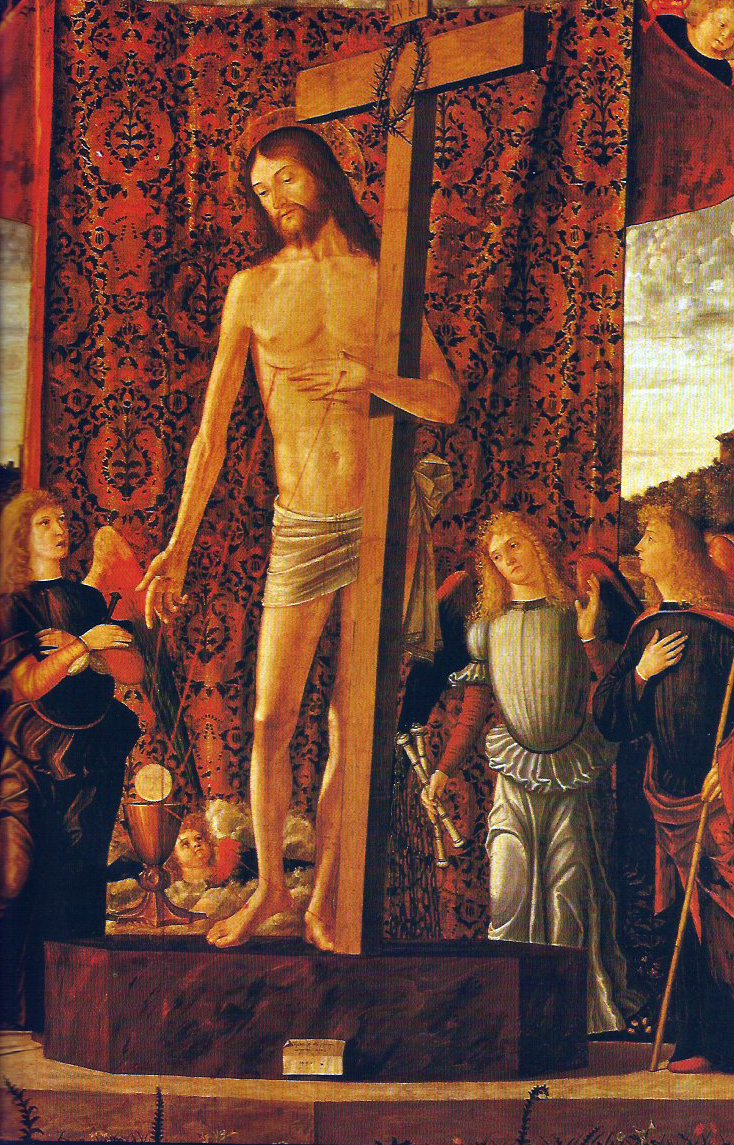

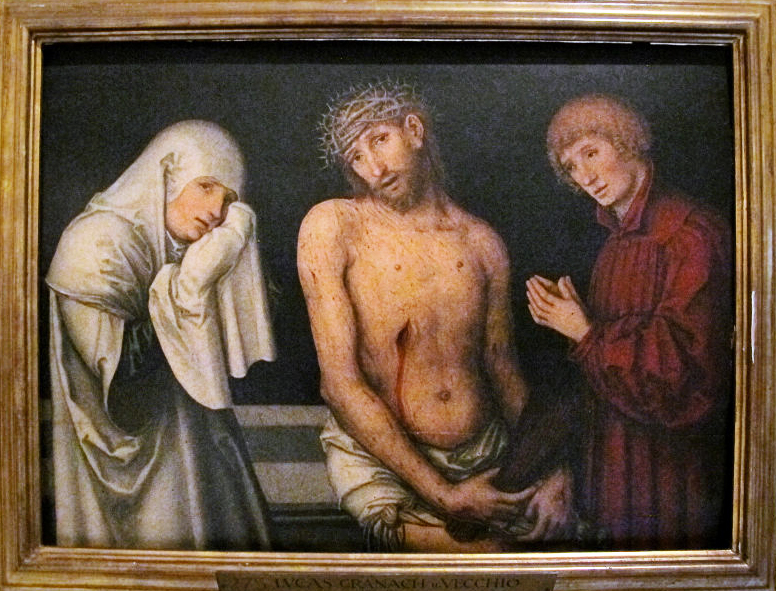

The ‘Man of sorrows’, as Isaiah prophesied in one of the holiest books of the Jews, is one of the great images of the suffering Christ.

