human person’, I would brutally send him to mind his own business.

______ 卐 ______

Editor’s Note: This is more than fundamental. If there is something that my work From Jesus to Hitler teaches, it is that we must stop loving the vast majority of humans to save the nymphs of the sidebar and the animals under the human yoke.

On Shelob’s lair

Or: Kant’s trap

In the modern world, Immanuel Kant has been the poet’s greatest enemy, the enemy of clear, concise and transparent prose (my style).

Kant initiated the dark movement of German idealism, from which perhaps only the German nationalist pronouncements of Fichte are salvageable. While German music and literature were luminous (think of Beethoven and Goethe), German philosophy was tremendously obscurantist: and a thin tail of that cobweb even reached its way about how Mein Kampf was elaborated.

David Irving is correct that he never read Mein Kampf because, as an exact historian of the Third Reich, he didn’t want a text dipped into feather pens other than Hitler’s to contaminate his true biography (which is why Irving recommends reading daily each of the after-dinner talks of Uncle Adolf: these are uncontaminated). Mein Kamp is a PR book written for a people who, influenced by their philosophers’ style, had already betrayed the lyrical way of writing. For the same reason I don’t recommend The Gulag Archipelago, but the excellent abbreviation made by an Englishman, with the permission of the Russian author, that reads like an entertaining novel. I sincerely believe that an abridged edition of Mein Kampf should be tried, trying to keep only the passages that Hitler dictated.

But even in Hitler’s Table Talk I see a couple of disagreements with our Führer. One of them was a short sentence in which he expressed himself about the genius of Kant. As John Martínez said more than eight years ago on this site:

In another post you mentioned the fact that not a single one of the supposedly greatest philosophers ever said something about the importance of race to the establishment of a great civilisation like ours. That is to say, these guys have devoted millions of man-hours [Shelob’s trap] to discussing every single subject under the sun—except for what is perhaps the most important of them all from the point of view of our civilisation: the fact that it is a White civilisation and that these discussions are not taking place in Africa, Asia or what have you.

As Nietzsche scoffed at using an English word, Kant is ‘Cant’: his prose was empty and insincere, and he shouldn’t have hypnotised the Germans. The only proponent of the German Enlightenment worth rescuing was Hermann Samuel Reimarus, who initiated the discipline of analysing the New Testament that recently culminated in Richard Carrier’s book. The rest was hot air.

Matthew Stewart

In my home library I have many books from the publisher Prometheus Books, which taught me to distrust the pseudosciences of the paranormal and even early Christianity (for example, the book that collects the surviving fragments of the 4th-century book that the philosopher Porphyry wrote against Christians, was published by Prometheus). Stewart’s first book was also published by Prometheus, The Truth About Everything. He believes that we have lost sight of what philosophy was in its original conception, and wrote that iconoclastic pamphlet to poke fun at academic philosophy.

In the chapter on Kant, Stewart asserts that this German philosopher was no Copernicus. On the contrary: his ‘metaphysics’ is one of the possible manifestations of a philosophical trend. Regardless of Kant’s influence, because of the apotheosis that was applied to him after his death, his name, says Stewart, is only a point of convergence of a plethora of beliefs based on the mistakes of Descartes.

Since, like Descartes, in those times the aim of the philosophers whose parents were Christians had been the reconciliation between science and religion, Kant divided the world into two absolutely disconnected worlds. Using my language, the celebrated philosopher of the kingdom of Prussia was just another guy who didn’t know how to shake off his parental introjects. The Kantian dream of ‘perpetual peace’ reminds me of the pictures of the lion laying with the lamb of the Jehovah’s Witnesses who ring the doorbell of my house.

I said that Prometheus Books warned me against pseudosciences. In one of the Martin Gardner books that I own, this hilarious writer informs us that crank scientists love to develop new vocabularies and mystifying language (imagine the hundreds of neologisms that L. Ron Hubbard created for Scientology).

A feature of Kant’s work is its vast technical vocabulary and abominable prose. Stewart tells us that if one translates Kant’s newspeak into oldspeak (the same is possible with Hubbard’s neologisms) it is possible to begin to see behind the smokescreen and mirrors of the three Kantian ‘critiques’.

