In my first new contact with Europe, after the disaster of 1945, I wrote to a Hindu correspondent, after quoting Nietzsche’s phrase on the intermediate character of man, ‘a rope stretched between animality and superhumanity’. ‘The rope is now broken. There are no more men on this godforsaken continent; there is only a superhuman minority of true Hitlerians, and… an immense majority of apes’.

______ 卐 ______

Editor’s Note: What I call ‘the Neanderthals’.

______ 卐 ______

Such then was the contrast between the dazzling elite of the faithful, whom I exalted in the first of my post-war books[1]: ‘those men of gold and steel, whom defeat cannot deter, whom terror and torture cannot break, whom money cannot buy’—and the rest of the Europeans.

Since then, I have seen this precious minority gradually renew itself, while remaining profoundly the same—like the waters of a lake fed by a river. Many of the Alten Kämpfer (old militants) of the glorious years have died, and more than grew weary of waiting for the impossible return of the dawn—or of what they had so long taken to be ‘a dawn’—of the Aryan renaissance, and, without having died in the flesh, have sunk into the apathy of those who no longer hope, even though hope was indispensable to them. Only the Strong remained who had no use for hope because, while contributing through their activity (and by the magical fervour of their thought, when all action is forbidden to them) to the immemorial struggle against the Powers of disintegration, they have transcended Time. Only those who do not need to ‘believe’, because they know, are left standing.

And around these few survivors of the wreckage of the most beautiful of races, I have seen, in the course of this quarter of a century, a hard and silent elite of young people grouping—consciously known to each of them or not, it does not matter—an elite very few in number, no doubt, but oh joy! of a quality which the vast hostile world doesn’t suspect (and which it could not alter even if, one day, it suddenly imposed itself upon it). I have seen growing here and there, outside of what may seem to the historian our definitive ruin, the miraculous fruits of the unparalleled ordeal of boys and girls of twenty strong enough, already, to do without hope as well as success; intelligent enough to understand once and for all that Truth does not depend on the visible.

One of them[2] said to me in 1956, and others have repeated to me more than ten years later: ‘I oppose and will continue all my life to oppose the current of decadence, convinced as I am of the eternity of the Hitlerian ideal, although I know that we will not see, until the end of time, the equivalent of the Third German Reich. We must fight ceaselessly and without fail, even knowing in advance that we are overwhelmed; one must fight, because this is the duty—the function—of the Aryan of our time, and of all times to come’.

I then thought of Goebbels’ words uttered amidst all the horror of the disaster: ‘After the flood, us!’ Was it the nature of this disaster to bring forth to the continent for which the false civilisation is destined—and how precisely!—to be swept away, a few young people (mostly Germans, but not necessarily) whose spontaneous mentality, corresponding exactly to the teachings of the Bhagawad-Gita, matches that of the very prototype of the Arya of old? And was the resurrection, in our time, of the ethic of imperturbable serenity within untiring action—the wisdom of the Divine Warrior—to be the result of the Passion of Germany?

Perhaps. If so, it was worth surviving the disaster to witness this resurrection. It was worth wandering from year to year among all the apes of the ‘consumer societies’ to make sure, finally, that the spirit of the Leader and the Master would not disappear with the death of the last of the militants of the old guard, but would continue to animate, in its hardness and its purity, a spiritual as well as racial aristocracy, which had not been born in 1945.

This spiritual as well as racial aristocracy—this elite, conscious of the eternity of the basic principles of Adolf Hitler’s doctrine, and living according to them in all simplicity—is, for us, the true ‘man’: the man who strives for superhumanity through personal and collective discipline, through the selection of blood, through the cultivation of ancestral honour and divine indifference to all that is not essential; through the humility of the individual before the Race and before the eternity it reflects; through the contempt for all cowardice, all lies and all weakness.

