Classical and modern

Enlightenment philosophers are given credit for shaping liberal ideas. Thomas Hobbes attempted to determine the purpose and the justification of governing authority in a post-civil war England. Employing the idea of a state of nature—a hypothetical war-like scenario prior to the State—he constructed the idea of a social contract which individuals enter into to guarantee their security and in so doing form the State, concluding that only an absolute sovereign would be fully able to sustain such a peace.

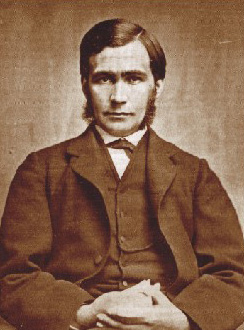

John Locke, while adopting Hobbes’s idea of a state of nature and social contract, nevertheless argued that when the monarch becomes a tyrant, that constituted a violation of the social contract, which bestows life, liberty, and property as a natural right. He concluded that the people have a right to overthrow a tyrant. By placing life, liberty and property as the supreme value of law and authority, Locke formulated the basis of liberalism based on social contract theory.

To these early enlightenment thinkers securing the most essential amenities of life—liberty and private property among them—required the formation of a “sovereign” authority with universal jurisdiction. In a natural state of affairs, liberals argued, humans were driven by the instincts of survival and self-preservation, and the only way to escape from such a dangerous existence was to form a common and supreme power capable of arbitrating between competing human desires. This power could be formed in the framework of a civil society that allows individuals to make a voluntary social contract with the sovereign authority, transferring their natural rights to that authority in return for the protection of life, liberty, and property.

These early liberals often disagreed about the most appropriate form of government, but they all shared the belief that liberty was natural and that its restriction needed strong justification. Liberals generally believed in limited government, although several liberal philosophers decried government outright, with Thomas Paine writing that “government even in its best state is a necessary evil”.

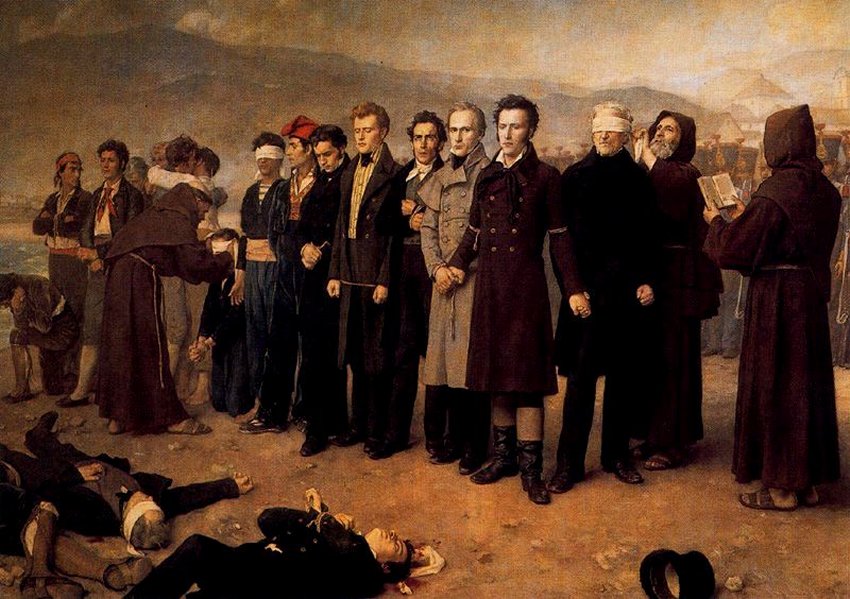

As part of the project to limit the powers of government, various liberal theorists such as James Madison and the Baron de Montesquieu conceived the notion of separation of powers, a system designed to equally distribute governmental authority among the executive, legislative, and judicial branches. Governments had to realize, liberals maintained, that poor and improper governance gave the people authority to overthrow the ruling order through any and all possible means, even through outright violence and revolution, if needed.

Contemporary liberals, heavily influenced by social liberalism, have continued to support limited constitutional government while also advocating for state services and provisions to ensure equal rights. Modern liberals claim that formal or official guarantees of individual rights are irrelevant when individuals lack the material means to benefit from those rights and call for a greater role for government in the administration of economic affairs.

