2 Tort – Colín

The park that welcomed me

This game was played in the park where I played chess in the Colonia del Valle in Mexico City, very close to where I lived with my grandmother. This park welcomed me in my teens when I fled from extremely abusive parents and school. It was a different place than the public parks where the outcast underclass used to take refuge to play chess and dominoes. It’s true that when I was repudiated by my parents I found myself as marginalised as the underclass, but in Las Arboledas Park there was a cultural level very different from that of the parks with the tents in the centre of Mexico City. It was there, in this park for middle-class people, that I really learned to play chess.

This game was played in the park where I played chess in the Colonia del Valle in Mexico City, very close to where I lived with my grandmother. This park welcomed me in my teens when I fled from extremely abusive parents and school. It was a different place than the public parks where the outcast underclass used to take refuge to play chess and dominoes. It’s true that when I was repudiated by my parents I found myself as marginalised as the underclass, but in Las Arboledas Park there was a cultural level very different from that of the parks with the tents in the centre of Mexico City. It was there, in this park for middle-class people, that I really learned to play chess.

FRIENDLY GAME

Las Arboledas Park

(ca. 1985)

1 e4 e5

2 Bc4

This was my favourite move in the park. I won countless games with 1 PK4, PK4; 2 BB4, as it was written then in the descriptive notation (as opposed to the algebraic notation that I use in most of this book). The idea was not to play the hackneyed lines of the Bishop’s Opening, but the gambit that ensues after 2… NKB3; 3. NKB3, NXP; 4. NB3!? whose theory no one knew. In this game Marco Colín eluded the gambit and simply transposed to the Two Knights Defence, so he came out unharmed from the dangers of this opening.

2 … Nf6

3 Nf3 Nc6

4 d4

When I made this move Marco complained that it was a prepared book line. The advantage of friendly games over tournament games is that you can unleash your emotions; you can even curse and there is no rule against it.

4 … Nxe4

5 dxe5

Here Marco exclaimed: ‘Bishop takes pawn, check!’ in the sense that he had seen the threat. ‘Damn brother!’ Only Marco called me with the pleonastic nickname ‘El hermano brother.’

5 … Nc5

6 Nc3 Be7

7 Nd5 O-O

9 O-O Ne6

8 Nxe7 +

I remember that I was worried about the bishop on c5 and wanted to eliminate it as soon as possible.

8… Qxe7

10 c3 b6

11 Bb3 Bb7

12 Re1 Rd8

Since I wrote down this game from memory only when I got home, I don’t remember if the order of the last two moves was correct. Did I play the rook first and then the bishop?

13 Nd4 Rfe8?!

When Marco played this I was surprised. I thought that because of my next move he had to exchange knights. At postmortem he told me he didn’t want me to join my pawns. But he should’ve taken the knight (Kasparov says that when he manages to bring a knight to the f5-square he already feels won). As in the previous game, I didn’t use computer systems to analyse this game. What I write down here were the memories of what I was thinking during the game in the mid-eighties, without outside help.

14 Nf5 Qc5

15 Qh5!

If now 15… Nxe5; 16 Rxe5, winning.

17 … g6

16 Ch6 + Kg7

17 Qf3 Qe7

18 Qg3 Kh8

19 Ng4 d6

One of the Arboledas players, Antonio Galán, who had been watching the game, told me alone when we were walking in the park while Marco reflected: ‘NB6 and pélas!’ although I had already seen this move before he told me. In Mexico this expression is used when a person has been left out of something, for example, eliminated from a competition: ‘Pelas!’ Antonio used the expression in the sense that he saw the black’s defence collapsing. In Spain the pélas colloquialism means something very different: money, as in the neighbouring country to the north it’s colloquially said buck instead of dollar.

20 Nf6 Nxe5

Otherwise a very dangerous attack on the king would come.

21 Nxe8 Rxe8

22 Bxe6! Qxe6

It took me a while to reassess this new position. (Although clock games weren’t played in the park unless they were blitz games, this and others that I played with Marco, Antonio and Enrique Legorreta were virtual tournament games.) Marco then indicated that he intended to play 22…Ng7 if I hadn’t taken the knight from him.

23 Be3

The game is technically won, but this was a trap Marco missed.

23 … c5?

24 f4

Marco made an angry exclamation and shook his head. The interest that we both had invested in the game was considerable because we hadn’t played for a long time with each other.

24 … Nc6

Marco was still flustered and visibly pissed off when he made this last move.

