Rupture: How Christ hijacked

the moral compass of the West

The English word “virtue” is derived from the Roman word virtus, meaning manliness or strength. Virtus derived from vir, meaning “man”. Virilis, an ancestor of the English word “virile”, is also derived from the Roman word for man.

From this Roman conception of virtue, was Jesus less than a man or more than a man? Did the spectacle of Jesus dying on a Roman cross exemplify virtus; manliness; strength; masterliness; forcefulness? Consistent with his valuation of turning the cheek, it would seem that Jesus exemplified utterly shamelessness and a total lack of the manly honor of the Romans.

Yet the fame of his humiliation on the cross did, in a sense, exemplify a perverse variety of virtus, for Jesus’s feminine, compassionate ethics have mastered and conquered the old pagan virtues of the gentiles. Jesus’s spiritual penis has penetrated, disseminated, and impregnated the West with his “virtuous” seed. And it is from that seed that “modernity” has sprouted.

Jesus combined the highest Roman virtue of dying honorably in battle with highest Jewish virtue of martyrdom and strength in persecution. This combination formed a psychic bridge between pagan and Jew, i.e. between ideal cruelty in war and ideal compassion in peace. This is one way in which Christianity became the evolutionary missing link between the more masculine ethos of the ancient pagan West and the more feminine ethos of the modern West.

The original Enlightenment notion of revolution reflects a quasi-creationist view of change that makes the sudden rupture between the moral assumptions of the ancient and modern world almost inexplicable. However, if we take a more gradualistic view of social change wherein modern egalitarianism evolved from what preceded it, then the origins of modern political assumptions become more explicable. The final moral-political rupture from the ancients became possible, in part, because Christianity acted as an incubator of modern values.

Christian notions of “virtue” were not an outright challenge to pagan Roman virtue by accident; these values were incompatible by design. To even use the Roman term “virtue” to describe Christian morality is an assertion of its victory over Rome. The success of the Christian perversion of the manliness of Roman “virtue” is exemplified by its redefinition as the chastity of a woman.

