Rose Mularczyk reported on a massacre in Gross-Kikinda in North Banat which was perpetrated on 3 November 1944 under the leadership of ‘Commandant’ Dusan 0PAÈAE in a dairy warehouse:

Rose Mularczyk reported on a massacre in Gross-Kikinda in North Banat which was perpetrated on 3 November 1944 under the leadership of ‘Commandant’ Dusan 0PAÈAE in a dairy warehouse:

First the men were stripped naked and forced to lie down on the floor. Then their hands were tied behind their backs. Then they were horribly beaten with bullwhips. After this torture their tormentors began cutting strips of living flesh from their backs. Others had their noses, tongues, ears and genitals cut off. Then their eyes were gouged out, and in the meantime the floggings continued.[1]

Such beastly mutilations were by no means exceptional. In Kubin, Germans were hacked and sawed to pieces, then burned alive. An eye witness reported that Hilde Kucht, the leader of a women’s association, ‘had her breasts cut open and pieces of flesh cut out of the lower abdomen while alive, and that several other persons were tied together in a group, smeared with tar, set afire and the corpses were burnt to a cinder’.[2] This for the time being is more or less the foretaste of ‘liberation’ of the ethnic Germans (Volksdeutsche).

In fact, during the war all the Allies committed crimes that have never been acknowledged as such, let alone atoned for. On this matter there is enough documented evidence to fill many libraries. We must limit ourselves to just a few examples, primarily atrocities perpetrated on the civilian population.

On 13 February 1945, there were crowding into Dresden, one of the most beautiful and culturally significant cities of Germany and all Europe a half million refugees, besides the normal population of around 600,000. The metropolis, which until this time had been spared bombardment and was declared a hospital-town, had practically no air defence or night fighter planes. At 22:00 hours the first ‘Thunderclap’ occurred, as the Anglo-American bomber units were to call their terror bombing. To begin with, the British bombers of the Royal Air Force opened the attack by dropping high explosive bombs on the inner city. This was followed immediately by 570,000 incendiary stick bombs and 4,500 flame-jet bombs. This bombardment of firebombs created a devastating firestorm, tolling the death-knell for this hospital city dedicated to the arts. Up to this time, there had been relatively little loss of life. Most of the people had managed to find safety in their cellars. When the first attack was over, they came out to discover huge fires in the city. Yet, the British bombers returned—no early warning. Only two-and-a half hours later, at approximately 1.30 hours of the morning of February 14, the second bombing wave arrived. To begin with, 4,500 high explosive or demolition bombs were exploding in rapid secession, causing countless houses to collapse. Thousands of people were trapped and buried alive under steel and concrete.

(The ruins of Dresden, photograph taken in April 1946. While the first wave of attack had transformed the old city into an ocean of flame, the second wave was trying to prevent the fire-fighting operations with demolition bombs, so that of the 1.3 million human beings in the city as many as possible would burn to death.)

(The ruins of Dresden, photograph taken in April 1946. While the first wave of attack had transformed the old city into an ocean of flame, the second wave was trying to prevent the fire-fighting operations with demolition bombs, so that of the 1.3 million human beings in the city as many as possible would burn to death.)

Already at that time, the British were guilty of a war crime: They had systematically bombed a city-centre with its civilian population and not, for example, military-strategic objectives or industrial centres. The most important military target was approximately one and a half kilometres away from the wrecked city centre: the main railway station. Tens of thousands of refugees and people bombed out of their homes were congregating here. The railway lines, mostly undamaged, were jammed with hundreds of railway carriages, so that an immense mass of people was now packed in a closely confined area. It was onto these people that the British let rain down primarily firebombs and liquid incendiaries. The station platforms and the immediate vicinity of the station were strewn with dead people, with people dying, with people burning and with human body parts. Tens of thousands who had survived the inferno now sought refuge on the meadows along the Elbe and in the Great Garden (Grossen Garten), where they thought they would be safe after the terrors of the night. But it was now the turn of the Americans, specifically the US Eighth Air Fleet, to finish off these helpless women and children, these defenceless men and old people. Just after fifteen minutes past noon, some 760 bombers dropped, amongst other things, 50,000 incendiary stick bombs on the refugees. After that some 200 fighter-bombers went over to a low-flying ‘hedge hopper’ attack and opened fire with their machine guns on the civilian population.

