Read what a well-known

Christian author says

about the historical Jesus

in sharp contrast

to the Christ of the dogma (here)

Category: New Testament

A chapter from Ian Wilson’s

Jesus: The Evidence

While some elements in the gospels are clumsily handled and suggest that their authors were far removed in time and distance from the events they are describing, others have a strikingly original and authentic ring. In some instances it is as if a second generation has heavily adulterated first-hand material. Support for such an idea exists, at least in the case of the Matthew gospel, in the form of a cryptic remark by the early Bishop Papias (c. 60-130 AD): ‘Matthew compiled the Sayings in the Aramaic language, and everyone translated them as well as he could.’

This has been interpreted as suggesting that all that Matthew might have done was make a collection, in his native Aramaic, of those sayings of Jesus that he had heard, a collection, perhaps in form at least, very like those discovered in the Nag Hammadi Thomas gospel. Someone else, perhaps several others, would then have translated them and adapted them for their own literary purposes. This might readily explain why the Matthew gospel bears his name without, at least in the form it has come down to us, ever having been written by him. The crunch question, though, is why this situation should have come about. Why should original eyewitness material, emanating from Jews who had actually spoken with Jesus and observed his doings, have been adulterated and effectively buried by what were probably Gentile writers of a later time?

The answer appears to lie in one event, the Jewish revolt of 66 AD, which had its culmination four years later in the sacking of Jerusalem, the burning of its Temple, and the widespread extermination and humiliation of the Jewish people.

As is historically well attested, in 70 AD the Roman general Titus returned in triumph to Rome, parading through the streets such Jewish treasures as the menorah (the huge seven-branched candelabrum of the Temple), and enacting tableaux demonstrating how he and his armies had overcome savage, ill-advised resistance from this renegade group of the Empire’s subjects, many of whom he had to crucify wholesale. At the height of the celebrations the captured Jewish leader, Simon bar Giora, was dragged to the Forum, abused and executed. In Titus’ honour Rome’s mints crashed out sestertii with the inscription JUDAEA CAPTA, and within a few years a magnificent triumphal arch was erected next to the Temple of Venus.

As is historically well attested, in 70 AD the Roman general Titus returned in triumph to Rome, parading through the streets such Jewish treasures as the menorah (the huge seven-branched candelabrum of the Temple), and enacting tableaux demonstrating how he and his armies had overcome savage, ill-advised resistance from this renegade group of the Empire’s subjects, many of whom he had to crucify wholesale. At the height of the celebrations the captured Jewish leader, Simon bar Giora, was dragged to the Forum, abused and executed. In Titus’ honour Rome’s mints crashed out sestertii with the inscription JUDAEA CAPTA, and within a few years a magnificent triumphal arch was erected next to the Temple of Venus.

♣

Wilson’s chapter continues for a couple of more pages, but what I have quoted is enough to give an idea of what are modern studies on the New Testament.

A chapter from Ian Wilson’s

Jesus: The Evidence

Surprisingly, despite having been dismissed by the Germans as very late and very Greek, the gospel which would seem, in part at least, to have the most authentically Aramaic flavour of all is that of John. The first shock to the nineteenth-century Germans, with their dismissive attitude towards the John gospel, came with the discovery and publication of the Rylands fragment. If a copy of the John gospel was in use in provincial Egypt around 125 AD, its original, if it was composed at Ephesus (and at least no-one has suggested it was written in Egypt), must have been written significantly earlier, probably at least a decade before 100 AD, as most scholars now recognize.

A second shock was the discovery of the much publicized Dead Sea Scrolls. Although generally thought to have been written by the Essenes, a Jewish sect contemporary with Jesus, they proved disappointingly to throw little new light on Jesus and early Christianity, at least in any direct way. The Scrolls contain no recognizable mention of Jesus, just as the Christian gospels, surprisingly, fail to refer to the Essenes. But the intriguing feature of the Scrolls is that their authors, undeniably full-blooded Jews, were using in Jesus’ time precisely the type of language and imagery previously thought ‘Hellenistic’ in John.