For example, a priori / a posteriori are Latin words that simply mean ‘before’ and ‘after’ in a logical rather than temporal sense. But those who are not alert to the crank sciences will believe that there is something very profound when Kant speaks to us, say, about the ‘transcendental unity of apperception’, or of the ‘transcendental ego’ (the latter reminds me of Hubbard’s ‘operative thetan’!). Even with the word ‘pure’ in his Critique of Pure Reason, Kant means ‘uncontaminated by experience’.

According to Stewart, this repertoire of concepts seems to be sophistry and illusion, adding that Kant succumbs to the medieval error of turning a tedious logic into a radical ontological falsehood (How many angels can fit on the head of a pin?). Stewart also claims that Kant confines the science of the world to projections and shadows, mere appearances, and all this to save religion. The Categorical Imperative is the Kantian machine for the Moral Law (read: the education that little Immanuel received as a child in a religiously abusive home) based on ‘reason’ (and, to boot, we must take into account the cryptic definition of ‘reason’ by Kant).

Beyond the very dense Kantian jargon, this guy surreptitiously inserts the substance into the bosom of an otherwise purely formal theory. That’s why, Stewart affirms, the Critique of Practical Reason is a betrayal, and that this is the key we need to decipher Kantian ethics: the result of the standards that Kant received as a child in the bosom of a pietistic Christian family. (Pietistic Lutheranism is a movement within Lutheranism that combines its emphasis on biblical doctrine with an emphasis on individual piety and living a vigorous Christian life.)

Stewart’s criticism is not original. Almost all of his arguments were defended in writing by living characters as a result of the publication of the first Kantian critique. The problem is that modern ‘philosophers’ share the apotheosis of Kant, and generally believe in the professional respectability of that crank thinker. The Eastern gurus (think of the Zen monks) hypnotise the faithful by saying things that are extremely unpleasant for commonsensical ears, but presented as profound metaphysical truths. Kant’s promise that he was able to reverse the basis of all knowledge, from ‘object’ to ‘subject’, is just this kind of psyop to dupe the unwary.

In sum, Stewart tells us, Kant’s obscurity is the critical factor in allaying the concerns of those who have brought Kant to the universities. His obtuse distinctions exude an air of professionalism and his twisted arguments give the impression of depth. The resulting inconsistencies supply grain for the controversial windmills of academic philosophy.

All that Stewart says invalidates not only bestsellers on philosophy like the bestselling story that Will Durant wrote, but what they want to teach us in the academy under the pretentious name of ‘philosophy’, supposedly love of wisdom. Stewart concludes by telling us that both the rationalists and the empiricists of the 17th century tried to take philosophy out of the monasteries, turning it into the fiefdom of the amateurs. Kant collected his ideas at the service of a return to the monastic age. After him, philosophy was to be safe from rebellious amateurs and returned to its peaceful seminaries and universities. Of course, the new theologians were no longer debating the sex of angels. They are masturbating themselves, intellectually, with ‘the facts of conscience’. Aristotle ceased to be the object of scholastic comments to be relieved by Kant.

Nietzsche wrote: ‘Kant’s success is just a theologian success: Kant, like Luther, like Leibniz, was one more drag on an already precarious German sense of integrity… Kant became an idiot. — And such a man was the contemporary of Goethe! This disaster of a spider (*) passed for the German philosopher!’

___________

(*) For Francis Bacon (1561-1626) the metaphysicians were like spiders that constructed their webs with a substance segregated from their insides, resulting in that their conclusions kept little if any connection to empirical reality. Kant has been the biggest spider of all, Tolkien’s Shelob! The number of philosopher’s apprentices who have fallen into his cobwebs trying to decipher them, in a vain search for wisdom, is legion.

The more rigorous a reasoning is, impeccable from the purely logical point of view, the more its conclusion is false if the basic judgement from which it starts—the one expressed by its major premise, in the case of a simple syllogism—is itself false. This is clear. If I declare that ‘All men are saints’ and then I notice that the Marquis de Sade and all known and unknown sexual perverts, and all animal or child torturers, were or are men, I am forced to conclude that all these people were or are saints: an assertion whose absurdity is obvious.

