by Ragnar Redbeard

The Declaration of Independence commences by proclaiming an unctuous falsehood, a black, degrading self-evident lie—a lie which no one could possibly believe but a born fool. With insolent effrontery it brazenly proclaims as ‘a self evident truth’ that ‘all men are created equal’ and that they are ‘endowed,’ by their ‘Creator’ with certain ‘inalienable’ rights—rights which it thereupon proceeds to define in canting phraseology, imbecile and florid as it is false.

Indeed the mock-heroic preamble of this rhetorical pronunciamento is but a cunningly constructed piece of blague deliberately intended to deceive and betray. It consists of a patchwork of plagiarized catchwords, annexed wholesale from the ravings of seventeenth-century Levellers, crazed puritanic Mattoids and eighteenth-century cretinous French Jacobins—all mixed up and jumbled together with a long rigmarole of semi-meaningless pretty phrases, culled mostly from an old time melodrama.

The Declaration of Independence has less real meaning for present conditions than a bottled-up Indian war-whoop of the same period would have, if uncorked now. It is a back-number, musty, high smelling, and worm-eaten: only fit for the walls of a museum or the brain-cells of a daft philosopher.

Its ethical and most of its political conclusions are shams, deceptions, and cold-blooded dishonesties—incandescent Lies—glorified, belauded, printed in letters of gold, but nevertheless—Lies.

Indeed it has always been considered a piece of amusing mockery by those who really understood the secret intent for which it was originally constructed: viz:—as a lasso for the bellowing Herds, that, about one hundred years ago were beginning to run wild, and escape from their herdsmen, and herdsmen’s stock-whip, in this (then) boundless New World.

To all contemporary demagogues, the high-sounding phraseology of the ‘Declaration’ is as honey from paradise. Everywhere its seductive abstractions are the Avatars of anarchism, communism, republicanism, and scores of other zymotic convulsionisms. Why then should sane men continue giving lip-service to this subtle deception? Why should they, by their silence, acquiesce in the malefic efforts of organic weaklings, a mythical airy being who roams about Eternity manufacturing things out of no-things—a fable (instigated by prattlers of a false philosophy) to enforce by electioneering mass-pressure an impossible and hideous Equality Ideal?

Every national appeal is now made, not to the noblest and the best, but to the riff-raff—the slave-hordes—who possess less intelligence than night-owls. All that is brave, honourable, heroic, is ignored tacitly, for fear of offending the deified Herd—‘the Majority’. ‘Equality of conditions’ is its debasing shibboleth and verily he who has temerity enough to spit upon Equality is liable to be horned to death.

The ‘Voice of the People’ can only be compared to the fearsome shrieks of agony that may now and then be heard, issuing forth from the barred windows of a roadside madhouse. ‘The voice of God!’ Alas! Alas!

There are two methods whereby masterful ambitious men may hold any population in a state of ordered subjectivity. The first and by far the most honourable method is through an irresistible and highly-trained standing army, ready to deploy anywhere; with mechanical precision at a telegraphic nod in order to lay down the Law at the cannon’s mouth and sweep away all dangerous opposition.

The second and cheaper method is, first of all to inoculate those intended to be exploited with some poisonous political soporific, superstition [emphasis by Ed.], or theoria; something that operating insidiously, hypodermically, may render them laborious, meek, and tractable.

The latter plan has ever proved itself most effective because Aryan populations that would fight to the last gasp against undisguised military despotism, may be induced to passively submit to any indignity or extortion, if their brains are first carefully soaked in some abstract lie.

At the period of the war of Independence, North America was far too wide, far too sparsely settled, and far too poor in concentrated wealth to be effectively ruled and plundered upon the standing army principle: either by King George or the successful Junta of power-wielding revolutionists.

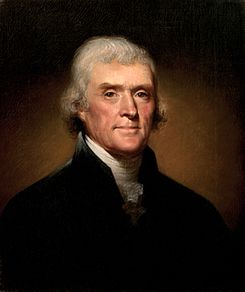

Hamilton, Hancock, Jefferson, Adams, Madison, Henry, and all the vested material interests that stood a solid phalanx behind those voluble patriots cast about for some safer method of ruling the minds of the uninformed but extremely valorous yeomanry, backwoodsmen and mountaineers.

