What to do in case of mental disorder

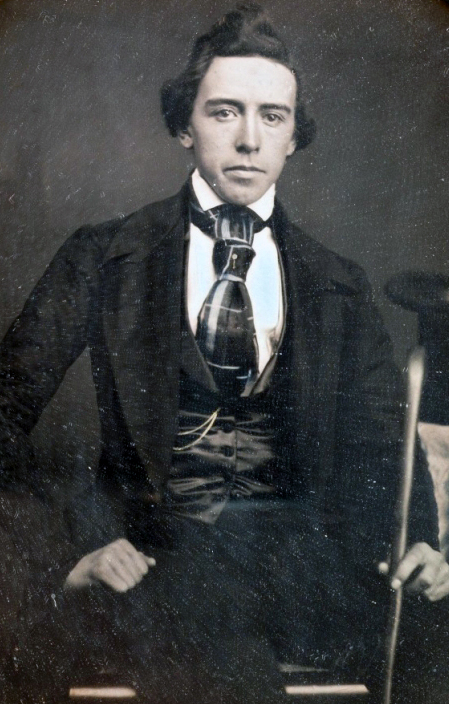

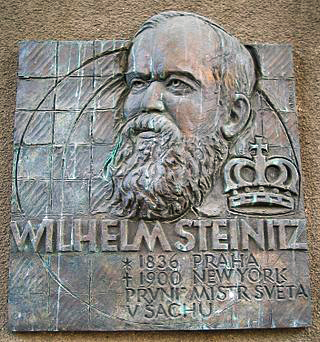

Surprising in such prolific chess literature as that of the United States is the absence of biographies that explain the mental disorders of their chess champions: Morphy and Fischer. I have complained about friends in the park who lacked the heart to inquire about the personal tragedies of Roger, Iván, Gilberto and Ricardo. For example, I don’t remember hearing anything pertinent about the scar that Gilberto wore on his face due to the blow of the dish thrown by his mother. But this is not limited to my acquaintances: it is endemic outside the chess field. In writing this essay, I tried to search the internet for biographical material on Morphy, Steinitz and Torre. I was surprised that the attitude of the authors of books and web pages was identical to that of friend Antonio, whose supposed friendship was ‘to talk exclusively about chess’.

A section from the fourth volume of Kasparov’s five-volume collection of his predecessors is an exception, in that it portrays Fischer through astonishing anecdotes. Although Fischer’s feat from 1970 to 1972 is admirable from a strictly sporting viewpoint, it’s impossible to read those pages without thinking that Fischer was, in his personal life, a poor devil. Do you know, my dear readers, someone who could have had fame, money and glory and throughout the years threw that opportunity away as Fischer did? It is worth reading Kasparov’s My Great Predecessors, Volume 4 and finding out what happened to poor Bobby after he triumphed over Boris. I am referring to the final pages that are already free of game analysis and focus, pace the friend Antonio, on the human side of chess; in this case, Fischer’s psychological profile. However, and like Reinfeld, Kasparov knew nothing about the morbidity of family dynamics that can flourish in the adult in the form of psychosis.

Not even psychiatrists know these things.

If mental health professionals, or American chess writers, were down to earth they would try to write psycho-biographical studies on Morphy and Fischer. But when it comes to psychological trauma, it is impossible to find an in-depth analysis of those who have suffered this type of crisis. In this aspect my work is innovative. It seems that I am the first person in history who has devoted more than a thousand pages to pondering the tragedy of his own family (see the titles of my books on page 3).

To the names of deranged chess masters I have mentioned I might add Pillsbury. And let’s not forget the alcoholism of Chigorin, Alekhine and Tal. Former world champion Tal and his buddy Korchnoi, who was on the verge of taking the title from Karpov in 1978, were badly beaten up in Cuba for being drunk. Once Alekhine showed up to a simultaneous exhibition so drunk that he wet himself on the floor and the show had to be suspended. The numerous chess magazines circulating in endless languages are as misleading as Velasco’s book on Torre. They focus on the sporty aspect omitting the real life of the pathetic players.

The total lack of knowledge of the human mind in both psychiatrists and chess players is evident in the sovereign folly of blaming Staunton, a retired player in his day, for Morphy’s madness. I find it regrettable that even Reinfeld repeats this like a parrot. Ironically, it was thanks to Reinfeld’s book that I learned that it was Morphy’s mother who forbade her son from playing in public places again, and the best player in the world obeyed like a child. Also the professional chess writers Horowitz and Rothenberg repeat the Staunton myth in The Personality of Chess, where they quote the incredibly stupid words of Ernest Jones, Freud’s disciple, that Morphy was burned out by success. Based on the Freudian axiom of exonerating the abusive father or mother, Jones blames Staunton, who Morphy never played with! His crazy theories appear in the essay ‘The Problem of Paul Morphy’ published in 1931: a classic in psychoanalytic literature on the chess player. In Mexico, a country where the refutation that has been made to the Vienna quack, Freud, is unknown, I have found the fans repeating Jones’ nonsense.

Thus I arrive at the central question: What to do in case of mental disorder of a loved one? What to do, for example, if he gets naked on the streets or surround himself with women’s shoes?

With psychiatry ruled out as an iatrogenic profession, the good news is that we have the humanitarian alternative of Soteria Houses in Europe.

Unlike the therapy applied to Torre, which impaired his faculties and left him resentful for life with Ferriz, entering the Soteria Houses is perfectly voluntary. In the United States, those precincts flourished thanks to public funds before Big Pharma lobbied for the subsidies to be withdrawn. (The multibillion-dollar companies that manufacture drugs don’t tolerate competition from their medical model for treating disorders of the spirit.) In the Soteria-type houses that exist in Europe, the dignity of those who suffer a crisis is not violated. Neither you will find treatments such as electroshock, surgical lobotomy or intellectual impairment practised by chemicals euphemistically called ‘antipsychotics’. No matter how serious their delusions are, the person is respected and a friendly environment is provided until, after some time of good treatment, they can regain their senses.

Generally, people who get disturbed are not dangerous. Steinitz believing in his telekinetic powers, Torre imitating St. Francis or Morphy declaiming on the roof ‘and the little king will walk away in shame’ were harmless. Had they lived for a few months in a Soteria House, similar to the quarters for the alienated of the 19th-century Quakers, they would have recovered. There are no Soteria houses in Mexico, although the last Robert Whitaker’s video that I’ve watched now that I review this book, ‘The Rising Non-Pharmaceutical Paradigm for Psychosis’, shows us that alternative in first world countries:

When I advanced the idea of renting in Mexico City an apartment to take care of a friend of Russian descent along with an assistant (a young man who was disturbed), his older brother’s response was to commit him to a repressive institution, where he died. It is sad to say: but psychiatric repression is originated from family repression (Morphy’s family, too, wanted to commit him). That flat would have been cheaper for our friend than the psychiatric fees he paid. But the deference in the West to the medical profession is too ingrained. I hope that the way the medical establishment behaved now that I review this book, with all that media cancellation of the effectiveness of ivermectin for the treatment of COVID-19 (to profit from Big Pharma vaccines), begins to wake up part of the population.

There are very few thinkers who have an exact idea of how the interests of pharmaceutical companies corrupt medical science. And this especially includes psychiatry. It was for this reason that I spent five years of my life, full time, researching the profession.