The more rigorous a reasoning is, impeccable from the purely logical point of view, the more its conclusion is false if the basic judgement from which it starts—the one expressed by its major premise, in the case of a simple syllogism—is itself false. This is clear. If I declare that ‘All men are saints’ and then I notice that the Marquis de Sade and all known and unknown sexual perverts, and all animal or child torturers, were or are men, I am forced to conclude that all these people were or are saints: an assertion whose absurdity is obvious.

Perfect logic only leads to a true judgement if it is applied based on major premises that are themselves true. The adjectives by which we characterise such rigour in the sequence of judgements depend on one’s attitude towards the judgement from which it starts. If one accepts it, one speaks of an irreproachable or admirable logic. If one rejects it vehemently, as Mr Grassot rejected the basic propositions of Aryan racism, in other words Hitlerism, one will speak of ‘appalling logic’. This does not matter, since judgements remain true or false, regardless of the reception, always subjective, that is given to them.

Now, what is a true judgment?

Any judgement expresses a relationship between two states of fact, between two possibilities, or between a state of affairs (and all psychological states fall under this category) and a possibility. If I say, for example, ‘The weather is fine’, I am relating a whole set of sensations that I am currently experiencing to the presence of the sun in the visible sky. If I say: ‘The sum of angles of a triangle equals the straight angle’ I am stating that, if a polygon has the characteristics which, mathematically, define the triangle, the sum of its angles will be, and can only be, equal to the straight angle; that there is a necessary relationship between the very definition of ‘triangle’, and the property to which I have alluded. If I say: ‘It is better to lose your life than to fail in honour’, I make a connection—no less necessary in principle—between my psychology and a possible situation in which I would have to choose either to live dishonoured, or to die saving honour.

The judgement is true if the relationship it expresses exists; otherwise, it is false. This is clear in the case of judgements—called ‘categorical’—which posit a relationship between two facts. If I say in broad daylight that ‘it is dark’, it is quite certain that there is no longer any connection between what my senses experience and what I say; the judgment is therefore false. If I say: ‘The sum of the angles of a triangle is equal to five angles’ I am saying an absurdity, because the connection I’m making here between the definition of the triangle and a property I attribute to it does not exist; the assertion contradicts the judgement that defines the triangle. (Even in non-Euclidean space with positive curvature, where the sum of the angles of a triangle ‘exceeds’ two right angles, that sum does not reach ‘five angles’.)

In the case of categorical judgements, which express a relation between two facts, as in the case of those perfect hypothetical judgements which are the theorems of mathematics, the ‘truth’ or ‘falsity’ are evident. No one will certainly accept what I am saying if I declare in broad daylight that ‘it is night’ for every healthy eye sensitive to light. As for mathematical theorems, they can all be proved, provided that one accepts, in the case of geometrical theorems, the postulates that define the particular space they concern.

The only judgements people argue about, until they go to war because of them, are value judgements: those which presuppose, in whoever emits them, a hierarchy of preferences. It is, in fact, always in the name of such hierarchy that we grasp a relation between a fact (or a state of mind) and a ‘possibility’ (future, or else conceived retrospectively, as what might have been). Facts can give rise to heated discussions, no doubt, but devoid of passion, and especially hatred.

______ 卐 ______

Editor’s Note: No longer in our time! when elemental facts—like saying that boys are boys and girls are girls; or that there are no grandmasters in chess tournaments who are black—can lead to such hatred that we may lose our jobs. To call ‘a spade a spade’ is now considered racist.

Some bien pensant censors are even suggesting that the expression ‘To call a spade a spade’ should be retired from modern usage! A newspeaker said: ‘Rather than taking the chance of unintentionally offending someone or of being misunderstood, it is best to relinquish the old innocuous proverbial expression all together’ (see: here).

______ 卐 ______

One does not really quarrel with one’s adversaries and, if one has the power to do so, one only cracks down on them, unless one considers the ‘facts’, which are the subject of the discussion, to be directly or indirectly linked to values that we love.

