An updated version of this entry—the featured article—has been posted here.

An updated version of this entry—the featured article—has been posted here.

Tag: Genuine spirituality

I have just modified the hatnote of the 50 films I recommended not to be bored at home when the COVID-19 epidemic started because I will no longer review those films individually.

While it is true that those films made a big impression on me as a child and young man, once I woke up to the real world, in the sense of stepping out of the System’s matrix that controls us, most of those films lost their original meaning. I prefer to continue reviewing Brendan Simms’ book about Uncle Adolf insofar as, now free from the matrix that controls the white man, I feel a moral responsibility to convey who he was under a completely different narrative from that of the ubiquitous System (a narrative that includes Simms’ POV). Nevertheless, I would like, in a single entry, to say what I think roughly about the remaining 42 films that I won’t review individually, as I did with the first eight on the list.

First of all, I have already said something about Shane, #9 on the list. (Incidentally, when the month before my dad died, I showed him the DVDs of the films we had at home to see which one my ailing father wanted to see, he chose Shane.)

About other films on my list from the 1950s, ten years ago I already said something about Ben-Hur and I don’t have much to add. The two movies that the Swede Ingmar Bergman filmed in his country the year before I was born are watchable, especially The Seventh Seal. Although Wild Strawberries is the only one, along with A.I., that made me cry, I would have to explain why I projected myself into it, and that would be getting deep into my biography, which I won’t do in this entry. (By the way, when I saw Wild Strawberries on the big screen I met, on the way out, my first cousin Octavio Augusto whom I said a few years ago he had just killed his daughter and then hanged himself.)

I already said something about Forbidden Planet in 2012 in the context of some paragraphs by the Canadian Sebastian Ronin that are worth re-reading. Of Journey to the Center of the Earth, I had already said something in 2011 (incidentally, it’s worth watching the clip of the film that I uploaded on YouTube, embedded in that post).

The other film from the 1950s, Lust for Life, I haven’t written anything about: the life of Vincent Van Gogh. Given that I have several books—huge books, by the way: those deluxe ones that seem to take up an entire table—on Vincent’s paintings, and that as a small child I tried, modestly, to copy his paintings with my watercolours, his life has a special significance.

This film was shot when the Aryans weren’t yet betraying themselves as nefariously as they do today. For those who still appreciate 19th-century Europe, it is worth seeing this novel-based interpretation of Vincent’s life. And the same can be said of Sleeping Beauty and The Time Machine: once upon a time there was an optimistic ethos about the Aryan race, with very blonde and extremely beautiful women indeed: films that one could even play to children being educated in NS.

So much for the films of the 1950s. As far as the films on my list from the 1960s are concerned, I have to say that 2001: A Space Odyssey is my favourite film, and I can conceivably write a review in the future about the film that has influenced my life the most. As for the others from that decade, I’ve already commented here and there but unlike the previous ones, I won’t link to my posts. And I can say the same about the films on my list from the seventies, except Death in Venice of which I’ll say something.

So much for the films of the 1950s. As far as the films on my list from the 1960s are concerned, I have to say that 2001: A Space Odyssey is my favourite film, and I can conceivably write a review in the future about the film that has influenced my life the most. As for the others from that decade, I’ve already commented here and there but unlike the previous ones, I won’t link to my posts. And I can say the same about the films on my list from the seventies, except Death in Venice of which I’ll say something.

As for the only film on my list from the 1980s, Fanny & Alexander, I already said what I had to say in my entry on the 50 films; and as for my recommendations of films from the 1990s, Sense and Sensibility, and Pride & Prejudice—an English TV series, although here we could also include the 2005 film—, I already said what I had to say in Daybreak (page 42) and On Beth’s Cute Tits (pages 134-135). It’s precisely in this context that Death in Venice could be understood, albeit in the sense of purely platonic admiration that is in line with what I wrote in Daybreak (pages 163-164).

As far as the films of our century from my list of 50, why A.I. caught my attention so much can be guessed from what I say in Day of Wrath (pages 32ff) in the context of the bonding or imprint we all have with our abusive parents; and about LOTR I already said something here.

If a visitor is curious about the details of how any film on my list affected me (or another film that doesn’t appear on my list, as long as I have seen it) I’m willing to answer any questions.

Solitude

Eight years ago I published an entry here under the title ‘Solitude’, in which I quoted some passages from Nietzsche’s poetic prose and then commented on them. I would like to recite some of those quotes and comment on them again, but from a more mature perspective.

Now Zarathustra looked at the people and he was amazed. Then he spoke thus: ‘Mankind is a rope fastened between animal and Overman – a rope over an abyss. What is great about human beings is that they are a bridge and not a purpose: what is lovable about human beings is that they are a crossing over and a going under’.

The lovely thing about white nationalists is that they are a crossing over and a sinking, indeed. But they don’t yet go under completely into the river so the nymph helps them finish crossing it.

‘I love the great despisers, because they are the great venerators and arrows of longing for the other shore. I love those who do not first seek behind the stars for a reason to go under and be a sacrifice, who instead sacrifice themselves for the earth, so that the earth may one day become the Overman’s. I love the one who lives in order to know, and who wants to know so that one day the Overman may live. And so he wants his sinking in his sunset’.

If anyone has read the central book of my Hojas Susurrantes, that dream I had as a child with an impressive celestial ship in the shape of a pencil and my family in the foreground in a bucolic environment, and how as a child I wanted to be in the big rocket that I saw on the horizon more than on that beautiful field day, you should know that a few years ago I transvalued my childhood values and realised that we must be faithful to the Earth since it is through self-knowledge that one can truly know the universe and become the overman.

‘I want to teach humans the meaning of their being, which is the Overman, the lightning from the dark cloud “human being”.’

Racialists are a dark cloud that could give birth to lightning bolts that would split history in twain (Savitri’s Kalki), but they still don’t give birth to them.

‘It dawned on me: I need companions, and living ones – not dead companions and corpses that I carry with me wherever I want’.

My river nymph died in 1982. Where is there someone like her on the other side of the river? It bothers me to deal only with the ghost of a person dead and cremated long ago because today’s racialists don’t dare to cross her psychological Rubicon.

‘It dawned on me: let Zarathustra speak not to the people, but instead to companions!’

I realised for a long time that going to the racial right forums to try to invite them to the other side is a fool’s errand.

‘Look at the good and the just! Whom do they hate most? The one who breaks their tablets of values, the breaker, the lawbreaker – but he is the creative one’.

They hate the hero of the Second World War, who tore up their cherished tablets of Judeo-Christian law. Once you break those tablets you realise not only that the majority of humans have no value, but that they are ranked negatively in the eyes of the overman.

‘Companions the creative one seeks and not corpses, nor herds and believers. Fellow creators the creative one seeks, who will write new values on new tablets’.

‘I do not want to even speak again with the people – for the last time have I spoken to a dead person’.

Below are some excerpts from Robert Pippin’s introduction to Nietzsche’s book.

As noted, the problem Zarathustra confronts seems to be a failure of desire; nobody wants what he is offering, and they seem to want very little other than a rather bovine version of happiness.

For example, those who belong to the racial right aren’t revolutionaries in spirit but de facto conservatives (neo-normies).

It is that sort of failure that proves particularly difficult to address, and that cannot be corrected by thinking up a ‘better argument’ against such a failure.

The events that are narrated are also clearly tied to the question of what it means for Zarathustra to have a teaching, to try to impart it to an audience suffering in this unusual way, suffering from complacency or dead desire. Only at the very beginning, in the Prologue, does he try to ‘lecture publicly’, one might say, and this is a pretty unambiguous failure.

The reminder of the Prologue appears to indicate that Zarathustra himself had portrayed his own teaching in a comically inadequate way, preaching to the multitudes as if people could simply begin to overcome themselves by some revolutionary act of will…

He had shifted from marketplace preaching to conversations with disciples in Part I, and at the end of that Part I he decides to forgo even that and to go back to his cave alone.

As to the latter, I think I should no longer tweet on X (if anyone wants to ask me why, do so in the comments section).

