Editor’s note: With the subtitle of ‘Yahweh’s Trojan Horse into the Gentile City’, this essay by Laurent Guyénot was published, complete, on May 8, 2019, in The Unz Review.

Is the Church the whore of Yahweh?

I concluded an earlier article [‘Zionism, Crypto-Judaism, and the Biblical Hoax’ —Ed.] by what I regard as the most important ‘revelation’ of modern biblical scholarship, one that has the potential to free the Western world from a two-thousand-year-old psychopathic bond: the jealous Yahweh was originally just the national god of Israel, repackaged into ‘the God of Heaven and Earth’ during the Babylonian Exile, as part of a public relations campaign aimed at Persians, then Greeks and ultimately Romans. The resulting biblical notion that the universal Creator became Israel’s national god at the time of Moses, is thus exposed as a fictitious inversion of the historical process: in reality, it is the national god of Israel who, so to speak, impersonated the universal Creator at the time of Ezra—while remaining intensely ethnocentric.

The Book of Joshua is a good eye-opener to the biblical hoax, because its pre-exilic author never refers to Yahweh simply as ‘God,’ and never implies that he is anything but ‘the god of Israel,’ that is, ‘our god’ for the Israelites, and ‘your god’ for their enemies (25 times). Yahweh shows no interest in converting Canaanite peoples, whom he regards as worthless than their livestock. He doesn’t instruct Joshua to even try to convert them, but simply to exterminate them, in keeping with the war code he gave Moses in Deuteronomy 20.

However, we find in the Book of Joshua one isolated statement by a Canaanite woman that ‘Yahweh your god is God both in Heaven above and on Earth beneath’ (2:11). Rahab, a prostitute in Jericho, makes that statement to two Israeli spies who spend the night with her, and whom she hides in exchange for being spared, together with her family, when the Israelites will take over the city and slaughter everyone, ‘men and women, young and old’ (6:21). Rahab’s ‘profession of faith’ is probably a post-exilic insertion, because it doesn’t fit well with her other claim that she is motivated by fear, not by faith: ‘we are afraid of you and everyone living in this country has been seized with terror at your approach’ (2:9). Nevertheless, the combination of fear and faith is consistent with Yahweh’s ways.

The French Catholic Bible de Jérusalem—a scholarly translation by the Dominicans of the École Biblique, which served as guideline for the English Jerusalem Bible—adds a following footnote to Rahab’s ‘profession of faith to the God of Israel’, saying it ‘made Rahab, in the eyes of more than one Church Father, a figure of the Gentile Church, saved by her faith.’

I find this footnote emblematic of the role of Christianity in propagating among Gentiles the Israelites’ outrageous metaphysical claim, that great deception that has remained, to this day, a source of tremendous symbolic power. By recognizing her own image in the prostitute of Jericho, the Church claims for herself the role that is exactly hers in history, while radically misleading Christians about the historical significance of that role. It is indeed the Church who, having acknowledged the god of Israel as the universal God, introduced the Jews into the heart of the Gentile city and, over the centuries, allowed them to seize power over Christendom. [Red emphasis by Ed.]

This thesis, which I am going to develop here, may seem fanciful, because we have been taught that Christianity was strongly Judeophobic from the start. And that’s true. For example, John Chrysostom, perhaps the most influential Greek theologian of the crucial 4th century, wrote several homilies ‘Against the Jews’. But what he is concerned about, precisely, is the nefarious influence of the Jews over Christians. Many Christians, he complains, ‘join the Jews in keeping their feasts and observing their fasts’ and even believe that ‘they think as we do’ (First homily, I,5).

‘Is it not strange that those who worship the Crucified keep common festival with those who crucified him? Is it not a sign of folly and the worst madness?… For when they see that you, who worship the Christ whom they crucified, are reverently following their rituals, how can they fail to think that the rites they have performed are the best and that our ceremonies are worthless?’ (First Homily, V,1-7).

To John’s horror, some Christians even get circumcised. ‘Do not tell me,’ he warns them, ‘that circumcision is just a single command; it is that very command which imposes on you the entire yoke of the Law’ (Second Homily, II,4). And so, with all its Judeophobia (anachronistically renamed ‘anti-Semitism’ today), John Chrysostom’s homilies are a testimony to the strong influence that Jews have exerted on Gentile Christians in the early days of the triumphant, imperial Church. And no matter how much the Greek and Latin Fathers have tried to protect their flock from the influence of Jews, it has persisted as the Church expanded. It can even be argued that the history of Christianity is the history of its Judaization, from Constantinople to Rome, then from Rome to Amsterdam and to the New World.

______ 卐 ______

Note of the Editor: This is exactly what apologists of Christianity, like the secular Kevin MacDonald, fail to understand (see e.g., how he misunderstands John Chrysostom in his preface to Giles Corey’s The Sword of Christ).