25 Bd4 + Nxd4

26 Rxe6 Nxe6

27 f5!

If this one survived among the countless games I played in the park, it was because of something that caught my attention. As I noted in my diary many years ago: ‘I had always wanted to kill Marco with a queen sacrifice right in this position a few moves later. Synchronicity?’, referring to Jung’s theory. Although I am now sceptical of that theory, the coincidence is interesting: one of the reasons that prompted me to score this game.

27 … Ng7

28 f6 Nf5

29 Re1

I remember Marco’s shock when he saw this move.

29 … Be4

30 Qf4 d5

31 g4 Nh4

32 Qh6 Nf3 +

33 Kf2 Rg8

34 Re3

I thought about this a lot, making sure that after:

34 … Ne5

I immediately made the following pseudo-sacrifice of queen to surprise the old friend:

35 Qxh7 +

Marco removed both his king and my queen from the board as a sign that he was resigning. He was so outraged by the defeat that we barely commented on the postmortem, and at a fast pace he headed for the subway station División del Norte while, naively, I wanted to talk to him after not seeing him for so long. But to be fair I must say that the next day, after his severe moods he confessed to me ‘You played very well!’

Regardless of the game above, it hurts that other games that I played with Marco and those in the park have not been preserved. How I would like to have, for example, that ‘historic’ game in which, playing both blindfold chess, I beat Gerardo Brauer in 1978: a game that merited a bet between my admirers in the park and those of Gerardo. I would also like to be able to reproduce, at home, that five-hour game when I beat Enrique in front of his girlfriend, or those that I beat Gilberto Rangel in a match that he and I played at my grandmother’s house, or the Volga Gambits that with the black pieces I played against Fernando Pérez Melo until he devised a good reply to the defective gambit. (Although he came from the underclass, Fernando had a very good taste for art cinema. I remember that he liked Andrei Rublev when the Russian Embassy premiered it in Mexico.) Only Antonio took the trouble to transcribe some of the games he played in the park. Thanks to his initiative I was able, twenty years after it was played, to reproduce one of the games that Antonio played with Gilberto; although he didn’t want to give me the score sheet of another one where I beat him with white when, from attacking to his queenside, I suddenly switched to a kingside attack. Instead of reproducing his game with Gilberto that he provided me, I would like to say a few words about

This friend who never was

We men are supposed to be very tough, like the tough guys in Hollywood movies: that we don’t cry and that we face our problems alone. This code leads men to seek comfort in gambling, alcohol, a drug, or another artificial balm to alleviate the internal sting. Gilberto, one of the park’s children who threw himself the most on Caissa’s skirts, had a permanent scar on his face caused by a dish that his mother had thrown at him. His friend Roberto, a good-looking, fair-haired lad who also went to the park, had been raped by a priest of the Catholic church on Avenue Cuauhtémoc on the corner of Concepción Beistegui street.

I never knew of anyone who approached Gilberto to talk about the abuse he had suffered at home. The player is able to sit in front of his opponent for years without knowing anything about his life. The purpose of the chessboard between these tough guys is to function as a kind of isolation barrier, and I would like to confess what happened to me when I wanted to break that code of isolation between players. Like Gilberto, what I needed back then was a friend who could listen to me about the huge problem I had at home. But I had none, and when I dared to bring up the subject with Antonio he went to complain to the others that ‘we all have problems’, in the sense that my position was self-centred. As the gossip reached me, Antonio added that he was a friend of mine ‘just to talk about chess’.

If he really said that, he was wrong. I was not self-centred. The proof is that Antonio’s family problems with his brothers were not so serious as to prevent him from pursuing a career. Mine or Gilberto’s were so big that we were left without a profession. The fact that such an elementary reality, one of those that between women so well communicate with each other, is impossible to communicate between men speaks very badly of the player’s psychology, so well portrayed in Dostoevsky’s tale. Precisely because our society forbids us men to mourn, or to have an intimate confidant, Roger Bayde, another of our friends from the park, committed suicide. Like Gilberto, Roger had had a traumatic past with his mother since his childhood, but no one listened to him. Although I’m not sure, it seems to me that the Department of Psychiatry at UNAM, the university where Roger worked, prescribed him psychotropic drugs instead of offering him the ear that he so badly needed.