The Anglo-American bomber units had committed mass murder—yet, they have never been called to account for this. But not only that:

As well as the people, Dresden’s most beautiful and world-famous buildings, parks and gardens were destroyed. These included the Zwinger, Hofkirche, Schloss, Oper, Grünes Gewölbe, Bellevue, italienisches Dörfchen, Landtagsgebäude, Palais Cosel and many others. The Japanische Palais, the largest and most valuable library in all Saxony, was completely gutted. Blockbuster bombs smashed the Brühlsche Terrasse. The Belvedere lay there with gaping holes for windows. The dome of the Frauenkirche collapsed and the tower of the Schloss, as well as the spire of the Sophienkirche, were burnt out. Of the upper part of the Rathausturm (City Hall Tower) there remained just the skeleton.[3]

The three-stage terror thrust against Dresden—there is no other term possible for these bombings—was not at all undertaken because of a military necessity. There was neither industry worth mentioning nor munitions nor military stores in the inner city, the centre of the attack. The fact that the infrastructure was only relatively slightly damaged—of the transportation system only the main railway station was destroyed, while the bridges over the river Elbe remained intact—shows all too clearly that the Anglo-American attack on Dresden was just as senseless, The war was not shortened thereby, as it was a completely unjustifiable act of destruction and genocide.

According to the police report, altogether there had been recovered, up to the 22 March 1945, more than 200,000 dead. This was not to be regarded as the final count, however, because of ongoing rescue work. Later calculations or counts infer a total of up to 400,000 dead. Of the dead bodies recovered, only 35,000 could be identified. From official data, there is merely this relatively small number of dead given as the total of victims to be mourned. It reflects the questionable understanding of the scholarly approach and the attitude towards authentic historiography in the Federal Republic. Seen from the platform of criminal law, it seems not to fall under the more than doubtful interpretation of the law in the sense that here evidently the facts of the case are not ‘disparaging the memory of the dead’.

(Particularly malicious acts: After the bombing attacks, often low flying aircraft would turn their attention onto the survivors. Yet, the Allied terror bombings directed against the German civilian population achieved the very opposite of their intended purpose. The morale of the German people was not shattered by this.)

(Particularly malicious acts: After the bombing attacks, often low flying aircraft would turn their attention onto the survivors. Yet, the Allied terror bombings directed against the German civilian population achieved the very opposite of their intended purpose. The morale of the German people was not shattered by this.)

This type of ethnic cleansing is by no means an exception; rather, it is just a question of transforming into action a precisely worked-out plan for the surface area bombing of German towns, as done by Frederick A. Lindemann, Churchill’s adviser for aerial warfare.[4] The Allies were proceeding according to ‘Plan F’, as it were, as is demonstrated also in the representative example of the destruction of Stettin in August 1944: ‘Plan F’ was built around the deliberate targeting of residential areas and historical buildings, after the contemptuous-of-mankind-method ‘we don’t give a damn’. Firstly, they would drop aerial mines and high explosive bombs, followed by canisters of phosphorous. This tactic never fails its hundred per cent deadly effect. In the attempt to save themselves from death by suffocation, the defenceless victims clamber out of their ruined cellars, but once in the open, they are caught by the firestorm and become human torches, writhing and screaming in agony until death finally releases them.[5]

(German civilian victims of Allied bombing raids; weight of bombs dropped: 2,767,000 metric tons!)

(German civilian victims of Allied bombing raids; weight of bombs dropped: 2,767,000 metric tons!)

In this connection there must also be cited the bombings that were contravening the international laws of warfare as, for example, of these cities Cologne, Ulm, Magdeburg, Aachen, Graz, Kiel, Dortmund, Hamburg, Nuremberg, Klagenfurt, Würzburg, Kassel and Potsdam. There are many more, but particularly smaller towns as, for example, Hanau, Pforzheim, Bingen, Darmstadt, Heilbronn, Villach, Nordhausen, Hildesheim, Freiburg i. Br., Halberstadt, Emden, Frankfurt/Oder that could be listed: towns and cities which had no military usefulness or advantage. These attacks served the exclusive purpose of destroying human life.

The Austrian Maximilian Czesany, historian and expert on aerial warfare, has generously compiled a concise account concerning these terror raids—of the grossest violations of international law as perpetrated by the Anglo-Americans: ‘The way they were conducting their aerial warfare, the USA and Great Britain were violating the rules and standards of the Laws and Customs of War, which they had ratified only decades before, as is shown by the following:

• the general provisions of Laws and Customs of War according to which military clashes must only be directed against combatants, quasi combatants and military objectives, and all means of combat causing unnecessary suffering or damage are forbidden;

• Article 27 of the Hague Convention IV Respecting the Laws and Customs of War on Land states that: ‘In sieges and bombardments all necessary steps must be taken to spare, as far as possible, buildings dedicated to religion, art, science, or charitable purposes, historic monuments, hospitals, and places where the sick and wounded are collected, provided they are not being used at the time for military purposes’; Article 46 of the Hague Convention states that ‘the lives of persons, and private property, as well as religious convictions and practice, must be respected’;

• the Geneva Protocol of 1925, which forbids ‘the use in war of asphyxiating, poisonous or other gases, and of all analogous liquids, materials or devices’.[6]

With the Allies’ unrestrained aerial warfare against defenceless civilians, the Anglo-Americans in particular made themselves guilty of genocide, of a war of extermination.