As is well known, the John gospel prologue speaks of a conflict between light and darkness. The whole gospel is replete with phrases such as ‘the spirit of truth’, ‘the light of life’, ‘walking in the darkness’, ‘children of light’, and ‘eternal life’. A welter of such phrases and imagery occur in the Dead Sea Scrolls’ Manual of Discipline. The John gospel’s prologue,

He was with God in the beginning. Through him all things came to be. Not one thing had its being but through him (John I: 2-3).

is strikingly close to the Manual of Discipline‘s

All things come to pass by his knowledge, He establishes all things by his design. And without him nothing is done (Manual II: 11).

This is but one example of a striking similarity of cadence and choice of words obvious to anyone reading gospel and Manual side by side.

Even before such discoveries Oxford scholar Professor F. C. Bumey and ancient historian A. T. Olmstead had begun arguing forcibly that the John gospel’s narrative element, at least, must originally have been composed in Aramaic, probably not much later than 40 AD. One ingenious researcher, Dr Aileen Guilding, has shown in The Fourth Gospel and Jewish Worship that the gospel’s whole construction is based on the Jewish cycle of feasts, and the practice of completing the reading of the Law, or Torah, in a three-year cycle.

That the gospel’s author incorporated accounts provided by close eyewitnesses to the events described is further indicated by detailed and accurate references to geographical features of Jerusalem and its environs before the city and its Temple were destroyed in 70 AD, after Roman suppression of the Jewish revolt which had broken out four years earlier. It is John who mentions a Pool of Siloam (John 9: 7), remains of which are thought to have been discovered in Jerusalem, and a ‘Gabbatha’ or pavement, where Pilate is said to have sat in judgement over Jesus (Chapter 19, verse 13). The Gabbatha is identified as a pavement now in the crypt of the Convent of the Sisters of Our Lady of Sion in Jerusalem, undeniably Roman, though not conclusively dating from the time of Jesus.

(To be continued…)

A chapter from Ian Wilson’s

Jesus: The Evidence

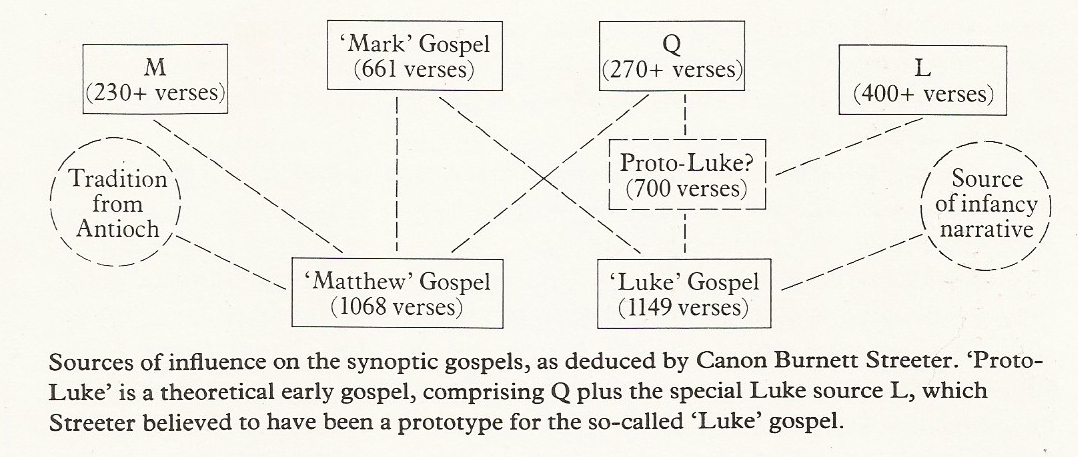

Bultmann died in 1976, at the age of ninety-two. A whole generation of modern New Testament scholars, among them his Marburg successor Werner Kiimmel, Bristol University’s Dennis Nineham, Harvard University’s Helmut Koester, and others, acknowledge an immense debt to him for introducing a whole new school of thought in theological research. Others, however, recognize that Bultmann went too far, and have challenged his rigid, unshakable attitudes: in Britain, while acknowledging that each gospel per se may have been written at second hand, several scholars have devoted great attention to the detection of underlying first-hand sources. Not long after Bultmann had begun his professorship at Marburg, across the Channel at Queen’s College, Oxford, a shy and retiring Englishman, Canon Burnett Streeter, quietly put the finishing touches to The Four Gospels: A Study in Origins.

