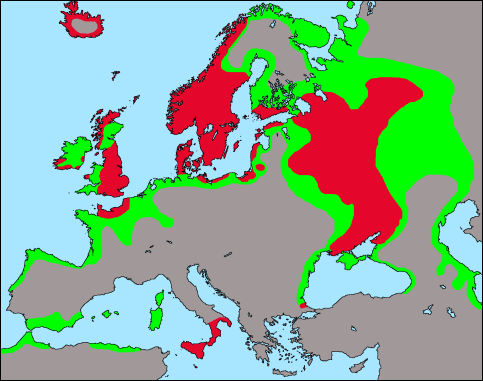

The Danelaw and the main areas of Viking settlement in Great Britain. Apart from the designated areas, the entire coast was strongly influenced by Scandinavia.

The Danelaw and the main areas of Viking settlement in Great Britain. Apart from the designated areas, the entire coast was strongly influenced by Scandinavia.

For a time, the Vikings made England a Danish kingdom. The Anglo-Saxons under King Alfred the Great, Germanics like the Vikings, engaged with them in a war in which the Vikings were confined to the north of England, in a kingdom called Danelaw (‘Danish law’), where Nordic paganism ruled and where there was a wide colonisation by Viking families, to such an extent that they left many words in the English vocabulary. Some historians have called it the ‘other England’ parallel, the ‘Scandinavian England’. Here, the Vikings established capital in Jorvik (York) and devoted themselves to rooting rather than looting, establishing farms, fields and trading centres.

Both the Vikings and the Normans fought over England. The war broke out when King Harold of England, Anglo-Saxon, had to face first with King Harald of Norway and then with King William the Conqueror of Normandy, who fought for the throne. The Anglo-Saxons of Harold confronted the Norwegians of Harald Hardrada (the last Viking king ‘of the old school’) at the Battle of the Stamford Bridge. Having defeated Harald, the battered Anglo-Saxon troops of Harold moved some 360 kilometers from Yorkshire (north of England) to Sussex (south of England), where William awaited them with fresh Norman troops. Exhausted Anglo-Saxon troops clashed with the Normans in the famous Battle of Hastings (1066). For the lack of a good cavalry and because many left the security of the wall of shields and spears to persecute the Norman knights who retired to reload, the Anglo-Saxons lost. Harold died with his skull pierced by an arrow that entered his eye. It was a tragedy for England.

The ‘Normans’ (really Frenchified Danish) imported the French language, polluting the Anglo-Saxon and stripping it of its most Germanic resonances. French became the language of the new Norman court, and the Anglo-Saxon—that is, Old English—the language of the commoners and the dispossessed aristocracy.

England was also infected with the Eastern mentality. Its focus of attention and cultural relations went from Denmark, northern Germany and Scandinavia, to France and the Vatican, and in this sense there is no doubt that even a Viking triumph would have been better.

The Normans imported, in addition, a feudal serfdom of Christian type (that had sense in places where the Germans constituted a minority aristocracy, but not in England, where most of the population was of Germanic origin), sweeping the old Saxon law, so hated by the Church, and that only remained in the county of Kent, which had been the place where the first Anglo-Saxons landed (specifically the Jutes, from Denmark) in the 5th century, and where the Anglo-Saxon Germanic tradition was perhaps stronger and more rooted. However, the Normans undoubtedly brought beneficial innovations: large stone castles with moats and the spirit of the new cavalry.

The Anglo-Saxons, in any case, were not going to resign themselves to that situation, and many of their aristocrats, leading their people, took part in a hidden resistance against the ‘Norman invasion’, which was nothing but a French invasion. The very legend of Robin Hood refers to the struggle between Anglo-Saxons and Normans, in which an Anglo-Saxon männerbund, headed by a Saxon nobleman, retires to the forest and carries out ‘guerrilla warfare’ against the occupation.

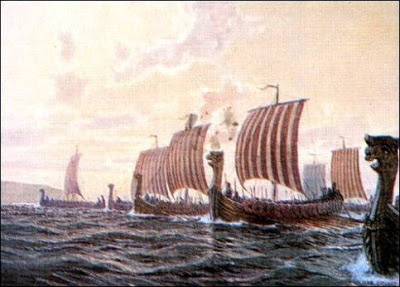

The Viking expansion was so immense that they have even found Buddha statuettes in Scandinavian tombs. Not without well-founded reasons, some authors, such as the Frenchman Jacques de Mahieu, have placed the Vikings at the base of aristocracies in places as distant as Peru and Mexico, and hence strange cases such as Quetzalcoatl, Kukulkan, Ullman or Viracocha, pre-Columbian gods with European features (such as the beard, white skin, light hair or blue eyes).