(Nuremberg in 1945. Like most German cities, it is a mass of ruins and debris. Germany was covered in 400 million cubic metres of rubble.)

(Nuremberg in 1945. Like most German cities, it is a mass of ruins and debris. Germany was covered in 400 million cubic metres of rubble.)

The Soviets also bear a large part of the guilt for the annihilation of the German people. The deliberate attacks on the refugee columns are to be especially condemned. Soviet submarines and pilots are deserving of the inglorious distinction of having simply shot down tens of thousands of refugees fleeing by land and water. The people that were fleeing became the massive victims of Soviet low-flying attacks, of Soviet tank units and infantry units following; their occupation troops dealt with those who had found temporary refuge within communities. Enemy units were attacking columns of refugees ever more frequently. This occurred, for example, on 12 February 1945, when refugees from the area of Hanswalde in the Heiligenbeil district were crossing the Frische Haff in the direction of Danzig-Gotenhafen. ‘Suddenly Soviet aircraft began bombarding the refugee column. Low-flying aeroplanes dropped bombs on the helpless refugees while strafing them with their armaments. The ice was coloured red with blood after the attacks. People and horses, ripped to shreds, were lying about in the snow, the carts smashed. A scene of horror’.[7]

Naval chaplain Arnold Schumacher describes how in March of 1945 the Soviets bombed to pieces Gotenhafen and Hela, when these places were bursting at the seams with refugees and retreating soldiers. The ferry from Gotenhafen to Oxhöft, where the refugee boats headed to sea, remained in service throughout the evacuation. During the crossing on 25 March, the passengers experienced ‘a terrifying low-flying attack that was repeated again and again. The enemy airmen were amusing themselves by hunting down and killing the people, who were ducking in the grass or clawing into the ground. Oxhöft was filled with thousands of sailors. The Russians had reached the Oxhöfter campaigners and were mercilessly firing their shells and mortar into the solid mass of people, barely able to defend themselves anymore’.

After these attacks, the German Navy accomplished the outstanding achievement of taking to Hela tens of thousands of refugees, without any losses. But here also the Soviet Air Force was flying one concentrated attack after the other, dropping their bombs into the tightly packed mass of people. ‘For me, the bitterest experience of the whole war was that in the final months countless people were killed who were unregistered, and whose deaths, unrecorded. Everywhere in Germany people were waiting with hope in their hearts that their loved ones would someday reappear, but in reality they had been lost at sea or buried in unmarked graves’.[8]

In February 1945, the General Steuben was sunk with the loss of at least 3,000 refugees. On 3 May, in the vicinity of Neustadt (Lubeck Bay), both the Thielbeck and the passenger ship Cap Arcona were destroyed by British Typhoon fighter bombers after several waves of attack—the shipwrecked survivors were fired upon with the aircraft armaments. Both ships had been brought into action for the biggest evacuation in history. Onboard were mostly prisoners from the concentration camp Neuengamme, and amongst them were several former members of the Reichstag who belonged to the SPD as well as the German Communist Party. Between 2,000 and 5,000 persons were drowned in the sea. On 16 April, the overloaded 5,300 register ton freighter Goya was sunk, dragging almost 7,000 wounded soldiers and refugees down to their death. Only 195 people survived.

(On 5 May 1945, ships were still placed in Hela harbour to rescue over 40,000 people from the Soviet Russians. Here, civilians are waiting at the fishing port.)

(On 5 May 1945, ships were still placed in Hela harbour to rescue over 40,000 people from the Soviet Russians. Here, civilians are waiting at the fishing port.)

Karl Beckmann, the on-duty loading officer on board, was on patrol duty when the ship received two hits at 23:56 hours. The ship began to sink rapidly and, after the boilers had exploded, went down into the depth. All this took no more than three to four minutes. Beckmann recalls: ‘According to my estimation, there were several hundred people in the water. Judging by the voices, many were women and children. A chorus of voices was shouting for help; all around me were people cursing, crying and gurgling, as they were sinking. Somewhere, in the expanse of water, someone shot himself while others, who had already drowned, were floating among all the ship’s debris… The chorus of voices was growing fainter, and the cries of the drowning people—the cold and the excitement draining them of the last bit of strength—were weighing terribly heavy upon my train of thought remembering former, happier times, sudden realizations of the many mistakes I had made, and a resolution to change my attitude to life should I somehow survive’.[9]

On 30 January 1945, the hopelessly overfilled 25,000-ton Wilhelm Gustloff was sunk near Stolpmünde by the Soviet submarine S-13. The Wilhelm Gustloff was a former KdF-ship: Kraft Durch Freude, ‘Strength Through Joy’, a popular government programme that built several large cruise ships for German workers during the National Socialist economic miracle of the 1930s. Pressed into service as a refugee transport, the Gustloff was struck with three torpedoes. According to the Deutsche Militärzeitschrift (German Military Magazine), they were drowned in icy waters—the temperature of the water being 2 Celsius, with an air temperature of minus 18C—out of a total of 10,582 people (made up of refugees, severely wounded soldiers, women’s naval auxiliaries and crew members) 9,343 human beings.[10]

(One of the last transports from the island of Hela across the Baltic Sea. By taking the sea route, more than two million people could be saved from the clutches of the Soviets.)