By this time, thanks to both British and German theological re- search, it was already recognized that the authors of Matthew and Luke, in addition to drawing on the gospel of Mark, must have used a second Greek source, long lost, but familiarly referred to by scholars as ‘Q’ (from the German ‘quelle’, meaning source). It was even possible to reconstruct Q’s original content from passages in which Matthew and Luke bore close resemblance to each other, but not to Mark. While reaffirming this thinking, Streeter postulated at least two additional sources: ‘M’, which seemed to have provided material peculiar to the Matthew gospel, and ‘L’ which furnished passages exclusive to Luke. Streeter evolved a chart of the synoptic gospels’ possible interrelationship and dependence upon such sources. ‘M’ and ‘L’ may well have been written in Aramaic, the spoken language of Jesus and his disciples.

Streeter died in 1937, but his line of thought was developed by other major British theological scholars, among them Professor Charles Dodd, who went on to make his own special contribution to an understanding of the John gospel.

To this day the broad outlines of Streeter’s hypothesis remain the basis for much synoptic literary criticism. And the clues to underlying Aramaic sources are indeed there. In the Luke gospel, for instance, which includes ‘exclusives’ such as the parables of the Good Samaritan and the Prodigal Son, there occurs the following saying:

Oh, you Pharisees! You clean the outside of cup and plate, while inside yourselves you are filled with extortion and wickedness… Instead give alms from what you have and then indeed everything will be clean for you. (Luke II: 39-41).

‘Give alms’ appears to make no sense, yet it occurs in the very earliest available Greek texts. All becomes clear, however, when we discover that in Aramaic ‘zakkau’ (to give alms) looks very similar to ‘dakkau’ (to cleanse). That the original saying referred to ‘cleansing’ rather than ‘giving alms’ can be checked because Matthew includes a parallel passage in what we may now judge to have been the correct form: ‘Blind Pharisee! Clean the inside of cup and dish first so that the outside may become clean as well…’ (Matthew 23: 26). As has been remarked by Cambridge theologian Don Cupitt, this tells us more clearly than any amount of scholarship that whoever wrote Luke was not inventing his material, but was struggling with an Aramaic source that he was obviously determined to follow even if he did not fully under- stand it.

A similar misunderstanding is detectable in the Matthew gospel, notable for its remarkable ‘Sermon on the Mount’ passages, some of which, when translated from Greek into Aramaic, take on such a distinctive verse form that Aramaic must have been the language in which they were first framed. It is like translating the words ‘On the bridge at Avignon’ back into their original French.

(To be continued…)

A chapter from Ian Wilson’s

Jesus: The Evidence

If all these new discoveries seemed damaging enough, within two decades on to the scene at Germany’s Marburg University stepped Rudolf Bultmann (pic), acknowledged by many as this century’s greatest New Testament theologian, bringing with him a new and yet more devastating weapon, Formgeschichte or ‘form criticism’. This followed on from the work of Karl Ludwig Schmidt, a German pastor who had noted that a particular weakness of gospels such as Mark’s lay in the link passages, which appeared to have been invented to give an impression of continuity between one episode or saying and the next. Bultmann set his sights to trying to reconstruct what material, if any, might be authentic between the links. His approach was to try to assess each gospel element—birth story, miracle story, ethical saying, etc.—in order to establish whether it was original or had been borrowed from the Old Testament, or from contemporary Jewish thought, or merely invented to suit some particular theological line which early Christian preachers wanted to promulgate.

