by Ragnar Redbeard [1]

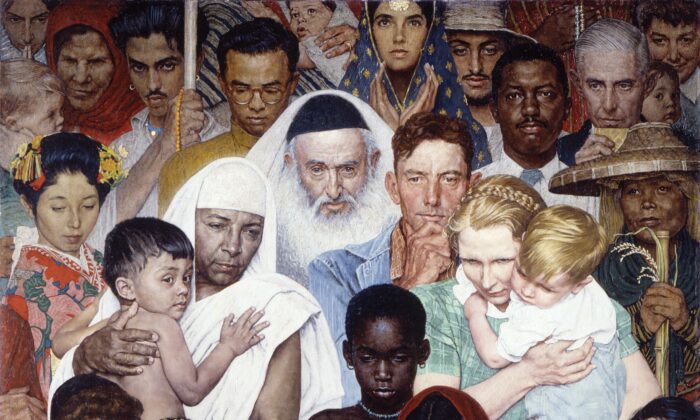

The Golden Rule by Norman Rockwell (oil on canvas). Fifteen years after WW2, The Saturday Evening Post relaxed its stance on the depictions of races other than white people. One of the first multiracial images to grace the cover of the Post was Rockwell’s The Golden Rule.

Is the Golden Rule a rational rule? — Is it not rather a menial rule — a coward rule — a best-policy rule? Why is it ‘right’ for one man to do unto others as he would have others do to him and, what is right? If ‘others’ are unable to injure him or ‘do good’ to him, why should he consider them at all? Why should he take any more notice of them than of so many worms? If they are endeavouring to injure him, and able to do it, why should he refrain from returning the compliment? Should he not combat them, does not that give them carte-blanche to injure and destroy him? May it not be ‘doing good’ to others, to war against them, to annihilate them? May it not also be ‘good’ for them to war against others? (Again, what is ‘good’?)

Is it reasonable to ask preying animals, to do unto others as they would be done by? — If they acted accordingly would they, could they survive? If some only accepted the Golden Rule as their guiding moral maxim, would they not become a prey to those who refused to abide thereby?

Upon what reasonable and abiding sanction does this ‘Rule’ rest? — Has it ever been in actual operation among men? — Can it ever be successfully practiced on earth — or anywhere else? — Did Jesus Christ practice it himself upon all occasions? — Did His apostles, his ‘sons of thunder’ practice it? — Did Peter the boaster do so, when he ‘denied Him’ for fear of arrest at the camp-fire? — Did Judas the financier, when he sold him for net cash? Also, how many of his modern lip-servants actually practice it in their daily business intercourse with each other? How Many?

These questions require no formal answering. They answer themselves in the asking. And here it must be remembered that the best test of a witness, is cross-examination. ‘Do unto others as you would have others do to you.’ No baser precept ever fell from the lips of a feeble Jew.

It is from alleged moralisms of this sort, and fabulous ‘principles’ that our mob orators, our communards, revivalists, anarchists, red-republicans, democrats, and other mob-worshippers in general derive the infernal inspiration that they are perpetually hissing forth. Even the subversive pyrotechnic watchwords of their mephisto-millennium, are to be found in the ‘holy gospels.’ Is it not written, ‘and God sendeth angels to destroy the people?’ — Behold! these men are the ‘angels’ that He sends: — politicians and reformers!

‘Love one another’ you say is the supreme law, but what power made it so? — Upon what rational authority does the Gospel of Love rest? — Is it even possible to practice, and what would result from its universal application to active affairs? Why should I not hate mine enemies, and hunt them down like the wild beasts that they are? Again I ask, why? If I ‘love’ them does that not place me at their mercy? Is it natural for enemies to ‘do good’ unto each other and, what is ‘good’? Can the torn and bloody victim ‘love’ the blood-splashed jaws that rend it limb from limb? Are we not all predatory animals by instinct? If humans ceased wholly from preying upon each other, could they continue to exist?

‘Love your enemies and do good to them that hate you and despitefully use you,’ is the despicable philosophy of the spaniel that rolls upon its back, when kicked. Obey it, O! reader, and you and all your posterity to the tenth generation shall be irretrievably and literally damned. They shall be hewers of wood, and carriers of water, degenerates, Gibeonites. But hate your enemies with a whole heart, and if a man smite you on one cheek, smash him down; smite him hip and thigh, for self-preservation is the highest law.

He who turns the ‘other cheek’ is a cowardly dog — a Christian dog.

Give blow for blow, scorn for scorn, doom for doom, with compound interest liberally added thereunto. Eye for eye, tooth for tooth, aye four-fold, a hundredfold. Make yourself a Terror to your adversary and when he goeth his way, he will possess much additional wisdom to ruminate over. Thus shall you make yourself respected in all the walks of life, and your spirit — your immortal spirit — shall live, not in an intangible paradise, but in the brains and thews of your aggressive and unconquerable sons. After all, the true proof of manhood is a splendid progeny; and it is a scientific axiom that the timid animal transmits timidity to its descendents.

If men lived ‘like brothers’ and had no powerful enemies (neighbors) to contend with and surpass, they would rapidly lose all their best qualities; like certain oceanic birds that lose the use of their wings, because they do not have to fly from pursuing beasts of prey. If all men had treated each other with brotherly love since the beginning, what would have been the result now? If there had been no wars, no rivalry, no competition, no kingship, no slavery, no survival of the Toughest, no racial extermination, truly what a festering ‘hell fenced in’ this old globe would be?

_____________

[1] According to Wikipedia it was Arthur Desmond (1859-1929) who wrote under the pen name ‘Ragnar Redbeard’.