(One of the last transports from the island of Hela across the Baltic Sea. By taking the sea route, more than two million people could be saved from the clutches of the Soviets.)

The tragedy of her going down is recalled in the accounts of the few survivors. One of these recalled: ‘Suddenly everything went quiet as the ship went down, taking us with it. I forced my eyes open and saw how my son, then my daughter and then my husband were forced out through the open window. I wanted to scream “Take me with you”, but could not, because water had already filled my mouth. Then I realized that I too was being forced through the window. It was horrible—nothing but water, water everywhere, and no more air in my lungs. I wanted to scream but could not. Slowly I rose higher and higher, until I reached the surface, where I was able to cling to a rescue boat. I was fully conscious all the time. After a long time, when I was no longer able to hold on, I was pulled into the boat. Once inside, I lost consciousness and my body was benumbed with cold. When I came to again, I found myself onboard a Navy ship, where they let me thaw out under a hot shower. After the third attempt of resuscitation, I finally regained consciousness and realized that it had not been a dream, but harsh reality. I had lost my husband and the children’.[11]

For those who had survived the sinking of the ship, that night of terror would remain the worst experience of their lives. A retired district official, Paul M., even goes so far as to state: ‘After that, everything I had to endure in the prisons and concentration camps of the victors was child’s play compared to the going down of the Gustloff. In the most terrible situations the one thought that kept me going was that things were a lot worse on the Wilhelm Gustloff’.[12]

The sinking of the refugee ship Wilhelm Gustloff was the greatest maritime disaster in history. A comparison: In recent times there was a sensation-seeking media marketing of the sinking of the Titanic in 1912, where the number of people that went to their death was 1,513.

Scenes from Franz Wisbar’s 1959 film Nacht fiel über Gotenhafen (Night came down on Gotenhafen) that documented the Gustloff catastrophe from Baltic archives of H. Schön.

As the Red Army ‘liberators’ advanced further into Eastern Germany, the Poles grew more daring with every kilometre. Now it was not just all Germans and ‘collaborators’ who were subjected to atrocities and maltreatment, but also Allied prisoners of war or, rather, foreign workers, especially French, English, Dutch, Flemish people and Walloons. These Western Europeans, but also Ukrainians and members of the Baltic nations, kept almost exclusively close to the side of the fleeing German population. With no consideration for their nationality, these too were robbed, beaten, raped and murdered. In remembrance of these European people let it be emphasized and recorded that these treks fleeing to the West were often accompanied by French prisoners of war and also Belgian, Dutch and French civilian internees, who had been sent to work on the farms in Eastern Germany. They frequently put themselves in front of the German women, children and old people during dive-bombing attacks, and when these were being molested, even giving their lives for these defenceless people. Lieselotte W., who was 16 at the time, reports that when the Soviets arrived in Samland: ‘The Russians came at night, looking for young women and girls and raping them. When the French prisoners of war realized what was going on, they came to our assistance and protected us from the Russians’.[13]

Let us look at a few examples that should verify how strong the solidarity of these people, basically prisoners of war, with the Germans really was. From this fact we can undoubtedly conclude that, in the first place, foreign workers and prisoners of war in National Socialist Germany were treated correctly. Otherwise, they would have gone over to their ‘liberators’ with all flags flying. In the second place, for most of what later was to be blamed on the Germans—murdered prisoners of war and foreign workers— was to be charged to the Communist or, rather, chauvinistic ‘liberators’ from the Soviet Union, Poland and from Czechoslovakia. For example, the village of Weizdorf in the Rastenburg district of East Prussia was taken by Soviet troops on 27 January 1945. During the plundering rampage through the village, the French located there were not spared either. Billeted at an estate, ‘twelve French prisoners had their fingers hacked off to get at the rings. Then they were shot in the neck by the dung-heap outside the horse stable. We were all made to stand there to watch. Then the following persons had the sinews cut in both of their hands with bayonets and razor blades’.[14]