If all these new discoveries seemed damaging enough, within two decades on to the scene at Germany’s Marburg University stepped Rudolf Bultmann (pic), acknowledged by many as this century’s greatest New Testament theologian, bringing with him a new and yet more devastating weapon, Formgeschichte or ‘form criticism’. This followed on from the work of Karl Ludwig Schmidt, a German pastor who had noted that a particular weakness of gospels such as Mark’s lay in the link passages, which appeared to have been invented to give an impression of continuity between one episode or saying and the next. Bultmann set his sights to trying to reconstruct what material, if any, might be authentic between the links. His approach was to try to assess each gospel element—birth story, miracle story, ethical saying, etc.—in order to establish whether it was original or had been borrowed from the Old Testament, or from contemporary Jewish thought, or merely invented to suit some particular theological line which early Christian preachers wanted to promulgate.

For Bultmann anything that savoured of the miraculous—the nativity stories, references to angels, accounts of wondrous cures of the sick, and the like—could immediately be dismissed as prompted by the writer’s concern to represent Jesus as divine. Anything that appeared to fulfil an Old Testament prophecy—Jesus’ birth in Bethlehem, his entry into Jerusalem on a donkey, his betrayal, and much else—could be rejected as a mere attempt to represent his life as fulfilling such prophecies. If anything that Jesus was reported to have said could be traced to the general Jewish thinking of his time, then it was unacceptable as necessarily originating from him.

For instance, Jesus’ famous saying, ‘always treat others as you would like them to treat you; that is the meaning of the Law and the Prophets’ (Matthew 7: 12) may be found mirrored almost exactly in a saying of the great Jewish Rabbi Hillel, from less than a century before Jesus: ‘Whatever is hateful to you, do not do to your fellow-man. This is the whole Law [Torah]’. We cannot therefore be sure that this was ever said by Jesus. Similarly, in Mark’s gospel, Jesus is reported as telling a paralytic: ‘Your sins are forgiven’ (Mark 2:5). Jewish scribes were then said to have challenged Jesus’ right to offer such forgiveness, on the grounds that only God can forgive sins. According to Mark Jesus went on to cure the paralytic regardless. Bultmann argued that this story was probably invented by early Christians to bolster their own claim to be able to forgive sins.

By a series of deductions of this kind he concluded that much of what appears in the gospels was not what Jesus had actually said and done, but what Christians at least two generations removed had invented about him, or had inferred from what early preachers had told them. Not surprisingly, Bultmann’s approach left intact little that might have derived from the original Jesus—not much more than the parables, Jesus’ baptism, his Galilean and Judaean ministries and his crucifixion. Recognizing this himself, he condemned as useless further attempts to try to reconstruct the Jesus of history:

I do indeed think that we can now know almost nothing concerning the life and personality of Jesus, since the early Christian sources show no interest in either, are moreover fragmentary and often legendary.

Bultmann’s recourse was to the Lutheran concept of a Christ of faith, in his view a concept far superior to anything relying on works of history. And he and his colleagues seem to have happily accepted a divine Jesus while rejecting most of the historical evidence for his existence. Dr Geza Vermes, a leading present-day Jewish scholar, has neatly summarized the Bultmann position as having ‘their feet off the ground of history and their heads in the clouds of faith’.

(To be continued…)

A chapter from Ian Wilson’s

Jesus: The Evidence

In turn the John gospel came under similar scrutiny. The long speeches in fluent Greek attributed to Jesus were considered by German theologians to be Hellenistic in character, compatible with the gospel’s traditional provenance, the Hellenistic city of Ephesus in Asia Minor. Since even Church tradition acknowledged the John gospel to have been written later than the rest, it was thought to be most likely to date from close to the end of the second century. However, the one apparent crumb of comfort, that the Mark gospel, despite its geographical flaws, seemed to offer a less fanciful version of Jesus’ life than the rest, was in turn swept away with the publication, in 1901, of Breslau professor Wilhelm Wrede’s The Secret of the Messiahship.

Wrede argued powerfully that whoever wrote Mark tried to present Jesus as having deliberately made a secret of his Messiahship during his lifetime, and that most of his disciples failed to recognize him as the Messiah until after his death. While not necessarily giving this idea their full endorsement, most modern scholars acknowledge Wrede’s insight in establishing one fundamental truth—that even the purportedly ‘primitive’ Mark gospel was more concerned with theology, with putting over a predetermined theological viewpoint, than with providing a straight historical narrative.

