Excerpted from the 14th article of William Pierce’s “Who We Are: a Series of Articles on the History of the White Race”:

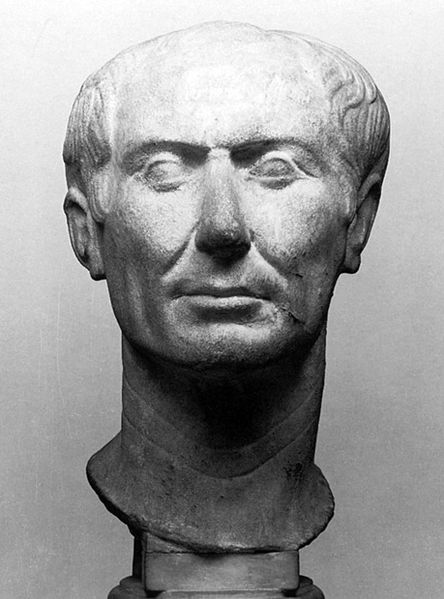

Celtic bands continued to whip Roman armies, even to the end of the second century B.C., but then Roman military organization and discipline turned the tide. The first century B.C. was a time of unmitigated disaster for the Celts. Caesar’s conquest of Gaul was savage and bloody, with whole tribes, including women and children, being slaughtered by the Romans.

By the autumn of 54 B.C, Caesar had subdued Gaul, having destroyed 800 towns and villages and killed or enslaved more than three million Celts. And behind his armies came a horde of Roman-Jewish merchants and speculators, to batten on what was left of Gallic trade, industry, and agriculture like a swarm of locusts. Hundreds of thousands of blond, blue-eyed Celtic girls were marched south in chains, to be pawed over by greasy, Semitic flesh-merchants in Rome’s slave markets before being shipped out to fill the bordellos of the Levant.

Last Effort

Then began one, last, heroic effort by the Celts of Gaul to throw off the yoke of Rome, thereby regaining their honor and their freedom, and—whether consciously or not—reestablishing the superiority of Nordic mankind over the mongrel races of the south. The ancestors of the Romans had themselves established this superiority in centuries past, but by Caesar’s time Rome had sunk irretrievably into the quagmire of miscegenation and had become the enemy of the race which founded it.

The rebellion began with an attack by Ambiorix, king of the Celtic tribe of the Eburones, on a Roman fortress on the middle Moselle. It spread rapidly throughout most of northern and central Gaul. The Celts used guerrilla tactics against the Romans, ruthlessly burning their own villages and fields to deny the enemy food and then ambushing his vulnerable supply columns.

Vercingetorix

For two bloody years the uprising went on. Caesar surpassed his former cruelty and savagery in trying to put it down. When Celtic prisoners were taken, the Romans tortured them hideously before killing them. When the rebel town of Avaricum fell to Caesar’s legions, he ordered the massacre of its 40,000 inhabitants.

Meanwhile, a new leader of the Gallic Celts had come to the fore. He was Vercingetorix, king of the Arverni, the tribe which gave its name to France’s Auvergne region. His own name meant, in the Celtic tongue, “warrior king,” and he was well named. Vercingetorix came closer than anyone else had to uniting the Celts. He was a charismatic leader, and his successes against the Romans, particularly at Gergovia, the principal town of the Arverni, roused the hopes of other Celtic peoples. Tribe after tribe joined his rebel confederation, and for a while it seemed as if Caesar might be driven from Gaul.

Tragedy of Alesia

But unity was still too new an experience for the Celts, nor could all their valor make up for their lack of the long experience of iron discipline which the Roman legionaries enjoyed. Too impetuous, too individualistic, too prone to rush headlong in pursuit of a temporary advantage instead of subjecting themselves always to the cooler-headed direction of their leaders, the Celts soon dissipated their chances of liberating Gaul.

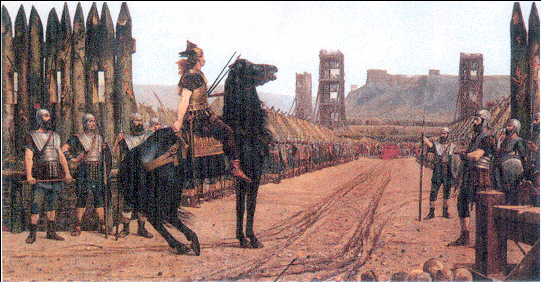

Finally, in the summer of 52 B.C., Caesar’s legions penned up Vercingetorix and 80,000 of his followers in the walled town of Alesia, on the upper Teaches of the Seine. Although an army of a quarter-million Celts, from 41 tribes, eventually came to relieve besieged Alesia, Caesar had had time to construct massive defenses for his army. While the encircled Alesians starved, the Celts outside the Roman lines wasted their strength in futile assaults on Caesar’s fortifications.

Savage End

In a valiant, self-sacrificing effort to save his people from being annihilated, Vercingetorix rode out of Alesia, on a late September day, and surrendered himself to Caesar. Caesar sent the Celtic king to Rome in chains, kept him in a dungeon for six years, and then, during the former’s triumphal procession of 46 B.C., had him publicly strangled and beheaded in the Forum, to the wild cheers of the city’s degraded, mongrel populace.

After the disaster at Alesia, the confederation Vercingetorix had put together crumbled, and Caesar had little trouble in extinguishing the last Celtic resistance in Gaul. He used his tried- and-true methods, which included chopping the hands off all the Celtic prisoners he took after one town, Uxellodunum, commanded by a loyal adjutant of Vercingetorix, surrendered to him.

Next: Germanic Expansion

Caesar did not live long enough to wreak the same havoc in Britain which he had in Gaul, but other Roman generals finished what he had started. During the first century A.D. Roman Britain was bloodily expanded to include everything in the British Isles except Caledonia (northern Scotland) and Hibernia (Ireland).

Decadent Rome did not long enjoy dominion of the Celtic lands, however, because another Indo-European people, the Germans, soon replaced the Latins as the masters of Europe.