The killing of non-Germans by the Red Army was not an altogether rare occurrence. In the East Prussian village of Nemmersdorf not only did almost all of the German population fall victim to the murderous Soviet frenzy, but also fifty French prisoners of war. They were all shot by the Soviets. And Friederike Scharwies, a farmer’s wife from Labau, also has very positive memories of the French prisoners without exceptions. They were ‘full of human pity and compassion for the terrible plight and misery of the Germans’. Frau Scharwies describes an instance of the chivalrous conduct of the French workers toward German girls, who had been physically and sexually maltreated: ¡’A young woman, about 35 years old, was led in, her eyes cast down very low. After a long time, she finally raises her head and looks about helplessly, like a crippled deer. Suddenly she calls out a name; straight away a French man jumps up and catches her in his arms, as she weakly sinks to the ground. I myself am also at pains, so to speak, to comfort the martyred girl. Other French men get off their bench and she is laid down’.[15]

When Danzig fell to the Soviets, a great many foreign nationals, especially Dutch, were kept in concentration camps along with the Germans, where they too were completely at the mercy of the invaders.[16] Many of the Western European prisoners of war and foreign workers, while trying to escape their Soviet ‘liberators’, were robbed, tortured and murdered, just like the Germans. They too were stripped of their boots and warm clothing, and even had their gold teeth brutally knocked out.[17] There are many documented incidents of French men being slaughtered alongside the Germans. In one barn in the Labiau district, around thirty French workers were shot when they refused to hand over their last possessions to the Soviets.[18]

In completion of this part, it must also be stated that, in general, most of the American soldiers in the Sudetenland were behaving humanely concerning the German people, often protecting them from the violations of the Czechs. How they differed from their comrades in West and Central Germany! There are tens of thousands of documented cases of atrocities and violations of international law committed by the democratic Allies against German soldiers and civilians. Among other things field dressing stations, ambulances and hospitals, all with clear recognizable identification markings, were shot at and bombed by the Americans. During ground attacks, the Americans were forcing human shields of German civilians and prisoners of war to be put in front of their troops, even tying the German men to their tanks. German soldiers who had already surrendered or were wounded, were systematically murdered. This would also apply to the transports of prisoners of war as, for example, those sent to Canada or the US.[19]

During the ‘liberation’ by the Western Allies there were mass rapes of German women and girls, often by American Negroes and French colonial troops. Plundering was the order of the day. Women and old men working in the fields, as well as children playing in the street, were routinely targeted by American, English, Canadian and French aircraft. Especially in France, street mobs stoned, clubbed and stabbed German prisoners of war and robbed them of everything they owned. During so-called interrogations, German prisoners of war were regularly subjected to torture and other crimes forbidden by international law. The Americans, British and French were equals in every way in this respect.

(Before capitulation of the Wehrmacht, the invasion of defeated Germany by the Western Allies was distinguished from that of the Red Army only by the extent of the perpetrated crimes.)

(Before capitulation of the Wehrmacht, the invasion of defeated Germany by the Western Allies was distinguished from that of the Red Army only by the extent of the perpetrated crimes.)

In this regard, the orders of the 4th English Tank Brigade in North Africa for handling prisoners of war are very informative: ‘The interrogation of prisoners of war is an extremely valuable source of information, especially when the questioning occurs while the prisoner is still shaken, and not yet in full possession of his mental faculties. The prisoners of war must not be allowed food, drink, sleep or any comfort or favour. Further, any conversation with the relevant section before the actual interrogation is strictly forbidden. Any action of comradeship, such as offering a cigarette, would create an impression of weakness in the Germans, and would destroy the prospect for a successful interrogation’.[20]

Thus, in testimonies of former German prisoners of war, one repeatedly comes across reports such as: ‘They put us in cattle trucks. Then civilians began to climb up on the outside and spat into the trucks. This also happened in the truck where I was. During the whole trip we were given hardly anything to drink, just one pitcher of wine on one occasion, and very little to eat. We were not given any opportunity to go to the lavatory. With beakers we would catch rainwater from the roof gutter and satisfy our thirst that way’ (France).

‘Whenever we tried to open the hatches at any stop, the guards would poke their bayonets inside. When asking to go to the lavatory, Lt. Sommer would yell: ‘Don’t eat anything and you won’t need to shit, don’t drink anything and you won’t need to piss’ (France).

‘We sucked hard at cracks in the walls to get air, and no one spoke a word, just to have the barest minimum of air supply come in. I myself and three comrades came near dying for lack of air. The hatches were closed every evening around five o’clock and not opened again until nine o’clock next morning’ (North Africa).

‘I refused to give any information and Lt. Ludwig struck me in the face with his whip, which knocked out one of my teeth and left my lip bleeding’ (France).

‘Because the work quota could not be attained, several randomly selected individuals were brought out. These were made to strip naked and then: flogged by French non-commissioned officers (NCOs) with riding whips, put on half rations and thrown in the so-called dog kennel. This was a barbed-wire enclosure or pen, of one and a half metre long and about two metres wide and covered over with barbed wire’ (North Africa).