Five years after Wrede’s publication, in a closely written treatise From Reimarus to Wrede, translated into English as The Quest for the Historical Jesus, Albert Schweitzer (pic), later to become the world-famous Lambarene missionary, summarized the work of his fellow German theological predecessors in these terms:

Five years after Wrede’s publication, in a closely written treatise From Reimarus to Wrede, translated into English as The Quest for the Historical Jesus, Albert Schweitzer (pic), later to become the world-famous Lambarene missionary, summarized the work of his fellow German theological predecessors in these terms:

There is nothing more negative than the result of the critical study of the life of Jesus. The Jesus of Nazareth who came forward publicly as the Messiah, who preached the ethic of the Kingdom of God, who founded the Kingdom of Heaven upon earth, and died to give his work its final consecration, never had any existence… This image has not been destroyed from without, it has fallen to pieces, cleft and disintegrated by the concrete historical problems which came to the surface one after another…

(To be continued…)

A chapter from Ian Wilson’s

Jesus: The Evidence

But the incursion into theology of the increasingly scientific outlook of the age was not to be checked so easily, particularly among Protestants. Under the professorship of the redoubtable Ferdinand Christian Baur, a prodigiously productive theologian who was at his desk by four o’clock each morning, Tübingen University in particular acquired a reputation for a ruthlessly iconoclastic approach to the New Testament, an approach which spread not only throughout Germany, but also into the universities of other predominantly Protestant countries. Traditionally the Matthew gospel had been regarded as the earliest of the four New Testament gospels, and it went virtually unquestioned that its author was Matthew, the tax-collector disciple of Jesus.

In 1835 Berlin philologist Karl Lachmann argued forcefully that the Mark gospel, simpler and more primitive, was the earliest of the three synoptics. Lachmann became swiftly followed by scholars Weisse and Wilke, later in the century the argument was taken up by Heidelberg theologian Heinrich Holtzmann, and by the end of the century Mark’s priority (even though not without challengers to this day) had become the most universally accepted theological discovery of the age. And this raised immediate problems concerning the authorship of Matthew. The Mark gospel, which from internal and external clues was almost certainly written in Rome, ostensibly offers the least claim of all the synoptics to eyewitness reporting. Traditionally, Mark is claimed to have been at best some sort of secretary or interpreter for Peter. The connection with Peter, if it existed at all, cannot have been that close, however, for the Mark gospel exhibits a lamentable ignorance of Palestinian geography. In the seventh chapter, for instance, Jesus is reported as going through Sidon on his way to Tyre to the Sea of Galilee. Not only is Sidon in the opposite direction, but there was in fact no road from Sidon to the Sea of Galilee in the first century AD, only one from Tyre.

Similarly the fifth chapter refers to the Sea of Galilee’s eastern shore as the country of the Gerasenes, yet Gerasa, today Jerash, is more than thirty miles to the south-east, too far away for a story whose setting requires a nearby city with a steep slope down to the sea. Aside from geography, Mark represents Jesus as saying, ‘If a woman divorces her husband and marries another she is guilty of adultery’ (Mark 10:12), a precept which would have been meaningless in the Jewish world, where women had no rights of divorce. The author of the Mark gospel must have attributed the remark to Jesus for the benefit of Gentile readers.

Since it is demonstrable that the author of Matthew drew a substantial amount of his material from the Mark gospel, is virtually impossible to believe that the original tax-collector Matthew, represented as having known Jesus at first hand, and having travelled with him, would have based his gospel on an inaccurate work whose author clearly had no such advantages. Bluntly, the original disciple Matthew could not have written the gospel that bears his name. Whoever wrote it must have been later than Mark. As a result of such reasoning, the German theologians began increasingly to date the origination of all three synoptic gospels to well into the second century AD.

(To be continued…)

Excerpted from a chapter from Ian Wilson’s Jesus: The Evidence

______ 卐 ______

This method is useful for showing up which episodes are common to all gospels, which are peculiar to a single gospel, the variations of interest or emphasis between one writer and another, and so on. It is immediately obvious that while Matthew, Mark and Luke have a great deal in common, describing the same ‘miracles’, the same sayings, essentially sharing a common narrative framework, the John gospel is a maverick, describing different incidents and devoting much space to lengthy, apparently verbatim speeches that seem quite unlike Jesus’ pithy utterances reported elsewhere. In about 1774 the pioneering German scholar Johann Griesbach coined the word ‘synoptic’ for the Matthew, Mark and Luke gospels, from the Greek for ‘seen together’, while that of John has become generally known as the Fourth Gospel. It has always been regarded as having been written later than the other three.

