(excerpts)

by Richard Weikart

Many Christian leaders in the 1930s and 1940s, both within and outside Germany, recognized Hitler was no friend to their religion. In 1936, Karl Spiecker, a German Catholic living in exile in France, detailed the Nazi fight against Christianity in his book Hitler gegen Christus (Hitler against Christ). The Swedish Lutheran bishop Nathan Soderblom, a leading figure in the early twentieth-century ecumenical movement, was not so ecumenical that he included Hitler in the ranks of Christianity. After meeting with Hitler sometime in the mid-1930s, he stated, “As far as Christianity is concerned, this man is chemically pure from it.”

Many Germans, however, had quite a different image of their Führer. Aside from those who saw him as a Messiah worthy of veneration and maybe even worship, many regarded him as a faithful Christian. Rumors circulated widely in Nazi Germany that Hitler carried a New Testament in his vest pocket, or that he read daily a Protestant devotional booklet. Though these rumors were false, at the time many Germans believed them…

Most historians today agree that Hitler was not a Christian in any meaningful sense. Neil Gregor, for instance, warns that Hitler’s “superficial deployment of elements of Christian discourse” should not mislead people to think that Hitler shared the views of “established religion.” Michael Burleigh argues that Nazism was anticlerical and despised Christianity. He recognizes that Hitler was not an atheist, but “Hitler’s God was not the Christian God, as conventionally understood.” In his withering but sober analysis of the complicity of the Christian churches in Nazi Germany, Robert Ericksen depicts Hitler as duplicitous when he presented himself publicly as a Christian…

However, when we turn to Hitler’s view of Jesus, we find a remarkable consistency from his earliest speeches to his latest Table Talks. He expressed admiration for Jesus publicly and privately, without once directly criticizing Him. But his vision of Jesus was radically different from the teachings of the Catholic Church he grew up in. For him, Jesus was not a Jew, but a fellow Aryan. He only rarely stated this explicitly, though he frequently implied it by portraying Jesus as an anti-Semite. However, in April 1921, he told a crowd in Rosenheim that he could not imagine Christ as anything other than blond-haired and blue-eyed, making clear that he considered Jesus an Aryan. In an interview with a journalist in November 1922, he actually claimed Jesus was Germanic…

While Hitler appreciated Jesus because he considered him a valiant anti-materialistic anti-Semite, I have never found any evidence that Hitler believed in the deity of Jesus. Richard Steigmann-Gall bases his mistaken claim that Hitler believed in Jesus as God on a mistranslation of Hitler’s April 22, 1922 speech (some of which we discussed earlier in this chapter). According to the Norman Baynes’ edition of The Speeches of Adolf Hitler, during that speech Hitler stated about Jesus, “It points me to the man who once in loneliness, surrounded only by a few followers, recognized these Jews for what they were and summoned men to the fight against them and who, God’s truth! was greatest not as sufferer but as fighter.” The term that is translated “God’s truth!” is wahrhaftiger Gott, a common German interjection that is rendered in some German-English dictionaries as “good God!” or “good heavens!” In the original German edition, wahrhaftiger Gott is set off in commas, indicating that it is indeed an interjection… Steigmann-Gall uses this mistranslation to argue that Hitler believed in the deity of Jesus. Apparently, he did not understand the colloquial expression used…

While Hitler’s positive attitude toward Jesus—at least the Jesus of his imagination—did not seem to change over his career, his position vis-a-vis Christianity is much more complex. Many scholars doubt that as an adult he was ever personally committed to any form of Christianity. They interpret his pro-Christian utterances as nothing more than the cynical ploy of a crafty politician. Almost all historians, including Steigmann-Gall, admit that Hitler was anti-Christian in the last several years of his life…

Even when he publicly announced his Christian faith in 1922 or at other times, Hitler never professed commitment to Catholicism. Further, despite his public stance upholding Christianity before 1924, he provided a clue in one of his earliest speeches that he was already antagonistic toward Christianity. In August 1920, Hitler viciously attacked the Jews in his speech, “Why Are We Anti-Semites?” One accusation he leveled was that the Jews had used Christianity to destroy the Roman Empire. He then claimed Christianity was spread primarily by Jews. Since Hitler was a radical anti-Semite, his characterization of Christianity as a Jewish plot was about as harsh an indictment as he could bring against Christianity. Hitler was also a great admirer of the ancient Greeks and Romans, whom he considered fellow Aryans. Blaming Christianity for ruining the Roman Empire thus expressed considerable anti-Christian animus. Hitler often discussed both themes—Christianity as Jewish, and Christianity as the cause of Rome’s downfall—later in life.