The ‘Man of sorrows’, as Isaiah prophesied in one of the holiest books of the Jews, is one of the great images of the suffering Christ.

Crushed by the sufferings and in an attitude of giving himself, Giovanni Bellini seems to have interpreted him in this Pietà, Dead Christ Supported by Two Angels (1460) in Venice’s Correr Museum.

Real history was the opposite to this lamb who gave himself to sacrifice. Real-life Christians martyred and sacrificed the Aryan religion to impose on whites the god of the Jews. In ‘The Saxon Savior: Converting Northern Europe’ Ash Donaldson said:

______ 卐 ______

Into the North

The missionaries to the North, carrying out Christ’s injunction to baptize all nations, encountered a preaching environment utterly different from the Mediterranean. Here there were no large cities and no alienated, deracinated masses eager for something to give their lives purpose. Whether we use the term pagus or polis, the peoples of the North clearly lived in the type of communities Aristotle regarded as ideal: small, self-governing, and bound by common kinship, religion, language, and history.

The greatest difference of all, which perhaps encompasses all the rest, is that these people knew who their ancestors were. The line from which each individual sprang was not an unknown quantity to him—a faceless crowd that had bequeathed him nothing and to which he owed nothing—but a sacred lineage of names and deeds that ultimately issued from deity itself. These people did not hunger for an artificial family and tribe, for the one they had was dear to them.

This dramatic difference is illustrated by the attempt to convert Radbod, King of the Frisians. Intrigued by this religious force that had apparently swept through every land, he was curious as to what it had to say of his own ancestors. Told rather blithely that the unbaptized were in Hell, he immediately dismissed the missionary priest, declaring he would rather spend eternity in Hell with his ancestors than in Heaven with his enemies.

To absorb peoples apparently immune to the siren-call of universal brotherhood, the Church employed two other tools: physical violence and religious syncretism. Zealous authorities had employed both in the Roman Empire, but on nothing approaching the scale they would in Northern Europe. Because the communities of the North were stronger and more confident, the conversion process was far more violent than it had been in the Mediterranean, although the peacefulness of its spread in the Empire has been exaggerated.

Editor’s note: Donaldson is here completely ignorant about the extremely hostile, ISIS-like, takeover by the Christians of the Roman Empire, as we have been discussing with the texts of Deschner and Nixey. Apparently Donaldson has not even read the masthead of this site, authored by the blogger Evropa Soberana.

The beheading of 4,500 Saxon nobles by Charlemagne in 782 was far from exceptional: witness, for instance, the career of St. Olaf, whose tortures his Christian biographers quite readily detail.

Recently, historians such as Robert Ferguson have even suggested that the entire period of Viking raids began as an asymmetric resistance to the violent conversion efforts undertaken by Charlemagne. Even the adoption of Christianity by Iceland, long presented by historical apologists as the poster-child for peaceful conversion, took place under the threat of armed invasion by the King of Norway, who also held several prominent Icelanders hostage during the negotiations at the Althing.

In the Mediterranean, men like St. Augustine had engaged in intellectual combat with intellectuals who adopted a fashionable skepticism toward the old Gods. [Cf. my comment above—Ed.] In the North, the combat was often real, and the missionaries’ audience had little patience for the idea that the old Gods did not exist, which sounded as plausible as denying their ancestors’ existence—especially since, as told in works like Rígsþula, the Gods were their ancestors.

