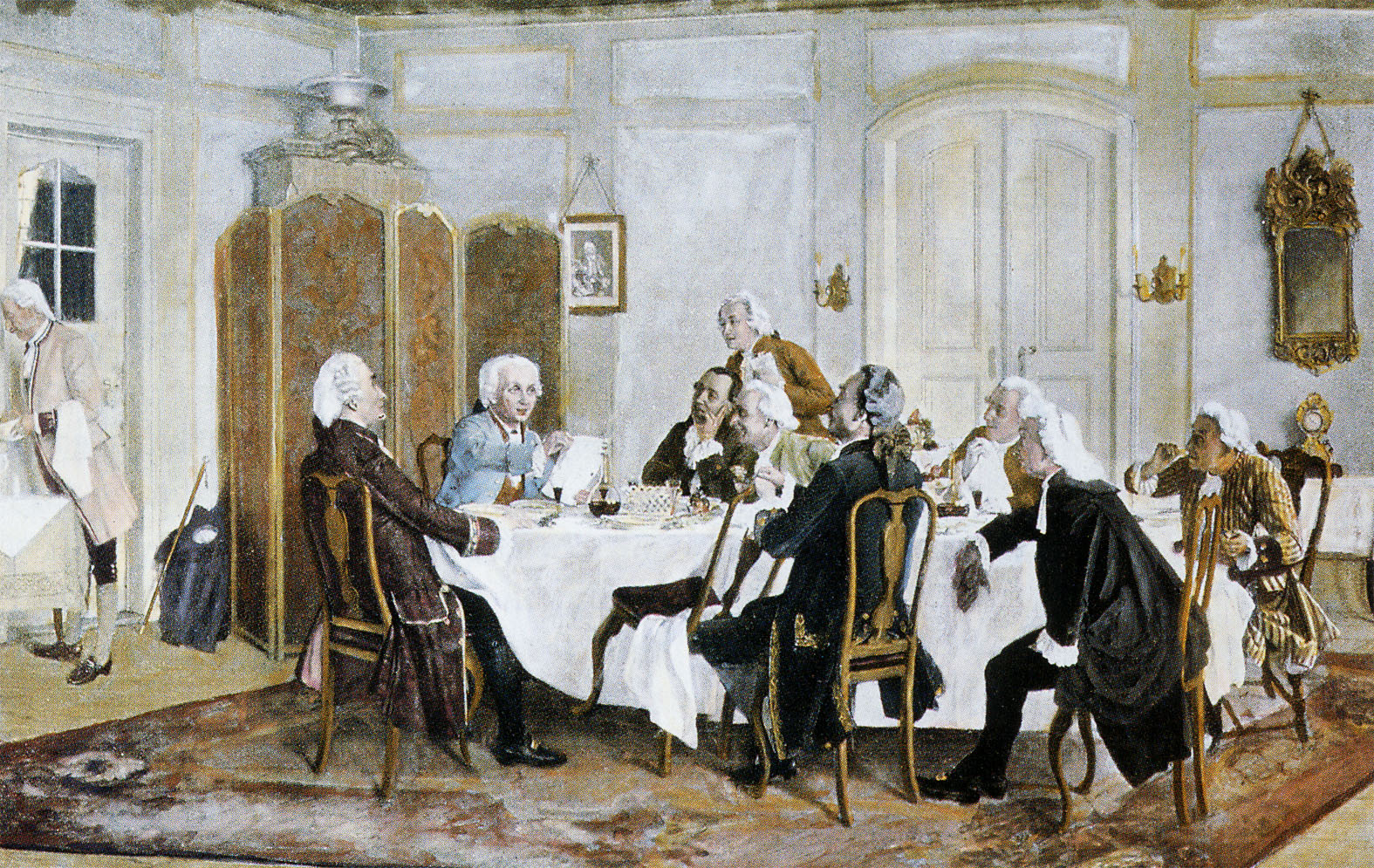

Kant and friends on table

Is there such a thing as objectivity in the field of values? [Editor’s note: formally known as ‘axiology’]. To this question I answer yes. There is something independent of the ‘taste’ of each art critic, which makes a masterpiece of painting, sculpture or poetry a masterpiece for all time. Behind every perfect creation—and not only in the field of art proper—there are secret correspondences, a whole network of ‘proportions’ which themselves ‘recall’ unknown but prescient cosmic equivalences. It is these elements that link the work to the eternal—in other words, that give it its objective value.

