My brief optimism in those weeks did not last. Soon enough, my mood plummeted back into its soft, sad hole, and my scalpel was in my hands again. This time, I did not tell my parents. I also tried my hardest to be more careful at school, wearing a long-sleeved underlayer and bandaging my arms with elasticated crepe bandages from my mother’s medical cabinet. Though still relatively containable, the damage I was inflicting increased, as did the frequency.

In between, I drifted in moody silence, occasionally breaking into vast floods of tears, up in my bedroom, soaking my pillow, or in the downstairs’ craft room’ sat in the corner on a wooden kitchen chair, the dining room long turned over to my burgeoning library, my computer, and a table of fantasy lead figures with a painting desk to one side. Contained, or so they thought, in my historical reading habits or my miniature painting, much time was still spent by myself, my parents “giving me some space”.

However, sometimes my Dad would come in and tell me to go to bed, his tone more irritable than usual, impatient with me in conversation, and his face grim, exhausted from his gruelling work, and less inclined to talk about our usual spread of cultural interests, or indeed my feelings, curt and prescriptive, asking me simply, “have you self-harmed today?” and accepting my denial at face value, then stomping out. In the evening, murmurs came from their bedroom. Occasionally, voices were raised, and my mother would appear on the stairs in tears. […]

Here we see not only that Benjamin’s parents lacked empathy for what was happening to their son, or rather, what they had been doing to their teenage son in conjunction with the abuse at school. As if that weren’t enough the parents used psychiatry: a fraudulent profession that, without medical evidence, makes big business with Big Pharma by claiming that all mental problems are biomedical. On my Spanish-language website you can read a section in which I expose how Giuseppe Amara, the psychiatrist my mother wanted to use to break my teenage will, had a sort of unspoken slogan: “Family problems, medical solutions”.

Naturally! If someone wants to profit from the pain of others, children included, they will never, ever side with the affected party. They will always side with those who can pay for their services, no matter how surreal it may be to drug a victim of, say, school bullying instead of rescuing the child from the insulting environment. In my trilogy I call this “psychiatric revictimisation”.

In biological psychiatry the environment is never questioned. All the blame is placed on the victim: his brain or genes. That is why Benjamin’s doctor simply prescribed him SRI antidepressants without making the slightest inquiry as to whether the problem had an existential cause, as was the case.

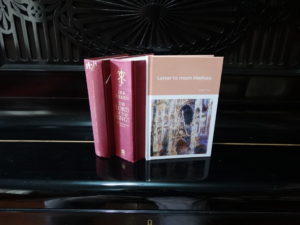

In my case, as I recount in Letter to mom Medusa, shortly after I tried to tell the psychoanalyst in his office what my parents were doing to me at home, Giuseppe Amara prescribed that they bombard my brain with the most incisive neuroleptic (even though I had no psychiatric symptoms)! Although it may seem incredible to unsuspecting readers, this is precisely how psychiatry works: the client, the father or mother, who requests his services is always right, and “he who pays the piper calls the tune” (children can never pay the so-called mental health professional).

In my case, as I recount in Letter to mom Medusa, shortly after I tried to tell the psychoanalyst in his office what my parents were doing to me at home, Giuseppe Amara prescribed that they bombard my brain with the most incisive neuroleptic (even though I had no psychiatric symptoms)! Although it may seem incredible to unsuspecting readers, this is precisely how psychiatry works: the client, the father or mother, who requests his services is always right, and “he who pays the piper calls the tune” (children can never pay the so-called mental health professional).

But Benjamin did have symptoms. I don’t want to go into the details of how he self-harmed because it is very disturbing. Anyone who wants to find out can obtain a copy of his book. I just want to reiterate what I recently said in the comments section: We explain the internal process of the self-harmer on page 40 of my book Day of Wrath, and anyone who wants to delve deeper into the subject should read the entire chapter, not just page 40. Benjamin’s story continues:

A useless, stupid form, I had no reason now to look for justifications, settled into my pattern. I was simply a sinner, a wretched waste, and each new lunge at myself, conducted with fierce, black hatred and the coldest rage, cemented my necessity to continue. After all, I was evil now, and I had disappointed my parents, let down all around me, and betrayed the words of God. And the only cure for that weakness and that criminal lack of decency was to cut it better, however long it took, to redeem myself through pain, a pain I did not, at any point, enjoy, a terrible sensation wracking my pale, sensitive skin.

