https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=97L_SJrPl6g

Tag: Germany

Carolyn on Kevin

In my previous post I wrote: ‘White nationalism is an impossible chimera between truths and lies, between courage and cowardice, light and darkness’. This abridged article by Carolyn Yeager on Kevin MacDonald supports my claim.

Kevin Macdonald recently participated in a videocast of “Torah Talk” with Luke Ford, a non-Jewish student of Torah and Talmud, and two young friends or students of his. It lasted one hour and 50 minutes and resulted in some interesting insights into Kevin’s limitations as a leading White Nationalist voice.

Kevin Macdonald recently participated in a videocast of “Torah Talk” with Luke Ford, a non-Jewish student of Torah and Talmud, and two young friends or students of his. It lasted one hour and 50 minutes and resulted in some interesting insights into Kevin’s limitations as a leading White Nationalist voice.

MacDonald was taken by surprise with the first question asked of him: What are your thoughts about holocaust revisionism?

Yeah, um, I guess I’m not, uh, I’ve never had any sympathy really, before—I, I haven’t seen, I haven’t seen anything that I would really, you know, convince me. And I have—frankly, I haven’t dealt into it very much. My view is that it’s not important for what I’m doing and I don’t think it’s really important—I, I think what’s really important is the culture of the holocaust, you know how it’s taught in school, how it’s used to defend Israel, and it’s used as a weapon against people who oppose immigration, and all those things—ah I think those are very important things to discuss. So whether it actually happened, exactly [slurs some words] and all that is something that I don’t think uh is possible to even go there anymore, is just… just uh… third rail.

Hey, wait a minute! Is this the reputedly brilliant professor of evolutionary psychology speaking??? This sounds not only downright dumb but also evasive as hell.

- I’ve never had any sympathy

- Never seen anything that convinced me

- Don’t think it’s really important

- Haven’t dealt into it very much (weakening the above three comments, if not nullifying them altogether)

- Not possible to “go there anymore”

Not possible to go there anymore? But then he adds… “third rail.” He should have added the word “comfortably”—it’s not possible to go there comfortably, without putting oneself at risk. By that he signals premature defeat: The Jews have won on this and we have to allow them their victory. It’s too late to do anything about it. The price exacted is too high. By calling it “third rail” he’s dubbing it too dangerous, too highly charged for any sensible man to approach.

Are these brave men or foolish men? Kevin clearly considers them foolish, and maybe not too bright. He’s saying that what he’s doing is important but what they’re doing is not important.

- What’s really important is the culture of the Holocaust

But wait a minute! If the Holocaust didn’t happen, how can a “culture” of it exist? Or the trappings of such a culture be justified? So he obviously thinks the Holocaust did happen, or believes he must accept that presumption, but doesn’t want to come right out and say so. Because? Because so many listening to him would argue with him about it.

I’m afraid we have caught our evolutionary psychologist in a posture of dishonesty here. I know it has been our position to give Kevin a free pass on this subject, one that goes like this: He has shown so much courage in standing up to the accusations of antisemitism at his university; if he doesn’t want to get into even more trouble over “holocaust denial,” he certainly doesn’t have to. That was a position I myself took back when I had an Internet radio show on which he was a guest four times. I did not even bring it up.

But now he is retired and it is only his professional reputation at stake, not his job. And he is being asked these questions and he is answering them (see here). And I have revised my thinking about giving others so much leeway to think as they want about it. We need all hands on deck on this issue. In Kevin’s case though, I think it would be better were he to simply say, “I’ve made it my practice not to speak about this topic which I have not studied,” and leave it at that, rather than put forth uninformed opinions as he’s doing. Of course, that would be wimpy but at least not dishonest.

But perhaps he’s afraid that would cause his peers to suspect him of being a secret denier, which he clearly does not want. So instead he hems and haws around about “importance”—that the “culture of the Holocaust” has importance while the “happening of the Holocaust” doesn’t.

That’s an odd position. Maybe we can find some insight into his thought process in his answer to the next question asked him: What are your personal feelings toward Hitler?

Toward who? Oh God, I think that the only term I can use is a disaster. I think that his own personality—I just don’t know much about it but I think his own personality got in the way of them carrying out their strategic military [goals?] in World War Two. I think he was, you know, he thought of himself as a general or something. You know, he interfered with policy that should have been left to professionals and I think that that was a—you know, that was horrible, that was a disaster. There are a lot of other things, but uh, so I think that he is not the ideal person to be in that situation.

- Hitler was a disaster

- Don’t know much about it

- Interfered with military policy

His reactions toward Hitler are more vehement than toward Holocaust. They reflect the standard Anglo narrative that Hitler bungled the war, that his generals despised him, he was a flawed personality who all by himself created the disaster that occurred in Germany. No fault is directed toward Jews, or the Allied collusion with Major Jewish Organizations, or the German traitors (including in the Wehrmacht) who conspired to defeat their own country and turn as many people as possible away from their leader. As MacDonald said, he doesn’t know much about it, but the “common American wisdom”, the national narrative, is good enough for him. But then he has a few second thoughts:

But you know, having said that, if you look at the old newsreels from 1930’s in Germany, you know, the people loved Hitler and he really managed to develop a sense of sort of a very unified, culturally unified nation. Uh, they were really on page with this, and I think that was an incredible accomplishment. It’s just unfortunate how they used it, what happened in the end. Just a disaster. I-I think that is the—the, uh, the result of the Second World War is uh has essentially given us the war that we’re in now. I think the triumph of the Left is the result of WWII. I think uh is also um critically important for the rise of Jewish influence. And that is what is now with us. And can’t be undone.

- Hitler was loved by the people

- Unified the nation

- Incredible accomplishments

- The war was a disaster

Amazing. Kevin goes from admiring how Hitler unified the nation, an incredible feat, directly to the misuse of it, though he doesn’t explain how they misused it. Apparently by going to war. As though Hitler could have avoided war, with Stalin plotting to his east and Roosevelt plotting from the west (see the Potoki Papers). For some reason (we know what it is), he accepts the non-mention of the Jews behind the scenes in all this. MacDonald’s simplified history credits the triumph of the Left and the rise of Jewish influence (which are one and the same) as being brought about by Hitler’s ‘disastrous’ war. Does he have any idea how strong the Left was in Germany when Hitler started? It was an actual revolution that resulted in a communist government for a time in Bavaria!

Jews were already in a strong position since WWI. So our Kevin is not much of an historian of this period and, here again, should be answering, “I don’t know.”

The final questions in this series are:

What kind of world do you think we would have if the Axis had won?

It’s impossible to know. I uh I just don know. If the Axis had won, if they crushed the Soviet Union and then occupied Britain, um there probably would have been a stand off at that point. And then I do think it would have been bad for the Jews, in Europe, if that had happened. But I don’t think Europe would be overrun as it is now with all these non-Whites. I think Europe would have remained a White, Christian-based civilization if that had happened. I—That’s my best guess.

- Bad for Jews

- Europe still a White, Christian-based civilization

It sounds like he wishes the Axis had won and now blames Hitler for failing to pull it off.

Do you think there is any hope for Europe at this point, or what do you think would have to happen to fix the situation?