Hitler, 1

Hitler was born on 20 April 1889, i.e. he was a year younger than my paternal grandmother, with whom I lived for a while (that means that if it hadn’t been for the Allied dogs, I might even have met him!). He was born in Braunau am Inn in Austria. Hitler would later call himself a Bavarian on several occasions.

At the beginning of the first part of his book, Brendan Simms informs us that the first three decades of Hitler’s life were characterised by obscurity and various deprivations; his father and mother died, the latter after a traumatic illness, and his artistic talent went unrecognised in Vienna. Those were times, and we are talking before his twenty-fifth birthday, when the young Adolf didn’t yet show any signs of politicisation.

Today I can say that of all the post-1945 writers, I have the closest rapport with Savitri Devi—by far. But before I discovered white nationalism, and I’m talking about how I thought from 2002 to 2009, Alice Miller, the first author in history to take the side of the child abused by his parents was, intellectually, my Beatrice. It’s interesting what Simms says at the beginning of his biography: that there is no evidence that Alois, Hitler’s father, was violent to his children; because Miller, who suffered in the Warsaw ghetto, defamed Hitler by speculating that he had indeed been abused by his father Alois.

Hitler had an older half-brother, Alois Junior, and a half-sister, Angela, born from his father’s first marriage. After the death of his first wife, Alois married his cousin Klara Pölzl, with whom he had six children, only two of whom survived: Adolf himself and his younger sister Paula. Two of Hitler’s four siblings died before they were born, and another when Hitler was ten years old.

At school, the boy Adolf only got good marks in drawing and sport, but he was such a bad student that he failed one year before leaving school for good at the age of sixteen, about the age at which I, too, left school and for the same reasons (it’s all brain-washing bullshit what the System teaches us there). Simms informs us:

Hitler’s main preoccupations after leaving school were his financial security, his emotional life, pursuing a career as an artist and the health of his mother. The first known letter by Hitler was penned in February 1906, together with his sister Paula, asking the Finanzdirektion Linz for payment of his orphan’s pension.

I will be omitting the numbers and endnotes throughout my quotations of Simms’ book.

He visited Vienna on a number of occasions and soon moved to the imperial capital. There he pursued an interest in the operas of Richard Wagner. In the summer of 1906, Hitler saw Tristan and Isolde as well as The Flying Dutchman. He also attended the Stadttheater. He was engrossed by not only the music but especially the architecture of opera. A postcard of the Court Opera House Vienna records that he was impressed by the ‘majesty’ of its exterior, but had reservations about an interior ‘cluttered’ with velvet and gold.

I know that many visitors find it bothersome that, whenever I can, I take the opportunity to denigrate white nationalism. But I must. Savitri hits the nail on the head in her book when she points out that the Hitler phenomenon can only be understood if we see that he was a kind of initiate. And the initiation was art! It seems easy for me to understand this because, coming from parents who were artists, it seems obvious to me that this is what motivated me to seek a different path from the crap that conventional schooling offers us (everything looks like pork to someone who understands Beauty as a child). In other words, if contemporary racialists fail to initiate themselves into art, they won’t be able to save their race. I will not repeat Savitri’s reasons: that is why we abridged her book and translated that abridged version here. Simms continues:

In early 1907, Hitler’s mother was diagnosed with cancer and operated on without success. She had no medical insurance, but bills were kept low by the kindness of her Jewish doctor, Eduard Bloch. Hitler helped to look after his mother during her illness and he seems to have been devastated by her death in late December 1907.

He was eighteen years old.

It is certain, in any case, that Hitler neither blamed Bloch for his mother’s death nor became an anti-Semite in consequence. On the contrary, he remained in friendly contact with Bloch for some time after and even sent him a hand-painted card wishing him happy new year. Much later, Hitler enabled Bloch to escape from Austria on terms far more favourable than those granted for his unfortunate fellow Jews.

The young Hitler’s interests were above all musical and architectural, like the layout and architecture of Linz. He confessed to leading a hermit’s life and was plagued by bedbugs. These were times when he was on good terms with August Kubizek, another teenager. Savitri recounts some very revealing anecdotes of this friendship in her book. Simms ignores them in his biography Hitler, although he writes the following:

He certainly seems to have experienced a period of poverty, telling Kubizek that ‘you don’t have to bring me cheese and butter anymore, but I thank you for the thought’. He was not too poor, however, to miss a performance of Wagner’s Lohengrin.

Shortly, afterwards, Hitler left the Stumpergasse and was swallowed up by the city for more than a year. He lodged with Helene Riedl in the Felberstrasse until August 1909. His only known activity during this period was a second and equally unsuccessful application to the Academy. Hitler then lived for about a month as a tenant of Antonia Oberlerchner in the Sechshausterstrasse, leaving in mid September 1909. Even less is known about what came next. He certainly underwent some sort of economic and perhaps psychological crisis, leading to a descent from respectability.

Der Hauptplatz in Linz

A few years later, well before he was famous, Hitler told the Linz authorities that the autumn of 1909 had been a ‘bitter time’ for him. According to a statement he gave to the Vienna police in early August 1910, he spent a time in a sanctuary for the homeless at Meidling. How Hitler extricated himself is not known, but he was able to pay for a bed at the more respectable men’s hostel in the Meldemannstrasse in Vienna-Briggitenau from February 1910. There he started to paint postcards and pictures which his crony and ‘business’ partner Reinhold Hanisch would sell to dealers; this relationship soured when he reported Hanisch to the authorities for allegedly embezzling some of the money.

Now that I posted a review of The Godfather, I’ve been watching videos about the real-life mafia. One YouTubber said that what these people really loved was the American dollar. Those gangsters were slaves to Mammon, just like Hitler (and I) are slaves to the Goddess of Beauty. Simms ends his first chapter with some of these passages:

All we know for sure is that Hitler had to mark time in the Austro-Hungarian Empire until he was twenty-four so as to keep collecting his orphan’s pension. It did not help that he fell out with his half-sister Angela Raubal over their inheritance, and was forced to give way after a court appearance in Vienna in early March 1911…

In the spring of 1913, Hitler collected the last instalment of his pension. There was nothing to keep him in Vienna. When Hitler went to Munich in May 1913 his worldly possessions filled a small suitcase…

He lived happily for nearly a year under the roof of Czech spinster, Maria Zakreys, and betrayed no irritation at her limited command of German. His documented interests were architecture, town planning and music, particularly the connections between them. There was surely much more going on inside his head, but we cannot be certain what it was.

Hitler’s self-description varied, but the common denominator was creativity. He registered himself as an ‘artist’ in the Stumpergasse in mid February 1908, as a ‘student’ in the Felberstrasse in mid November 1908, as a ‘writer’ in the Sechshausterstrasse in late August 1909, and as a ‘painter’ at the Meldemannstrasse in early 1910 and again in late June 1910…

He was eventually mustered in Salzburg by the Austrian authorities, in early February 1914, and found to be physically unfit to serve. In the meantime, Hitler continued to make his living by selling pictures, just as he had in Vienna.

All this makes our picture of the young Hitler closer to a sketch than a full portrait. To be sure, he was already more than a mere cipher: his artistic interests were already well established; his hostility to the Habsburg Empire, though not the reasons for it, was a matter of record… There is no surviving contemporary evidence that he was much aware of France or the Russian Empire or the Anglo-World of the British Empire and the United States. That was about to change. If the Hitler of 1914 had as yet left almost no mark on the world, the world was about to make his mark on him.

The Godfather

Marlon Brando (right) and Al Pacino as Don Vito and Michael Corleone.

Marlon Brando (right) and Al Pacino as Don Vito and Michael Corleone.

It could be said that in recent times I have taken my vows as a priest of the sacred words, in the sense that being an NS ideologue after 1945 implies constant activity for the cause, and never allowing myself to burn out, and I plan to live like that until death parts me from this world.

But more than an act of will, when one begins the lifestyle of a true NS (which to distinguish it from the pre-1945 Germans I call the priesthood of the sacred words, after the priestess Savitri Devi) the mind begins to metamorphose.

