Preface of 2021

Although I have been a chess fan, I have only participated in one tournament duly endorsed by the International Chess Federation (FIDE in its French acronym) in 2004, which gave me a provisional rating of 2109 (the current world champion’s rating is 2847). However, after my racial awakening I cannot see my old hobby as I used to see it. Some facts from the life of world chess champion Mikhail Botvinnik (1911-1995), who won the chess crown just after the Holocaust of millions of Germans (read Tom Goodrich’s Hellstorm), will illustrate my current point of view.

Although I have been a chess fan, I have only participated in one tournament duly endorsed by the International Chess Federation (FIDE in its French acronym) in 2004, which gave me a provisional rating of 2109 (the current world champion’s rating is 2847). However, after my racial awakening I cannot see my old hobby as I used to see it. Some facts from the life of world chess champion Mikhail Botvinnik (1911-1995), who won the chess crown just after the Holocaust of millions of Germans (read Tom Goodrich’s Hellstorm), will illustrate my current point of view.

According to Soviet politician Nikolai Krylenko, Botvinnik exhibited the features of a true Bolshevik and Botvinnik’s celebrated student, Garry Kasparov, described his mentor as a staunch communist, a child of the Stalin regime. In his memoirs, Botvinnik himself acknowledged that he was lucky in life because his interests coincided with those of his society. ‘I am a Jew by blood, a Russian by culture and a Soviet by education’, he said.

Estonian Paul Keres may have won the crown after world champion Alexander Alekhine suddenly died in 1946. In fact, Alekhine had practically offered him the crown by allowing him to challenge him to a title match when Alekhine was already in full decline. Young Keres made the mistake of his life by rejecting the kind white glove. I would venture to claim that the outcome of the 1948 tournament, which crowned the ethnic Jew Botvinnik as Alekhine’s successor, was the logical conclusion of the ideological Judaization of the Soviet Union and Eastern Europe (read Aleksandr Solzhenitsyn’s 200 Years Together), and the degradation of Estonians in Stalin’s post-war society.