For Europe? You’d have to have a complete change in mental outlook, uh you’d have to have the political will to do something. They could still do something but it’s getting, you know, they don’t and it just keeps getting worse and worse. And I think everybody go—you know, the popular opinion polls do reflect anxiety about it, concern, uh, and yet they can’t seem to vote in a government that will actually do something.

So until that happens… um… they could still do it, I mean the percentages of Muslims in France and the West German countries in Europe (sic) are still pretty small. They could do something. They could just deport. Really, I mean a lot of them have no right to be there. The so-called refugees, they can go back to wherever they came from. They can repatriate these people. It just takes a political will which they are a very long way from being there.

So until that happens, it’s just going to fester and there’s going to be more and more anxiety, and more and more disillusion with these elites… But, I’m amazed at the staying power of… it did look with Brexit, Trump victory and now… but then you see you’ve got the victory of Macron in France, so… and Wilders got defeated very badly in the Netherlands, the Swedish government doesn’t seem to be going away. It looks like Merkel’s going to win in Germany, so it doesn’t look (chuckles wryly) that anything’s really changed.

- Need complete change in mental outlook

- No mention of removing Jews

- No political will even for removing Muslims

- Voters falling short

Notice he doesn’t mention anything about Jews as a problem, only Muslims. Is that a problem with mental outlook? He said later in the program, speaking of white nationalists he approves of (like Jared Taylor)—when they get together they “don’t talk about gas chambers” (said somewhat sneeringly), they talk about white interests. Understand this as: We are not “disasters” like Hitler, who did have the political will to carry out an anti-Jewish policy. For them the Jews are here to stay because there’s no will to do anything about it. They’re grappling with the Muslims now. They can live with the Holocaust.

@40 min. participant Casey said: “I had to watch Schindler’s List in 8th grade, but that was it. But I got it—Hitler’s a bad guy.” His question: How to change education to give kids a more complete historical context, for example like what was happening in Weimar?

Kevin answers by shifting to Blacks and Slavery, away from holocaust.

@46 min. Luke Ford asks: A line from an article you published was “Jews are genetically driven to destroy Whites.” Is that a fair description?

Kevin: No, it’s not. I wrote a book called Culture of Critique—it’s about culture, not genetics. How they identify themselves, think about themselves. I would like to see a cultural shift.

Luke added: Andrew Joyce wrote in an essay published at TOO: “The Jews of the middle ages did no labor—almost all lived parasitically from money-lending.”

Kevin did defend this, but said, “I don’t use the word parasite… much… I don’t think you can use that word for American Jews.”

@1 hr 44 min. Kevin: “I don’t like people who have swastikas on their websites; identify with Nazism. It’s a non starter in American context. We have to be an American party, we have to be about white people, and we have to give up the sort of National Socialist idea of the past. Which was a disaster, partly of its own making. I don’t think it was well led. So we have to get away from them. It’s just bad PR.”

Kevin MacDonald tries to act casual when it comes up in interviews, but he is clearly not casual in his feelings about it. He is incredibly careful of leaving any opening for an association with him and Holocaust revisionism. By doing so, he helps the Jewish drive to keep Germans forever guilty of “unspeakable” and unnatural crimes, and unable to rise (“on their knees” as it’s been coined); which in turn helps the Jewish drive to wield their weapon of antisemitism against all Europeans; which in turn hinders all whites from feeling enough pride to defend their race because the one who is most famous for doing so is seen as a disaster to his race by his own people. But of course, Kevin would deny all this.

If Whites could stick together and work together on Holocaust revisionism, I believe success could be had. I don’t know of a single person who, willing to really look at the evidence and give it a chance, continued to believe the official narrative of the big H. It’s always a political decision to insist that it must have taken place because too much is a stake politically if it didn’t. The entire WWII global order would be shaken to its core. This is the position MacDonald is in, it seems to me, along with so many other White activists who say they put White survival and sovereignty first. They don’t. They are afraid some element in the social fabric that they don’t like will get control, and that bothers them more than giving control to the non-White. This is incredible but true.

During this program, Kevin spoke of how some anti-Jewish material he reads “makes him sick,” he didn’t want to think he played any part in encouraging it. However, he was quite easygoing when it came to the subject of Jewish behavior—no similar strong feelings emerged. He thought some Jews were aligned with White interests and could participate well in White societies. Clearly it is a matter of culture for him.

In closing, I have seen again and again that behind the reluctance to confront the Holocaust taboo lies the stronger fear of the Adolf Hitler taboo. Many truly believe the propaganda that Hitler was a disaster for Europe, thus to keep anyone like him from returning to power, Hitler must remain the one responsible for the horrible Holocaust and the Holocaust must remain real. What they don’t seem to consider is that as Germans disappear as a consequence, Europe will die along with them. Without a genuine Germany, there is no Europe.

Siege, 10

Playing the ball as it lies

“We are a parliamentary party by compulsion”, said Adolf Hitler during the Kampfzeit period in Germany from 1925 to 1933. Because Germany was still essentially sound under the surface in 1923, the open revolt did not work, nor catch on with the populace (apart from being betrayed from the inside by conservative swine). And because German society and institutions were still basically sound at that time. Hitler and his fellow Putschists were looked upon quite sympathetically and favorably by those presiding at their trial in 1924 which resulted in less than a year’s incarceration. (That German court gave Hitler less than a year for “high treason”; the System here today gives patriots fifty years for charges they were framed on, for doing nothing!)

What had prompted the Munich Putsch was the apparent bottoming-out of German law-and-order and economy. But that drastic move was premature because the Weimar regime—filthy and rotten as it was—still had more than one gasp left in it. The economy actually rallied from that point up until the World Depression of 1929 which sent a stampede of desperate Germans, no longer complacent, into the ranks of Hitler’s Party.

The point is that German institutions were yet healthy enough to work within, and indeed too healthy to try to overthrow (as the Communists had already found out the hard way). The problem was a thin coating, or scum, if you will, of traitors at the top. Because of Hitler’s correct assessment of the situation and the firm course he set his Party on accordingly in 1925, the history of the NSDAP from then until the Machtergreifung—the taking of state power—is an unbroken, uninterrupted uphill climb.

We of the NSLF are a revolutionary party by compulsion. We are the first to realize that no popular revolt can be contemplated at this time as the only thing “popular” at the moment is further pleasure and more diversion among the quivering masses. The society is a shambles and the economy slips more every day but most would—and will—be surprised to learn just how much further it can deteriorate before the situation can be termed critical.

We also realize that nothing, absolutely nothing by way of Anglo-Saxon institutions remain intact and this effectively means that America as it had been known for about 150 years has been wiped out more cleanly than if it had been defeated in a sudden war. (This actually had been Germany’s case and was what had allowed for her resurrection within only fourteen years.) The United States went the worst way a country can—terminal cancer—but yet, historically, even that process was quick—quick enough to leave enough White Men with some ability to still think and act as White Men. The rest is up to us.

The polarization of the people and the government is so total that few even among the Movement can grasp its fullness. Perhaps the best way to be sure that we are the prime representatives of the people is to be aware that NO ONE is further alienated from the ruling, governing establishment than we. We call ourselves a LIBERATION FRONT and not a party because we hold no illusions about ever being able to realize anything concrete through parliamentary measures.

