CHAPTER 4: ONE AGAINST ALL

If the Jews are chosen by God, then everyone else is, of necessity, not chosen. If Jews are first class humans in the eyes of God, everyone else is second-class at best. And indeed, Jews do view themselves as distinct, special, and superior to others. As Exodus states, “We are distinct from all other people that are upon the face of the earth” (33:16). Similarly, the Hebrew tribe is “a people dwelling alone, and not reckoning itself among the nations” (Numbers 23:9).

Moses adds that “you shall rule over many nations” (15:6)… you shall eat the wealth of the nations” (61:5-6).

Clearly, when other people began to encounter these ideas and the attitudes that derived from them, one would expect a backlash. And there was. Hence we find a consistent thread of opinions from non-Jewish observers, for centuries, who are repelled by such arrogance…

The earliest direct references come from Aristotle’s star pupil Theophrastus. He had a concern about one of their customs: “the Syrians, of whom the Jews (Ioudaioi) constitute a part, also now sacrifice live victims… They were the first to institute sacrifices both of other living beings and of themselves”. The Greeks, he added, would have “recoiled from the entire business.” The victims—animal and human —were not eaten, but burnt as “whole offerings” to their God, and were “quickly destroyed.” The philosopher was clearly repelled by this Jewish tradition.

Egyptian high priest Manetho (ca. 250 BC) tells of a group of “lepers and other polluted persons,” 80,000 in number, who were exiled from Egypt and found residence in Judea… When in power they treated the natives “impiously and savagely,” “setting towns and villages on fire, pillaging the temples and mutilating images of the gods without restraint,” and roasting the animals held sacred by the locals. This is a very different version than we read in the Jewish Bible…

The decline of the Seleucids coincided with Roman ascent. Rome was still technically a republic in the second century BC, but its power and influence were rapidly growing. Jews were attracted to the seat of power, and travelled to Rome in significant numbers. As before, they grew to be hated. By 139 BC, the Roman praetor Hispalus found it necessary to expel them from the city: “The same Hispalus banished the Jews from Rome, who were attempting to hand over their own rites to the Romans, and he cast down their private alters from public places”. In even this short passage, one senses a Roman Jewry who were disproportionately prominent, obtrusive, even ‘pushy.’

Perhaps in part because of this incident, and in light of the Maccabean revolt some 30 years earlier, the Seleucid king Antiochus VII Sidetes was advised in 134 BC to exterminate the Jews… Apollonius Molon wrote the first book to explicitly confront the Hebrew tribe, Against the Jews.

The rhetoric is clearly heating up. In 63 BC, as we know, Roman general Pompey took Palestine. In the year 59 BC Cicero gave a speech, now titled Pro Flacco. The Jewish religion is “at variance with the glory of our empire, the dignity of our name, the customs of our ancestors.” That the gods stand opposed to this tribe “is shown by the fact that it has been conquered, let out for taxes, made a slave.”

Ten years later Diodorus Siculus wrote his Historical Library. Among other things, it again recounts the Exodus: “The refugees had occupied the territory round about Jerusalem, and having organized the nation of Jews had made their hatred of mankind into a tradition” (34, 1).

Here, though, it is Antiochus Epiphanes, not his successor Sidetes, that was urged “to wipe out completely the race of Jews, since they alone of all nations avoided dealings with any other people and looked upon all men as their enemies”.

The great lyric poet Horace wrote his Satires in 35 BC, exploring Epicurean philosophy and the meaning of happiness. At one point, though, he makes a passing comment on the apparently notorious proselytizing ability of the Roman Jews—in particular their tenaciousness in winning over others. Horace is in the midst of attempting to persuade the reader of his point of view: “and if you do not wish to yield, then a great band of poets will come to my aid, and, just like the Jews, we will compel you to concede to our crowd” (I.4.143). Their power must have been legendary, or he would not have made such an allusion.

The last commentator of the pre-Christian era was Lysimachus. Writing circa 20 BC, he offers another variation on the Exodus story. The exiled ones, led by Moses, were instructed to “show goodwill to no man,” to offer “the worst advice” to others, and to overthrow any temples or sanctuaries they might come upon. Arriving in Judea, “they maltreated the population, and plundered and set fire to the local temples.” They then built a town called Hierosolyma (Jerusalem), and referred to themselves as Hierosolymites.

The charge of misanthropy, or hatred of mankind, is significant and merits further discussion, especially in light of the Christian story.