I have often said that when I was younger I wanted to be a film director. And indeed, I have seen a lot of cinema over the decades. But when I heard about the West’s darkest hour, in the sense that it occurred to the Aryan to commit ethnic suicide because of what I said about the new Sacrificial Lamb at midnight, my taste for the Seventh Art began to change. Films I had loved I began to see as containers of very bad messages: part of the brainwashing process to convince the Aryan to immolate himself.

When I took my vows, so to speak, I began to realise not only that I was beginning to detect those bad messages, but that I could no longer enjoy almost any film in my DVD collection, to the extent that I recently gave my nephew my big TV, where I used to watch films. I did this because a lot of times it occurred to me to go through the titles of my DVD collection and, to my surprise, I didn’t feel like watching almost any film again.

At the time of the COVID-19 epidemic, a European asked me what my favourite films were at the time, and I made a list of fifty of them. A few years later I can no longer watch most of them! It’s amazing how taking vows gradually, but forcefully, changes a priest’s tastes.

But given my past fondness for cinema, and that I spent so much time watching films and thinking about them, it occurs to me that I could start writing short reviews of each film on my list of fifty. But I’d like to start with one that doesn’t appear on the list, The Godfather.

______ 卐 ______

Once upon a time in the US the Western was the favourite film genre for family consumption, but with time it was replaced by the mob story as the central epic of America. The Godfather is considered the best film of this genre. Some fans of American cinema even consider it the best film made in that country, even ahead of Citizen Kane. Well, below we see a brief review from the point of view of National Socialism, or rather, the POV of the priest of the sacred words.

Taking into account what we say in this post about transvaluation (‘L’art pour l’art’ values must be transvalued to Art practised in conformity with the cultural task), the message of The Godfather couldn’t be more wrong. Michael Corleone is the antithesis of what the hero of an Aryan lad who goes to the movies to have fun should be. In fact, the fictional Michael Corleone is an enemy of the sacred words. There is a scene in which the capo Clemenza teaches Michael how to shoot and casually tells him that Hitler should have been stopped before the time when the Allies finally stopped him. Remember that the film opens in 1945, when Michael is dressed in a soldier’s uniform at his sister’s wedding because, decorated, he had just returned from fighting the Germans!

That alone would be enough to ban The Godfather in an ethnostate emerging in North America. But it doesn’t end there. Francis Ford Coppola, the director, is Italian-American and his film represents the interests of his ethnic group, not those of the Anglo-Germans who originally conquered and populated the US (see e.g., what I wrote ten years ago about The Godfather Part II). In an ethnostate that imitated the Third Reich only the Nordics, or fans of the Nordics (say, like me), would be allowed to practice art in conformity with the NS task. It is absurd that someone who represents the interests of another ethnic group should have cinematic power over the youth of Nordic stock, and this is even more so in the case of the Jewry that dominates Hollywood.

As you can see, from this angle the reviews that I could write about American cult films are the antithesis of what Trevor Lynch (Greg Johnson) does in Counter-Currents. But as we have said many times, from the NS POV white nationalism (WN) is intellectual quackery for people stuck in the middle of what we call the psychological Rubicon (cf. my featured post, ‘The River Nymph’).

There are many other things I could say about the Godfather trilogy. For example, Moe Greene, who is shot in the eye by Michael’s triggerman at the end of the first film while being massaged, in Mario Puzo’s novel is a Jewish gangster. So in the sequel Michael’s rival, the Jew Hyman Roth, wants to avenge him. In other words, for political correctness in the Godfather trilogy the tension between the Italian-American mafia and the Jewish-American mafia is more or less disguised.

I was also annoyed, but this is natural since the director is Italian-American, that the viewpoint of the family of Kay Adams Corleone, Michael’s second wife, a pure Aryan, was one hundred per cent absent. If one compares her with the Sicilian Apollonia Vitelli Corleone, Michael’s first wife, one can see the difference between a Mediterranean and a Nordic.

Keep in mind that when the SS invaded the USSR, the commanders were careful that the young soldiers didn’t marry mudblood women (remember: when we were young we thought with our cocks, not with our heads!). That distinction between Meds and Norsemen has been lost on many contemporary racialists because, I reiterate, WN is virtually intellectual quackery.

These brief words give an idea of what, in forthcoming posts, I will do with most of the 50 films I used to recommend a few years ago. When the priest fulfills the revaluation of art (‘L’art pour l’art’ values must be transvalued to Art practised in conformity with the cultural task) there is very little art to rescue—and much art to repudiate!

National Socialism

and the Laws of Nature

by Martin Kerr

“…It is Life alone that all things must serve.”

—Adolf Hitler, Mein Kampf, Vol. I, Chap. 9, p. 215 (Manheim)

INTRODUCTION

A unique and compelling feature of the National Socialist worldview of Adolf Hitler is that, of all the various political movements and ideologies of the modern era, it alone is based solely on the Natural Order. Only National Socialism is grounded in reality, and not in phantasms of human mind.

National Socialists believe that the universe is governed by natural laws, and that for Man to be happy and successful, he must first acknowledge that these laws exist; secondly, he must discover what they are; and thirdly, he must live in accordance with them. This is another way of saying that the universe runs according to the principles of Causality—that is, of cause-and-effect relationships—and that it does not operate on the basis of supernatural forces, or on the mental constructions and wishful thinking of intellectuals and ideologues, or on the religious fantasies of theologians.

Hitler made this clear from the beginning of his career in public life. Writing in his book Mein Kampf in 1924, he stated:

When Man attempts to rebel against the iron logic of Nature, he comes into struggle with the principles to which he himself owes his existence as a man. And so his action against Nature must lead to his own doom… Here we encounter the objection [that] ‘Man’s role is to overcome Nature!’… But Man has never yet conquered Nature in anything, but at most has caught hold of and tried to lift one corner or another of her immense gigantic veil of eternal riddles and secrets, that in reality he invents nothing but only discovers everything, that he does not dominate Nature, but has only risen on the basis of his knowledge of various laws and secrets to be lord over those other living creatures who lack this knowledge… (Vol. I, Chap. 11, Manheim trans., p. 287)

And elsewhere:

Man must never fall into the madness of believing that he has risen to be lord and master over Nature—which is so easily induced by the conceit of half-education—but must understand the fundamental necessity of Nature’s rule, and realize how much of his existence is subject to these laws of combat and upward struggle. Then he will sense that in a universe where planets revolve around suns, and moons turn around planets, where force alone forever masters weakness, compelling it to be its obedient servant or else crushing it, there can be no special laws for Man. For him, too, the eternal principles of this ultimate wisdom hold sway. He can try to grasp them, but escape them never. (pp. 244-245)

The goal of National Socialism, then, is to consciously organize human society in accordance with the Natural Order. The postwar Danish National-Socialist Povl H. Riis-Knudsen thus defined National Socialism in a single sentence: “National Socialism is the application of the Laws of Nature to human affairs.”

The dominant thought-systems of today are uniformly based on the notion of human equality in one form or another: Multiracialism on racial equality; Marxism on economic equality; democracy on political equality; Christianity on spiritual equality. But when Adolf Hitler observed the world of living Nature, he saw that it was not equality, but rather inequality, that was ever-present. To be more precise, he saw that Nature operated according to the principles of structure and hierarchy.

There is structure and hierarchy both among the races of mankind, and also within the races. The hierarchy among the races he denoted as the Principle of Race, and that within each race as the Principle of Personality. He discusses this in depth in Volume II, Chapter 4, of Mein Kampf.

In a speech given in 1928, Hitler gave his own one-sentence definition of the National Socialist worldview: “All life is bound up in three theses: struggle is the father of all things, virtue lies in the blood, and leadership is primary and decisive.” Here “blood” symbolizes the Principal of Race and “leadership” the Principle of Personality. “Struggle” is the mechanism by which position in the hierarchy is determined.

The belief that life should be lived in harmony with the Natural Order permeated the whole of Hitler’s Germany, from the top to the bottom. It manifested itself not just in the political structure of the National Socialist state, but in every facet of society, including child-rearing, nutrition, forestry, animal rights, medicine and healthcare. The protection of the environment was a top priority. Truly, National Socialism was the original “green” movement!