As different theologians pursued the underlying clues to the gospel writers’ psychology revealed by the parallel passage technique, so increasing scepticism developed, particularly in Germany during the early nineteenth century. There, a century earlier, a faltering start on a critical approach had been made by Hamburg University oriental languages professor Hermann Samuel Reimarus. In secret Reimarus wrote a book, On the Aims of Jesus and his Disciples, arguing that Jesus was merely a failed Jewish revolutionary, and that after his death his disciples cunningly stole his body from the tomb in order to concoct the whole story of his resurrection. So concerned was Reimarus to avoid recriminations for holding such views that he would only allow the book to be published after his death. His caution was justified.

Following in the critical tradition, in the years 1835-6 Tübingen University tutor David Friedrich Strauss (pic) launched his two-volume The Life of Jesus Critically Examined, making particularly penetrating use of the parallel passage technique. Because of the discrepancies he found, he cogently argued that none of the gospels could have been by eyewitnesses, but instead must have been the work of writers of a much later generation, freely constructing their material from probably garbled traditions about Jesus in circulation in the early Church. Inspired by the [idealistic] rationalism of the philosophers Kant and Hegel — ‘the real is the rational and the rational is the real’ — Strauss uncompromisingly dismissed the gospel miracle stories as mere myths invented to give Jesus greater importance. For such findings Strauss was himself summarily dismissed from his tutorship at Tübingen, and later failed, for the same reason, to gain an important professorship at Zürich.

Following in the critical tradition, in the years 1835-6 Tübingen University tutor David Friedrich Strauss (pic) launched his two-volume The Life of Jesus Critically Examined, making particularly penetrating use of the parallel passage technique. Because of the discrepancies he found, he cogently argued that none of the gospels could have been by eyewitnesses, but instead must have been the work of writers of a much later generation, freely constructing their material from probably garbled traditions about Jesus in circulation in the early Church. Inspired by the [idealistic] rationalism of the philosophers Kant and Hegel — ‘the real is the rational and the rational is the real’ — Strauss uncompromisingly dismissed the gospel miracle stories as mere myths invented to give Jesus greater importance. For such findings Strauss was himself summarily dismissed from his tutorship at Tübingen, and later failed, for the same reason, to gain an important professorship at Zürich.

(To be continued…)

A chapter from Ian Wilson’s

Jesus: The Evidence

It is perhaps a reflection of today’s emphasis on a Jesus of faith that most modern Christians, practising and non-practising, are quite unaware of the sort of conflicts that have riven the world of gospel studies during the last century or so.

Few realize, for instance, that despite the fact that the canonical gospels bear the names Matthew, Mark, Luke and John, these names are mere attributions, and not necessarily those of their real authors. The earliest writers who referred to the gospels significantly failed to mention names of authors, it being apparent that each gospel, both those surviving and those that have failed to survive, was originally designed as the gospel for a particular community. A canon of the four ‘recognized’ gospels only gradually came into general usage, at the same time acquiring associations with specific names from Christianity’s earliest years, though the connection was not necessarily legitimate. It should also be borne in mind that the earliest texts had none of the easy identification features that they bear now. Everything, without exception, was written in capital letters. There were no headings, chapter divisions or verse divisions, refinements which were not to appear until the Middle Ages. To make matters difficult even for the modern scholar, there was practically no punctuation or space between words.