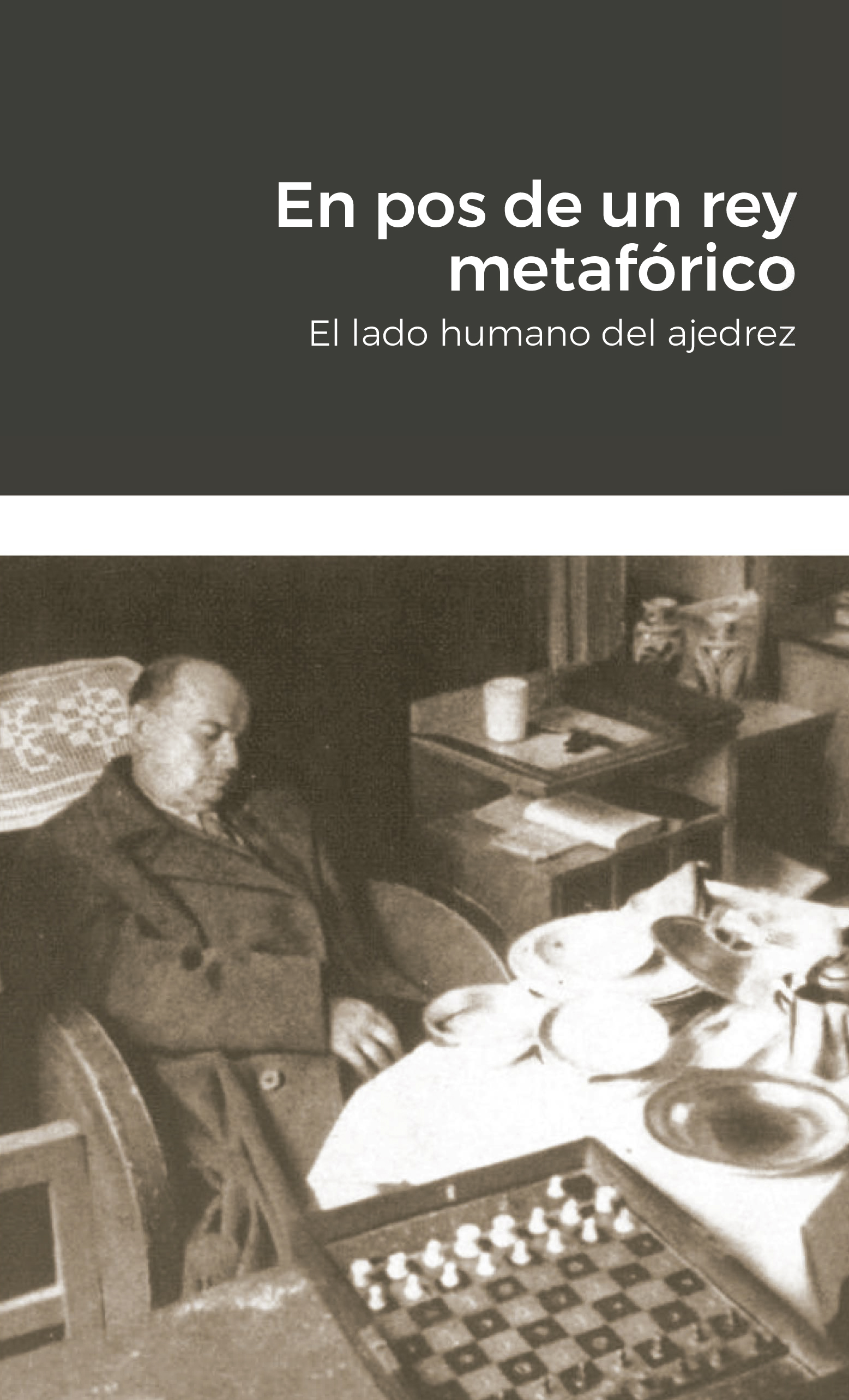

Alekhine was my idol when I was a teenager. He had belonged to the Russian aristocracy and in 1909 in Saint Petersburg he received from Tsar Nicholas II a beautiful vase of Sevres. It was the award for having won a national junior championship. It was Alekhine’s most prized possession, and when he decided to leave Russia due to the Red Terror, the vase was the only item he took with him. He even had it in his room the night he died in Portugal (see cover of the book above), fleeing to the westernmost country of Europe on accusations of having collaborated with the fascists. If the Europeans had been sane they wouldn’t have harassed him, as the fascists had been the only ones to face the red threat, unlike the Anglo-Saxons.

Interestingly, Kasparov, whose Jewish surname was Weinstein before changing it, confesses in his book about his predecessors that as a child he was Botvinnik’s favourite pupil. While his mentor played the role of teacher with other children, the former champion had regular contact with the young Garry for fourteen years—something that, Kasparov acknowledges, greatly helped him in his career to win the sceptre of chess. Life was difficult for him and his mother in those days, and Botvinnik did his best to help them and provided them with food stamps.

Interestingly, Kasparov, whose Jewish surname was Weinstein before changing it, confesses in his book about his predecessors that as a child he was Botvinnik’s favourite pupil. While his mentor played the role of teacher with other children, the former champion had regular contact with the young Garry for fourteen years—something that, Kasparov acknowledges, greatly helped him in his career to win the sceptre of chess. Life was difficult for him and his mother in those days, and Botvinnik did his best to help them and provided them with food stamps.

Currently the Norwegian Magnus Carlsen is the world chess champion, the sixteenth champion. All conventional lists of world chess champions begin with the Austrian Jew Wilhelm Steinitz. My list adds one more champion: the American Paul Morphy, as we will see in this book. To date, I am not aware of any list that reveals the ethnicity of six of the seventeen champions, if we add one more to the list starting with the number zero. The following dates indicate the year in which they conquered the world crown. Note that only one Latin American has conquered it:

0. Paul Morphy (1858) United States

1. Wilhelm Steinitz ✡(1886) Austria-Hungary

2. Emanuel Lasker ✡(1894) Germany

3. José Raúl Capablanca (1921) Cuba

4. Alexander Alekhine (1927) exiled in France

5. Max Euwe (1935) Holland

6. Mikhail Botvinnik ✡(1948) Soviet Union

7. Vasily Smyslov (1957) Soviet Union

8. Mikhail Tal ✡(1960) Soviet Union

9. Tigran Petrosian (1963) Soviet Union

10. Boris Spassky (1969) Soviet Union

11. Robert Fischer ✡(1972) United States

12. Anatoly Karpov (1975) Soviet Union

13. Garry Kasparov ✡(1985) Soviet Union

14. Vladimir Kramnik (2000) Russia

15. Viswanathan Anand (2007) India

16. Magnus Carlsen (2013) Norway

Seventeen years ago I wrote the book that appears below and circulated it to a couple of friends who love chess. Since then I have changed the way I saw the world, so I have modified some passages of the text. For example, on YouTube you can see an interview this year between chess grandmaster Hikaru Nakamura and Kasparov. The Japanese used the feminist slogan ‘close the gap’ with the former champion when saying that women would have to participate in chess tournaments in the same numerical proportion as men. Nakamura didn’t realise the biological impossibility of such a desire, as we recently demonstrated in On Beth’s cute tits (see our book list on page 3).

If I get to play other FIDE-endorsed tournaments next year, we’ll see how much my rating goes up, or down, compared to my rating the year I wrote this book…

C.T.

June 2021

4 replies on “The human side of chess, 1”

The book is not yet available on Lulu. When I finish its translation next month (I estimate 18 posts for this blog), the hard copy will be available in the language I wrote it.

I find it intriguing that Nakamura-a Mongoloid from a completely non-xtian culture-would desire such a thing as “closing the gap”. It makes sense for an Xtian or Jew to say that, but for a man from the same place where missionaries were slaughtered to prevent Xtian tentacles from converting Japan? That goes against the idea that feminism is always Xtian in origin. Unless Nakamura was converted or born into the Xtian religion, I cannot see why he would support feminism.

Nakamura is an American.

Having looked into this man, I now see that he is a mongrel. His American mother quite likely led him to believe that “there is no man nor woman in Jesus”. As virtually all Americunts at the time were either Xtians or Neo-Xtians, this is obvious.