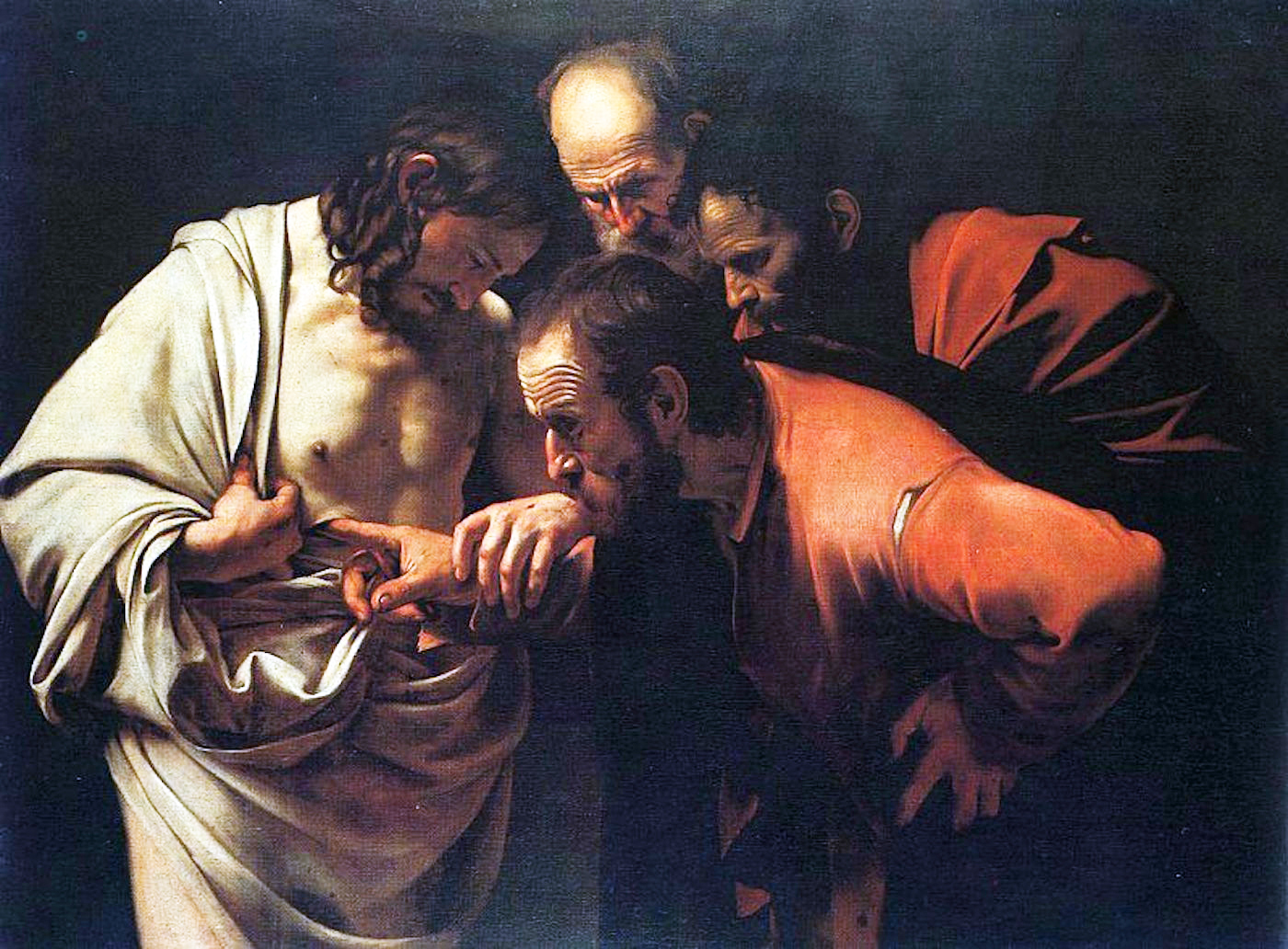

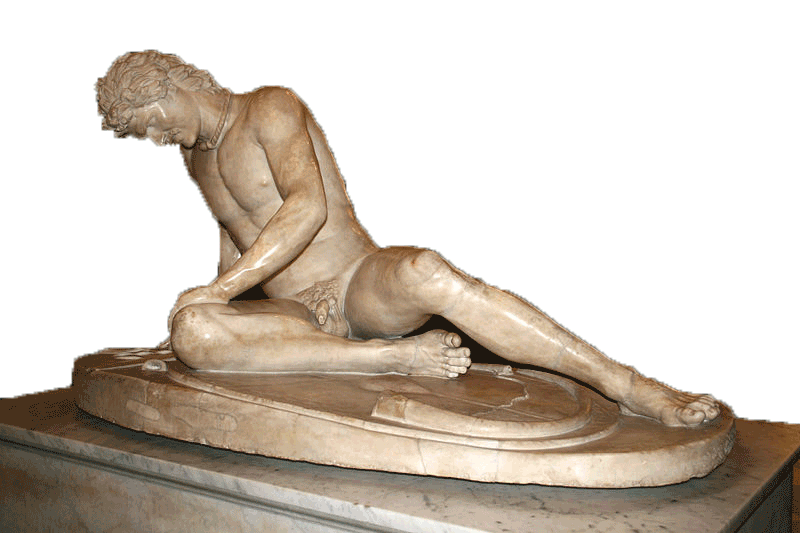

A general difference between ancient Greco-Roman virtue and modern virtue can be glimpsed through the ancient sculpture, the Dying Gaul. The sculpture portrays a wounded “barbarian”. Whereas moderns would tend to imitate Christ in feeling compassion for the defeated man, its original pagan cultural context suggests a different interpretation: the cruel defeat and conquest of the barbarian as the true, the good, and the beautiful.

The circumstances of the sculpture’s origins confirm the correctness of this interpretation. The Dying Gaul was commissioned by Attalus I of Pergamon in the third century AD to celebrate his triumph over the Celtic Galatians of Anatolia. Attalus was a Greek ally of Rome and the sculpture was only one part of a triumphal monument built at Pergamon. These aristocratic trophies were a glorification of the famous Greco-Roman ability to make their enemies die on the battlefield.

A Christian is supposed to view Christ on the cross as an individual being, rather than as a powerless peasant of the despised Jewish people. If one has faith in Jesus, then one “knows” that to interpret Jesus as the member of a racial-religious group is wrong and we “know” that this interpretation is wrong. How do we “know” this? Because we have inherited the Christianity victory over Rome in that ancient war for interpretation.

Liberalism continues the Christian paradigm by interpreting Homo sapiens as individuals, rather than members of groups such as racial groups. If it is wrong to assume Jesus can be understood on the basis of group membership, then the evolutionary connection between Christianity and modern liberalism becomes clearer. Jesus was a paradigmatic individual exception to group rules, and his example, universalized, profoundly influenced modern liberal emphasis on individual worth in contradistinction to assumptions of group membership.

Love killed honor. The values of honor and shame are appropriate for group moralities where the group is valued over “the individual”. Crucially, such a morality is inconceivable without a sense of group identity. Jesus’s morality became liberated from a specifically Jewish group identity. Once it dominated gentile morality, it also eroded kin and ethnic identity. The Christian war against honor moralities became so successful and traditional [that] its premodern origins were nearly forgotten along with the native pagan moralities it conquered.

Jesus’s values implicated the end of the hereditary world by living the logical consequences of denying the importance of his hereditary origins. This is a central premise underlying the entire modern rupture with the ancient world: breaking the import of hereditary origins in favor of individual valuations of humans. In escaping the consequences of a birth that, in his world, was the most ignoble possible, Jesus initiated the gentile West’s rupture with the ancient world.