How could such a movement succeed when the people themselves don’t care and the ruling body—Left, Right, and Center—unanimously stonewalls against us? The voices and opinions of the System might put forth varying opinions on any topic or issue save one: US. We are now and forever strictly O-U-T! But we know why we are out and they know why we are out so there should be no conflict on that. They are the Establishment; we are the Revolution.

These are the rules, of their choosing, not ours. But they are the reality of a situation as harsh as it is immutable. It is war. Only a fool and a weakling would ask for it to be otherwise. The one fundamental reason the Hard Right movement in this country has perennially gone nowhere is because it has NEVER fully comprehended this one fundamental reality and has never been set upon the proper course as was Hitler’s movement in Germany.

To describe the past twenty-odd years of Rightist and even Nazi effort in the United States as inappropriate is to put it as accurately and charitably as possible. Set upon an inappropriate course, with inappropriate ideals and priorities, inappropriate methodology, etc. —little wonder then why we have been plagued with such miserably inappropriate and wholly inadequate human resources. It is the reason quality human material doesn’t stay around long. The Movement has been off-base at the very foundation which means that no matter how carefully or skillfully the framework might go on, it is all fore-doomed to collapse (as it always has done).

There has always been the talk of a New Order and a New World. Those are easy slogans, too easy in fact because their meaning is mostly lost. Their meaning directly implies a TOTAL CHANGE. Given the graduality of the decline of American society and culture over the past thirty or forty years, it’s hard for any comparatively young person to appreciate how far we’ve sunk and to know from that just what we’ve lost, and what must be recaptured and through National Socialist discipline and idealism enhanced and reinforced, super-charged to become something greater than has ever been seen on earth. Even Hitler did not face a task such as we face.

Being aware of this then, the notion of even attempting or remotely desiring to become a part of the unspeakably vile and sick Establishment and System is utterly revolting to any true National Socialist. To sit amongst the sold-out and degenerate Senate and Congress in the Capitol?! Even Hitler refused to seat his new government in the same halls as the Weimar regime or the Imperial government (liberally laced as it was with Jews). He wanted a new beginning. Our enemies are VILE and only appear “legitimate” because of the power that comes with money. We state here and now that we shall SMASH THEM and, furthermore, that they are HELPLESS TO PREVENT IT! The road may be long and rocky but the moment will arrive and both our will and our striking blows shall be irresistible.

No recognition and no cooperation today means no compromise and no quarter shown tomorrow. No favors rendered today means no obligations to fulfill tomorrow. Not asking today means not being told tomorrow. If we do not accept and function by the circumstances as they exist, we not only condemn ourselves to eternal failure but we miss the opportunity now given for a revolution more total and complete than anything ever before in all history.

Vol.X, #1 – January, 1981

Order a copy of Siege (here)

Antisemitism

by Joseph Goebbels

A passage from Der Nazi-Sozi, Elberfeld: Verlag der Nationalsozialistischen Briefe, 1927:

“You make a lot of noise about the fact that you oppose the Jews. Isn’t anti-Semitism outdated in the twentieth century? Isn’t the Jew a human being like everyone else? Aren’t there decent Jews? Isn’t it bad that we 60 million fear 2 million Jews?”

“You miss the point. Try to think logically:

If we were only anti-Semites, we would be out-of-place in the twentieth century. However, we are also socialists. For us, the two go together. Socialism, the freedom of the German proletariat and thereby of the German nation, can only be achieved against the Jews. Since we want Germany’s freedom, or socialism, we are anti-Semites.

Sure, the Jew is also a human being. None of us has every doubted that. But a flea is also an animal—albeit an unpleasant one. Since a flea is not a pleasant animal, we have no duty to defend and protect it, to be of service to it so that it can bite and torment and torture us. Rather, our duty is to make it harmless.

The same is true of the Jew.

Sure, there are decent (weiße) Jews. More of them every day. That however, is not evidence for the Jews, but rather it is evidence against them. The fact that one calls scoundrels among us decent “Jews” is proof that to be Jewish carries a stigma, else one would call deceitful Jews “decent (gelbe) Christians.” The fact that there are so many decent Jews proves that the destructive Jewish spirit has already infected wide circles of our people. It is encouragement for us to carry on the battle against the Jewish world plague wherever possible.

It is a bad sign for you, not for us, that 60 million fear 2 million Jews. We do not fear these 2 million Jews, but rather we fight against them. You, however, are too much of a coward to join this battle, and behave like a cat on a hot stove.

If these 60 million fought the Jews as we do, they would have nothing more to fear. It would be the Jews’ turn to fear.”

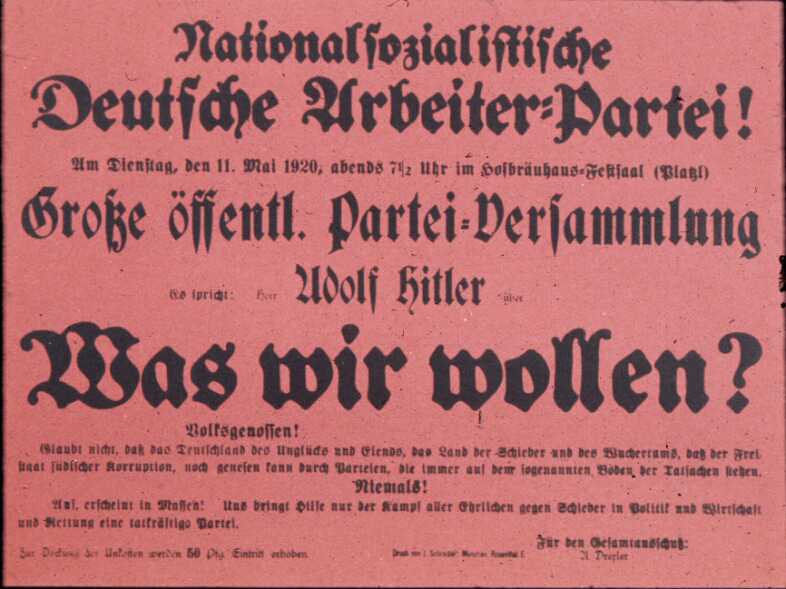

This poster announces a National Socialist meeting in Munich in May 1920. Hitler is to speak on the topic “What do we want?” The text below the title reads:

“Citizens! Do not believe that the Germany of misfortune and misery, the nation of corruption and usury, the land of Jewish corruption, can be saved by parties that claim to stand on a foundation of facts. Never!”

by Mike Maloney

Chapter Two:

The wealth of nations

In studying monetary history to identify cycles, it is necessary to examine both sides of the coin so to speak. The temptation is for people to blame all their woes on their government. Certainly governments are often at fault when it comes to inflation through fiat monetary policy, but one must never forget that in the end we are ultimately the ones who consent to our government’s rule. History is full of examples of greed leading a populace to do incredibly stupid things. Indeed, we don’t need government to ruin our economy. We can get by just fine by ourselves, thank you.

The best example I can think of is the tulip mania of 1637.