‘The Gaullist commandant of Oudna camp, southwest of Tunis, allowed the German prisoners of war only insufficient nourishment for their exhausting labour. The supplementary rations, promised for hard labour, were not issued. In addition to malaria, typhus and dysentery, severe malnutrition soon became evident. When, as a result of such abuse, the German prisoners of war would attempt to escape, after recapture, they would be placed in the so-called bunker. This meant that the prisoner was forced to dig a hole that was just long enough for him to lie down in it. He was forced to remain in the hole eight to fourteen days under close guard, on bread and water, most often without protection against the cold of the night’ (North Africa).

‘In the British transit camp of Bone, the German medical orderlies were forced, for the most part, to sleep in the open at night, as there were not enough English tents available. The food ratio was inadequate and the water ratio was catastrophic. Once every three days they received just one and a half litres of water, although the daytime temperatures reached sixty degrees centigrade’ (North Africa).

‘The detention cells were heavily barred and extremely dirty. There was only one latrine, which was also used by the Canadian guards. These people obviously were not familiar with the use of latrines, since they constantly covered the seats with excrement’ (Canada).

‘The heat was stifling in the tents. In the larger tents, thirty to forty severely wounded men had to lie close together, while the temperature inside was fifty-five to sixty degrees centigrade. The lightly wounded were packed in up to sixty men per tent. Given such cramped spaces and such temperatures, there was a constant stench of festering matter and also the plague of vermin’ (North Africa).

‘As a form of punishment, the whole camp had to be cleared one day, and around a hundred American military police were called in. The Germans were driven out of the main cage into the anteroom and the tents searched. All the wood was smashed and personal objects such as photographs and keepsakes were smashed and trampled on. The Americans were wreaking the most dreadful havoc’ (France).

‘This American clubbed the surviving Germans to death with the rifle butt’ (Italy).

(In France, after the capitulation of Paris, many German soldiers were severely mistreated by French Partisans.)

(In France, after the capitulation of Paris, many German soldiers were severely mistreated by French Partisans.)

It has been proven beyond doubt that officers and guard personnel of the democratic states most brutally violated the Hague Regulations on Land Warfare as well as the Geneva Convention, which had been established and formulated for the protection of the sick and the wounded, of prisoners and the civilian population, and to which these states had put their signature. It happened very frequently that German soldiers, who had surrendered and had laid down their arms, were murdered by the ‘liberators’. For instance, in the Lower Silesian town of Neuhammer, when German anti-aircraft units, along with other artillery and armoured tank units that had already surrendered to the Soviets, they were shot to the last man while the residents were forced to watch the shootings.[21] In Czechoslovakia it happened frequently that German soldiers, who had surrendered, were nailed to trees and then used as targets by the Czech partisans. Eye witness Walter Pachmann reports that several months after the ceasefire, German soldiers and airmen were still being murdered in beastly fashion near Prague. They were made to dig their graves and mix reinforced concrete. ‘Then they had to climb down into the graves, and we had to fill them with concrete up to the soldier’s knees. Then we had to get iron bars and stick them around the soldiers in the fresh concrete. Then we filled the hole with concrete up to the soldiers’ chest. After the soldiers had stood like that for a day, they would be blown up, before our eyes’.[22]

(One of the first photographs documenting Soviet war crimes. On 21 August 1941, the Red Army in Kingisepp [Luga] murdered and then mutilated the German soldiers that had been taken prisoner. The soldier, who had taken the photograph, saved it through war and imprisonment!)

(One of the first photographs documenting Soviet war crimes. On 21 August 1941, the Red Army in Kingisepp [Luga] murdered and then mutilated the German soldiers that had been taken prisoner. The soldier, who had taken the photograph, saved it through war and imprisonment!)

Oberleutnant Paul Böttcher, a holder of the Knight’s Cross (Ritterkreuzträger), describes the illegal, under international law, the conduct of the Soviets in sick-bays in East Prussia and gives us, as an example, the military hospital in Heilsberg: ‘When the Russians arrived at the military hospital on 30 January 1945, they behaved like wild beasts. They went from bed to bed with pistols drawn, looking for officers, Vlassov soldiers and members of the SS. They shot these Russians in their beds and took everything from the wounded. Nurses and other young women, who were seeking refuge in the military hospital, were thrown onto the tables, had their clothes ripped off and were raped by the Soviets in front of the wounded soldiers. Each one of these poor girls had to suffer ten to twenty Russians. The girls were screaming horribly. After the criminal and inhuman action, the Russians would kick each girl in the stomach’.[23]

Hauptmann Hermann Sommer, on the staff of the fortress commander and Wehrmacht headquarters in Konigsberg, reported that the identification of the corpses was very difficult, ‘because the Russians had poured petrol over the piles of bodies in an attempt to burn them. However, several hundred corpses could still be photographed, and these photos are recording facts of the matter, recalling the most gruesomely violent way to die. These pictures and the reports from the criminal investigation officers emphasize the point that most of the bodies showed injuries caused by cuts and heavy blows. Only a few had simple gunshots to the back of the neck. On a considerable number of women, the breasts had been torn off, the genitals lacerated with knives and abdomens slit open’.[24]