And I repeat: if we find any of these characteristics elsewhere than in those who openly or secretly confess the same doctrine as we do; if we even find it in people who fight us and hate us, or think they hate us because they don’t know us, we salute, in those who have them, beings worthy of respect. They have in them the stuff of what they could and should be, but they don’t use it or misuse it. They are, in most cases, our own brothers of the race, or men of other races, among the most gifted. Something in them redeems them before the immanent and impersonal Justice which sends every being who, rightly or wrongly, professes to think, where he deserves to go, and which has hitherto prevented them—and will always prevent many of them—from slipping and sinking into that mass which neither feels nor thinks according to its law; the simian majority of mankind, which, like liquids or pasty substances, takes on the shape of the vessels that contain it, or the mark of the seal that has, once and for all, struck it.

During this quarter of a century, I have gradually rediscovered this category of people whom my atrocious shock with post-war Europe had at first withdrawn from my attention: the men of goodwill, the good people who keep their word and are capable of a good deed that brings them no profit; who, for example, would go out of their way to rescue an animal without, however, being capable of extreme sacrifice, even of sustained, daily, total action for the benefit of anyone.

They are not the Strong, and certainly not us. But they are not apes. In an intelligent sorting, they should be spared. Among their children, there could be future militants of Hitlerism—as their opposite. A reading, a conversation at the crucial moment, a small thing, can decide the evolution of each of them. One must be careful: not to despise what is healthy, but not to waste one’s time and energy in trying to hold back on the slope what, in any case, is predestined—condemned by nature—to sink into the mass of non-thinkers; a mass that is sometimes usable but never respectable and a fortiori never likeable.

He is not ‘man’ in the sense that we understand it, man, a valid candidate for true superhumanity; nor is he the ‘good man’, sound in body and soul, fundamentally honest and kind, well disposed towards all that lives, whom we ‘deny’. In other words, it is not to him that we deny more ‘dignity’ and hence more consideration than a simple thing; not to him, but to this caricature of man, increasingly common in the world in which we live. It is this that we refuse to include in the denotation of the concept of ‘man’, for the simple reason that it does not have the connotation, that is to say, it does not possess the essential qualities and capacities that quite naturally serve as attributes in possible judgements where the word ‘man’ is used as a subject.

Any judgment in which a concept is used as a subject is necessarily a hypothetical judgment. To say that ‘man thinks’, or that he is a ‘thinking being’, is to say that if any individual is ‘a man’—if he possesses upright posture, speech—it follows that he is also capable of thinking. In case he is not able to do so, the upright posture and the articulate word, and the other features which accompany these, are insufficient to define him—and do not oblige anyone to treat him as ‘a man’.