A tulip is still a tulip…

In order to understand the absurdity of this moment in history I’m about to share with you, you simply have to ask yourself: Would I pay $1.8 million for a tulip bulb? If the answer to that question is yes, then please put this book down and get some professional help. Otherwise, read on and see just how crazy the public can become.

Everyone thinks of tulips when they think of Holland. Then they think of beer. What many people don’t know is that tulips are not indigenous to Holland. They were imported. In 1593 the first tulip bulbs were brought from Turkey to Holland. They quickly became a status symbol for royalty and the wealthy. This developed into a mania, and soon a tulip exchange was established in Amsterdam.

Very quickly this mania turned into an economic bubble. You may find this comical; in 1636 a single tulip bulb of the Viceroy variety was traded for the following: 2 lasts (a last is 4,000 pounds) of wheat, 4 lasts of rye, 4 fat oxen, 8 fat swine, 12 fat sheep, 2 hogsheads (140 gallon wooden barrel) of wine, 4 tons of beer, 2 tons of butter, 1,000 pounds of cheese, 1 bed, 1 suit of clothes, and 1 silver goblet.

At its very peak in 1637 a single bulb of the Semper Augustus variety was sold for 6,000 florins. The average yearly wage in Holland at the time was 150 florins. That means that tulip bulbs were selling for 40 times the average Hollander’s annual income. To put that into perspective, let’s assume the average U.S. salary is $45,000. That means that a tulip bulb in today’s terms would cost you $1.8 million.

Soon people began to realize how absolutely crazy the situation had become, and the smart money (if you can call anyone involved in this mania smart) began to sell. Within weeks tulip bulb prices fell to their real value, which was several tulip bulbs for just one florin.

The financial devastation that swept across northern Europe as a result of this market crash lasted for decades.

John Law and central banking

Another great example of a society replacing its money with an ever inflating currency supply is the story of John Law. John Law’s life was a true roller-coaster ride of epic proportions.

Born the son of a Scottish goldsmith and banker, John Law was a bright boy with high mathematical aptitude. He grew up to be quite a gambler and ladies’ man, and lost most of his family fortune in the course of his exploits. At one point, he got into a fight over a woman and his opponent challenged him to a duel. He shot his opponent dead, was arrested, tried, and sentenced to hang. Being the knave that he was, Law escaped from prison and fled to France.

Meanwhile, Louis XIV was running France deeply into debt due to war mongering and his lavish lifestyle. John Law, who was now living in Paris, became a gambling buddy with the Duke d’Orleans, and it was at about this time that Law published an economic paper promoting the benefits of paper currency.

When Louis XIV died, his successor, Louis XV was only eleven years old. The Duke d’Orleans was placed as regent (temporary king), and to his horror he found out that France was so deep in debt that taxes didn’t even cover the interest payments on that debt. Law, sensing opportunity, showed up at the royal court with two papers for his friend blaming the problems of France on insufficient currency and expounding the virtues of paper currency. On May 15, 1716, John Law was given a bank (Banque Générale) and the right to issue paper currency, and there began Europe’s foray into paper currency.

The slightly increased currency supply brought a new vitality to the economy, and John Law was hailed as a financial genius. As a reward the Duke d’Orleans granted Law the rights to all trade from France’s Louisiana Territory in America. The Louisiana Territory was a huge area comprising about 30 percent of what is now the United States, stretching from Canada to the mouth of the Mississippi River.

At that time, it was believed that Louisiana was rich in gold, and John Law’s new Mississippi Company, with the exclusive rights to trade from this territory, quickly became the richest company in France. John Law wasted no time capitalizing on the public’s confidence in his company’s prospects and issued 200,000 company shares. Shortly after that the share price exploded, rising by more than 30 times in a period of months. Just imagine, in a few short years, Law went from a gambling addict and penniless murderer to one of the most powerful financial figures in Europe.

Again, Law was rewarded. This time the Duke bestowed upon him and his companies a monopoly on the sale of tobacco, the sole right to refine and coin silver and gold, and he made Law’s bank the Banque Royale. Law was now at the helm of France’s central bank.

Now that his bank was the royal bank of France it meant that the government backed his new paper notes, just as our government backs the Federal Reserve’s paper notes. And since everything was going so well, the Duke asked John Law to issue even more notes, and Law, agreeing that there is no such thing as too much of a good thing, obliged. The government spent foolishly and recklessly while Law was pacified with gifts, honors, and titles.

Yes, things were going quite well. So well, in fact, that the Duke thought that if this much currency brought so much prosperity, then twice as much would be even better. Just a couple of years earlier the government couldn’t even pay the interest on its debt, and now, not only had it paid off its debt, but it could also spend as much currency as it wanted. All it had to do was print it.

As a reward for Law’s service to France, the Duke passed an edict granting the Mississippi Company the exclusive right to trade in the East Indies, China, and the South Seas. Upon hearing this news, Law decided to issue 50,000 new shares of the Mississippi Company. When he made the new stock offer, more than 300,000 applications were made for the new shares. Among them were dukes, marquises, counts, and duchesses, all waiting to get their shares. Law’s solution to the problem was to issue 300,000 shares instead of the 50,000 he was originally planning, a 500 percent increase in the total number of shares.

Paris was booming due to the rampant stock speculation and the increased currency supply. All the shops were full, there was an abundance of new luxury goods, and the streets were bustling. As Charles Mackay puts it in his book Extraordinary Popular Delusions and the Madness of Crowds, “New houses were built in every direction, and an illusory prosperity shone over the land, and so dazzled the eyes of the whole nation, that none could see the dark cloud on the horizon announcing the storm that was too rapidly approaching.”

Soon, however, problems started to crop up. Due to the inflation of the currency supply, prices started to skyrocket. Real estate values and rents, for instance, increased 20-fold.

Law also began to feel the effects of the rampant inflation he had helped create. With the next stock issue of the Mississippi Company, Law offended the Prince de Conti when he refused to issue him shares at the price the royal wanted. Furious, the Prince sent three wagons to the bank to cash in all of his paper currency and Mississippi stock. He was paid with three wagonloads-ful of gold and silver coin. The Duke d’Orleans, however, was incensed and demanded the Prince return the coin to the bank. Fearing that he’d never be able to set foot in Paris again, the Prince returned two of the three wagonloads.

This was a wake-up call to the public, and the “smart money” began to exit fast. People started converting their notes to coin, and bought anything of transportable value. Jewelry, silverware, gemstones, and coin were bought and sent abroad or hoarded.

In order to stop the bleeding, in February of 1720 the banks discontinued note redemption for gold and silver, and it was declared illegal to use gold or silver coin in payment. Buying jewelry, precious stones, or silverware was also outlawed. Rewards were offered of 50 percent of any gold or silver confiscated from those found in possession of such goods (payable in banknotes of course). The borders were closed and carriages searched. The prisons filled and heads rolled, literally.

Finally, the financial crisis came to a head. On May 27, the banks were closed and Law was dismissed from the ministry. Banknotes were devalued by 50 percent, and on June 10 the banks reopened and resumed redemption of the notes for gold at the new value. When the gold ran out, people were paid in silver. When the silver ran out, people were paid in copper. As you can imagine, the frenzy to convert paper back to coin was so intense that near riot conditions ensued. Gold and silver had delivered a knockout blow.