The SS had a popular motto: “Know the laws of life and live accordingly.” Another SS saying pointed to the spiritual dimensions of the National-Socialist worldview: “The Divine manifests itself in the order of Nature, not in supernatural miracles.”

The scientific community enthusiastically supported the restructuring of society in harmony with the Natural Order. One example of this was botanist Ernst Lehmann, who characterized National- Socialism as “politically applied biology.” In 1934, only one year into the NS era, he wrote:

We recognize that separating humanity from Nature, from the whole of life, leads to mankind’s own destruction and the death of nations. Only through a reintegration of humanity into the whole of Nature can our folk be made stronger. That is the fundamental point of the biological tasks of our age. Mankind alone is no longer the focus of thought, but rather life as a whole… This striving with connectedness, with the totality of life, with Nature itself, a Nature into which we are born, this is the deepest meaning and the true essence of National-Socialist thought. (Biological Will: Means and Goals of Biological Work in the New Reich, pp. 10-11)

It is easy for the unsuspecting or the misinformed to fall victim to the vicious, lying, Hitler-bashing, anti-NS propaganda that is everywhere today. Attempts to discuss the profound and life-giving character of Adolf Hitler’s National Socialism often get sidetracked and bogged down in ridiculous and ill-informed debates concerning the conduct of German military operations during the Second World War—as though that subject were more important than our survival as a race!

But one person saw clearly through the miasma of anti-Hitlerism even when it was at its height. The National Socialist philosopher Savitri Devi recognized the magnitude of Adolf Hitler’s achievements, and of the unique value of his teachings—not just to the Aryan race, but to all mankind. In her magnum opus The Lightning and the Sun (1958) she wrote:

In its essence, the National Socialist idea exceeds not only Germany and our time, but the Aryan race and mankind itself and any epoch; it ultimately expresses that mysterious and unfailing wisdom according to which Nature lives and creates: the impersonal wisdom of the primeval forests and of the ocean depths and of the spheres in the dark fields of space; and it is to Adolf Hitler’s glory not merely to have gone back to that divine wisdom … but to have made it the basis of a practical regeneration policy of worldwide scope … (The Lightning and the Sun, pp. 219-220, standard edition; p. 128, Pierce edition)

We live in a civilization and in a society that is about as divorced from the Natural Order as possible. That is why the our race is sick. That is why the our race is dying. Only by once again living in harmony with the Laws of Nature can we regain our racial health. There is only one movement which offers this salvation, and hence there is only one path to racial survival, that of Adolf Hitler and National Socialism.

A SOCIOBIOLOGICAL PERSPECTIVE

Sociobiologists divide the animal world into three broad categories, based on whether or not they live in societies, and if they do, their degree of socialization. Animals which live in societies live in groups characterized by (1) hierarchy, and (2) cooperation. The three categories are:

1. Asocial animals, which either live solitary lives as individuals or else they live in groups without hierarchy or cooperation. Most felines (except for the lion) and orangutans are examples of animals who live as individuals. Schools of fish, flocks of birds and Thompson’s gazelle are animals who live in groups that are unstructured and the members of which do not cooperate with each other—basically they are collections of individuals.

2. Eusocial animals (essentially, bees, ants and their relatives) live in communities in which the individual does not exist for practical purposes—only the collective exists.

3. Social animals live in groups known as societies, in which there is hierarchy and cooperation. The individual has rights, but the rights generally are subordinate to the welfare of the society. Most higher primates, including all of the great apes except for the orangutan, and most canines, are social animals. Human beings are social animals. We are not bees (for whom only the collective exists) and we are not tigers (for whom only the individual exists).

In human society, the individual has rights, but these must be balanced against the overall welfare of the group. There is inevitably some tension between the group and the individual, but in successful societies this it is managed so that neither suffers unduly.

National Socialist Germany is the modern society that has done this the best. As a social state, it stands in balanced mid-point between the hive-like, eusocial collectivism of communism (in which the individual exists only to serve the state, and who has no rights at all), and the rootless, naked egoism of asocial libertarianism (in which the good of the whole is subordinate to the desires and whims of the individual).

This balance between the desires of the individual and the good of the racial community is exemplified in the Hitlerian dictum, “The right to personal freedom recedes before the duty to preserve the race.” (Mein Kampf, p. 255). This statement explicitly recognizes that there is a right to personal freedom, but that this right is subordinate to the common racial good.

The word “natural” is only problematic if someone is determined to see it as so. The opposite is “artificial.” The wolf is a canine that is the product of natural selection. The Chihuahua is a canine that is product of artificial selection. The society we live in today is an artificial society that is divorced from Nature. To be healthy as a race, we need a society that is structured in accordance with the world of Nature.

THEORY AND PRACTICE

Writing in 1980, the brilliant Australian National Socialist Dr. E.R. Cawthron, B.Sc. (Hons), noted that, “Just to speak in general terms about the laws of Nature serves little purpose.” Very true! Let us take a look at a specific natural law and its concrete application in National Socialist Germany.

In the above Introduction, it was noted that Adolf Hitler recognized that inequality, not equality, was the norm in living Nature, and that with regard to Man, this inequality manifested itself both between the races, and within each race. As a corollary to the law of racial inequality, Hitler also discerned a law concerning “the urge toward racial purity.” He wrote:

[M]en without exception wander about in the garden of Nature; they imagine that they know practically everything and yet with few exceptions pass blindly by one of the most patent principles of Nature’s rule: the inner segregation of the species of all living beings on this earth…Every animal mates only with an animal of the same species… Only unusual circumstances can change this… (p.284)

He further noted:

The result of all racial crossing is therefore in brief always the… lowering of the level of the higher race. (p.286)

And he offered an example:

Historical experience shows countless proofs of this. It shows with terrifying clarity that in every mingling of Aryan blood with that of lower peoples the result was the end of the cultured people. North America, whose population consists in by far the largest part of Germanic elements who mixed but little with the lower colored peoples, shows a different humanity and culture from Central and South America, where the predominantly Latin immigrants often mixed with the aborigines on a large scale. By this one example, we clearly and distinctly recognize the effect of racial mixture. The Germanic inhabitant of the American continent, who has remained racially pure and unmixed, rose to be the master of the continent; he will remain the master as long as he does not fall victim to defilement of the blood. (p. 286)

Thus we can see the development of Hitler’s logic with regard to natural law in this instance:

• He begins by postulating a law or principle that holds true for all of living Nature.

• He further shows how Man is specifically included in this law’s

• Taking the discussion out of the realm of theory, he gives a concrete example of the expression of this law in the real world.

But it does not stop there. On September 15, 1935, Adolf Hitler, as chancellor of the German Reich, signed a law into effect prohibiting race-mixing between “citizens of German or related blood” and Jews. This act was formally titled the “Law for the Protection of German Blood and German Honor.”

Mainstream historians have termed this the “Nuremberg Race Law,” and claimed that it was the sinister first step toward the extermination of European Jewry. But it was nothing of the sort. Rather, it was a preliminary and far-sighted attempt to tentatively codify Natural Law as State Law. Adolf Hitler had begun to restructure German society so as to bring it in accordance with Nature—just as he had advocated a decade earlier in Mein Kampf.

LINCOLN ROCKWELL’S ‘LAWS OF THE TRIBE’

George Lincoln Rockwell is the founder of postwar American National Socialism, and one of the foremost disciples of Adolf Hitler’s thought of all time. He is remembered primarily as a man of action, which is unsurprising given the dramatic and dynamic course of his life. Yet he was also a man of towering intellect. In addition to numerous essays and articles, he authored two books, This Time the World (1962), his political autobiography, and White Power, which was published posthumously in 1968.

Like Adolf Hitler, Lincoln Rockwell recognized that Man was a part of the Natural Order, and that he was in no meaningful way separate or distinct from it. In Chapter 15 of White Power, entitled “National Socialism,” he lists five “Laws of the Tribe” that govern the social organization of all social animals (see Part Two). They are true for wolves as well as for elephants, for dolphins as well as for chimpanzees—and for Man as well. In a human context, by “Tribe” Rockwell means Race or folk or ethnicity.