After mature consideration they determined to lull and lure the armed peasantry back again into a condition of blissful somnolence, by instilling into their newly aroused minds, false but seductive political Idealisms, as subtle supplements to the fallacious, and equally delusive, (but pre-existent) religionisms and moralisms. This cunning plot worked like a charm, for Equity of Rights seemed to puritanic minds the logical outcome of that other hoary old lie—‘Equality before God’. [emphasis by Ed.]

Thereupon the sword of power, that conquered on the battlefield, was carefully hidden away out of sight and ‘constitutionalism’ invoked to aid in the re-harnessing of the conquerors of Cornwallis, by their new masters. The old systems of jurisprudence and government (founded on naked force) were cleverly retained even amplified and at the same time the white skinned populations were cunningly proclaimed ‘free and equal.’ Never having enjoyed genuine personal freedom (except on the Indian border) being for the most part descendants of hunted-out European starvelings and fanatics, (defeated battlers) they now stupidly thought that they had won freedom at last by the patent device of selecting a complete outfit of new tax-gatherers every fourth year.

When we look back upon the childlike faith in constitutionalism, displayed by our revolutionary Fathers together with their infantile republican specifics for the redemption of mankind, we cannot help smiling. At every general election, since 1776, Americans have voted solidly for increasing the despotic authority of their elective rulers and task-masters. Personal liberty is very nearly unknown (except in the newspaper) and any citizen who dares to think in direct opposition to the dogma of the Majority does so at the risk of his life, if he thinks too loudly.

Despotism, if it is to be overthrown, must be fought with its own weapons, and the vilest of Despotisms are ever founded upon Majority Votes.

Many years after the ‘Declaration’ was issued, our written Constitution was constructed with much voluble sophistry and mimic strife. That document, considered as a whole, is the most cunningly worded and at the same time most terrible instrument of Government and Mastership that any Anglo-Teutonic tribe has ever yoked itself up under. Pretending to ‘grant’ liberty and self-government, it practically annihilates both. Under the show of ‘guaranteeing’ personal independence and civil rights, it has organized an elective tyranny; wherein the mob-monarch possesses more arbitrary authority than any dynastic despot since the days of Darius or Balschazzar.

Under the hypnotic spell of a ‘free and equal’ dream, Americans have been hustled into a convict-prison of laboriousness to piratical masters a thousand times more terrible and more unyielding than any history can describe.

Even should America’s servile multitudes appeal to the arbitrement of physical force, they cannot possibly win. Possessing neither the strength, courage, brains, arms, money, nor leaders: they must be blown into eternal fragments by their master’s highly trained artillerists, and scientific destroyers.

The citadel of Power is now consolidated and prepared with the most improved armaments to repel any assault, no matter how well sustained. The nation is intersected in all directions, with iron highroads and splendid waterways, whereon armies and navies may be moved from city to city, with facility and dread effect. The War of Secession (or rather the war for the annihilation of self-government) demonstrated conclusively that a centralized authority, resting on herd-votes of the vulgar and fanatic is (in practice) military absolutism. There is no other Power in the land that can effectively hold it in check. The Czar of Russia possesses less actual authority than our Federal Government. With a standing army in the hollow of its hand, it can do exactly as it pleases, i.e. if it can collect enough revenue to purchase ‘statesmen’ and pay the salaries of its praetorian cohorts.

Most Americans are only now beginning to perceive these things, but they were foreseen, (and also foretold in part) by clear-sighted individuals before the Constitution itself was formally Enthroned.

What is viler than a government of slaves and usurious Jews? What is grander than a government of the Noblest and the Best—who have proved their fitness on the plains of death?

Cromwell and his Ironsides—Cæsar and his Legions shall be born again; and the thunderous tread of Sulla’s fierce destroyers shall roll and rumble amid the fire and glare and smoke of crumbling constitutionalisms: ‘as it was in the beginning, is now, and ever shall be’—warfare without end.

Yawping politicians may harangue base city mobs of hirelings and Christlings with ‘Alas, poor Yorick!’ rhapsody, as if struggle and strife were the evil of all evils. Figures of speech, however, cannot breathe the breath of life into feline philosophies that never have had the slightest foundation in Fact. The survival of the Fittest—the Toughest is the logic of events and of all time. They who declare otherwise are blind. The chief point is this: that Fitness must honestly demonstrate itself not by ignoble theft and theory but by open conflict as per Darwin’s law of battle.