By then John Law was now the most reviled man in France. In a matter of months he went from arguably the most powerful and influential force in society back to the nobody he was before. Law fled to Venice where he resumed his life as a gambler, lamenting, “Last year I was the richest individual who ever lived. Today I have nothing, not even enough to keep alive.” He died broke, in Venice, in 1729.

The collapse of the Mississippi Company and Law’s fiat currency system plunged France and most of Europe into a horrible depression, which lasted for decades. But what astounds me most is that this all transpired in just four short years.

The Weimar Republic—a painful lesson learned

By now you’ve learned the kind of damage fiat currency can cause. Now let’s look at another example and identify the silver lining (no pun intended), and how such extreme situations can actually present opportunities to acquire vast wealth.

At the beginning of World War I, Germany went off the gold standard and suspended the right of its citizens to redeem their currency (the mark) for gold and silver. Like all wars, World War I was a war of and by the printing press. The number of marks in circulation in Germany quadrupled during the war. Prices, however, had not kept up with the inflation of the currency supply. So the effects of this inflation were not felt.

The reason for this peculiar phenomenon was because in times of uncertainty people tend to save every penny. World War I was definitely a time of uncertainty. So even though the German government was pumping tons of currency into the system, no one was spending it—yet. But by war’s end, confidence flooded back along with the currency that had been on the sidelines, and the ravaging effects worked their way through the country as prices rose to catch up with the previous monetary inflation.

Just before the end of the war, the exchange rate between gold and the mark was about 100 marks per ounce. But by 1920 it was fluctuating between 1,000 and 2,000 marks per ounce. Retail prices shortly followed suit, rising by 10 to 20 times. Anyone who still had the savings they had accumulated during the war was bewildered when they found it could only buy 10 percent or less of what it could just a year or two earlier.

Then, all through the rest of 1920 and the first half of 1921, inflation slowed, and on the surface the future was beginning to look a little brighter. The economy was recovering, business and industrial production was up. But now there were war reparations to pay, so the government never stopped printing currency. In the summer of 1921 prices started rising again and by July of 1922 prices had risen another 700 percent.

This was the breaking point. And what broke was people’s confidence in their economy and their currency. Having watched the purchasing power of their savings fall by 90 percent in 1919, they knew better this time around. They were smarter; they had been here before.

All at once, the entire country’s attitude toward currency changed. People knew that if they held on to their currency for any period of time they’d get burned… the rising prices would wipe out their purchasing power. Suddenly everybody started to spend their currency as soon as they got it. The currency became a hot potato, and no one wanted to hang on to it for a second.

After the war, Germany made the first reparations payment to France with most of its gold and made up the balance with iron, coal, wood, and other materials, but it simply didn’t have the resources to meet its second payment. France thought Germany was just trying to weasel its way out of paying. So, in January of 1923, France and Belgium invaded and occupied the Ruhr (the industrial heartland of Germany). The invading troops took over the iron and steel factories, coal mines and railways.

In response, the German Weimar government adopted a policy of passive resistance and noncooperation, paying the factories’ workers, all 2 million of them, not to work. This was the last nail in the German mark’s coffin.

Meanwhile, the government put its printing presses into overdrive. According to the front page of the New York Times, February 9, 1923, Germany had thirty-three printing plants that were belching out 45 billion marks every day! By November it was 500 quadrillion a day (yes, that’s a real number).

The German public’s confidence, however, was falling faster than the government could print the new currency. The government was caught in a downward economic spiral. A point of no return had been passed. No matter how many marks the government printed, the value fell quicker than the new currency could enter into circulation. So the government had no choice but to keep printing more and more and more.

By late October and early November 1923, the German financial system was breaking down. A pair of shoes that cost 12 marks before the war now cost 30 trillion marks. A loaf of bread went from half a mark to 200 billion marks. A single egg went from 0.08 mark to 80 billion marks.

The German stock market went from 88 points at the end of the war to 26,890,000,000, but its purchasing value had fallen by more than 97 percent.

Only gold and silver outpaced inflation. The price of gold had gone from around 100 marks to 87 trillion marks per ounce, an 87 trillion percent increase in price. But it is not price, but value, that matters, and the purchasing power of gold and silver had gone up exponentially.

When Germany’s hyperinflation finally came to an end on November 15, 1923, the currency supply had grown from 29.2 billion marks at the beginning of 1919 to 497 quintillion marks, an increase of the currency supply of more than 17 billion times. The total value of the currency supply, however, had dropped 97.7 percent against gold.

[Note of the Ed.: In his books and audiovisual materials, Maloney loves charts. In “Chart 1. Price of 1 Ounce of Gold in German Marks from 1914-1923” he depicts the Weimar Republic hyperinflation from one to a trillion paper marks per gold mark. We won’t be reproducing his charts in this site, but the curious reader can see them: here.]

The poor were already poor before the crisis, so they were affected the least. The rich, at least the smart ones, got a whole lot richer. But it was the middle class that was hurt the most. In fact, it was all but obliterated.

But there were a few exceptions. There were a few who had the right qualities and cunning to take advantage of the economic environment. They were shrewd, adept, and nimble, but most of all, adaptable. Those who could quickly adapt to a world they had never seen before, a world turned upside down, prospered. It didn’t matter what class they came from, poor or middle class, if they could adapt, and adapt well, they could become wealthy in a matter of months.

At this time, an entire city block of commercial real estate in downtown Berlin could be purchased for just 25 ounces of gold ($500). The reason for this is that those who held their wealth in the form of currency became poorer and poorer as they watched their purchasing power destroyed by the government. On the flip side, those who held their wealth in the form of gold watched their purchasing power increase exponentially as they became wealthy by comparison.

Here is the important lesson: During financial upheaval, a bubble popping, a market crash, a depression, or a currency crisis such as this one, wealth is not destroyed. It is merely transferred. During the Weimar hyperinflation, gold and silver didn’t just win, but smashed their opponent into the ground, by delivering yet another devastating knockout blow to fiat currency. Thus, those who held on to real money, instead of currency, reaped the rewards many times over.

We demand

by Joseph Goebbels

The following essay was published in the fourth

issue of Der Angriff, dated 25 July 1927.

The German people is an enslaved people. Under international law, it is lower than the worst Negro colony in the Congo. One has taken all sovereign rights from us. We are just good enough that international capital allows us to fill its money sacks with interest payments. That and only that is the result of a centuries-long history of heroism. Have we deserved it? No, and no again!

Therefore we demand that a struggle against this condition of shame and misery begin, and that the men in whose hands we put our fate must use every means to break the chains of slavery.

Three million people lack work and sustenance. The officials, it is true, work to conceal the misery. They speak of measures and silver linings. Things are getting steadily better for them, and steadily worse for us. The illusion of freedom, peace and prosperity that we were promised when we wanted to take our fate in our own hands is vanishing. Only complete collapse of our people can follow from these irresponsible policies.

Thus we demand the right of work and a decent living for every working German.

While the front soldier was fighting in the trenches to defend his fatherland, some Eastern Jewish profiteer robbed him of hearth and home. The Jew lives in the palaces and the proletarian, the front soldier, lives in holes that do not deserve to be called “homes.” That is neither necessary nor unavoidable, but rather an injustice that cries out to the heavens. A government that stands by and does nothing is useless and must vanish, the sooner the better.