(Historians such as Franz W. Seidler carried out excellent educational work on war atrocities committed by the Red Army in Verbrechen an der Wehrmacht und Kriegsgreuel der Roten Armee [Crimes Committed Against the Wehrmacht and Other Atrocities of the Red Army], documenting 500 cases with written descriptions and photographs. Right, when the Soviets recaptured the city of Feodosia in Crimea on 29 December 1941, some 160 wounded German soldiers lying in the field were murdered with bestial brutality. This is one of the victims.)

(Historians such as Franz W. Seidler carried out excellent educational work on war atrocities committed by the Red Army in Verbrechen an der Wehrmacht und Kriegsgreuel der Roten Armee [Crimes Committed Against the Wehrmacht and Other Atrocities of the Red Army], documenting 500 cases with written descriptions and photographs. Right, when the Soviets recaptured the city of Feodosia in Crimea on 29 December 1941, some 160 wounded German soldiers lying in the field were murdered with bestial brutality. This is one of the victims.)

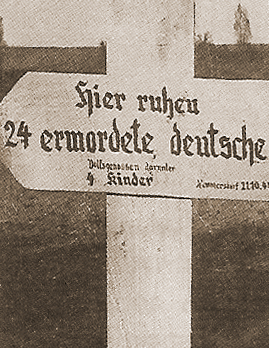

It soon became evident, once the German Wehrmacht had retaken villages in Eastern Germany, what was to await the German population when taken ‘under the wings’ of the Soviets. For example, the East Prussian village of Nemmersdorf was once more liberated (truly) after 24 hours. This short period was time enough for the Red Army to carry out a horrific bloodbath among the civilian population. A member of the Volkssturm (home guard) reported that many women were stripped naked, in crucified posture were nailed through their hands on barn doors and then brutishly raped. Little children and the elderly had their skulls smashed in, and the inhabitants of the village in general were horribly mutilated and disfigured. ‘On the sofa in one room, still in sitting position, we found an eighty-four years old woman who was blind and was already dead. This dead person had half a head missing, apparently hacked away from the neck, from the top down, with an axe or a spade’.[25]

(One of many documented cases of cannibalism: German prisoners of war, having died a gruesome death, are mutilated and disembowelled.)

(One of many documented cases of cannibalism: German prisoners of war, having died a gruesome death, are mutilated and disembowelled.)

These accounts are not all about National Socialist propaganda. These aforementioned violations of international law (Law of Nations) have been, as similarly done at the time for the investigation of the Soviet crimes in Katyn, investigated and documented by an international commission and a delegation of neutral journalists from Switzerland, Sweden, Spain and France. The circumstances in the East Prussian garden town of Metgethen were very similar. On 19 February 1945, combined Wehrmacht and Hitler Youth forces freed the town from the Soviet Rifle Regiment 950, under the command of Oberstleutnant (Lieutenant Colonel) Subzenko, and from the 262 Rifle Division commanded by Generalmajor (Major General) Usachev. There were horrendous sights here too, bearing witness to the incomprehensibly brutal conduct of the Red Army: ‘ln almost every room lay a woman half-naked, or completely naked, in the same position in which she had been raped.

(The East Prussian village of Nemmersdorf in the Gumbinnen district was one of the first German villages conquered by the Red Army, 20 October 1944. Soon afterwards, it was retaken by German troops, and indescribable atrocities of the Soviets came to light. Just as in Nemmersdorf, so did the de-humanized Soviet bands of soldiers wreak their frenzied havoc in other places such as Metgethen near Königsberg.)

(The East Prussian village of Nemmersdorf in the Gumbinnen district was one of the first German villages conquered by the Red Army, 20 October 1944. Soon afterwards, it was retaken by German troops, and indescribable atrocities of the Soviets came to light. Just as in Nemmersdorf, so did the de-humanized Soviet bands of soldiers wreak their frenzied havoc in other places such as Metgethen near Königsberg.)

Beside most mothers lay two or three children, likewise murdered in bestial fashion. Many of the dead children were still the age of nursing infants. Many of the women and girls lay in pools of congealed blood, which had run out of their genitals. According to the diagnoses made of the 8- to 12-year-old girls, the genitals had been ripped open, and then they were raped. On all the dead bodies were found many cuts made by bayonets and many rifle bullets’.[26]

Given the bestial cruelty of the ‘liberators from the East’ it seems reasonable to suspect that political calculation was behind the atrocities perpetrated on the Germans. Such was indeed the case. Wilfried Ahrens, a publicist dealing with the crimes associated with the expulsions, rightly came to the conclusion that the deliberate acts of brutality committed on the German civilian population were the opening act of a deliberate policy—calculated from the outset—of driving the Germans out from the land.[27] The Germans living in the areas that were to be annexed had to be driven into a panic-stricken stampede and, what is more, this was done with the callous calculation. Those who fled no longer need to be driven out; the territory is thus deserted and, therefore, is now freely available.