On the other hand, there is no universal scale of preferences. Even if one could penetrate the mystery of the structure of eternal creations, which are human only in name because the author has effaced himself before the Force (the ancients would have said: ‘the God’), who for a moment possessed him, and acted through it and by it—if one could, say, explain in clear sentences like those of mathematicians, why such creations are eternal, one could never force everyone to prefer the eternal to the temporary; to find a work which reflects something of the harmony of the cosmos, more pleasant, more satisfying than another, which reflects anything.

There is good and bad taste. And there are moral consciences that are more or less similar to those of a man with an objective scale of values. But there is no more universal consciousness than there is universal taste. There is no such thing, and there can be no such thing, for the simple reason that the aspirations of men are different, once they have passed the level of the most elementary needs. (And even these needs are more or less pressing, depending on the individual. Some people find life bearable, even beautiful, without comforts, pleasures or affections, the lack of which would make other people frankly unhappy.)

Different aspirations mean different preferences. Different preferences mean different reactions to the same events, different decisions in the face of the same dilemmas, and therefore different ways of organising lives that might otherwise have been similar. Never forget the diversity of human beings, even within the same race, let alone from one race to another. How can people who are so different from each other have ‘the same rights and the same duties’?

There is no more universal duty than there is universal consciousness. Or, if we absolutely want to find a formula that is true for all, we must say that the duty of every man—indeed, of every living being—is to be to the end, in his visible or secret manifestations, what he is in his deepest nature; to never betray himself.

But deep natures differ. Hence, despite everything, the diversity of duties, as well as of rights, and the inevitable conflict, on the level of facts, between those who have opposite duties. The Bhagawad-Gîta says: ‘Focus on fulfilling your duty (svadharma). The duty of another involves (for you) many dangers’.

And what, in practice, will decide the outcome of the conflict between people with opposing duties? Force. I can only think of it. If I don’t have it, I have to put up with the presence in the world of institutions that I consider criminal, given my own scale of values. I can hate them. I cannot remove them with the stroke of a pen, as I would if I had the power. And even those who have power can not—insofar as they need the collaboration of some men, if not of a majority, precisely to maintain the position they have conquered. But I shall speak to you later about force, the condition of any visible and sudden change, that is to say of any victorious revolution, on the material plane.

I will first tell you a few words about the fathers of ‘universal consciousness’ and the idea that derives from it: the idea of a ‘duty’ that would be the same for all. I will recall the names of only a few of them who, in fields other than morality, are distinguished by some preeminence: by the firmness of their thought or the beauty of their prose.

First, there is Immanuel Kant, to whom we must be infinitely grateful for having drawn the line between scientific knowledge and metaphysical speculation; between what we know, or what we can know, and what we can only speak about arbitrarily, knowing nothing about it, or not at all, the direct vision we have of it is incommunicable. The whole part of Kant’s work that deals with the subordination of thought to the categories of space and time, and with the impossibility of going beyond the sphere of ‘phenomena’ with our conceptual intelligence, is of exemplary solidity.

______ 卐 ______

Editor’s Note: Infinitely grateful? Exemplary solidity? Lol! As we saw in my previous post, ‘On Shelob’s lair’, on this issue Savitri errs. But she continues:

______ 卐 ______

The recipes given by the thinker to help every man discover ‘the duty’, which he believes to be the same for all, are less worthy of credence, precisely because they do not fall within the scope of what, according to Kant’s deductions, makes up the essence of the scientific mind.

We are here in the realm of values—not of ‘facts’, not of ‘phenomena’. The only ‘fact’ that could be noted in this connection is the diversity of value scales. And Kant takes no account of this. He believes he bases his notion of ‘duty’ on that of ‘reason’. And since reason is ‘universal’, the laws of discursive thought being so—two and two make four for the last of the Negroes, as well as for one of us—it seems that duty must be too.