______ 卐 ______

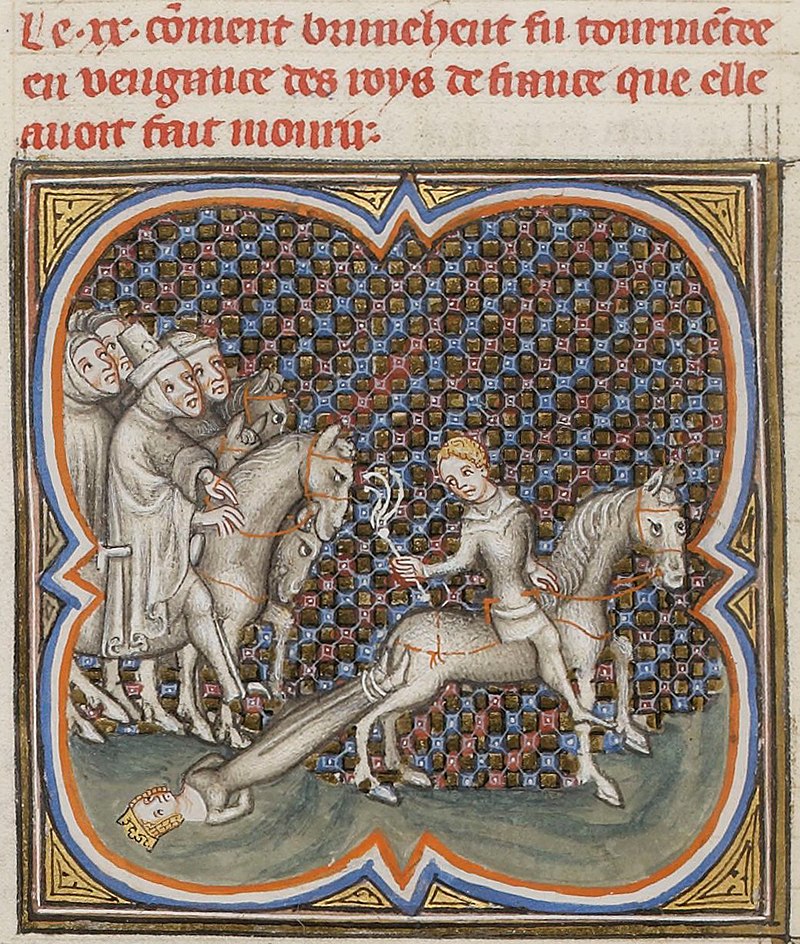

We commonly admit that the Church has always oppressed the Jews and prevented their integration unless they convert. Were they not expelled from one Christian kingdom after another in the Middle Ages? Again, this is true, but we must distinguish between the cause and the effect. Each of these expulsions has been a reaction to a situation unknown in pre-Christian Antiquity: Jewish communities gaining inordinate economic power, under the protection of a royal administration (Jews served as the kings’ tax collectors and moneylenders, and were particularly indispensable in times of war), until this economic power, yielding political power, reaches a point of saturation, causes pogroms and forces the king into taking measures.

Let us consider for example the influence of the Jews in Western Europe under the Carolingians. It reaches a climax under Charlemagne’s son, Louis the Pious. The bishop of Lyon Agobard (c. 769-840) left us five letters or treatises written to protest against the power granted to the Jews at the detriment of Christians. In On the insolence of the Jews, addressed to Louis the Pious in 826, Agobard complains that the Jews produce ‘signed ordinances of your name with golden seals’ guaranteeing them outrageous advantages, and that the envoys of the Emperor are ‘terrible towards Christians and gentle towards Jews.’ Agobard even complains of an imperial edict imposing Sunday rather than Saturday as market day, in order to please the Jews. In another letter, he complains of an edict forbidding anyone to baptize the slaves of the Jews without the permission of their masters.[1]

Louis the Pious was said to be under the influence of his wife, Queen Judith—a name that simply means ‘Jewess’. She was so friendly to Jews that the Jewish historian Heinrich Graetz hypothesizes that she was a secret Jewess, in the manner of the biblical Esther. Graetz describes the reign of Louis and Judith (and ‘the treasurer Bernhard, the real ruler of the kingdom’ according to him) as a golden age for the Jews, and points out that in the emperor’s court, many regarded Judaism as the true religion. This is illustrated by the resounding conversion of Louis’ confessor, Bishop Bodo, who took the name of Eleazar, had himself circumcised, and married a Jewess. ‘Cultured Christians,’ writes Graetz, ‘refreshed themselves with the writings of the Jewish historian Josephus and the Jewish philosopher Philo, and read their works in preference to those of the apostles.’[2]

The Judaization of the Roman Church at this time is appropriately symbolized by the adoption of unleavened bread for communion, with no justification in the Gospel. I say ‘the Roman Church’, but perhaps it should be called the Frankish Church because, from the time of Charlemagne, it was taken over by ethnic Franks with geopolitical designs on Byzantium, as Orthodox theologian John Romanides has convincingly argued.[3]

The Old Testament was especially influential in the Frankish spheres of power. Popular piety focused on the Gospel narratives (canonical gospels, but also apocryphal ones like the immensely popular Gospel of Nicodemus), the worship of Mary, and the ubiquitous cults of the saints, but kings and popes relied on a political theology drawn from the Tanakh.

The Hebrew Bible had been a major part of Frankish propaganda from the late sixth century. Gregory of Tours’ History of the Franks, the primary—and mostly legendary—source for Merovingian history, is framed on the providential ideology of the Books of Kings: the good kings are those who support the Catholic Church, and the bad kings those who resist the growth of its power. Under Louis the Pious, the rite of anointment of the Frankish kings was designed after the model of the prophet Samuel’s anointment of King David in 1 Samuel 16.

__________

[1] Adrien Bressolles, ‘La question juive au temps de Louis le Pieux,’ in Revue d’histoire de l’Église de France, tome 28, n°113, 1942. pp. 51-64, on https://www.persee.fr

[2] Heinrich Graetz, History of the Jews, Jewish Publication Society of America, 1891 (archive.org), vol. III, ch. VI, p. 162.

[3] John Romanides, Franks, Romans, Feudalism, and Doctrine: An Interplay Between Theology and Society, Holy Cross Orthodox Press, 1981.