Hitler’s anti-Christian outlook remained largely submerged before 1924, because—as Hitler himself explained in Mein Kampf—he did not want to offend possible supporters…

But by the time Hitler wrote Mein Kampf in 1924-25, he was walking a tightrope. His political ally, General Ludendorff, was increasingly hostile to the Catholic Church, as were many on the radical Right in Weimar Germany. Hitler did not want to follow them into political oblivion—and indeed Ludendorff did end up politically isolated, perhaps in part because of his antireligious crusade. But Hitler was also sensitive to the anticlerical thrust within and outside his party. Thus, after warning his followers in the first volume of Mein Kampf against offending people’s religious tastes, he threw caution to the wind in the second volume by sharply criticizing Christianity. In one passage, he complained that both Christian churches in Germany were contributing to the decline of the German people, because they supported a system that allowed those with hereditary diseases to procreate. The problem, he thought, was that the churches focused on the spirit and neglected the physical basis of a healthy life. Hitler immediately followed up this critique by blasting the churches for carrying out mission work among black Africans, who are “healthy, though primitive and inferior, human beings,” whom the missionaries turn into “a rotten brood of bastards.” In this passage, Hitler harshly castigated Christianity for not supporting his eugenics and racial ideology.

Worse yet, he actually threatened to obliterate Christianity later in the second volume. After calling Christianity fanatically intolerant for destroying other religions, Hitler explained that Nazism would have to be just as intolerant to supplant Christianity:

A philosophy filled with infernal intolerance will only be broken by a new idea, driven forward by the same spirit, championed by the same mighty will, and at the same time pure and absolutely genuine in itself. The individual may establish with pain today that with the appearance of Christianity the first spiritual terror entered in to the far freer ancient world, but he will not be able to contest the fact that since then the world has been afflicted and dominated by this coercion, and that coercion is broken only by coercion, and terror only by terror. Only then can a new state of affairs be constructively created.

Hitler’s anti-Christian sentiment shines through clearly here, as he called Christianity a “spiritual terror” that has “afflicted” the world. Earlier in the passage, he also argued Christian intolerance was a manifestation of a Jewish mentality, once again connecting Christianity with the people he most hated. Even more ominously, he called his fellow Nazis to embrace an intolerant worldview so they could throw off the shackles of Christianity. He literally promised to visit terror on Christianity. Even though several times later in life, especially before 1934, Hitler would try to portray himself as a pious Christian, he had already blown his cover.

Hitler’s tirade against Christianity in Mein Kampf, including the threat to demolish it, diverged remarkably from his normal public persona… In January 1937, Goebbels was with Hitler during an internecine debate on religion and reported, “The Führer thinks Christianity is ripe for destruction. That may still take a long time, but it is coming.”

