against the Cross, 15

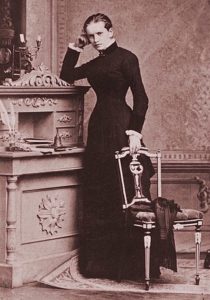

Of French origin, although German was the family language, Lou Salomé’s Huguenot ancestors arrived in St Petersburg in 1810. Her father Gustav Salomé had a successful military career and was appointed inspector of the army by Tsar Alexander II. He later married Louise Wilm, of Danish descent, nineteen years younger. The marriage produced six children: after five boys, a cute girl who was named after her mother.

Louise (later called Lou) grew up in a male environment, just the opposite of Nietzsche, who grew up in a female environment after his father’s untimely death. Lou’s birth coincided with the day of the abolition of slavery in Russia. As liberalism—what we call neo-Christianity—claims more and more equality, the abolition of slavery was the antecedent of equal rights for women: an ideal that appeared early in Lou’s life. Thus, contrary to the rules of her time, the teenager refused to receive religious confirmation.

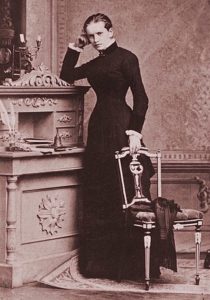

At the age of eighteen, Lou began her studies under the guidance of Pastor Hendrick Gillot, who had her study the philosophers. Thin, blonde, flirtatious and with deep blue eyes, Gillot soon fell in love with her, ready to leave his family to marry the precocious brat, but Lou rejected him outright and realised that she had to go abroad. Her mother decided to accompany her.

The first destination was Zurich, where Gottfried Kinkel, an apostle of women’s rights at universities, was teaching (the University of Zurich was the only university at the time that accepted women). Falling ill with a lung condition, Lou travelled to warmer climes in search of therapy, and with her mother came to Rome. Kinkel had recommended that they meet Malwilda von Meysenburg (Nietzsche’s very close friend), at whose house literary gatherings were held. In February 1882 Malwilda received the young Russian woman, who dressed sternly and never wore feminine ornaments. Paul Rée met her there and soon fell in love with her, but it occurred to both Rée and Malwilda to introduce Lou to Nietzsche.

He was then on one of his eternal healing journeys, always in search of a clear, cloudless sky, and had been to Messina. It is curious to note that when Nietzsche received Rée’s invitation, he replied with humour that indicated that he had overcome the depression that had led him to believe he would die at his father’s age: ‘I shall soon launch myself on the assault on her. —I need it in consideration of what I want to do for the next ten years’. He who yesterday was a candidate for death is now thinking of the great life!

When Nietzsche arrived in Rome he inquired where he could find Rée, and was told that he was visiting the Vatican. He went there to find him, who was with Lou, and asked them: ‘From which stars have we fallen to meet each other here?’ The retired professor was sixteen years older than Lou, who, at twenty-one, would soon captivate him with her feminine charms.

The ‘Trinity’, as the freethinkers Nietzsche, Rée and Lou called their alliance, had a problem: both father and son fell in love with the holy spirit, which would eventually arouse great jealousy on Nietzsche’s part, as they both made marriage proposals.

For Lou’s self-esteem—Rée bombarded her with letters—, it was in her interest to continue collecting men whose proposals she had rejected since her experience with her mentor Gillot. Thus, the following weeks and months passed with great sorrow for the lovers, who had never before faced such a woman. Nietzsche in particular, now almost in his forties, had fallen in love like an adolescent, so much so that he was now willing to go to Bayreuth if Lou would accompany him, and precisely at the premiere of Parsifal, even if it was a Christian play! Nietzsche would have given anything to travel with Lou to the premiere, and he wrote to his sister notifying her that he had regained his health, adding: ‘I no longer want to be alone and wish to learn to be a man again’. Elisabeth would meet Lou in Jena.

It is unnecessary to go into the details, but in discussing some of Nietzsche’s indecorous proposals, Elisabeth and Lou became deadly enemies—enemies, as only women can be to each other. Suffice it to say that the whole pathetic episode of Rée and Nietzsche’s falling in love, which separated the two friends, shows that this pair had no experience whatsoever with women, let alone liberated women. The philosopher who would preach that when a man goes out with a woman he should never forget the whip allowed himself to be photographed, literally, with a woman holding a whip behind him! Even in his amorous letters, the typical mistake of the inexperienced bachelor in his dealings with women is evident. Instead of being masculine, Nietzsche behaved like a supplicant bridegroom in search of the bride’s ‘yes’:

My dear Lou!

Sorry about yesterday!

A violent attack of my stupid headaches—today they have passed.

And today I see some things with new eyes.

At noon I’ll accompany Dornburg, but before that, we still have to talk for half an hour… yes?

Yes!

F.N.

It didn’t occur to the poorly pensioned man, clumsy and almost blind when he walked, that these weren’t ways of winning her over, least of all a woman of steel like Lou, brought up among Aryan men with connections in the army.