Therefore we demand homes for German soldiers and workers. If there is not enough money to build them, drive the foreigners out so that Germans can live on German soil.

Our people is growing, others diminishing. It will mean the end of our history if a cowardly and lazy policy takes from us the posterity that will one day be called to fulfill our historical mission.

Therefore we demand land on which to grow the grain that will feed our children.

While we dreamed and chased strange and unreachable fantasies, others stole our property. Today some say this was an act of God. Not so. Money was transferred from the pockets of the poor to the pockets of the rich. That is cheating, shameless, vile cheating!

A government presides over this misery that in the interests of peace and order one cannot really discuss. We leave it to others to judge whether it represents Germany’s interests or those of our capitalist tormenters.

We however demand a government of national labor, statesmen who are men and whose aim is the creation of a German state.

These days anyone has the right to speak in Germany—the Jew, the Frenchman, the Englishman, the League of Nations, the conscience of the world, and the Devil knows who else. Everyone but the German worker. He has to shut up and work. Every four years he elects a new set of torturers, and everything stays the same. That is unjust and treasonous. We need tolerate it no longer. We have the right to demand that only Germans who build this state may speak, those whose fate is bound to the fate of their fatherland.

Therefore we demand the destruction of the system of exploitation! Up with the German worker’s state!

Germany for the Germans!

Germans who want to read relevant literature in their native language can purchase books here (my humble Daybreak Publications only has one title in German, William Pierce’s Jäger).

Update: Today Richard Spencer and Greg Johnson are fighting over the forums (see e.g., Spencer’s Twitter and Facebook accounts and Johnson’s webzine). Of course: those of us who sympathize with National Socialism don’t take sides in personal disputes between white nationalists. We have more important stuff to read…

by Hans Günther

Editor’s Note: “The Nordic ideal: A result of the anthropological view of history,” is the last chapter of The Racial Elements of European History by Hans Friedrich Karl Günther, translated to English in 1927. Günther was professor of race science in Berlin during the Third Reich.

______ 卐 ______

If degeneration (that is, a heavy increase in inferior hereditary tendencies) and denordization (that is, disappearance of the Nordic blood) have brought the Asiatic and south European peoples of Indo-European speech to their decay and fall, and if degeneration and denordization now, in turn, threaten the decay and fall of the peoples of Germanic speech, then the task is clearly to be seen which must be taken in hand, if there is still enough power of judgment left: the advancement of the peoples of Germanic speech will be brought about through an increase of the valuable and healthy hereditary tendencies, and an increase of the Nordic blood. The works on general eugenics show how the valuable hereditary tendencies can be increased. Here, therefore, we will only deal with the question of the renewal of the Nordic element.

If degeneration (that is, a heavy increase in inferior hereditary tendencies) and denordization (that is, disappearance of the Nordic blood) have brought the Asiatic and south European peoples of Indo-European speech to their decay and fall, and if degeneration and denordization now, in turn, threaten the decay and fall of the peoples of Germanic speech, then the task is clearly to be seen which must be taken in hand, if there is still enough power of judgment left: the advancement of the peoples of Germanic speech will be brought about through an increase of the valuable and healthy hereditary tendencies, and an increase of the Nordic blood. The works on general eugenics show how the valuable hereditary tendencies can be increased. Here, therefore, we will only deal with the question of the renewal of the Nordic element.

The French Count Arthur Gobineau (1816-82), was the first to point out in his work, Essai sur l’inégalité des races humaines (1853-5), the importance of the Nordic race for the life of the peoples. Count Gobineau, too, was the first to see that, through the mixture of the Nordic with other races, the way was being prepared for what today (with Spengler) is called the “Fall of the West”. Gobineau’s personality as investigator and poet (“all the conquering strength of this man”) has been described by Schemann, and it is, thanks to Schemann, through his foundation in 1894 of the Gobineau Society (to further Gobineau’s ideas), and through his translation of the Essay on the Inequality of Human Races, which appeared 1898-1901, that Gobineau’s name and the foundations he traced for the Nordic ideal have not fallen into forgetfulness. The very great importance of Gobineau’s work in the history of the culture of our day is shown by Schemann in his book, Gobineaus Rassenwerk (1910).

It is evident that Gobineau’s work on race, which was carried out before investigations into race had reached any tangible results, is in many of its details no longer tenable today. The basic thought of this work, however, stands secure. From the standpoint of racial science we may express ourselves as to Gobineau’s work in somewhat the same way as Eugen Fischer, the anthropologist: “The racial ideal must and will force its way, if not quite in the form given it by Gobineau, at any rate from the wider point of view quite in his sense; he was the great forerunner.”

The turn of the century, when Schemann’s translation appeared, may be said to be the time from which onwards a certain interest in racial questions was aroused. About the same time, too, in 1899, appeared the work which for the first time brought the racial ideal, and particularly the Nordic ideal, into the consciousness of a very wide circle through the enthusiasm, and also the opposition, which it aroused: this work was The Foundations of the Nineteenth Century, by H. S. Chamberlain (born 1855), at that time an Englishman, now a German. On this work from the standpoint of racial science we may pass a judgment somewhat like that of Eugen Fischer: “Undeterred by the weak foundations of many details, and recklessly changing even well-established conceptions to serve his purpose, he raises a bold structure of thought, which thus naturally offers a thousand points for attack, so that the real core of the matter escapes attack—and it would stand against it.”

Since the works of Gobineau and Chamberlain appeared, many investigators, in the realms of natural and social science, have devoted themselves eagerly to bringing light into racial questions, so that today not only the core of the theory both of Gobineau and of Chamberlain stands secure, but also much new territory has been won for an ideal of the Nordic race. A new standpoint in history, the “racial historical standpoint,” is shaping itself.

The Nordic race ideal naturally meets with most attention among those peoples which today still have a strong strain of Nordic blood, of whom some are even still very predominantly Nordic—that is, among the peoples of Germanic speech in Europe and North America. It is unlikely that Gobineau’s thought will find a home among the peoples of Romance speech, even though the first scientific work from the racial historical standpoint, L’Aryen, son rôle social (which likewise appeared in 1899), has a Frenchman, Georges Vacher de Lapouge, for its author. Denordization has probably already gone too far in France also. Any great attention towards race questions is unlikely, too, among peoples of Slav speech.

But the result was bound to be that in all those peoples who came to know Gobineau’s theory there were some persons who were deeply moved by them. Since the end of last century we can, as was said above, even speak of a growing interest in race questions, although we cannot yet speak of a spread of clear ideas. Following the terms used by Gobineau and Chamberlain, we come here and there upon more or less clear conceptions of the need for keeping the “Germanic” blood pure, or (following Lapouge) of keeping the “Aryan” blood pure. In this way the door is always left wide open to the confusion of race and people or of racial and linguistic membership, and a clear definition of aims is impossible. What was (and still is) lacking is a knowledge of the conception of “race”, and a knowledge of the races making up the Germanic peoples (that is, peoples speaking Germanic tongues) and the Indo-European peoples (that is, peoples speaking Indo- European tongues). There was (and still is) lacking a due consideration of the racial idiotype (hereditary formation) of the Nordic man, as the creator of the values which characterize the culture of the Indo-European (“Aryan”) and the Germanic peoples. A racial anthropology of Europe could not be written in Gobineau’s time. Many detailed investigations were still needed.