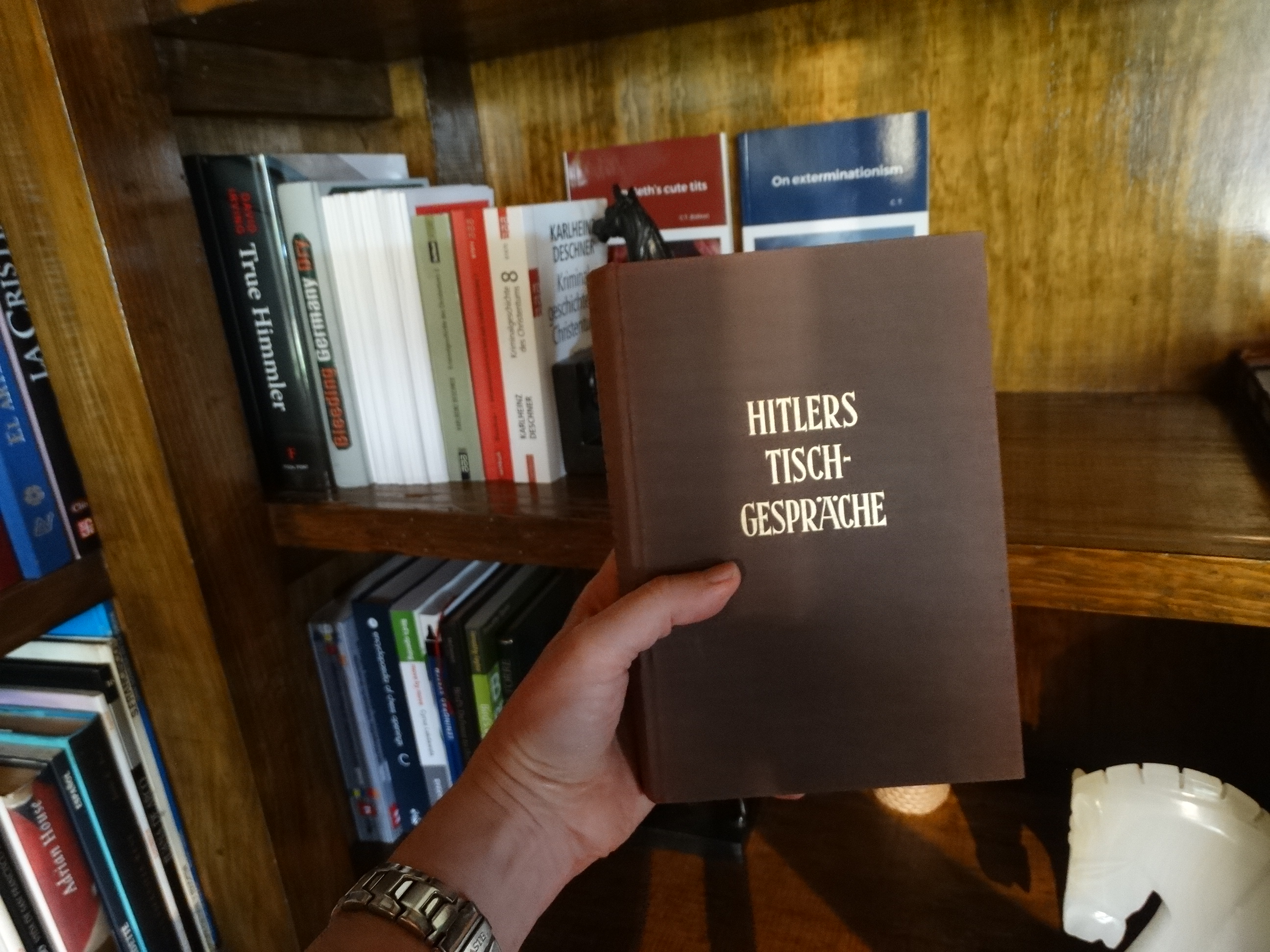

In reading through Goebbels’ Diaries, Hitler’s monologues, and Rosenberg’s Diaries, it is rather amazing how often Hitler discussed religion with his entourage, especially during World War II. He was clearly obsessed with the topic. On December 13, 1941, for example, just two days after declaring war on the United States, he told his Gauleiter (district leaders) that he was going to annihilate the Jews, but he was postponing his campaign against the church until after the war, when he would deal with them. According to Rosenberg, both on that day and the following, Hitler’s monologues were primarily about the “problem of Christianity.” In a letter to a friend in July 1941, Hitler’s secretary Christa Schroeder claimed that in Hitler’s evening discussions at the headquarters, “the church plays a large role.” She added that she found Hitler’s religious comments very illuminating, as he exposed the deception and hypocrisy of Christianity. Hitler’s own monologues confirm Schroeder’s impression…

When Hitler told his Gauleiter in December 1941 that the regime would wait until after the war to solve the church problem, he was probably trying to restrain some of the hotheads in his party. But he also promised the day of reckoning would eventually come. He told them, “There is an insoluble contradiction between the Christian and a Germanic-heroic worldview. However, this contradiction cannot be resolved during the war, but after the war we must step up to solve this contradiction. I see a possible solution only in the further consolidation of the National Socialist worldview”…

At a cabinet meeting in 1937, Hitler commented, “I know that my un-Christian Germanic SS units with their general non-denominational belief in God can grasp their duty for their people (Volk) more clearly than those other soldiers who have been made stupid through the catechism.” Hitler’s contempt for Christianity could hardly have been more palpable.

