by Gaedhal

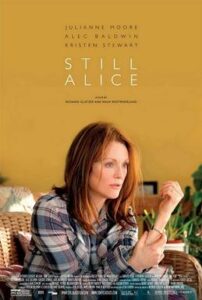

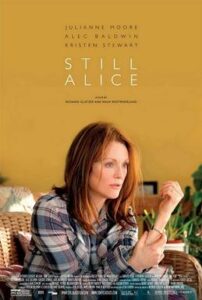

I watched the 2014 film, Still Alice, yesterday.

I watched the 2014 film, Still Alice, yesterday.

One of the things that I liked about it was its treatment of the stages of grief. The denial stage is well treated. Alec Baldwin just openly denies that Alice has Alzheimer’s. Alice is quick, almost immediate, to acknowledge verbally that she has Alzheimer’s, but she still lives in denial. She still believes that she can go running, go on holiday, lecture Linguistics at college etc. And also, we kinda get a subtle hint from a neurologist who looks uncannily like Lawrence Krauss that Alice was late in seeking a diagnosis. It was only really when Alice could no longer disguise her memory problems that she sought a diagnosis.

Alice has familial early-onset Alzheimer’s. This is caused by a mutation in the genome.

I remember, in the grand old days of yore, I used to install television satellite dishes with my father. The set-top box, for to decode and unencrypt the digital television signal had a forward error correction rate. The set top box had an algorithm that could correct some errors received from the Satellite. Do not ask me about the engineering wizardry behind this. To me, digital satellite television is a technology sufficiently advanced to be indistinguishable from magic.

However, where is the forward error correction in our genome? Unintelligent design strikes again. This is why, in my view, Paley’s watchmaker argument fails in our day. In Paley’s day, technology was still, very much, in a crude and primitive state. However, in our day, the process of technological manufacturing is so refined that the organs—organum in Latin means: ‘tool’ or ‘instrument’—produced by nature are wholly deficient when compared to the tools, and instruments produced by humans. We humans can contrive forward error correction, whereas biology and nature, thus far, cannot.

And this, incidentally, is why I am pro-abortion.

One of Alice’s children has the gene for early-onset Alzheimers. She swiftly conceives twins by IVF. The embryos in the petri dish are screened for the familial-Alzheimer’s disease, and the embryos containing this gene are destroyed, and only the healthy embryos are implanted. In essence, a woman’s uterus does the same thing: it screens sperm and embryos for nasty genetic material, and if it discovers any such nasty genetic material, then it either kills the sperm, or it kills the embryo or foetus. Thus, naturally, a woman’s uterus has its own contraception and abortion mechanisms. Contraception and abortion is merely the augmentation of a natural process. And if you believe in God, then God ultimately designed these contraceptive and abortifacient faculties that a woman contains in her uterus.

Evolution explains this. Evolution wants a woman to give birth to offspring that will reach adulthood, such that they too will either give birth to or sire offspring. Evolution does not want a woman to either accept defective sperm or to incubate defective embryos. Thus, evolutionarily speaking, the contraceptive and abortifacient faculties that a woman already possesses makes sense. And if you want to defy Ockham’s razor and add a god to the mix, then go ahead. If you do so, then contraception and abortion become divine.

Anyhow, another pro-death position that I hold is euthanasia. There is a scene where Alice tries to commit suicide by ingesting an overdose of Rohypnol. I, of course, was cheering her on, because Alzheimer’s is a fate worse than death. At this point of the film, she was only ½ Alice, by my reckoning. Unfortunately, Consuela from Family Guy, her nurse and housekeeper, gives her a jump-scare, knocking the tablets out of her hand, dooming her to become a human vegetable.

If I ever get diagnosed with dementia, I will book a trip to Switzerland and ingest some Pentobarbital at a Dignitas facility. However, such a service, ideally, ought to be available in Ireland. Evangelical Protestantism prevents euthanasia from being a reality in the North—although it is becoming a reality on the British mainland—and the vestiges of a Catholic theocracy prevent euthanasia from becoming a reality in the South. Again, why I am an antitheist. On the Island of Ireland, Roman Catholicism and Calvinism—the two biggest brands of Christianity, on this island—still have way, way, way too much power. There are no good secular arguments against euthanasia, just as there are no good secular arguments against abortion. Which is why the atheist British mainland is far in advance of Ireland, North and South on these issues.

My grandmother was not still my grandmother after about a year and a half of dementia. However, she lived on as a human potted plant—a mockery of her former form—for about two years after. I was glad, for her sake, when she died. In the words of Saint Thomas More, in his Utopia she outlived herself. Annie Bessant quotes the Utopia in her essay in favour of euthanasia.

______ 卐 ______

Editor’s 2 ¢

Since I studied the fraudulent profession called psychiatry in-depth, I realised, in reviewing its 19th-century origins, that psychiatrists were simply pathologizing behaviour such as suicide, a ‘sin’ considered lèse majesté divine, dogmatically declaring it to be a disease of unknown biomedical aetiology (and the same with the other diagnostic categories ‘of unknown aetiology’!).

Like me, Benjamin has spotted a tremendous error in the racial right, for example, in the comments sections where hundreds of commenters opine in The Unz Review. None of them seem to notice the pseudo-scientificity of psychiatry. Neochristianity, as we understand it on this site, means that the axiological tail of Christian morality persists, foolishly, in today’s secular world. What Gaedhal mentions above is only one example.

I would add that the negrolatry (BLM, mixed couples, etc.) that so afflicts today’s mad West is another example of Christian morality exponentially exacerbated in the secular world (from this site’s seminal essay, ‘The Red Giant’, a Swede noted that secularism exacerbates Christian morality big time).

White nationalists shouldn’t ignore us. They should realise that rather than our paradigm (CQ) competing with theirs (JQ), our POV expands the latter as with the iceberg metaphor. They only see the iceberg’s tip but we know that the Jewish Problem is supported by the huge mass of Christian ethics that lies underneath. Dr Robert Morgan agrees with us in the post from a couple of days ago.