The rupture between the ancient and the modern is the rupture between the rule of genes and the rule of memes. The difference between ancient and modern is the difference between the moral worlds of Homer and the Bible. It is the difference between Ulysses and Leopold Bloom.

On Nero’s persecution of the Christians, Tacitus wrote, “even for criminals who deserved extreme and exemplary punishment, there arose a feeling of compassion; for it was not, as it seemed, for the public good, but to glut one man’s cruelty, that they were being destroyed.” The modern morality of compassion begins with Christianity’s moral attack on the unholy Roman Empire. Christianity demoralized the pagan virtues that upheld crucifixion as a reasonable policy for upholding the public good.

If, as Carl Schmitt concluded, the political can be defined with the distinction between friend and enemy, then Jesus’s innovation was to define the political as enemy by loving the enemy, and thus destroying the basis of the distinctly political. The anarchy of love that Christianity spread was designed to make the Roman Empire impossible. The empire of love that Paul spread was subversive by design. It was as subversive as preaching hatred of the patriarchal family that was a miniature model for worldly empire.

Crossan and Reed found that those letters of Paul that are judged historically inauthentic are also the ones that carry the most inegalitarian message. It appears that their purpose was to “insist that Christian families were not at all socially subversive.” These texts “represent a first step in collating Christian and Roman household ethics.” For these historians the issue is “whether that pseudo-Pauline history and theology is in valid continuity with Paul himself or is, as we will argue, an attempt to sanitize a social subversive, to domesticate a dissident apostle, and to make Christianity and Rome safe for one another.”

What could be more ridiculous that the idea that Jesus’s attack on Roman values would not need some “modification” before making themselves at home in Rome? Jesus and Paul were heretics of mainstream or Pharisaic Judaism and rebels against Rome. Since the purity and integrity of the internal logic of Christianity is hostile to purely kin selective values, there is no way whatsoever that Christianity could survive as a mass religion without corrupting Jesus’s pure attitude towards the family. Jesus’s values subvert the kin selective basis of family values.

That subversion was part of the mechanism that swept Christianity into power over the old paganism, but it was impossible that Christianity maintain its hold without a thorough corruption of Jesus’s scandalous attacks on the family. If not this way, then another, but the long-term practical survival of Christianity required some serious spin doctoring against the notion that Jesus’s teachings are a menace to society.

These, then, are the two options: the pure ethics of Jesus must be perverted or obscured as models for the majority of people or Christianity will be considered a menace to society. The very fact that Christianity did succeed in achieving official “legitimacy” means its original subversive message was necessarily subverted. State-sanctioned Christianity is really a joke played upon on a dead man who never resurrected to speak on his own behalf.

Official Christianity was making Jesus safe for aristocracy; falsifying Jesus; subverting Jesus. Rome subverted his subversion. Jesus attempted to subvert them—and they subverted him. (Bastards!) Yet without this partial subversion of subversion, Christianity would never have taken the deep, mass hold that is its foundational strength.

This insight, that pure Christianity must be perverted in all societies that wish to preserve their kin selective family values, is a key to understanding the process of secularization. Secularization is, in part, the unsubverting of the evidence for Jesus’s original social program from its compromised reconciliation with Rome. The first truly major step towards unsubverting Rome’s subversion of Jesus’s message was the Protestant Reformation.

The Roman Catholic hierarchy contains elements of a last stand of the old Roman pagan virtue, a reminder that it had and has not been subdued completely. The Reformation begun by Martin Luther was directed, in part, against this last stand. While Luther partially continued the containment of Jesus by checking the advance of the idea that heaven should be sought on earth, this German also continued the work of the Jewish radical he worshiped in attacking the hierarchy of Rome.

Secularization is the unsubverting of Jesus’s message subverted by Christian practice. Modern liberal moral superiority over actual Christians is produced by unsubverting the subversion of Jesus’s message subverted by institutional Christianity. There is an interior logic to Jesus’s vision based on consistency or lack of hypocrisy. Liberal arguments only draw this out from its compromises with the actual social world. In this role, Protestantism was especially influential in emphasizing individual conscience over kinship-biological imperatives based on the model of the family.

The average secular liberal rejects Biblical stories as mythology without rejecting the compassion-oriented moral inheritance of the Bible as mythology. That people, still, after Nietzsche, tout these old, juvenile enlightenment critiques of Christianity would seem to be another refutation of the belief that a free and liberal society will inevitably lead to a progress in knowledge. The primitive enlightenment critique of Christianity as a superstition used as a form of social control usually fails to account that its “social control” originated as a weapon that helped to bring down the Goliath of Rome.