The Church has been hostile to those who maintained that our Earth is round and that it is not the centre of the solar system, insofar as the belief in these facts—in case they were proven and therefore universally accepted—negate not only of the letter of the Scriptures but, above all, Christian anthropocentrism. The biological facts which form the basis of all intelligent racism are denied by organisations such as UNESCO, which pride themselves on ‘culture’. They do it only because these organisations see, in a widespread acceptance of this premise, the threat of a resurgence of Aryan racism, which they detest.

Eisenhower

A concerned reader said today:

In regards to the Christian question (CQ), it is about time that every Aryan soul must seriously ponder and contemplate it. Christianity had always been a ticking time bomb for all Aryans. It finally exploded with devastating force in 1945, when National Socialist Germany, the last bastion of Aryandom in the 20th century, was defeated by Christian ethics. It is a great defeat not just for Germany, but for the entire Aryankind. National Socialist Germany was the last conscious awakening of the greater Aryan collective and the Aryan’s last chance to conquer the stars and be the rightful dominant sentient species in the universe.

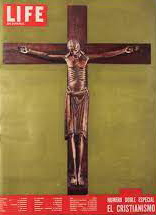

These days I have been leafing through the old collection of Life magazines in Spanish that my father left in the family library. The idea was to compare the American zeitgeist of the 1950s and 60s with that of today.

I had been left with an idealised image about those magazines that I leafed through as a child, as in those days almost only white people were shown off in the images. But these days when I go back to leafing through them, through their handsome advertisements I see that those magazines show that Americans were already ruthlessly worshipping Mammon. Actually, they seemed Calvinists quoting Calvin: that whoever can get rich and does not do so, sins. The worst thing was what I came across at midnight in the double issue of January 30, 1956, on Christianity.

Ironically, as the magazines are in Spanish, I cannot quote verbatim the content, as that would mean that I would retranslate some passages back into English: a translation that would differ from the original English text. But I can say that, in the editorial for this issue, we are informed that President Eisenhower was a very devout Presbyterian, and that he spoke on religious matters with great fervour and conviction. In fact, in more than fifty speeches that Eisenhower delivered since he perpetrated the Hellstorm Holocaust, he emphasised the great significance that religion had for all of humanity.

Ironically, as the magazines are in Spanish, I cannot quote verbatim the content, as that would mean that I would retranslate some passages back into English: a translation that would differ from the original English text. But I can say that, in the editorial for this issue, we are informed that President Eisenhower was a very devout Presbyterian, and that he spoke on religious matters with great fervour and conviction. In fact, in more than fifty speeches that Eisenhower delivered since he perpetrated the Hellstorm Holocaust, he emphasised the great significance that religion had for all of humanity.

The editorial quotes a text by the president, who confesses that he was born into a very religious family, and that his parents taught him that the principle of wisdom starts with the fear of god (the god of the Jews). Eisenhower spoke of the ‘ética cristiana’—sic, Christian ethics—, and that his ancestors had proven that a people who believed in god (the god of the Jews) had enough strength to liberate other peoples and challenge the tyrants of the 20th century.

All of this, of course, reminds me of what Tom Sunic wrote in his book Homo Americanus: that the United States is a country based on theology, and that the Hellstorm Holocaust was a biblically inspired sin, according to his words.

Interestingly, in the editorial the editor openly says that the United States is the largest Christian nation on earth, and on the next page he again quotes Eisenhower. The president confessed that during World War II he had discovered his unshakable belief in the Bible, and that religion inspired him to make the necessary decisions (I suppose he was referring to the death camps he created for defenceless Germans).

Page 7 of that issue of Life shows a close-up of Eisenhower praying with great devotion on the historic Gettysburg battlefield.

WDH – pdf 400

Das echte und unverbildete deutsche Mädchen sehnt sich nach dem Kinde und dem Glück der Mutter… Auch das unehelich geborene Kid ist ein wertvolles Glied der Volksgemeinschaft, sofern es von erbgesunden, nordisch bestimmen Eltern gezeugt wurde.