Here are Rockwell’s Five “Laws of the Tribe”:

1, The Law of Biological Integrity;

2. The Law of Territory;

3. The Law of Leadership;

4. The Law of Status; and

5. The Law of Motherhood or Family

In White Power, he discusses four of the five principles or laws in some depth. By Biological Integrity, Rockwell means both the instinctive urge to protect the exclusive gene-pool of the tribe, but also the love-hate dichotomy that this generates. He writes:

The two instincts are equally important. Love is not “good” while hate is “evil” — which is the canard so dearly loved by the Jews, liberals, hippies, queers, and half- wits…

Love, the natural healthy kind, is indeed what makes the world go round, and it is the most beautiful, holy miracle we ever see here on earth.

But without a deadly hate of that which threatens what we love, Love is an empty catchword for hippies, queers, and cowards…

Biological Integrity: absolute, total and uncompromising loyalty to one’s own racial group based on a consuming love, and absolute, uncompromising hatred of any outsiders who intrude and threaten to mix their genes with those of the females of the group. (pp. 445-446)

By “Territory” he means in the first instance the land or real estate that the tribe lives on. In National Socialist Germany, the close relationship between Biological Integrity and Territory was encapsulate in the phrase “Blood and Soil” (Blut und Boden). But he also expands this to include the principle of private property. Here Rockwell draws a fundamental dividing line between National Socialism and Jewish, Marxist socialism.

Rockwell specifies “Leadership by the best.” By the best, not by the most popular, nor by the wealthiest, and certainly not by those most eager to kiss Jewish posterior.

“Status” he defines as the natural place or rank of each individual within the tribe. Everyone in the tribe is not “equal” to everyone else—but each person has worth and value, and a role to play in society.

Rockwell does not mention Motherhood and Family, beyond including it in his list of Five Laws. He was writing in the mid-1960s, when everyone in White society still had a healthy appreciation of the traditional family. He apparently thought that it was unnecessary to describe it further. Perversions such as homosexual “marriage” were so far over the social horizon that they were not even visible in 1967. One can only imagine what he would have to say about such manifestations of racial decadence and social decline. The traditional family always has been, remains, and always will be the basic social building block of every healthy White society.

Rockwell was not a trained anthropologist, and in listing the Five Laws, he was deeply indebted to Robert Ardrey, author of books on this subject such as African Genesis and The Territorial Imperative. But although it was outside the field of his formal knowledge, Rockwell was intelligent enough to recognize the truth when he saw it, and to portray it from a National Socialist perspective.

When he first read African Genesis, Rockwell was so taken with Ardrey’s ideas that he wrote the author a multipage letter explaining that National Socialism was nothing less than the political embodiment of Ardrey’s central thesis. When several months passed and the author did not respond to his communication, Rockwell sent him a registered letter asking if he had received his first letter. Again, Ardrey did not reply.

However, Ardrey went on to write another book, The Territorial Imperative, in which he discussed his Law of Territory in detail. In this book, Ardrey takes pains to explicitly distance himself from National Socialism. He does not mention Rockwell by name, nor does Ardrey address Rockwell’s contention that National Socialism is the political embodiment of his ideas—he just wants his readers to know that he was not one of those awful “Nazis.”

Nonetheless, both African Genesis and The Territorial Imperative are great books, and their content is completely NS in their exposition. We recommend both, despite the superficial anti-NS orientation of the second volume.

These Five Laws enunciated in White Power will someday form the basis for the National Socialist New Order which we, the heirs of Hitler and Rockwell, will build in North America.

CONCLUSION

The question that White people must ask themselves is this: Does human existence rest on a biological foundation or not? If it does, then the biological prerequisites that form the basis of our existence must be respected or a great price for ignoring them must be paid.

The wages of racial sin is racial death.

The situation today, in which the Aryan peoples of the world—without exception—live in societies completely divorced from the Natural Order must be viewed from a great historical perspective as a temporary dislocation. It is a sickness, not a permanent condition, and the patient will either recover or die.

National Socialism is the reorientation of human society to once again bring it in accordance with Nature and her iron laws. It is the cure for the disease.

NATIONAL SOCIALISM AND THE NATURAL ORDER: A SELECT READING LIST

What I have written here is only an introduction to the topic of National Socialism and the Natural Order. To really grasp it thoroughly and in depth, it needs to be studied. Here are a few texts to get you started on your exploration.

Basic National Socialist texts

- Mein Kampf by Adolf Hitler. Verlag Franz Eher Nachfolger, GmbH, Muenchen, Band I 1925, Band II 1927, 781 pp., index.

- Mein Kampf by Adolf Hitler, trans. Ralph Manheim. Houghton Mifflin Company, 1943. Index, 694 pp., ISBN-13: 978-0395925034. Reading it the original is always the preferred option, but if you are limited to an English translation, this one is the best.

- White Power by George Lincoln Rockwell. Ragnarok Press, Dallas, Texas, 1967 [1968]. Illustrated, 482 pp. See especially Chapter 15, “National Socialism,” for Rockwell’s discussion of the Natural Order and National Socialism.

- National Socialism: The Biological Worldview by Povl H. Riis-Knudsen. Nordland Forlag, Aalborg, 1987. Frontispiece, 30 pp. Essential.

Books hostile to National-Socialism but still containing valuable information

- Blood and Soil: Walther Darré and Hitler’s Green Party. Kensal Press, 1985, 224 pp., ISBN-13: 978-0946041336. Not pro-NS by any stretch of the imagination, but much less hostile than most mainstream books on Hitler and the Hitler era.

- Racial Hygiene: Medicine under the Nazis by Robert N. Proctor. Harvard University Press, Cambridge, Mass., and London, England, 1988. Notes, index, bibliography, 43 figures, 414 + vii pp., ISBN 0-674-74580-9. See especially Chapter 1, “The Origins of Racial Hygiene,” and Chapter 3, “Political Biology: Doctors in the Nazi Cause.” Proctor goes out of his way to show that he is anti-NS, perhaps because the subject he investigates are so inherently pro-NS.

- The Nazi War on Cancer by Robert N. Proctor. Princeton University Press, Princeton and Oxford, 1999. Notes, index, bibliography, figures, 380 + x pp., ISBN 0-691-00196-0. See especially Chapter 3, “Genetic and Racial Theories,” Chapter 5, “The Nazi Diet,” and Chapter 6, “The Campaign against Tobacco.” Even more hostile than Racial Hygiene — but containing even more good information.

- Ecofascism: Lessons from the German Experience by Janet Biel and Peter Staundenmaier. AK Press, San Francisco and Edinburgh, 1995. Footnotes, 73 pp., ISBN 1-873176-73-2. Consists of two essays: “Fascist Ideology: the ‘Green Wing’ of the Nazi Party and Its Antecedents” by Staudnemaier; and “‘Ecology’ and the Modernization of Fascism in the German Ultra-Right” by Biehl.

Anthropology and sociobiology

None of the books listed below is written by a National-Socialist or with an NS or WN audience in mind, but they all show the biological underpinnings of the National Socialist worldview and NS policies.

- Introduction to Anthropology by Dr. Roger Pearson. Harcourt College Publishers, 1974. Approx. 500 photographs, charts, and maps; glossary; table of languages; index, 616 pp., ISBN-13: 978- 0030915-17-8.

- Sociobiology: The Abridged Edition by Edward O. Wilson. Harvard University Press, Cambridge, Mass., and London, England, 1980. Bibliography, glossary, index, 366 + ix pp., ISBN 0-674-81623-4. There is a longer version, Sociobiology: The New Synthesis, written for scholars, but we recommend the abridged edition for non-specialist readers.

- Promethean Fire: Reflections on the Origin of the Mind. Charles J. Lumsden & Edward O. Wilson, Harvard University Press, Cambridge, Mass., and London England. Endnotes, index, 216 pp., ISBN 0-674-71445-8.

- African Genesis: A Personal Investigation into the Animal Origins and Nature of Man by Robert Ardrey, Atheneum Publishers, NY, 1961. Paperback edition, 384 pp., index, ISBN 0-553- 10215-X.