But more was (and is still) wanting: Gobineau, like his contemporaries, had as yet no knowledge of the importance of selection for the life of peoples. The Nordic race may go under without having been mixed with other races, if it loses to other races in the competition of the birth-rate, if in the Nordic race the marriage rate is smaller, the marrying age higher, and the births fewer. Besides an insight into the “unique importance of the Nordic race” (Lenz) there must be also a due knowledge of the laws of heredity and the phenomena of selection, and this knowledge is just beginning to have its deeper effect on some of the members of various nations.

Maupertius (1744, 1746) and Kant (1775, 1785, 1790) had been the first to point out the importance of selection for living beings. But the influence of the conception of selection only really begins to show itself after the foundations of modern biology were laid by Darwin’s Origin of Species in 1859. The conception of selection was bound to have an effect on the view taken of the destiny of the peoples. Darwin’s cousin, Francis Galton (1822-1911), the “father of eugenics,” was the first to see this. He was the first to show that it is not environment but heredity which is the decisive factor for all living beings, and therefore for man too, and drew the outlines of a theory of eugenics in the knowledge that the improvement of a people is only possible by a sensible increase of the higher hereditary qualities. But it took nearly forty years for Galton’s importance to be rightly understood and for his work to bear fruit.

Galton’s views had as yet no scientific theory of heredity on which to build. This was created in its main outlines by Johann Mendel (1822-84), an Augustinian father in Brünn (in religion he was known as Gregor), whose life-work, after its recovery in 1900, had so deep an effect that research after research was undertaken, and today a wide-embracing science of heredity stands secure.

Through researches such as these Gobineau’s teachings received a deeper meaning, and found fresh support from all these sources, from the sciences of heredity, eugenics, and race: the Nordic movement was born. It had to come into being in those countries where there was still enough Nordic blood running in the peoples to make a Nordic new birth possible. Thus in Germany societies have been founded aiming at the propagation of the Nordic ideal; thus societies of the same kind have been founded in the United States; and such societies would seem sometimes to go beyond these countries.

If the Nordic ideal in Germany has been active longer than in other countries, it would seem, owing to the splitting up of its followers into small groups, and to put a bar on the unwished-for immigration from south and east Europe. Immigration from Asia, and the immigration of undesirables in general, is forbidden. Grant himself has been chosen as vice-president of the Immigration Restriction League. It may be presumed that the Immigration Laws as now passed are only the first step to still more definite laws dealing with race and eugenics. In North America, especially, where there is the opportunity to examine the races and racial mixtures of Europe from the point of view of their civic worth, the importance of the Nordic race could not stay hidden. Leading statesmen have seen the importance of this race, and are proclaiming their knowledge. In North America a significant change is taking place in our own day: Europe as an area of emigration is no longer looked at in the light of its states or peoples, but in the light of its races. How Germany (or the pick of German emigrants) in this regard strikes America, may be seen from the fact that Germany, as a land of emigrants, is the most highly favoured of all European countries.

The peril of denordization (Finis Americae, Grant) has been recognized by many Americans since Grant’s book appeared. Associations have been formed among the Nordic and predominantly Nordic Americans of Anglo-Saxon descent, such as “The Nordic Guard,” and among Americans of German descent (“The Nordic Aryan Federation,” and so on). Some of the Nordic-minded North Americans seem to have joined together in co-operative unions, so as to make themselves gradually economically independent of big capital in non-Nordic hands. It would seem as though the Nordic-minded sections of North America had begun with great forethought and efficiency to take steps for the maintenance and increase of Nordic blood. A better insight, however, is perhaps still needed into the importance of the birth-rate for all such aims.

When it is remembered that the Nordic ideal in Germany had taken root here and there as long ago as the end of last century, we do not get, on the whole, from the Nordic strivings of this country that picture of unity and purpose which is shown by North America. However, we must not overlook the economically very straitened circumstances in which the German followers of the Nordic ideal, who in greatest part belong to the middle classes, find themselves—circumstances which are always piling up hindrances to any forward striving. The hindrances, however, in the path of a Nordic movement lie partly in the German nature itself, in the splitting up into small exclusive groups each with its own “standpoint,” which is found over and over again. This splitting up is the reason why the “societies for the defence of the Nordic race” (Ploetz) in Germany can only be looked on as the beginning of an interest in race questions, and why we must agree with Ploetz when he speaks of these “defensive societies” as being “considerably poorer in membership and influence than those of the Jews”; indeed, we cannot yet speak of any “influence” of the Nordic ideal.

These endeavours along Nordic lines, however, are not to be undervalued as tokens of an awakening attention to race questions. Those among the youth who have been gripped by the Nordic ideal have already done much to spread their views, even under the crushing conditions of today in Germany, and in spite of the lack of money. The beginnings may be humble, but the deep change is full of importance; “Individualism,” so highly prized in the nineteenth century, and still loudly proclaimed by yesterday’s generation, is coming to an end. The stress laid on each man’s individuality, which up till yesterday was proclaimed with the resounding shout of “Be thyself,” has become a matter of doubt, even of contempt, to a newer generation. It set me pondering, when, during the writing of this book, the statement of the aims of a “Young Nordic Association” reached me, in which I find the following sentence: “We wish to keep the thought always before us that, if our race is not to perish, it is a question not only of choosing a Nordic mate, but over and above this, of helping our race through our marriage to a victorious birth-rate.”

Up to the other day such a view of life would not have met with any understanding, and to yesterday’s generation it must still seem beyond comprehension. The present age, indeed, was brought up amidst the ideas of the “natural equality of all men,” and of the distinct individuality of each one of us (“Individualism,” “Cultivation of personality”). When we look back today, we are astonished to see how long the biologically untenable theories of the Age of Enlightenment and of Rousseau (1712-78) could hold the field, and how, even today, they determine the attitude towards life of great masses of men, although men like Fichte and Carlyle had already gone beyond such views. Although really discredited, the ideas of equality and individualism still hold the field, since they satisfy the impulses of an age of advanced degeneration and denordization, or at least hold out hopes of doing so, and yield a good profit to those exploiting this age. If, without giving any heed to the definitions of current political theories, we investigate quite empirically what is the prevailing idea among the Western peoples of the essential nature of a nation, we shall find that by a nation no more is generally understood than the sum of the now living citizens of a given State. We shall find, further, that the purpose of the State is generally held to be no more than the satisfaction of the daily needs of this sum of individuals, or else only of the sum of individuals who are banded together to make up a majority. The greatest possible amount of “happiness” for individuals is to be won by majority decisions.