I shouldn’t be allowed to escape unpunished, I thought, clear to me; it was only right. I had upset them, scared them and hurt their feelings. My poor parents. What a monster I was. My head filled with rude swear words, names for myself, “the c**t”, “the bast*rd”, “the f**king idiot”. And so the blades went in, one by one then in tandem, clasped between fingers, in wincing gasps of agony and falling skin, and the days went on. “Please”, I pleaded with myself, “mercy”. “F**k you, you pathetic bast*rd”, I answered myself silently, “you did this”, “now shut up!”

This sort of Gollum’s warfare against the healthy part of his self denotes, according to our point of view in Day of Wrath, what Colin Ross calls “the locus of control shift”: something closely related to “the problem of attachment to the perpetrator” whom we are conditioned to love as children. Benjamin then includes another disturbing paragraph about the details of his self-harm, which I will also refrain from quoting. He then writes:

“Benjamin!” my father said in snappy annoyance. “Sit down here now and stop being so antisocial.” So I sat on the black leather upholstery of the sofa for a while and tried to smile a little more, listening to my aunties tell their jokes, pretending I couldn’t feel the detestable sensation under my clothes, an ever-present sting perched there, legs together, quiet and reserved, and riddled with hundreds of sharp little scratches, my burning surface partially skinned and my clothes slightly damp, distracted and cloudy in mind, just waiting to head upstairs again. […]

Shame had become guilt, and I was fused with self-hate, my rigged moral perfectionism inverting the reality of my historical situation, inculcated from such a young age with steady doses of mental poison that I was now at a critical threshold, as if in toxic shock.

In between these bouts of auto-sadism, I was still cogent and in full cognitive clarity, my intellectual faculties otherwise unaffected, and, provided they did not persist in making inquiries or watch me like a hawk (which did not become apparent to them until much later), I found other people did not notice anything was wrong. Though the pupils had heard of my first injuries from Josh, they had no idea of the scale, and I gather most considered it an isolated incident, a ‘fad’ that I would soon grow out of.

When I returned from Ireland in the new year, binning two of my shirts before leaving, washing out the stains from my jacket lining in the sink, and packing my suitcase, I was able to blend straight back into the school environment, continuing my lessons in the commencing term, with a little SSRI tablet a day, and nothing really to add to that, to all intents and purposes getting slightly better, or so everyone thought. Much as it was well understood that “he’s got Depression”, “he did this…” and “he’s ill now”, no one, curiously, had ever paused to ask me how I felt or to inquire what actually was wrong. […]

One day, near the end of the Spring term, not long before my AS exams, I was sitting in the dorm study room with another boy named Gerald, a half- Malaysian pupil whom I had a mild friendship with […] Gerald had caught me crying also, in the dorm and various quiet parts of the school, and soon after began to distance himself again, considering me “nuts” and “a bit of a head case”, disapproving of my distress, and frustrated that I didn’t just “snap out of it”.

Psychiatry is just the tip of the iceberg. The whole problem has to do with a society that wants to know nothing about existential problems—unless they are presented in theatrical tragedies, as the Greeks did, or in modern movies where the plot can be understood even by housewives. But if someone in real life wants to communicate that she suffers from a maddening dynamics with her mother, like the self-harmer woman in the film La Pianiste, she is generally ignored not only by those close to them, but also by so-called mental health professionals.

For example, in my trilogy I recount how my mother, who really was the crazy one in the house, projected her evil onto me and sent me to various professionals over the years. None of them wanted to listen to me. But the most shocking thing is something I confess in the third volume.

Only a very traditionalist priest, whom my mother suggested I go to on the advice of Mrs Eva Grimaldi, listened to me! The reason for this wouldn’t be understood in the least unless the reader is familiar with the critical literature on all mental health professions, whether pseudo-medical like psychiatry, or mere therapy with psychoanalysts or clinical psychologists. (See, for example, Against Therapy: Emotional Tyranny and the Myth of Psychological Healing by Jeffrey Masson, with whom I exchanged a brief correspondence several years ago.)

First, marry a man who is super-affectionate with children: someone who has an extraordinary graceful charm with them and whom you can also manipulate.

First, marry a man who is super-affectionate with children: someone who has an extraordinary graceful charm with them and whom you can also manipulate.