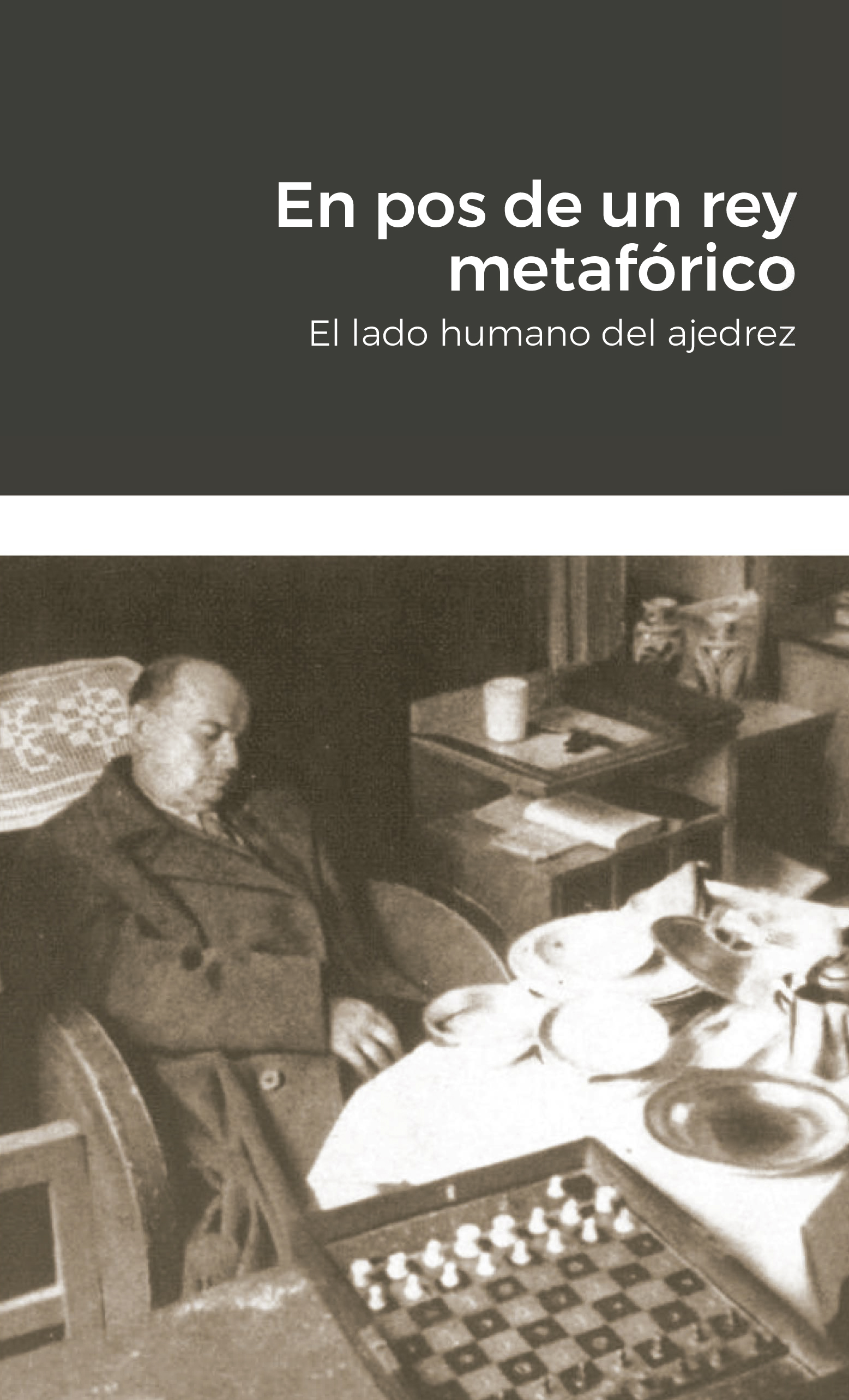

Roger’s story is not an isolated case in the troubled kingdom of Caissa. Iván used to visit the cabin whose photo appears in the Introduction. This friend became psychically disturbed due to parental abuse (once I spoke to him on the phone he exhibited all the symptoms of ‘word salad’: the peculiar way some people labelled as schizophrenic speak). On one occasion we saw how a man with a hat dragged him by the hair while taking him out of the cafe of the old Gandhi Bookstore: the only time I saw his father. If so he mistreated him in public, how could he not do it in private (his brother shot himself dead in front of his father)?

I could mention other cases of chess players who, like Iván, Roger, Gilberto and Fernando were beaten by their parents and their lives were shattered. But it is unnecessary. Rather, and although very belatedly, I would like to answer the friend who never was: What would I give so that there would be a little more communication between men. And a little less chess…