Kant does not realise, as his values seem indisputable to him, that it is not ‘reason’ at all, but his austere Christian upbringing—pietistic, to be more precise—which dictated them to him; that he owes them, not to his ability to draw conclusions from given premises—an ability which he shares with all sane men, and perhaps with the higher animals—but to his spontaneous submission to the influence of the moral environment in which he was brought up. He forgets—and how many have forgotten before and after him, and still do!—that reason is powerless to set ends; to establish orders of preference; that, in the domain of values, its role is limited to highlighting the logical—or practical—link between a given end and the means that lead to its realisation.

Reason can tell an individual what his ‘duty’ will be in a specific circumstance if, for example, he loves all men, or better still, all living beings. Reason cannot force him to love them, if he doesn’t feel attracted to them. It can suggest to him what to do, or not do, if he wants to contribute to ‘world peace’. It cannot force him to want peace. And if he does not want it, if he finds it demoralising or simply boring, it will suggest to him, with equal logic, an entirely different course of action—just as it will direct the intelligent misanthrope to an entirely different course of action from that which it would command the philanthropist. It will always command each of those who think, the action that corresponds to the promotion of what he really loves, and deeply wants. How could it inspire duties, identical in content, to individuals who love different, even incompatible ideals, and who each want the revolution that their ideal implies? Or to individuals who love only people, and to others who love only ideas?

‘Always act’, says Kant, ‘as if the principle of your action could be set up as a universal law’.

How can this ‘rule’ be applied both to the conduct of one who, loving only his family and friends, far from sacrificing them to any idea whatsoever, will feel that it is ‘his duty’ to protect them at all costs, and that of the militant who, loving only a cause which goes beyond him, considers that it would be ‘his duty’, if necessary, to sacrifice him and his recent collaborators (as soon as he feels them weakening in terms of orthodoxy and becoming dangerous), and a fortiori his family, alien to the holy ideology, as soon as he sees one of its members, whoever he may be, making a pact with the hostile forces?

______ 卐 ______

Editor’s note: Remember Savitri’s words in my Friday’s post: ‘During the war, my mother—although 75 years old in 1940, 80 in 1945—joined the resistance movement in France. I did not know it naturally. There was no communication between Calcutta and Europe. She told me in 1946, when I visited her, and said also that if I had been present in France in 1944 and had actively worked against the resistance (as I then surely would have), she would have handed me over to the resistance’.

______ 卐 ______

And what about the rule: ‘Always act in such a way that you take the human person as an end, never as a means’? In other words: ‘Never use a man’. And why not?—especially if, by using him, I am working in the interest of a Cause that is much greater than him, for example, the cause of Life, or the human elite (the elite of every living species) or simply that of a particular people, if this one has a more than human historical mission?

Man unscrupulously exploits the animal and the tree in favour of what he believes to be his own interest. And Kant apparently finds no fault with this. Why should we not exploit man—the ‘human person’ whose so-called ‘value’ we have been hearing about more than ever for the past quarter-century—in the interest of Life itself? What prevents us from doing so, if we do not have—like Immanuel Kant and so many others; like most people born and raised in a Christian (or Islamic, or Jewish, or simply ‘secular’) civilisation—a scale of values centred around the sacrosanct two-legged mammal?

Of myself, if I love ‘all men’, I won’t use any of them; I won’t take any of them ‘as a means’, for an end which is not him. You don’t exploit what you really love. This is a psychological law.

But no ‘reason’ can force me to ‘love all men’—any more than it can force most men to love all animals. Kant’s ‘reason’ ordered him not to exploit any human being, not because this is a universal commandment, but because he loved all men, like the good Christian he was. I, who do not love them all, do not feel that this ‘duty’ concerns me. It is not my duty. I refuse to submit to it. And if a man who finds the exploitation of animals and trees—and what exploitation!—quite natural, dares to come and preach me about ‘respect for the human person’, I would brutally send him to mind his own business.

______ 卐 ______

Editor’s Note: This is more than fundamental. If there is something that my work From Jesus to Hitler teaches, it is that we must stop loving the vast majority of humans to save the nymphs of the sidebar and the animals under the human yoke.