When Nietzsche would later become disappointed with Lou, he would write things like ‘frightfully repressed sensuality / delayed motherhood—due to sexual atrophy and delay’. Of course, at Schulpforta the children were never taught that male sexuality is literally a thousand per cent more intense than female sexuality, and perhaps Nietzsche believed that Lou’s sexuality wouldn’t be much different from his! Interestingly, in that list of Lou’s faults that Nietzsche noted, we read that one of them was that she was not ‘docile’.

Nietzsche had in mind not a new philosophical system but rather a new religion. And as a new religion that despised the weak and ennobled the strong, what he now needed was a new metaphysics and disciples, and in his fantasies he had designated Lou and Rée as the first. It didn’t occur to him that he was forcing things, that they both had their own goals in life. For example, the way he wanted to overcome the competition was incredibly clumsy. In Lebensrückblick (Life Review), Lou informs us that nothing had damaged her image of Nietzsche more than his attempts to demean Rée, and although the word wasn’t yet used, she blames him for lack of empathy: not realising that such a crude tactic was immediately detected as such.

Lou didn’t need Nietzsche. Nietzsche, the eternal bachelor whom Wagner had psychoanalysed well—to appease Eros the professor badly needed to get married!—did need Lou. Or rather, he didn’t need this liberated woman but one of the many ‘docile’ old-fashioned educated little women who at that time it wasn’t so difficult to ask for their hands. But the way Nietzsche wanted to pull her into his gravitational field was simply to imagine her as an apostle for his budding religion. In a letter to Overbeck, Nietzsche confessed: ‘At the moment—I don’t yet have a single disciple’. And in a missive to Malwilda, he clarifies: ‘By “disciple” I would understand a person who would swear an oath of unconditional fidelity to me—and for that, he would have to undergo a long period of trial and overcome difficult undertakings’.

The most sophisticated readers of Nietzsche’s work are unaware of his biography! It is very clear, from his own words, that he wanted to form a new cult. From this point of view the two scholarly, heavy treatises that Heidegger wrote about his favourite philosopher which begin with the lapidary sentence ‘Nietzsche, the name of the thinker attests to the content of his thought’ are rubbish! In the hundreds of pages that follow, Nietzsche the man is altogether missing, only his philosophical ‘insights’ are present!

Let’s not forget that Heidegger acknowledged to have read Luther. Much of the mission of the priest of holy words is to shake off the metaphysical cobwebs of the neo-theologians and to philosophise from the real world: the real biography of an Aryan man, the protection of his race and the analysis of his enemies.

It is more than significant that, before his death, the neo-theologian Heidegger claimed that philosophy had come to an end and that now ‘Only a God can save us’. He also claimed that for only a few months he had believed in National Socialism, and that during his ten months as rector of the University of Freiburg he refused NS orders to put up an anti-Jewry poster; to remove works by Jewish authors from the library, and to allow the burning of books at the university. But on one thing I agree with Heidegger: academic philosophy (i.e., neo-theology) is dead. The religion of sacred words must emerge, stripped now from all Christian vestiges, and not in the form of ontologies written in corrupted German.

Nietzsche wanted to create a religion very different from ours (the 14 and 4 words). In her Friedrich Nietzsche in seinen Werken, published when the philosopher was already mad, Lou would reveal juicy anecdotes that open a window into his mind. In their conversations, Nietzsche revealed to Lou that he wanted to spend a decade of his life studying the natural sciences in order to obtain a scientific basis for his theory of the eternal return! Lou adds: ‘Only after whole years of absolute silence did he intend… to appear among men as the master of the eternal return’. The following passage is key to understanding how Nietzsche wanted to drag Lou toward the dark side of the force so to speak, as if this woman was to become a sort of Sith apprentice in the wake of the philosopher’s terrible revelation:

Then he rose to take his leave, and as we stood on the threshold his features suddenly transformed. With a fixed expression on his face, casting fearful glances around him, as if a terrible danger threatened us should any curious person eavesdrop on his words, muffling the sound of his voice with a hand to his mouth, he announced to me in a whisper the ‘secret’ that Zarathustra had whispered into the ear of Life, to which Life would have replied: ‘Do you know, Zarathustra? No one knows’. There was something extravagant—indeed, sinister—in the way Nietzsche communicated to me ‘the eternal return of the identical’, and the incredible transcendence of this idea.

In Freemasonry, they speak of ‘The Great Secret’ that only the highest initiates can have access to. What Lou says was the great secret of the religion that Nietzsche now wanted to inaugurate.

That the pensioned philologist wanted to make a new religion out of such an idea is noticeable in that he even wanted to erase the fact that this idea was traceable to his readings of Heraclitus. Instead, he wanted us to believe that Zarathustra arrived at the great secret by himself. The critic of mysticism had himself fallen into the initiatory practices of the ancient Greeks. Recall that for the Pythagoreans some mathematical findings were to be hidden from the people. Only the initiated were qualified for this knowledge, such as the existence of the dodecahedron.