And so the missionaries tacitly acknowledged the heathen Gods, but introduced the “White Christ” as a stronger entity. In Iceland, for instance, the Saxon missionary Thangbrand did not try to convince the Icelanders that the Gods didn’t exist, but argued that they were no match for Christ. We find this curious exchange with a heathen woman:

“Have you heard,” she said, “that Thor challenged Christ to a duel and that Christ didn’t dare to fight with him?”

“Wha I have heard,” said Thangbrand, “is that Thor would be mere dust and ashes if God didn’t want him to live.”

As if to prove the point, during one duel in his blood-soaked mission, Thangbrand used a cross to kill a man.

More important than the violence was the purpose it served, for the actual wielders of the sword were less interested in the fate of their enemies’ souls than in the consolidation of royal power. From the deification of the emperors to Constantine’s cooption of the Church, it had long been recognized that religious standardization made it easier to rule, especially if the centers of religious life were under the watchful eye of the ruler. Throughout the North, Christianity’s representatives did not win by appealing to some disenfranchised lumpenproletariat, but by emphasizing the services the Church could render to Caesar. Thus, in Scandinavia, the official conversion paralleled the emergence of centralized kingdoms and the erosion of local liberties.

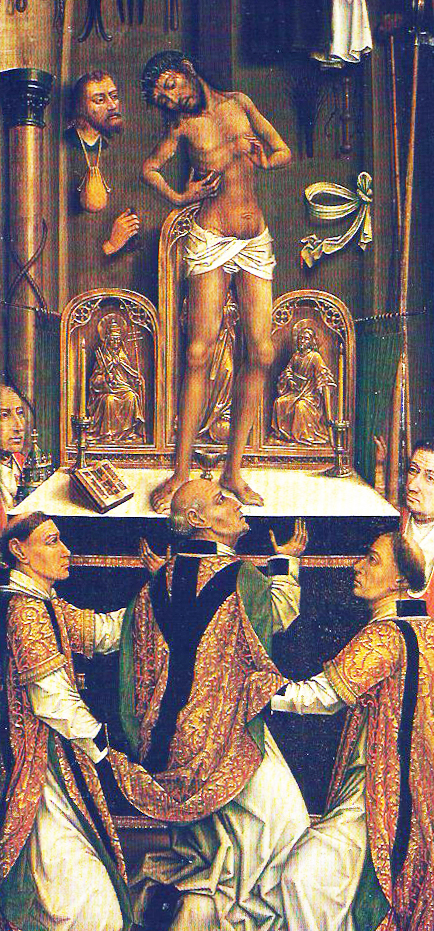

But while violence might win obedience, it could not win belief. To accomplish the latter, missionaries turned to syncretism. While the Church had employed this, too, in the Roman Empire, such as adopting the vestments and titles of the old pagan Pontifex Maximus, the need was much greater in the North, where people maintained strong ties to their ancestral ways. So, for instance, the Irish were given St. Brigid, with the same feast-day and associations as their Goddess by that name. Pope Gregory urged St. Augustine of Canterbury to let the Anglo-Saxons keep their sacred groves and feasts and merely repurpose them, while the more zealous St. Boniface cut down the sacred tree known as Thor’s Oak and used its wood to make a church.

These examples of syncretism are easy to spot, but more often the process was subtle. In Njal’s Saga, for instance, one of the Icelandic chieftains is considering conversion and asks if he can have the archangel Michael as his guardian angel, as the term is usually rendered in English translations. As Stephen McNallen points out, the Old Norse word the chieftain uses is actually fylgja-engill, prefacing the new, foreign word “angel” with the pagan word for a type of guardian spirit of the kin-line, or tribe.

By a similar process, the missionaries combined the Hebrew word for the ultimate destination of the wicked, Gehenna, with the Norse word for the pleasant meadows where the dead are reunited with their ancestors, Helja. After centuries of association, Gehenna was dropped, and Hell alone sufficed to induce shudders in the descendants of those who had happily looked forward to such a destination. The most ambitious effort of syncretism was an entire reconfiguration of the Gospels for the Germanic mindset, in a form that would have perplexed—and mortified—St. Paul.