Early liberals also laid the groundwork for the separation of church and state. As heirs of the Enlightenment, liberals believed that any given social and political order emanated from human interactions, not from divine will. Many liberals were openly hostile to religious belief itself, but most concentrated their opposition to the union of religious and political authority, arguing that faith could prosper on its own, without official sponsorship or administration by the state.

Beyond identifying a clear role for government in modern society, liberals also have obsessed over the meaning and nature of the most important principle in liberal philosophy: liberty. From the 17th century until the 19th century, liberals—from Adam Smith to John Stuart Mill—conceptualized liberty as the absence of interference from government and from other individuals, claiming that all people should have the freedom to develop their own unique abilities and capacities without being sabotaged by others. Mill’s On Liberty (1859), one of the classic texts in liberal philosophy, proclaimed that “the only freedom which deserves the name, is that of pursuing our own good in our own way”. Support for laissez-faire capitalism is often associated with this principle, with Friedrich Hayek arguing in The Road to Serfdom (1944) that reliance on free markets would preclude totalitarian control by the state.

Beginning in the late 19th century, however, a new conception of liberty entered the liberal intellectual arena. This new kind of liberty became known as positive liberty to distinguish it from the prior negative version, and it was first developed by British philosopher Thomas Hill Green. Green rejected the idea that humans were driven solely by self-interest, emphasizing instead the complex circumstances that are involved in the evolution of our moral character. In a very profound step for the future of modern liberalism, he also tasked society and political institutions with the enhancement of individual freedom and identity and the development of moral character, will and reason and the state to create the conditions that allow for the above, giving the opportunity for genuine choice. Foreshadowing the new liberty as the freedom to act rather than to avoid suffering from the acts of others, Green wrote the following:

If it were ever reasonable to wish that the usage of words had been other than it has been… one might be inclined to wish that the term “freedom” had been confined to the… power to do what one wills.

Rather than previous liberal conceptions viewing society as populated by selfish individuals, Green viewed society as an organic whole in which all individuals have a duty to promote the common good. His ideas spread rapidly and were developed by other thinkers such as L.T. Hobhouse and John Hobson.

In a few years, this New Liberalism had become the essential social and political program of the Liberal Party in Britain, and it would encircle much of the world in the 20th century. In addition to examining negative and positive liberty, liberals have tried to understand the proper relationship between liberty and democracy. As they struggled to expand suffrage rights, liberals increasingly understood that people left out of the democratic decision-making process were liable to the tyranny of the majority, a concept explained in Mill’s On Liberty and in Democracy in America (1835) by Alexis de Tocqueville. As a response, liberals began demanding proper safeguards to thwart majorities in their attempts at suppressing the rights of minorities.

Besides liberty, liberals have developed several other principles important to the construction of their philosophical structure, such as equality, pluralism, and toleration. Highlighting the confusion over the first principle, Voltaire commented that “equality is at once the most natural and at times the most chimeral of things”. All forms of liberalism assume, in some basic sense, that individuals are equal.

In maintaining that people are naturally equal, liberals assume that they all possess the same right to liberty. In other words, no one is inherently entitled to enjoy the benefits of liberal society more than anyone else, and all people are equal subjects before the law.

Beyond this basic conception, liberal theorists diverge on their understanding of equality. American philosopher John Rawls emphasized the need to ensure not only equality under the law, but also the equal distribution of material resources that individuals required to develop their aspirations in life. Libertarian thinker Robert Nozick disagreed with Rawls, championing the former version of Lockean equality instead.

To contribute to the development of liberty, liberals also have promoted concepts like pluralism and toleration. By pluralism, liberals refer to the proliferation of opinions and beliefs that characterize a stable social order. Unlike many of their competitors and predecessors, liberals do not seek conformity and homogeneity in the way that people think; in fact, their efforts have been geared towards establishing a governing framework that harmonizes and minimizes conflicting views, but still allows those views to exist and flourish.

For liberal philosophy, pluralism leads easily to toleration. Since individuals will hold diverging viewpoints, liberals argue, they ought to uphold and respect the right of one another to disagree. From the liberal perspective, toleration was initially connected to religious toleration, with Spinoza condemning “the stupidity of religious persecution and ideological wars”. Toleration also played a central role in the ideas of Kant and John Stuart Mill. Both thinkers believed that society will contain different conceptions of a good ethical life and that people should be allowed to make their own choices without interference from the state or other individuals.