The NSDAP programme—for example point 13[1] with its attack on ‘trusts’—was ferociously anti-capitalist and so, as we have seen, was much of Hitler’s rhetoric. Despite Hitler ‘s willingness to moderate his message to business audiences, emphasizing his anti-French and anti-Bolshevik themes, business was not reassured. Paul Reusch, a major Ruhr baron, noting the Nazi nationalization plan, remarked that ‘we have no reason to support our own gravediggers’. The party remained dependent on donations from the Bavarian Reichswehr, either in cash or in kind in the form of weapons or vehicles, and from a motley group of smaller donors, mainly traders, retailers and small businessmen.

The NSDAP programme—for example point 13[1] with its attack on ‘trusts’—was ferociously anti-capitalist and so, as we have seen, was much of Hitler’s rhetoric. Despite Hitler ‘s willingness to moderate his message to business audiences, emphasizing his anti-French and anti-Bolshevik themes, business was not reassured. Paul Reusch, a major Ruhr baron, noting the Nazi nationalization plan, remarked that ‘we have no reason to support our own gravediggers’. The party remained dependent on donations from the Bavarian Reichswehr, either in cash or in kind in the form of weapons or vehicles, and from a motley group of smaller donors, mainly traders, retailers and small businessmen.

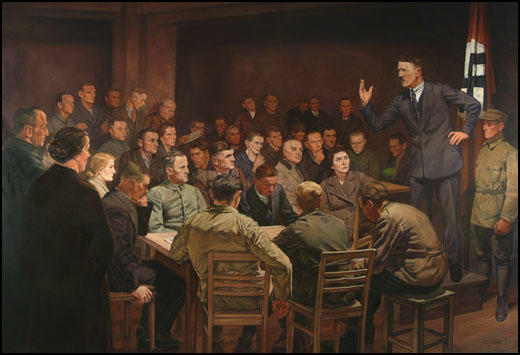

Given the shortage of funds, the growth of the party and especially its propagandistic reach was impressive. There were significant gains in membership: 4,300 by the end of 1921, and more than 20,000 a year later… There was a real quantum leap in early 1922, when Hitler regularly spoke to between 2,000 and 6,000 listeners in the larger beer halls. A high point was the Deutsche Tag in Coburg in October, which culminated in a massive brawl with hostile demonstrators…

The purpose of all this activity was not the creation of a party organization capable of winning elections, still less that of a force capable of mounting an armed challenge to the Weimar Republic. Instead, Hitler’s main aim remained the establishment of ideological coherence in the movement. ‘The final strength of a movement,’ he claimed in mid February 1922, lay ‘not in the number of its local groupings but in its internal cohesion’…

Hitler claimed that ‘there was no fruitful work to be done in parliament’, and that ‘individual National Socialists would be corrupted by the swamp of parliamentarism’.

Throughout the early 1920s, therefore, Hitler used his speeches to rehearse and develop his ideology. During this period his words—which were, of course, acts in themselves—were more important than his deeds. The recent defeat and its causes remained the central preoccupation. Hitler repeated his conviction that the war had been caused by an Anglo-American capitalist conspiracy. Sometimes, he attributed the ‘original sin’ to Britain, whose commercial and colonial ‘envy’ of the Reich had driven a ‘policy of encirclement’ against Germany, and whose press had vilified her before and during the war as a nation of Huns and barbarians. On other occasions, he targeted the United States. ‘Not least because the social welfare and the cultural development [of the German Empire] was a thorn in the eyes of the American trust-system,’ he thundered in March 1921, ‘we had to disappear from view.’ Hitler repeatedly contrasted ‘Germany’s social culture’ with American capitalism. He reserved particular scorn for US president Woodrow Wilson as the ‘agent of international high finance’…

Fighting France, and especially the British Empire, was bad enough, but what had ultimately tipped the scales was US intervention. This, Hitler was convinced, would have taken place with or without the U-boat war. Having previously been a ‘passive’ supporter of the Entente through the supply of armaments, the Americans intervened when Britain and France were on the verge of defeat in order not to lose the ‘billions’ which it was owed by the Allies. ‘America was called in,’ he claimed, ‘and the power of international big capital thereby became openly involved’…

___________

[1] Editor’s Note: ‘We demand nationalization of all businesses which have been up to the present formed into companies (trusts).’