But Heraclitus was not Zarathustra. Nietzsche put something of his own into this doctrine since he didn’t want it to be merely an updating of the old one.

It is not the professional philosophers, like Heidegger et al, who get to the heart of the matter but the biographers, and sometimes the translators. If any scholars had to delve into the marrow of Nietzsche’s thought, it was his translators into English and Spanish: Reginald John Hollingdale (1930-2001) and Andrés Sánchez Pascual (1936-). It was precisely because of Sánchez Pascual’s translations that I began to read Nietzsche in 1976 when I was seventeen years old; translations accompanied by countless erudite footnotes, without which it would have been impossible for me to understand the obscure passages of Nietzsche’s legacy.

Hollingdale for his part made me see that Nietzsche had mixed what he had read in Schulpforta about Heraclitus with the ruthless Lutheran pietism with which he had been brought up—programmed, rather—: a mixture of Christian beatitudes with the terror of eternal damnation.

Let us remember what we have called on this site parental introjects, and that Nietzsche came from a family of theologians in both his father’s and his mother’s line. From his childhood, he had been imprinted with the idea of infinite individual responsibility in every personal affair, which would result in either reward or punishment. From this Nietzsche derived, according to R.J. Hollingdale, the idea of his new metaphysics. The question ‘Is this how you would do it an infinite number of times?’ or the imperative ‘Let us live in such a way that we wish to live again and live like this eternally!’ surpass even the categorical imperative of the other German philosopher whose Id had also been shattered by the bogeyman of the pietistic superego: Kant.

On the eternal return of the identical Nietzsche said that ‘a doctrine of this kind is to be taught as a new religion’, Zarathustra’s gospel. But even though it was a post-theistic religion, it was still in some ways the old one. This reminds me of what someone who was in Freemasonry once told me: that to enter that cult, the candidate was required to believe in the immortality of the human soul. In other words, it doesn’t matter that 19th-century Freemasons were rabid anti-clericals: they were still slaves to parental introjects (unlike Nietzsche, they even asked the novice to believe in the existence of God).

Hollingdale hit the nail. In his introduction to his translation of the Zarathustra, he interprets Nietzsche’s Amor fati as the Lutheran acceptance of life’s events as divinely willed, and the implication is that to hate our fate is blasphemous. For if in Lutheran pietism the events of life are divinely willed, it is impiety to wish that things should have turned out differently than they did.

Thus, the Nietzschean doctrine of eternal return was strongly influenced by Christian concepts of eternal life. Same song, different tune. When Hollingdale published a biography of Nietzsche, professor Marvin Rintala responded in The Review of Politics in January 1969 with a review saying that Hollingdale had failed to understand the essence of Pietist Lutheranism: ‘The great petition of the Lord’s Prayer is for Pietists “Thy will be done”.’ In his introduction to Penguin Books’ Thus spoke Zarathustra released after the biography of Nietzsche he had published, Hollingdale was honest enough to concede that he stood corrected, and writes: ‘This is much in line with the Christian origin of the conception of Zarathustra that I ought to have guessed even if I did not know it’.

Like the Freemasons, and despite the anti-clericalism that Nietzsche shared with them, none of them was free of the malware that our parents installed in our souls. With his Zarathustra, Nietzsche himself thus became a neo-theologian, and the same could be said of the much more recent New Age, and even of secular neo-Christianities as I have so often exposed on this site. There is always a neo-theological tail that drags even the most radical racialist into the abyss, as Balrog’s whip of fire dragged Gandalf into the bowels of the earth. Our mission is to cleanse these last vestiges of Christian programming, however recondite they may be hidden in the Aryan collective unconscious: something that can be done by fulfilling the commandment of the Delphic oracle, to know thyself (which is why I have written introspective autobiography).

But let us return to our biographee. By post, Nietzsche received a refusal from Lou, who went alone to Bayreuth where she had a great time and would even meet the great Wagner himself. (These were times when Nietzsche, for his part, was to receive the printing proofs of The Gay Science.) Never was he so close to despair and suicide as in the winter that followed his farewell to Lou. Eventually, this smart woman would write the novel Im Kampf um Gott (The Struggle for God). The central character is the son of a parish priest who falls in love with a girl…

‘Poor Nietzsche’—Wagner’s expression—didn’t impregnate Lou. But nine months after his amorous disaster, and in the greatest intoxication of Dionysian inspiration he ever suffered, he gave birth to his most beloved son, Thus Spoke Zarathustra. Like Dante who never savagely possessed the body of his Beatrice he coveted so much—which is what he really needed instead of terrorising the Aryan man with hellish nonsense—, Nietzsche thus transformed his tragicomic private life into the high flights of lyricism, pushing the expressive power of the German language to its limits like no other poet.