Hitler’s press chief, Otto Dietrich, confirmed Frank’s impression. In private, according to Dietrich, Hitler was uniformly antagonistic to Christianity. Dietrich wrote in his memoirs:

…Primitive Christianity, he declared, was the “first Jewish-Communistic cell”…

Dietrich stated, “Hitler was convinced that Christianity was outmoded and dying. He thought he could speed its death by systematic education of German youth. Christianity would be replaced, he thought, by a new heroic, racial ideal of God.” This confirms the point Goebbels made in his diary—that Hitler hoped ultimately to replace Christianity with a Germanic worldview through indoctrination of children…

[Albert] Speer recalled a conversation in which Hitler was told that if Muslims had won the Battle of Tours, Germans would be Muslim. Hitler responded by lamenting Germany’s fate to have become Christian: “You see, it’s been our misfortune to have the wrong religion. Why didn’t we have the religion of the Japanese, who regard sacrifice for the Fatherland as the highest good? The Mohammedan religion too would have been much more compatible to us than Christianity. Why did it have to be Christianity with its meekness and flabbiness?” As this conversation reveals, Hitler saw religion not as an expression of truth, but rather as a means or tool to achieve other ends—namely, the preservation and advancement of the German people or Nordic race. In April 1942, Hitler again compared Christianity unfavorably with Islam and Japanese religion. In the case of Japan, their religion had protected them from the “poison of Christianity,” he opined…

In fact, Hitler contemptuously called Christianity a poison and a bacillus and openly mocked its teachings… After scoffing at doctrines such as the Fall, the Virgin Birth, and redemption through the death of Jesus, Hitler stated, “Christianity is the most insane thing that a human brain in its delusion has ever brought forth, a mockery of everything divine.” He followed this up with a hard right jab to any believing Catholic, claiming that a “Negro with his fetish” is far superior to someone who believes in transubstantiation. Hitler… believed black Africans were subhumans intellectually closer to apes than to Europeans, so to him, this was a spectacular insult to Catholics… Then, according to Hitler, when others did not accept these strange teachings, the church tortured them into submission…

Another theme that surfaced frequently in Hitler’s monologues of 1941-42 was that the sneaky first-century rabbi Paul was responsible for repackaging the Jewish worldview in the guise of Christianity, thereby causing the downfall of the Roman Empire. In December 1941, Hitler stated that although Christ was an Aryan, “Paul used his teachings to mobilize the underworld and organize a proto-Bolshevism. With its emergence the beautiful clarity of the ancient world was lost.” In fact, since Christianity was tainted from the very start, Hitler sometimes referred to it as “Jew-Christianity”… He denigrated the “Jew-Christians” of the fourth century for destroying Roman temples and even called the destruction of the Alexandrian library a “Jewish-Christian deed.” Hitler thus construed the contest between Christianity and the ancient pagan world as part of the racial struggle between Jews and Aryans.

In November 1944, Hitler described in greater detail how Paul had corrupted the teachings of Jesus…

Hitler’s preference for the allegedly Aryan Greco-Roman world over the Christian epoch shines through clearly in Goebbels’s diary entry for April 8, 1941… “The Führer is a person entirely oriented toward antiquity. He hates Christianity, because it has deformed all noble humanity.” Goebbels even noted that Hitler preferred the “wise smiling Zeus to a pain-contorted crucified Christ,” and believed “the ancient people’s view of God is more noble and humane than the Christian view.” Rosenberg recorded the same conversation, adding that Hitler considered classical antiquity more free and cheerful than Christianity with its Inquisition and burning of witches and heretics. He loved the monumental architecture of the Romans, but hated Gothic architecture. The Age of Augustus was, for Hitler, “the highpoint of history.”

