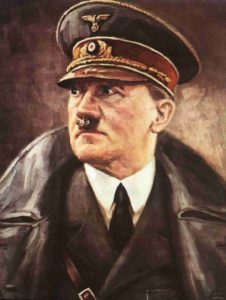

Hitler’s position at this time was complicated. He was still virtually unknown in most of Germany. The main Berlin newspapers ignored him and his party. They didn’t even report on the riotous Deutscher Tag at Coburg, whose resonance was confined to south Germany. Hitler had very few funders outside of Bavaria, with the notable exception of the Ruhr industrial baron Fritz Thyssen, who contributed substantially in the course of 1923. That said, within the non-particularist Bavarian right wing nationalist milieu, Hitler now enjoyed a commanding position. He was well known in Munich, which Thomas Mann described in a 1923 letter to the American journal The Dial as ‘the city of Hitler’. His speeches drew large and ecstatic crowds. Karl Alexander von Müller, who heard him speak for the first time at the Löwenbräukeller in late January 1923, describes the ‘burning core of hypnotic mass excitement’ created by the flags, the relentless marching music and the short warm-up speeches by lesser party figures before the man himself appeared amid a flurry of salutes. Hitler would then be interrupted at almost every sentence by tempestuous applause, before departing for his next engagement.

Over the next few months, the tempo of Nazi events and activities increased. There were in excess of 20,000 NSDAP members at the start of 1923, and that figure more than doubled over the next ten months to 55,000; the SA nearly quadrupled from around 1,000 men to almost 4,000 during the same period. Hitler himself was so prominent that the NSDAP was widely known as the ‘Hitler-Movement’, the term under which his activities were now recorded by the Bavarian police. He had become a cult figure. The Völkischer Beobachter became a daily paper in February 1923, giving preferential treatment to the printing of Hitler’s speeches. Two months later, it began marking the Führer’s birthday, an honour not accorded any other Nazi leader. He had long given up the humble role of drummer. Hitler spoke once again of the need for a dictator. The German people, he claimed, ‘are waiting today for the man who calls out to them: Germany, rise up [and] march’. There was no doubt from the context and rhetoric that he planned to play that role himself. His followers styled him not merely the leader of the national movement but Germany’s saviour and future leader. The Oberführer of the SA, Hermann Goring, acclaimed him at his birthday rally on 20 April 1923 as the ‘beloved Fuhrer of the German freedom movement’. Alfred Rosenberg described him simply as ‘Germany’s leader [Führer]’.

Conscious of his tenuous position within the Catholic Bavarian mainstream, Hitler continued to try to build bridges to the Church, or at least to its adherents. ‘We want,’ Hitler pledged, ‘to see a state based on true Christianity. To be a Christian does not mean a cowardly turning of the cheek, but to be a struggler for justice and a fighter against all forms of injustice.’ The NSDAP did succeed in making some inroads among Catholic students at the university and the peasantry and in winning over quite a few clerics, including for a while Cardinal Faulhaber, but for the most part Hitler made little headway.

There are two things we might comment on in this passage.

First, we are living in a world of soft totalitarianism. We can already imagine a National Socialist party in Europe today that could recruit thousands of members! That would not even be possible in the US, despite its hypocrisy in claiming that its amendments allow citizens both free speech and freedom of association (in reality, Uncle Sam allows neither, as we saw a few years ago in Charlottesville).

The other issue is this saying that true Christianity doesn’t turn the other cheek but fights injustice. While a hundred years ago it was possible to use this kind of rhetoric in the more conservative sectors of Bavarian society, today it is impossible. The mainstream Christian churches follow the zeitgeist of our century, without exception. I am not criticising Hitler’s use of this rhetoric. But under the circumstances, post-1945 National Socialism must reinvent itself.