- The Territorial Imperative: A Personal Investigation into the Animal Origins of Property and Nations by Robert Ardrey, Atheneum Publishers, NY, 1966. Bibliography and bibliographical key, 355 pp.

- The Naked Ape: A Zoologist’s Study of the Human Animal by Desmond Morris. ISBN 0- 070431-74-4, 1967. Says Wikipedia: “[Z]oologist and anthropologist Desmond Morris… looks at humans as a species and compares them to other animals. The Human Zoo, a follow-up book by Desmond Morris, which examined the behavior of people in the cities, was published in 1969.”

- Race by John R. Baker. Oxford University Press, London, 1981, ISBN 0-936396-01-6. 625 pp., 13 appendices, 82 illustrations, bibliography. A comprehensive, exhaustive examination of the biological reality of race and racial differences. Suitable both for specialist and general readership.

Comments

I would like to offer my comments on the Kerr article I reproduced this morning, ‘The National Socialist lifestyle’:

But to be a true National Socialist in a profound sense means living an NS lifestyle, not just to agree with NS ideas in an abstract manner, or to admire historical National Socialism from a distance. Hermann Göring once noted that one does not become a National Socialist simply as a matter of intellectual endorsement, but rather that one is born a National Socialist.

This is so true that I cannot resist the temptation to translate some passages of El Grial into English. The words in square brackets mean words that replace the original text to avoid explanatory notes (as these decontextualised passages already appear on pages 99-100 of my third autobiographical book). I will use blue to distinguish it from the indented quotes in Kerr’s article:

It should not be speculated that my mistreatment at home is the primary cause of my now wanting to wipe Neanderthals off the face of the earth. Many years ago [my sister] told us the anecdote of something that I don’t remember well but which, I am sure, her memory is genuine. She said that, when I was eleven years old, I had made [exterminationist pronouncements from the racial POV].

Although I barely remember it, I do remember that as a child the spectacle of visiting the centre of the metropolis caused me such horror that I wanted to sweep it all away. And even younger, perhaps nine or ten years old when Japanese Godzilla films became fashionable, I imagined, lying in bed at bedtime, my favourite monster destroying the street billboards because they degraded my sense of aesthetics. Once I told cousin Julio about this fantasy, which was more ethical than anything else, in the sense of destructive justice, with ‘Godzilla’ being the judge of the degraded society.

Later, in my puberty, I wondered why there were still other races if it was so obvious that the white race was so superior. It was an inner feeling that told me something like: why are they still here? I didn’t understand why the non-white lands hadn’t already been conquered.

One of the most beautiful memories I have, because it dates back to the time when my life was still innocent, [already in my teens], was when I once went to get my hair cut at the hairdresser’s closest to my house, on Doctor Vértiz Avenue, with one of my younger brothers. It was a very serene afternoon while I was waiting my turn when I saw, in the illustrated stories on the hairdresser’s table, one that presented in pictures the goals of Germany a few decades ago. What stuck very clearly in my mind was the information that it was about producing a line of beautiful blond Aryans with blue eyes. It felt very good to me because those were things I wanted, even though I had never seen them enacted in the written word, even if it was in the drawings of a comic book. In retrospect, I suppose that story had not been illustrated or written by a fan of National Socialism, but to my adolescent mind, what mattered was that someone expressed an ideal that seemed to me so lofty and noble: something I hadn’t heard articulated as openly as on that gentle afternoon, which I still recall with nostalgia today.

The above happened in Mexico City, which is hardly an Aryan town! Kerr’s text continues:

As Adolf Hitler wrote, “Obstacles exist to be broken, not to be surrendered to.” Lincoln Rockwell said that “Life is struggle,” and that the secret to having a happy and successful life was, “to enjoy the struggle.” This is the fundamental NS attitude towards life in general.We welcome struggle, not as a necessary evil, but as a great gift and opportunity that allows us to strengthen ourselves mentally, physically and spiritually. Again quoting Hitler: “Mankind has grown great in eternal struggle, and only in eternal peace will it perish.”

This is what the defeatists and pessimists don’t understand and why I no longer take nationalist forums seriously. It is about fighting morning, noon and evening for the sacred words (as far as I am concerned, to change the paradigm from JQ to CQ, because if the problem lies with us, that would empower us immensely). Kerr continues:

[A] National Socialist gets out and engages in the real world. This may take the form of participating in a public activity to build the Movement, or it may simply be going for a hike in the forest. Citing an old Aryan adage, the Führer noted that, “he who rests—rusts” (Wer raset, der rostet). Do you take the escalator or the stairs? Said Mussolini, “The fascist distains the easy life.” The Duce was not a National Socialist, but in this instance his words are consistent with an NS lifestyle.

Without dropping names, reading this passage brought to mind one of the main promoters of white nationalism in the neighbouring country to the north, who has chosen the bourgeois life.

Every National Socialist accepts the SS saying, “Know the laws of life and live accordingly,” as his or her personal motto.

As a teenager I was enchanted by Seneca’s words, ‘Live according to Nature’!

Consequently, exercise, healthy eating, and nourishing the spirit are key features of an NS lifestyle. Just as laziness is un-National Socialist, so is a diet that consists of processed food, nutritionless (or even harmful) snacks, all washed down with some form of alcohol or a sugar-laden soft drink. Instead, a National Socialist lifestyle includes plenty of fresh fruits and vegetables, with as little meat as possible, along with plenty of water and sunshine. He nourishes his soul with Aryan music and art.

For some time now I have chosen the whole food plant based diet as my diet, and I refine it more every day.

Likewise, the National Socialist shuns polluting himself with the degenerate byproducts of an un-Aryan popular culture. These include films that insult the history of the White race, that promote race-mixing, that degrade women or that glorify crime, as well as so-called “music” that offends the Aryan spirit. Likewise, the National Socialist does not contaminate his body and weaken his spirit with drugs and intoxicants.

Again, without dropping names, this reminds me of the huge number of non-NS racialists who talk about movies, pop music, who recommend eating meat or who don’t love Nature to the extent of deifying it, as I have felt since I was a child to the extent that, when I discovered the painter Maxfield Parrish, I knew that this was exactly what I had had inside me for a long time!

The National Socialist lifestyle includes the love of animals, and kindness towards them. Nothing is so foreign to the Aryan spirit than the sadistic slaughter of animals for food practiced by the Semitic peoples.

This is one of the reasons why those who endorse cruelty to animals (or children) are no longer allowed to comment on this forum.

So even when it is difficult—indeed, even dangerous—he lives his outer life in accordance with his inner being. Yet whatever the cost, he has the great recompense of living his on his own terms. Even in the midst of racial decay and social decline, he lives in the New Order.

And this is exactly what Savitri, my ‘river nymph’ called the Religion of the Strong in the first chapter of her memoirs.

The NS lifestyle

What does it mean to be a National Socialist?

Certainly, we can say that someone who is in general agreement with the National Socialist worldview, as he or she understands it, is a National Socialist in a formal sense of the term. There are also those who appreciate the NS period in European history, although they may not have a comprehensive ideological understanding of National Socialism. They may be described as being sympathetic to National Socialism, even if their theoretical knowledge of the NS worldview is incomplete.

But to be a true National Socialist in a profound sense means living an NS lifestyle, not just to agree with NS ideas in an abstract manner, or to admire historical National Socialism from a distance.

Hermann Göring once noted that one does not become a National Socialist simply as a matter of intellectual endorsement, but rather that one is born a National Socialist. The NS philosopher Savitri Devi further expanded on this idea:

One does not become a National Socialist. One only discovers, sooner or later, that one has always been one—that, by nature, one could not possibly be anything else. For this is not a mere political label; not an ‘opinion’ that one can accept or dismiss according to circumstances, but a faith, involving one’s whole being, physical and psychological, mental and spiritual: ‘not a new election cry, but a new conception of the world’—a way of life—as our Führer himself has said.

It follows that if being a National Socialist is more than just a political belief, it should condition the way one lives one’s life—that is, that there is a characteristic NS lifestyle. Colin Jordan wrote than a person, “acts as a National Socialist, if he is really and entirely one.”