From Hitler’s perspective, Christianity had ruined a good thing. In July 1941 he stated, “The greatest blow to strike humanity is Christianity,” which is “a monstrosity of the Jews. Through Christianity the conscious lie has come into the world in questions of religion.” Six months later, he blamed Christianity for bringing about the collapse of Rome. He then contrasted two fourth-century Roman emperors: Constantine, also known as Constantine the Great, and Julian, nicknamed Julian the Apostate by subsequent Christian writers because he fought against Christianity and tried to return Rome to its pre-Christian pagan worship. Hitler thought the monikers should be reversed, since in his view Constantine was a traitor and Julian’s writings were “pure wisdom.” Hitler also expressed his appreciation for Julian the Apostate in October 1941 after reading Der Scheiterhaufen: Worte grosser Ketzer (Burned at the Stake: Words of Great Heretics) by SS officer Kurt Egger. This book contained anti-Christian sayings by prominent anticlerical writers, including Julian, Frederick the Great, Nietzsche, Schopenhauer, Goethe, Lagarde, and others. It was a shame, Hitler said, that after so many clear-sighted “heretics,” Germany was not further along in its religious development… A few days later, Hitler recommended that Eggers’s book should be distributed to millions because it showed the good judgment that the ancient world (meaning Julian) and the eighteenth century (i.e., Enlightenment thinkers) had about the church.

This notion that Christianity was a Jewish plot to destroy the Roman world was a theme Hitler touched on throughout his career, from his 1920 speech “Why Are We Anti-Semites?” to the end of his life. It made a brief appearance in his major speech to the Nuremberg Party Rally in 1929, and reappeared in a February 1933 speech to military leaders. In a small private meeting with his highest military leaders and his Foreign Minister in November 1937, Hitler told them that Rome fell because of “the disintegrating effect of Christianity.” From the way that Hitler bashed a generic “Christianity” as a Jewish-Bolshevik scheme, it seems clear that he was targeting all existing forms of Christianity…

During a monologue on December 14, 1941, Hitler divulged a decisive distaste for Protestantism. That day, Hitler learned Hanns Kerrl, a Protestant who was his minister for church affairs, had passed away. Hitler remarked, “With the best intentions Minister Kerrl wanted to produce a synthesis of National Socialism and Christianity. I do not believe that is possible.” Hitler explained that the form of Christianity with which he most sympathized was that which prevailed during the times of papal decay. Regardless of whether the pope was a criminal, if he produced beauty, he is “more sympathetic to me than a Protestant pastor, who returns to the primitive condition of Christianity,” Hitler declared. “Pure Christianity, the so-called primitive Christianity… leads to the destruction of humanity; it is unadulterated Bolshevism in a metaphysical framework.” In other words, Hitler preferred Leo X, the great Renaissance patron of the arts who excommunicated Luther, to the Wittenberg monk who called the church back to primitive, Pauline Christianity. According to Rosenberg’s account of this same conversation, Hitler specifically mentioned the corrupt Renaissance Pope Julius II, Leo X’s predecessor, as being “less dangerous than primitive Christianity”…

(Note of the Editor: Left, The monument of Julius II, with Michelangelo’s statues of Moses, with Rachel and Leah). Many anti-Semites in early twentieth-century Germany despised the Old Testament as the product of the Jewish spirit, and Hitler was no exception. He saw the Old Testament as the antithesis of everything he stood for. In his view, it taught materialism, greed, and deception. Further, it promoted racial purity for the Jews, since it taught them to avoid mingling with other races…

Moreover, Hitler lamented that the Bible had been translated into German, because this made Jewish doctrines readily available to the German people. It would have been better, he stated, if the Bible had remained only in Latin, rather than causing mental disorders and delusions…

Many SS members followed Himmler’s example and encouragement to withdraw from the churches, and Hitler lauded them for their anti-church attitude. Hitler once advised Mussolini to try to wean the Italian people away from the Catholic Church, lest he encounter problems in the future. When Mussolini asked how to do this, Hitler turned to his military adjutant and asked him how many men in Hitler’s entourage attended church. The adjutant replied, “None”…

In the end… he [Hitler] had utter contempt for the Jesus who told His followers to love their enemies and turn the other cheek. He also did not believe that Jesus’s death had any significance other than showing the perfidy of the Jews, nor did he believe in Jesus’s resurrection.