Still, at the beginning of the twenty-first century, this old enlightenment era castigation of Christianity for not being Christian endures without realization that this is actually the main technical mechanism of the secularization of Christian values. When one asks, what is secularization?, the attempt to criticize Christianity for its role in “oppression”, war, or other “immoral” behaviors stands at the forefront. Liberal moral superiority over actual Christians commonly stems from contrasting Christian ideals and Christian practice. This is what gives leftism in general and liberalism in particular its moral outrage.

Secularization arises as people make sense of Christian ideals in the face of its practice and even speculate as to how it might work in the real world. Enlightenment arguments for the rationalization of ethics occurred in the context of a Christian society in which the dormant premises of the Christian creed were subjected to rational scrutiny. To secularize Christianity is to follow Jesus in accusing God’s faithful believers of a nasty hypocrisy:

Woe to you, teachers of the law and Pharisees, you hypocrites! You are like whitewashed tombs, which look beautiful on the outside but on the inside are full of dead men’s bones and everything unclean. In the same way, on the outside you appear to people as righteous but on the inside you are full of hypocrisy and wickedness. (Matt. 23:27-28)

To charge Christians with hypocrisy is to relish in the irony of Jesus’s biting charges of hypocrisy against the Pharisees. Jesus’s attempt to transcend the hypocrisies inherent in Mosaic law’s emphasis on outer behavior was one germinating mechanism that produced Christianity out of Judaism. The same general pattern generated modern liberalism out of Christianity. Just as Jesus criticized the Pharisees for worshipping the formal law rather than the spirit of the law, modern liberals criticize Christians for following religious formalities rather than the spirit of compassionate, liberal egalitarianism. It was precisely Christianity’s emphasis on the spirit that helps explain how the spirit of liberal compassion evolved out of the spirit of Christianity even if the letters of the laws are different.

To recognize hypocrisy is to recognize a contradiction between theory and action. The modern ideology of rights evolved, in part, through a critique of the contradictions of Christian theology and political action. Modern ideology evolved from Christian theology. Christian faith invented Christian hypocrites, and modern political secularism seized upon these contradictions that the Christian hypocrisy industry created. Resolving these moral contradictions through argument with Christians and political authorities is what led to the idea of a single, consistent standard for all human beings: political equality. The rational basis of the secularization process is this movement towards consistency of principle against self-contradiction (hypocrisy).

Modern ideas of political rights emerged out of a dialogue; a discourse; a dialectic in which Christianity framed the arguments of secularists, defining the domain upon which one could claim the moral high ground. The “arguments” of Christian theology circumscribed the moral parameters of acceptable public discourse, and hence, the nature of the counterarguments of “secular” ideology. Secular morality evolved by arguing rationally against the frame of reference provided by the old Christian Trojan Horse and this inevitably shaped the nature of the counter-arguments that followed. Christianity helped define the basic issues of secular humanism by accepting a belief in the moral worth of the meek of the world.

The Roman who conquered Jesus’s Jewish homeland could feel, in perfect conscience, that their conquest should confirm their greatness, not their guilt. Roman religion itself glorified Mars, the god of war. Pagan Roman religion did not automatically contradict the martial spirit—it helped confirm the martial spirit.

Chivalry, the code of honor that tempered and softened the warrior ethos of Christian Europe, is the evolutionary link between pagan virtue and modern virtue. Yet the imperial vigor of the Christian West was made, not by Christian religiosity, but by Christian hypocrisy. Christianity planted in its carriers a pregnant contradiction between Christian slave morality and Christian reality that was just waiting for the exposé of the “age of reason”. Christianity made the old European aristocracies “unjust” by dissolving the prehistoric and pagan assumptions of its existence.

Jesus himself contrasted his teachings with the ways of pagans:

You know that the rulers of the Gentiles lord it over them, and their great ones are tyrants over them. It will not be so among you; but whoever wishes to be great among you must be your servant, and whoever wishes to be first among you must be your slave; just as the Son of Man came not to be served but to serve, and to give his life a ransom for many. (Matt 24:25-28)

To reverse the high political development of kin selection represented by Rome leads towards sociobiological primitivity; to an immature stage where human ontology is closest to a more primitive phylogeny; when humans are closest to our common evolutionary ancestors; when humans are biologically most equal to one another since genes and environment have not yet exacerbated differences.

Christianity reached a state of fruition called “modernity” when a kind of justice was reaped for the ancestral betrayal of a Christian’s pagan forefathers. The pagan values that genuinely supported an ancestral chain of sacrifice for their kin kind and the patriarchal kingdoms of this world were betrayed.

A war of generations broke Christianity from Judaism, and left wing humanism from Christianity. These are only peak points that matured from the gradual kneading of cultural dough; from change guided by visions of the moral high grounds in heaven or on earth. Out of a conflict between generations that Christianity helped leaven, the modern social idea of progress rose.