Given such considerations it does not need anyone with a Ph.D. in theology to recognize that the Christian gospels can scarcely be the infallible works fundamentalists would have us believe. Examples of one gospel’s inconsistency with another are easy enough to find. While according to the Mark and Luke gospels Jesus stayed in Peter’s house, and afterwards healed the leper (Mark I: 29-45; Luke 4: 38 ff; Luke 5: 12 ff), according to Matthew (8: 1-4 and 14 ff) Jesus healed the leper first. While according to Matthew the Capernaum centurion spoke man-to-man with Jesus (Matthew 8: 5 ff), according to Luke (7: I ff) he sent ‘some Jewish elders’ and friends to speak on his behalf. Although according to Acts Judas Iscariot died from an accidental fall after betraying Jesus (Acts I: 18), according to Matthew he ‘went and hanged himself’ (Matthew 27: 5).

Disconcerting though such inconsistencies are, the fair-minded sceptic might be disposed to regard them as no worse than the sort of reporting errors which occur daily in modern newspapers. But New Testament criticism has gone much deeper than pointing out flaws of this order, there having been, in some quarters at least, a fashion for each new critic to be bent on outdoing his predecessors in casting doubt on the gospels’ authenticity.

The parallel passage technique

The first forays into understanding the men and facts behind the gospels began harmlessly enough. Many incidents concerning Jesus are related in two or more of the gospels, and an early research technique, still extremely valuable, was to study the corresponding passages side by side, the so-called ‘parallel passage’ technique.

Careful comparison of the three gospel passages above reveals a fundamental common ground the time of morning, the day of the week, the rolling away of the stone, the visit to the tomb by women. But it also discloses some equally fundamental differences which serve to tell us something about the gospel writers. The Mark author, for instance, speaks merely of ‘a young man in a white robe’, with no suggestion that this individual was anything other than an ordinary human being. In the Luke version we find ‘two men in brilliant clothes’ who appear ‘suddenly’. Although not absolutely explicit, there is already a strong hint of the supernatural. But for the Matthew writer, all restraints are abandoned. A violent earthquake has been introduced into the story, Mark’s mere ‘young man’ has become a dazzling ‘angel of the Lord… from heaven’, and this explicitly extra-terrestrial visitor is accredited with the rolling away of the stone.

(To be continued…)

It seems to me that the etiology of Western malaise is more complicated than what the average nationalist has imagined. While reading MacDonald’s first trilogy study on Jewry I thought that the etiology was, at least, threefold.

First: the hardware. As MacDonald and many others have pointed out, whites “have some unique characteristics such as individualism, abstract idealism and universal moralism” that are apparently genetic (precisely the characteristics that presently are being exploited by the tribe).

Second: the software. If the above is a problem in the hardware (something like whites being wired the wrong way when dealing with other races), these hardware characteristics were augumented after a Catholic cult, which means “universal” including all ethnic groups in the world, took over the Roman Empire.

Third: the virus. Paradoxically, once Christianity starts to be abandoned by the white people, our universalist-individualist-idealistic frame of mind, taken to its ultimate logic naturally results in liberalism, a “virus” of the mind operating within the white psyche.

If our diagnosis of the West’s darkest hour is correct, then the Jewish Problem is an epiphenomenon of the deranged altruism resulting from the secular fulfillment of universal Christian values. (Proof of it is that Muslims don’t allow the suicidal empowerment of Jews in their nations.) It also means that both our hardware wiring and our Judeo-Christian software must be understood before we can grasp the whys of the psycho-ethical structure that is preventing us from taking elemental action (e.g., disempowering the Jews). For the Christian that I was, and this is purely anecdotal (others may find different venues), the first step to understand the virus was starting to question the historicity of the gospel narratives.

If our diagnosis of the West’s darkest hour is correct, then the Jewish Problem is an epiphenomenon of the deranged altruism resulting from the secular fulfillment of universal Christian values. (Proof of it is that Muslims don’t allow the suicidal empowerment of Jews in their nations.) It also means that both our hardware wiring and our Judeo-Christian software must be understood before we can grasp the whys of the psycho-ethical structure that is preventing us from taking elemental action (e.g., disempowering the Jews). For the Christian that I was, and this is purely anecdotal (others may find different venues), the first step to understand the virus was starting to question the historicity of the gospel narratives.

Thus I typed many passages from Helms’ book in honor of Porphyry, the first man to write a prolegomena of what fifteen centuries later started to be called “higher criticism” of the Bible.