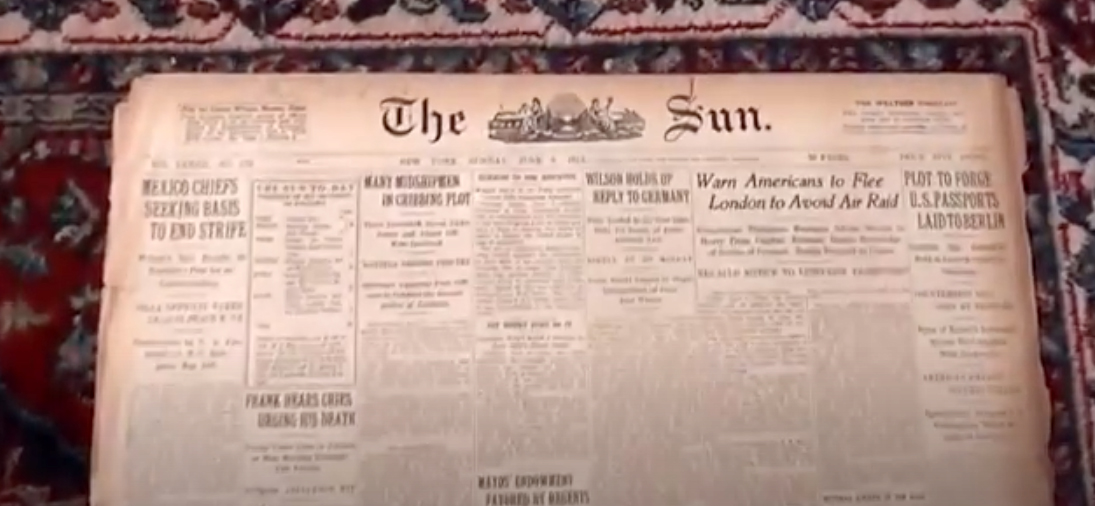

Now, a person does not think if he tells you, in all seriousness, that a piece of information is ‘certainly correct’ because it was transmitted to him by his television set, or especially that a value judgement must ‘certainly’ be accepted because he has read the statement in a newspaper, magazine book, or on a poster, wherever it is printed. It does not ‘think’ any more than does a gramophone whose needle faithfully follows record grooves. Change the record, and the machine will change its language or its music.

In the same way, change the television broadcasts, which millions of families watch every night with ear and eye; change the radio programs; pay the press to print other propaganda, and encourage the publication of other magazines and books, and in three months you will change the reactions of a people—of all peoples—to the same events, to the same political or literary figures, to the same ideas. Why, great Gods, should we treat as ‘men’ those millions of gramophones of flesh and blood who do not ‘think’ any more than their metal and Bakelite colleagues?

The latter cannot think, and it would be absurd to ask them to. They have neither brains nor nerves. They are objects. The individual—the two-legged mammal—who comes to me and insists that ‘six million’ Jews, men, women and children, died in the gas chambers of the German concentration camps, and who gets angry if I show him that this number has one (or perhaps two) extra zeros, is worse than an object.

______ 卐 ______

Editor’s Note: Today the internet exists, and we can see images that from 1915 to 1938 (before the so-called Jewish holocaust began), the Jewish press was already talking about 6 million dead Jews!

Editor’s Note: Today the internet exists, and we can see images that from 1915 to 1938 (before the so-called Jewish holocaust began), the Jewish press was already talking about 6 million dead Jews!

______ 卐 ______

He has a brain, but does not use it, or uses it only to dumb himself down more and more, refusing any opportunity to exercise what little critical thinking he still possesses after more than forty years of anti-Hitler conditioning. This kind of propaganda started already before 1933: between 1920 and 1930. I was in Europe then and remember it—and how!

Moreover, he dares to find in others, or in the men of old, blind faith, absolute trust in a teaching or a teacher. He blames (or mocks) the people of the Middle Ages for believing without question everything the Church told them and everything written in the Gospels, as if the authority of the Church and the Gospels were not equal to that of television or the magazine. He refuses to admit, because the propaganda he has ingested has told him otherwise, that we are not and have never been ‘conditioned’—at least, those of us who count.

Why, then, should I give him more ‘respect’ than to an object—especially since, precisely because of his nearly perfect indoctrination, he has become for me, for the cause I serve, totally useless? What if, moreover, he is not even good?—if I know, having seen him in action, that he would not hesitate to tear off a tree branch that is in his way, or to throw a stone at a dog? Why—in the name of what—should I feel obliged to prefer him to the dog he once injured, or the tree he mutilated in passing? In the name of his ‘human dignity’?

What dignity is that of a living, evil, dangerous gramophone, capable of inflicting gratuitous suffering and creating ugliness! I deny this ‘dignity’ there. Should I love him ‘because he is my brother’? The tree and the dog and all living beings, beautiful and innocent, who at least have no ideas, neither their own nor those of television, are my brothers. I do not, in any way, sense that this individual is more my brother than any of them. Why should I give him priority over them? Because he walks, like me, on his hind legs?

I don’t think that’s a good reason. I don’t care about standing upright when it doesn’t go hand in hand with real thought and a superior man’s character: a character from which all meanness, all smallness is excluded. And when the articulated word serves only to express ideas which had not been created by the one who thinks he has them, but merely received them—and false ideas to boot—, I prefer, by far, the silence of animals and trees.

______ 卐 ______

Editor’s Note: I find it impressive that what Savitri wrote when I was a child resonates so strongly with my own philosophy. That’s why I am now calling myself a priest and Savitri a priestess…

__________

[1] Gold in the Furnace, written in 1948-1949.

[2] Uwe G., born on 21 July 1935.