Of the Scandinavian nationalities, the Norwegians tended to explore Iceland, Greenland and America; the Danes were concentrated in England, Scotland, Germany, France and Ireland, and the Swedes devoted themselves above all to their adventures in the East, including Finland, Russia, wars against Khazars and Tartars and their exploits in the Islamic and Byzantine world.

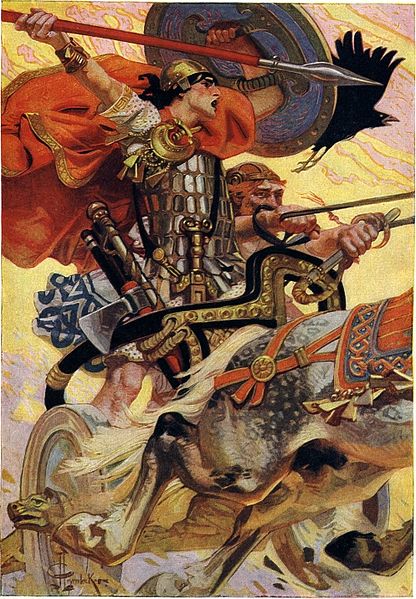

Non-Vikings considered the berserkers as the ultimate expression of the northern rage that spread like wildfire across Europe.

The same archetypal image of the bloodthirsty Viking that fights half-naked and kills indiscriminately, corresponds more to the berserker than to the ordinary Viking warrior. The fame and prestige of the berserkers in the North were enormous. They were bodyguards in many royal courts, including that of King Harald ‘Beautiful Hair’ of Norway. King Hrolf Kaki of Denmark sent his twelve berserkers to Adils of Sweden to help him in his war against Norway. After the Viking military campaigns, when casualties were counted, the military captains did not even bother to count the berserkers, since they assumed they were invincible after uttering spells that made them invulnerable to iron and fire, or that they were capable to disable the enemy’s weapons with their eyes.

Such fame came to the East, in such a way that the Emperor Constantine of Byzantium—a powerful man with many means, and who wanted the best—hired a select personal guard that was composed exclusively of Swedish berserkers. They were known as the ‘Varangian Guard’. (Over time, the guard would be so full of Anglo-Saxon warriors that it would become known as ‘English guard’.) As Constantine wrote, these men sometimes performed the ‘Gothic dance’, dressed in animal skins and totemic masks.

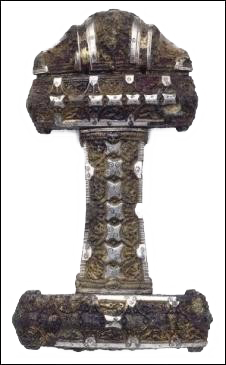

(Left, the Varangian Guard, known as pelekiphoroi phrouroi, ‘guardians armed with axes’, stood out gloriously in Constantinople or Miklagard for the Scandinavians.) Scandinavian paganism had preserved a healthy shamanism, deeply related to Nature and Asgard, the heaven of the gods. According to Germanic mythology, fallen berserkers formed in the Valhala Odin’s honour guard, so in their earthly life they tried to reflect and ‘train’ that vocation by protecting numerous kings whose power figure was associated with Odin.

(Left, the Varangian Guard, known as pelekiphoroi phrouroi, ‘guardians armed with axes’, stood out gloriously in Constantinople or Miklagard for the Scandinavians.) Scandinavian paganism had preserved a healthy shamanism, deeply related to Nature and Asgard, the heaven of the gods. According to Germanic mythology, fallen berserkers formed in the Valhala Odin’s honour guard, so in their earthly life they tried to reflect and ‘train’ that vocation by protecting numerous kings whose power figure was associated with Odin.

The Varangian Guard became famous in a series of campaigns against the Muslims, in one of which the Varangians destroyed nothing more and nothing less than eighty cities. In each Viking army, the berserkers formed a group of twelve men. The other warriors had great respect and fear, and tried to stay well away from them, because they saw them as dangerous, unstable and unpredictable. The berserkers themselves were kept separate from the rest of the corresponding army, cultivating the ‘pathos of distance’.