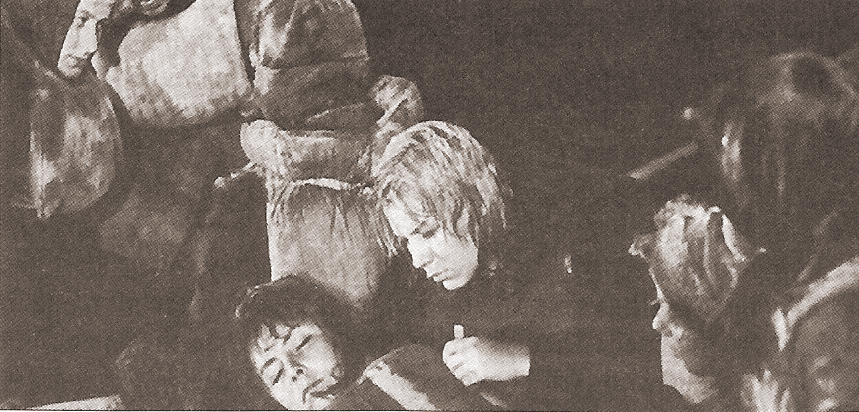

One of the young victims of Metgethen, typical of thousands,

and representative of the bestial behaviour of the Soviets.

______________

[1] Arbeitskreis Dokumentation (Ed.), Verbrechen an den Deutschen in Jugoslawien 1944-1948. Die Stationen eines Völkermords (English edition: Genocide of the Ethnic Germans in Yugoslavia 1944-1948, Documentation Project Committee, München 2006, p. 60), 2nd edition, Munich, Donauschwäbische Kulturstiftung, 1998, p. 103.

[2] Ibid., p. 105 (Engl. ed. p. 57).

[3] Maximilian Czesany, ‘Die Feuerstürme von Dresden und Tokio’ (The Firestorms of Dresden and Tokyo), in Deutsche Monatshefte, Vol. 2/ 1985, p. 38.

[4] Erich Kern, Von Versailles nach Nürnberg. Der Opfergang des deutschen Volkes (From Versailles to Nuremberg. The Martyrdom of the German Nation), 3rd edition, Preussisch Oldendorf, Schutz, 1971, pp. 417.

[5] Ilse Gudden-Lüddeke, Recht auf Heimat niemals aufgeben (Never Give up the Right to the Homeland), in Pommersche Zeitung, 5 August 1995, p. 1.

[6] Maximilian Czesany, op. cit., p. 40.

[7] Ost-Dok. Vol. 2, No.7, p. 85.

[8] Ost-Dok. Vol. 2, No. 48, pp. 6.

[9] Ost-Dok. Vol. 2, No. 48, p. 2.

[10] Heinz Schön, ‘Die Fahrt in die Katastrophe’ (Journey Into Catastrophe), in Deutsche Militärzeitschrift , No. 24/2001, p. 67.

[11] Ost-Dok. Vol. 2, No. 44, p. 197.

[12] Ost-Dok. Vol. 2, No. 2, p. 80.

[13] Ost-Dok. Vol. 2, No. 21, p. 1074.

[14] Ost-Dok. Vol. 2, No. 36, pp. 48.

[15] Ost-Dok. Vol. 2, No. 23, p. 237.

[16] Ost-Dok. Vol. 2, No. 44, p. 174.

[17] Ost-Dok. Vol. 2, No. 23, p. 238.

[18] Ost-Dok. Vol. 2, No. 23, p. 239.

[19] See in particular Erich Kern & Karl Balzer, Alliierte Verbrechen an Deutschen. Die verschwiegenen Opfer (Allied Atrocities Committed Against Germans: The Hidden Victims), 2nd edition, Preußisch Oldendorf, Schütz, 1982.

[20] Ibid., p. 116 and p. 232.

[21] Ost-Dok. Vol. 1, No. 195, p. 165.

[22] Ost-Dok. Vol. 2, No. 243, p. 26.

[23] Ost-Dok. Vol. 2, No. 7, p. 20.

[24] Ost-Dok. Vol. 2, No. 22, p. 155.

[25] Ost-Dok. Vol. 2, No. 21, p. 716.

[26] Ost-Dok. Vol. 2, No. 21, p. 719.

[27] Wilfried Ahrens, Verbrechen an Deutschen. Dokumente der Vertreibung (Atrocities Committed Against Germans. Documents of the expulsion), 3rd edition, Bruckmühl, Ahrens, 1999, p. 25.