Racial and eugenic insight brings a different idea of the true nature of a people. A people is then looked upon as a fellowship with a common destiny of the past, the living, and the coming generations—a fellowship with one destiny, rooted in responsibility towards the nation’s past, and looking towards its responsibility to the nation’s future, to the coming generations. The generation living at any time within such a people is seen by the Nordic ideal as a fellowship of aims, which strives for an ever purer presentment of the Nordic nature in this people. It is thus only that the individual takes a directive share in the national life through his active responsibility. But in this fellowship of aims it is the predominantly Nordic men who have the heaviest duties: “O, my brothers, I dedicate and appoint you to a new nobility: ye shall become my shapers and begetters, and sowers of the future” (Nietzsche, Also sprach Zarathustra).

The striving that can be seen among the youth for an “organic” philosophy of life—that is, a philosophy sprung from the people and the native land, bound up with the laws of life, and opposed to all “individualism”—must in the end bind this youth to the life of the homeland and of its people, just as the German felt himself bound in early times, to whom the clan tie was the very core of his life. It could be shown that the old German view of life was so in harmony with the laws of life that it was bound to increase the racial and eugenic qualities of the Germans, and that, with the disappearance of this view of life in the Middle Ages, both the race and the inheritance of health were bound to be endangered. And a Nordic movement will always seek models for its spiritual guidance in the old Germanic world, which was an unsullied expression of the Nordic nature.

In the nations of Germanic speech the Nordic ideal still links always with popular traditions handed down from Germanic forbears whose Nordic appearance and nature is still within the knowledge of many. Unexplained beliefs, unconscious racial insight, are always showing themselves; this is seen in the fact that in Germany a tall, fair, blue-eyed person is felt to be a “true German,” and in the fact that the public adoption offices in Germany are asked by childless couples wishing to adopt children far oftener for fair, blue-eyed, than for dark ones. The Nordic ideal as the conception of an aim has no difficulty in taking root within the peoples of Germanic speech, for in these peoples the attributes of the healthy, capable, and high-minded, and of the handsome man, are more or less consciously still summed up in the Nordic figure. Thus the Nordic ideal becomes an ideal of unity: that which is common to all the divisions of the German people—although they may have strains of other races, and so differ from one another—is the Nordic strain. What is common to northern and to southern England—although the south may show a stronger Mediterranean strain—is the Nordic strain. It is to be particularly noted that in the parts of the German-speaking area which are on the whole predominantly Dinaric, and in Austria, too, the Nordic ideal has taken root, and unions of predominantly Nordic men have been formed.

Thus a hope opens out for some union among the peoples of Germanic speech; what is common to these peoples, although they may show strains of various races, is the Nordic strain. If the Nordic ideal takes root within them, it must necessarily come to be an ideal of harmony and peace. Nothing could be a better foundation and bulwark of peace among the leading peoples than the awakening of the racial consciousness of the peoples of Germanic speech. During the Great War Grant had written that this was essentially a civil war, and had compared this war in its racially destructive effects to the Peloponnesian War between the two leading Hellenic tribes. The Nordic-minded men within the peoples of Germanic speech must strive after such an influence on the governments and public opinion, that a war which has so destroyed the stock of Nordic blood as the Great War has done shall never again be possible, nor a war in the future into which the nations are dragged in the way described by Morhardt, the former president of the French League for the Rights of Man, in his book, Les preuves (Paris, 1925). The Nordic ideal must widen out into the All-Nordic ideal; and in its objects and nature the All-Nordic ideal would necessarily be at the same time the ideal of the sacredness of peace among the peoples of Germanic speech.

In the war of today, and still more in that of tomorrow, there can no longer be any thought of a “prize of victory” which could outweigh the contra-selection necessarily bound up with any war. For any one who has come to see this, it seems very doubtful whether even the most favourable political result of a contest deserves to be called a “victory,” if the fruits of this “victory” fall to those elements of a nation who, as a result of their hereditary qualities, have slipped through the meshes of the modern war-sieve. The real victims in any future war between the Great Powers, whether in the losing or in the “winning” nation, are the hereditary classes standing out by their capacity in war and spirit of sacrifice. It will be one of the tasks of the followers of the Nordic ideal to bring this home to their peoples and governments.

If this prospect of a political influence wielded by the Nordic ideal seems today a very bold forecast, yet the task of bringing about a Nordic revival seems to arise very obviously from the history of the (Indo-European) peoples under Nordic leadership, as the most natural ideal to set against the “decline” which today is also threatening the peoples of Germanic speech. There is no objection against the Nordic ideal which can be given any weight in the face of a situation which Eugen Fischer (in 1910) described as follows for the German people: “Today in Italy, Spain, and Portugal, the Germanic blood, the Nordic race, has already disappeared. Decline, in part insignificance, is the result. France is the next nation that will feel the truth of this; and then it will be our turn, without any doubt whatever, if things go on as they have gone and are going today.” And since this utterance there has been the dreadful contra-selection of the Great War.

This being the situation, the problem is how to put a stop to denordization, and how to find means to bring about a Nordic revival. How are Nordics and those partly Nordic to attain to earlier marriages and larger families?—that is the question from the physical side of life. How is the spirit of responsibility, of efficiency, and of devotion to racial aims to be aroused in a world of selfishness, of degeneration, and of unbounded “individualism”?—that is the question from the spiritual side of life.

Once this question is seen by thoughtful men in the peoples of Germanic speech to be the one vital question for these peoples, then they will have to strive to implant in the predominantly Nordic people of all classes a spirit of racial responsibility, and to summon their whole nation to a community of aims. An age of unlimited racial mixture has left the men of the present day physically and mentally rudderless, and thus powerless for any clear decision. There is no longer any ideal of physical beauty and spiritual strength to make that bracing call on the living energies which fell to the lot of earlier times. If selection within a people cannot be directed towards an ideal, unconsciously or consciously pursued, then its power to raise to a higher level grows weaker and weaker, and it ends by changing its direction, turning its action towards the less creative races, and the inferior hereditary tendencies. Every people has had assigned to it a particular direction of development, its own special path of selective advance. The selective advance in the peoples of Germanic speech can have as its goal only the physical and spiritual picture presented by the Nordic race. In this sense the Nordic race is (to use Kant’s expression) not given as a gift but as a task; and in this sense it was that, in speaking of “the Nordic ideal among the Germans,” we necessarily spoke of the Nordic man as the model for the working of selection in the German people, and showed that no less a task is laid on the Nordic movement than the revival of a whole culture.

The question is not so much whether we men now living are more or less Nordic; but the question put to us is whether we have courage enough to make ready for future generations a world cleansing itself racially and eugenically. When any people of Indo- European speech has been denordicized, the process has always gone on for centuries; the will of Nordic-minded men must boldly span the centuries. Where selection is in question, it is many generations that must be taken into the reckoning, and the Nordic-minded men of the present can only expect one reward in their lifetime for their striving: the consciousness of their courage. Race theory and investigations on heredity call forth and give strength to a New Nobility: the youth, that is, with lofty aims in all ranks which, urged on like Faust, seeks to set its will towards a goal which calls to it from far beyond the individual life.

Since within such a movement profit and gain is not to be looked for, it will always be the movement of a minority. But the spirit of any age has always been formed by minorities only, and so, too, the spirit of that age of the masses in which we live. The Nordic movement in the end seeks to determine the spirit of the age, and more than this spirit, from out of itself. If it did not securely hold this confident hope, there would be no meaning or purpose in any longer thinking the thoughts of Gobineau.