The first thing that we should point out is that a National Socialist has a positive, “can-do” state of mind. He focuses on the solution to a problem, rather than on the problem itself or on the roadblocks that stand in the way to solving the problem. As Adolf Hitler wrote, “Obstacles exist to be broken, not to be surrendered to.” Lincoln Rockwell said that “Life is struggle,” and that the secret to having a happy and successful life was, “to enjoy the struggle.” This is the fundamental NS attitude towards life in general.

We welcome struggle, not as a necessary evil, but as a great gift and opportunity that allows us to strengthen ourselves mentally, physically and spiritually. Again quoting Hitler: “Mankind has grown great in eternal struggle, and only in eternal peace will it perish.” Fritz Kuhn, leader of the German-American Bund in the 1930s, said, “We must welcome every fight!”

Embracing the struggle-ethic to the fullest has two corollaries. The first of these is that the National Socialist enthusiastically leads an active life. Idle complaint is not National Socialist, nor is sitting around and watching television or fiddling with electronic gadgets hour after hour, day after day. Rather, a National Socialist gets out and engages in the real world. This may take the form of participating in a public activity to build the Movement, or it may simply be going for a hike in the forest. Citing an old Aryan adage, the Führer noted that, “he who rests—rusts” (Wer raset, der rostet).

Do you take the escalator or the stairs? Said Mussolini, “The fascist distains the easy life.” The Duce was not a National Socialist, but in this instance his words are consistent with an NS lifestyle.

The second corollary to embracing an active life is that one accepts a heroic, courageous attitude towards existence and death. A National Socialist knows that there are dangers and hardships in the world, that there is pain, and that someday we all die. Rather than becoming depressed by such a realization, or retreating from the world in a cowardly manner, the National Socialist greets life with joyous fortitude. He steels himself mentally, physically and spiritually against the hardships that he may encounter, with absolute determination to fight through them with manly defiance. The National Socialist resolves to die with a cry of triumph on his lips, not to pass away cowering and whimpering like a beaten dog.

Every National Socialist accepts the SS saying, “Know the laws of life and live accordingly,” as his or her personal motto.

Consequently, exercise, healthy eating, and nourishing the spirit are key features of an NS lifestyle. Just as laziness is un-National Socialist, so is a diet that consists of processed food, nutritionless (or even harmful) snacks, all washed down with some form of alcohol or a sugar-laden soft drink.

Instead, a National Socialist lifestyle includes plenty of fresh fruits and vegetables, with as little meat as possible, along with plenty of water and sunshine. He nourishes his soul with Aryan music and art.

Likewise, the National Socialist shuns polluting himself with the degenerate byproducts of an un-Aryan popular culture. These include films that insult the history of the White race, that promote race-mixing, that degrade women or that glorify crime, as well as so-called “music” that offends the Aryan spirit. Likewise, the National Socialist does not contaminate his body and weaken his spirit with drugs and intoxicants.

A while back someone posting on Stormfront claimed that his favorite music was “National Socialist rap.” Let us get this straight once and for all: there is no “National Socialist rap,” nor is there “NS hip-hop” or “Aryan jazz.” We do not insist that 14-year-old Aryan girls forego silly love songs and listen only to Luftwaffe assault marches or German opera—only that Aryans of both sexes and all ages nourish their spirits with musical forms that are produced by, and consistent with, their racial souls.

In so far as possible, the National Socialist lifestyle is family oriented. Just as he views his race as a gigantic extension of his family, so he views his family as his race in miniature. The National Socialist man treats the women and children of his race with respect, dignity and affection. His fundamental attitude towards them is protective and supportive, not hostile and aggressive.

Sadly, many teenage National Socialists living in a non-NS household alienate themselves from their families by attempting to convert their parents to the Hitlerian worldview over Sunday dinner. Tensions between National Socialists and non-National Socialists within a given family are inevitable, but it is the duty of the National Socialist not to let these tensions rend the family apart. Save your efforts at spreading the Good Word to those outside your family. Explain your beliefs if asked, but do not push them on family members.

National Socialists spend as much time outdoors as they can. They garden, go for walks in the woods, and generally enjoy the splendor of living Nature. They feel that they themselves are a part of the natural world, not that it is a foreign environment they visit on rare occasion.

The National Socialist lifestyle includes the love of animals, and kindness towards them. Nothing is so foreign to the Aryan spirit than the sadistic slaughter of animals for food practiced by the Semitic peoples.

A true National Socialist interacts with the non-Aryans he encounters in his daily life in a courteous manner, to the degree that they treat him the same. Whatever hostility that we may feel towards other peoples is not personal, and it should not be taken out on random non-Whites whom we may encounter. The depiction of National Socialists as being rude, mean or insulting to ordinary non-Whites, who have done nothing offensive, is right out of the Jewish playbook. Despite what our enemies may say about us, the National Socialist is not a mindless thug.

It is not always easy to live an NS lifestyle in today’s world. Certainly, it is easier in all-White rural areas than it is in the soulless racial cesspools which our cities have become.

In the first decades of the 20th century, Adolf Hitler found himself in a situation similar to that which we encounter today while living in Vienna. Still a teenager or a young man, he was confronted with degeneracy on all sides. His friend August Kubizek reports how the young Hitler dealt with it:

In the midst of that corrupt city, my friend surrounded himself with a wall of unshakeable principles which enabled him to build up an inner freedom, in spite of the dangers around him. He was afraid of infection, as he often said. Now I understand that he meant, not only venereal infection, but a more general infection, namely, the danger of being caught up in the prevailing conditions and finally being dragged down into a vortex of corruption. It is not surprising that no one understood him, that they took him for an eccentric, and that those few who came in contact with him called him presumptuous and arrogant.

But he went his way, untouched by what went on around him…

Sound familiar?

Ultimately, a National Socialist must live a National Socialist lifestyle. To do otherwise would mean being false to whom he or she is. So even when it is difficult—indeed, even dangerous—he lives his outer life in accordance with his inner being. Yet whatever the cost, he has the great recompense of living his on his own terms. Even in the midst of racial decay and social decline, he lives in the New Order.

________________

About the author: Martin Kerr is the Chief of Staff of the NEW ORDER, the North American affiliate of the World Union of National Socialists.

Not so lonely!

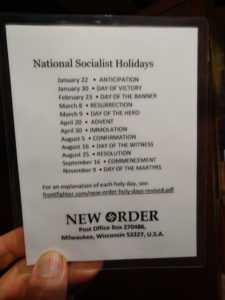

In ‘Under the Redwoods’ I described the loneliness of crossing what I call the psychological Rubicon: from Normieland to the lands of NS. But today I received some printed material from the mailman, including a paper leaflet ‘Introducing the New Order’.

Following my metaphor, I was very pleasantly surprised to discover that we are not so alone on the other side of the river. There are still people on this side after the fateful 1945!

One side of the leaflet I received today can be seen here. On my paper printout, I marked the first three paragraphs of this ‘Introducing the New Order’, and most of what we can read under the heading ‘A Community of Faith’. I also marked the words ‘We come together privately in formal ceremonies, services and celebrations,’ as they reflect exactly what I have been saying about how to found a new religion.

The text continues turning the page, which I could quote. But it is better for Aryans interested in becoming true National Socialists to get the leaflet.

Address given at the 2016

JdF 127 Hitler Festival

in Detroit, Michigan

by NEW ORDER Chief of Staff

Martin Kerr

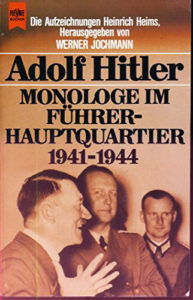

In the Table Talk, Adolf Hitler accepts as a matter of course that the figure commonly known as Jesus Christ was an actual historical person. He describes him as the leader of a popular revolt against the Jews of his time. Savitiri Devi, one of the best known and most eloquent of Hitler’s post-war disciples, felt otherwise. In her essay, Saul of Tarsus, she writes that based on her own extensive research, she believed that Jesus (whose name would have been Yeshua bin-Yusef al-Nazarini or something similar in his native Semitic tongue of Aramaic) was merely a fictional character from Christian mythology; that is, he was not an historical person.