Romans of the Christian Era

Emperor Tiberius expelled them in the year 19 AD. The expulsion did not succeed. Eleven years later, as we recall from chapter two, Sejanus found reason to oppose them again.

Anti-Jewish actions continued. In 49, Claudius once again had to expel them. In a fascinating line from Suetonius circa the year 120, we find mention of one ‘Chrestus’ (Latin: Chresto) as the leader of the rabble; this would be perhaps the fourth non-Jewish references to Jesus. “Since the Jews constantly made disturbances at the instigation of Chrestus, [Claudius] expelled them from Rome”. This is an important observation that, even at that late date, the Romans still identified Christianity with the Jews.

Despite all this, the beleaguered tribe still earned no sympathy. The great philosopher Seneca commented on them in his work On Superstition, circa 60. He was appalled not only by their ‘superstitious’ religious beliefs, but more pragmatically with their astonishing influence in Rome and around the known world, despite repeated pogroms and banishments. Seneca adds: “The customs of this accursed race (sceleratissima gens) have gained such influence that they are now received throughout all the world. The vanquished have given laws to their victors.”

Seneca is clearly indignant at their reach. Then came the historic Jewish revolt in Judea, during the years 66 to 70. The Romans were surely gratified; to their mind, the Jews received their just deserts.

In besieging Jerusalem, and consequently the mighty Jewish temple, Titus had the Jews trapped. There was thought of sparing the temple, but Titus opposed this option. For him, “the destruction of this temple was a prime necessity in order to wipe out more completely the religion of the Jews and the Christians.” These two religions, “although hostile to each other, nevertheless sprang from the same sources; the Christians had grown out of the Jews: if the root were destroyed, the stock would easily perish”. The passage closes by noting that 600,000 Jews were killed in the war.

The third and final Jewish uprising occurred just a few years later, in 132. The reasons for this were many, but two stand out: the construction of a Roman city on the ruins of Jerusalem, and Emperor Hadrian’s banning of circumcision: “At this time the Jews began war, because they were forbidden to practice genital mutilation (mutilare genitalia)”. Dio describes the conflict in detail. “Jews everywhere were showing signs of hostility to the Romans, partly by secret and partly overt acts”. They were able to bribe others to join in the uprising: “many outside nations, too, were joining them through eagerness for gain, and the whole earth, one might almost say, was being stirred up over the matter.” For those today who argue that Jews were perennially the cause of wars, this would provide some early evidence. Hadrian sent one of his best generals, Severus, to put down the insurgency. Through a slow war of attrition, “he was able to crush, exhaust, and exterminate them. Very few of them in fact survived.”

Finally we have Celsus, a Greek philosopher who composed a text, The True Word, sometime around 178. The piece is striking as an extended and scathing critique of the increasingly prominent Christian sect.

Conclusions

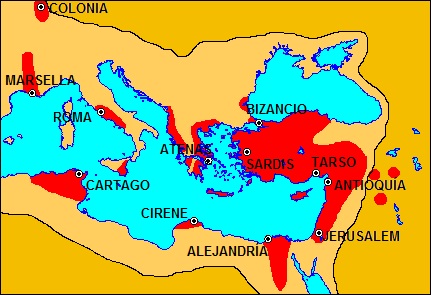

So what can we conclude from this brief overview of some 600 years of the ancient world? To say that the Jews were disliked is an understatement. The critiques come from all around the Mediterranean region, and from a wide variety of cultural perspectives. And they are uniformly negative. I note here that it’s not a case of ‘cherry-picking’ the worst comments and ignoring the good ones. The remarks are all negative; there simply are no positive opinions on the Jews or early Christians. A reasonable conclusion is that there is something about the Jewish culture that inspires disgust and hatred.

In any case, it’s clear that the Jews had few if any friends in the ancient world. Their religion instructed them to despise others (Gentiles), and others in turn despised them. But the originating source was the Jews themselves: their religion, their worldview, their values. They were willing to use and exploit non-Jews for their own ends. They were willing to kill, and to die.

This situation feeds directly into the circumstances of the Roman occupation and Paul’s reaction. The preceding analysis suggests that Paul was interested in nothing other than saving ‘Israel,’ the Jewish people. We have seen a few textual clues indicating that he was willing even to commit murder in order to further his ends. Surely he hated the Romans with a vengeance, and yet he also could see the futility of confronting them directly.