It matters little to us today whether or not Yeshua was real, or whether he was as imaginary as Bilbo Baggins and Huckleberry Finn. But, of course, it does matter to the Christians, who have built up an elaborate if perverse theology based on his putative teachings. In fact, so important has he been to the Christian world that all historical dates are routinely calculated from the year that he was supposed to have been born. That practice started around the year 525 by a Christian monk named Dionysis Exiguus. Years after his birth were counted forwards and those before his birth were counted backwards. Traditionally, these designations have been known as AD for Anno Domini (or “Year of our Lord”) and BC or “Before Christ.” For reasons of Political Correctness, these old terms have now been replaced by CE (for “Common Era”) and BCE (“Before Common Era”).

But regardless of what initials are used, the basic method of calculating and enumerating the years of the calendar has remained unchanged, because Jesus—real or not—is held to be someone who “broke history in half.” In the Christian conception of things, there is an absolute rift between what came before him and what came after. In the conventional wisdom, Jesus changed everything.

______ 卐 ______

In the 1880s, a towering intellectual figure arose in Germany to challenge the accepted dispensation: the philosopher Friedrich Nietzsche. In his autobiography, Ecce Homo, Nietzsche suggested that it was he, Nietzsche, who was the one who would break history in half. Through a process which he called the “transvaluation of all values,” Nietzsche sought not just to supersede Christianity, but to reverse it. Thereby he would lay the foundations for a new European super-civilization. I imagine that in Nietzsche’s scheme of things, future historians would date all history from his, Nietzsche’s coming, and not from the advent of the one whom our Norse ancestors called the “Pale Christ.”

Nietzsche, we note, was completely ignored during his lifetime, except for some cursory interest that he aroused in philosophical circles, which had a negative, dismissive view of his work. That he grandiosely described himself as the man who would break history in half is widely viewed either as sarcasm on Nietzsche’s part, or else as a psychological defensive mechanism to protect his ego from the rejection he suffered from his colleagues.

Perhaps there is a modicum of truth to both of these explanations, but I feel at the heart of things, Nietzsche was being fiercely serious. He recognized the full import and significance of his teachings, even if his contemporaries did not. Today, we National Socialists recognize him as one of the earliest “fragments of the future,” someone who was not the “last of yesterday,” but rather was one of the “first of tomorrow.”

______ 卐 ______

As it turned out, neither the Christian savior nor Nietzsche was the one who broke history in half. The theology espoused by Jesus was merely a reshuffling of the older Semitic worldview, a prime feature of which was the belief that there is a dichotomy between spirit and matter. Spirit is pure and good, it tells us, while the flesh is impure and corrupt. Nietzsche, for all his genius, was unable to articulate a realistic, systematic alternative to the Christian worldview.

No, it remained to Adolf Hitler to be the man to shatter the dispensation that had held Aryan man in thrall for 2,000 years or more.

I do not know when the realization first entered the Führer’s mind that there is no division between soul and matter, but rather that our flesh is infused with and animated by our spirit, while spirit is given form by our bodies. It must have been at a very young age. Probably, it did not dawn on him all at once, but instead only emerged gradually as he matured intellectually. In any event, by the time that he sat down to write Mein Kampf, his basic worldview was already well-formed and complete.

Adolf Hitler believed that the universe was governed by natural laws, and that for man to be happy and successful, he must first acknowledge that these laws exist; secondly, he must discover what they are; and thirdly, he must live in accordance with them.

This is another way of saying that the universe runs according to the principles of Causality—that is, of cause-and-effect relationships—and that it does not operate on the basis of supernatural forces, or on the mental constructions and wishful thinking of intellectuals and ideologues, or on the religious fantasies of theologians.

But at the same time, he knew that the human soul or spirit was a reality. His consistent use of religious language and imagery, plus specific comments recorded in Table Talk, reveal the Führer to be a deeply religious man, even if his spiritual outlook was diametrically opposed to that of Christianity.

Rather than believing that Man is born as a sinful being who can only be rescued from eternal hellfire and damnation by accepting the good lord Jesus as his personal savior, Adolf Hitler believed that Man was born into a state of grace with the Natural Order. In the Hitlerian worldview, we are all holy beings at birth. It is through being raised with false beliefs, and thrown into a society out of synch with the Natural Order, that we lose our state of natural grace and holiness.

Matt Koehl once discussed the Christian conception of original sin with me, contrasting it to the Hitlerian outlook. “If you look at a newborn baby in its cradle, what do you see?” he asked. “The Christians see an evil being born in sin, and doomed to Hell and torment without the intervention of their savior. But as a National Socialist, I see an innocent and holy being, born into a state of harmony and grace with the Natural world.”

This is the Führer’s great gift to Aryan man—and, indeed, to the whole world: he has restored us to a state of grace with the Natural Order. Hitler made us holy again, and only the Gods have the power to sanctify.

______ 卐 ______

As Aryans, we may be endlessly, sincerely, and profoundly thankful on a personal level for such insights. But unlike the Christians, as National Socialists, we are committed not just to our own personal salvation, but to the salvation and resurrection of our Race.

How do we incorporate our fundamentally religious perception of National Socialism into the practical work of building Adolf Hitler’s earthly movement? We struggle with these issues today—but we are not the first to have raised such questions.

Our great forbearer, George Lincoln Rockwell, wrestled with this question as well. During the final year of his life he prepared to transform his tiny, noisy band of political dissidents into a mighty mass movement. In a passage from his book, White Power, he gives us his thoughts on the future religious or spiritual orientation of the movement:

National Socialism, as a PHILOSOPHY, embodies the eternal urge found in all living things—indeed in all creation—toward a higher level of existence—toward perfection—toward God.

This “aristocratic” idea of National Socialism—the idea of a constant striving in all Nature toward a higher and higher, more and more complex, and more and more perfect existence—is the metaphysical, supernatural aspect of our ideal.

In other words, concepts of social justice and natural order are the organs and nerves of National Socialism, but its PERSONALITY, its “religious” aspect—the thing that lifts it above any strictly political philosophy—is its worshipful attitude toward Nature and a religious love of the Great gifs of an Unknown Creator.

Christianity, for instance, is a far higher thing than its rituals, the words of its prayers, or any of its creeds. It is a SPIRITUAL STRIVING toward the believer’s ideals of spiritual perfection.

National Socialism is the same sort of striving toward even higher and higher levels here on this earth, while Christianity is striving toward a future and later life not of this earth.

For the ordinary “soldier” in our “army”, building and fighting for Natural Order—National Socialism—it is sufficient that they respect and obey the laws and doctrines established by the lofty ideals of our philosophy with merely an instinctive love of those ideals, perhaps not with the complete understanding of the highest forms of our philosophy.But just as the greatest Christian leaders have been those not preoccupied with details and rules but rather those who were “God intoxicated” with the highest ideals of the religion, the leaders among our National Socialist elite must share this fundamentally religious approach. For them the true meaning of our racial doctrine must be part of their idealistic “striving toward God.” [1]

Through total identification of ourselves with our great race, we partake of its past and future glories. When we contribute in any way, especially by self-sacrifice, toward helping our race along the path toward higher existence, we reach toward God—the Creator of the Master Race.

In short, while the mechanics and rules of National Socialism, as codified and set forth here, are sufficient for most of us, for the few idealists ready and willing to sacrifice their very lives in the cause of their people, National Socialism must be a very real religious ideal—a striving toward God.

We should all keep Commander Rockwell’s words in mind as we go forth into the world in the coming Jahre des Führers 127. We should endeavor to bring every single racially conscious White person into our Movement. But at the same time, we must maintain the ideological purity of our Cause by seeing to it that only those with a clear understanding of the spiritual, religious character of our worldview become Movement officers. And this is especially true with members of the senior leadership corps.

In this way, we will guarantee that we, too, are “breaking history in half,” in keeping with the Führer’s mission.

HEIL HITLER!

_____________

[1] From White Power, chapter XV, pp. 455-457.