by Eduardo Velasco

Middle Ages: Pax Mongolica

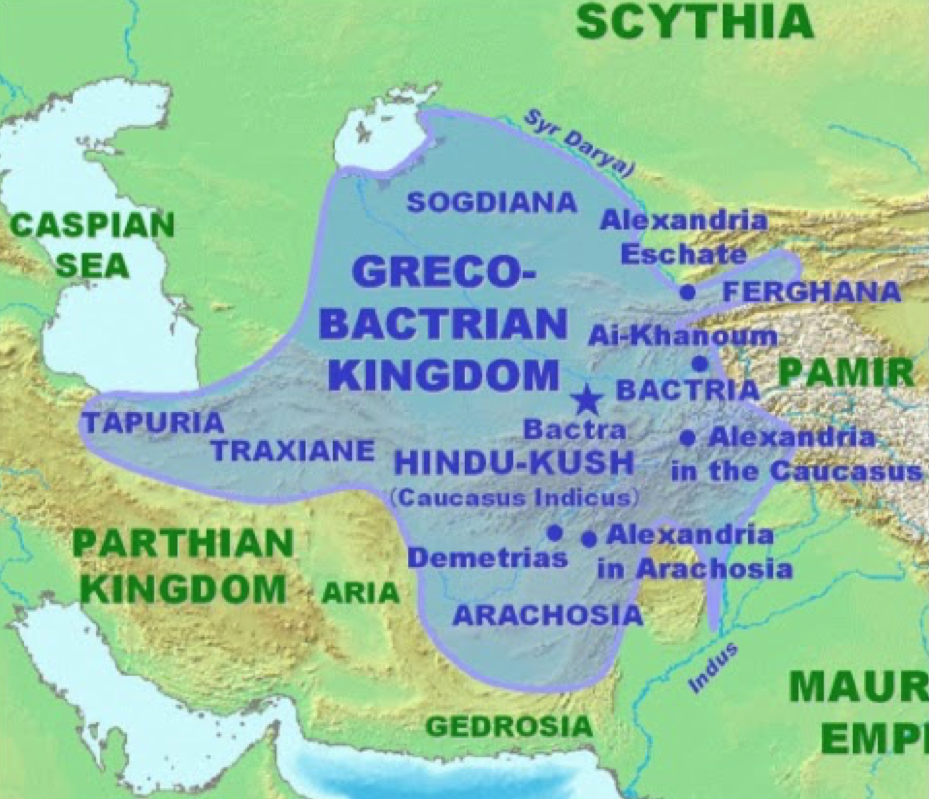

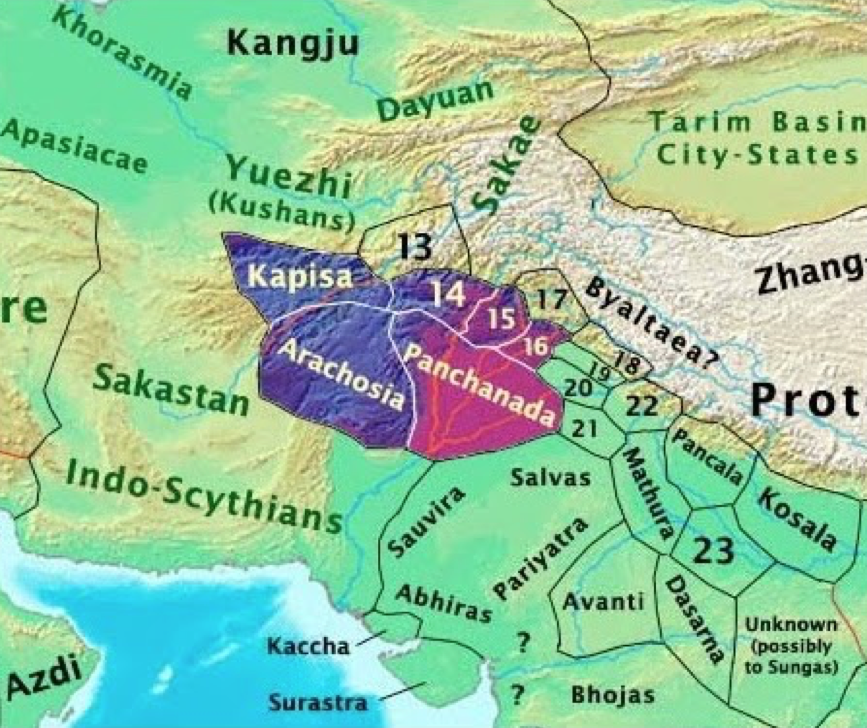

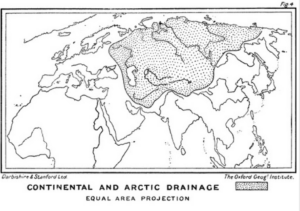

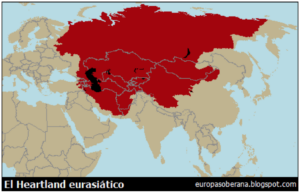

If initially Hindu and Bactrian traders had dominated the Silk Road trade, between the 5th and 8th centuries the Sogdians and, after the Muslim conquests, the Arabs and Persians would do so. At the western end of the route, Byzantium was the first European power to realise that the Heartland was a geopolitical reality to be taken into account. Alternating diplomacy and war with the peoples of the steppe (Avars, Pechenegs, Kipchaks and others), Constantinople could prolong its existence for a millennium after the fall of Rome.

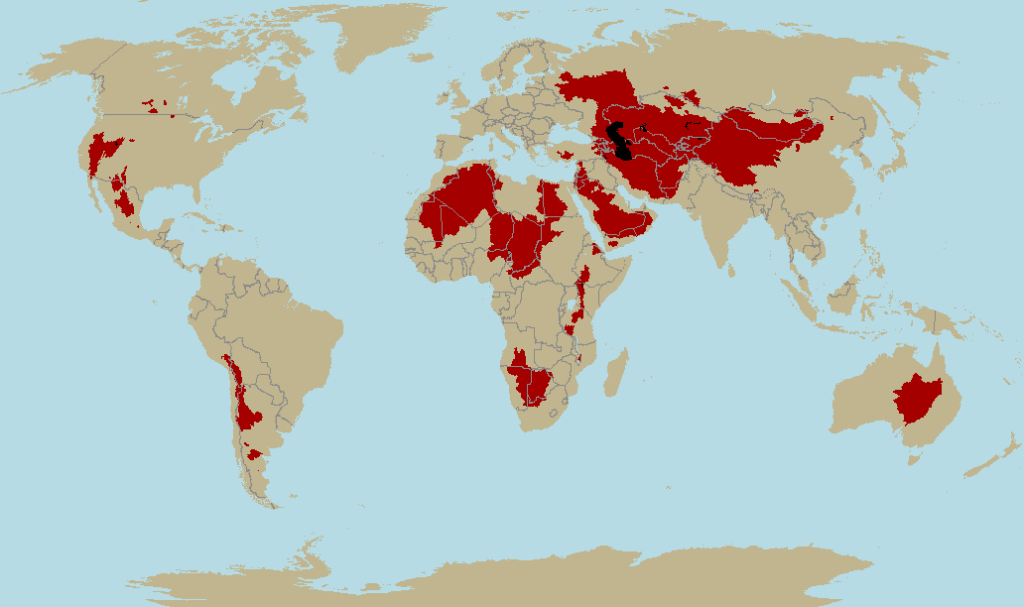

Closely intertwined with the history of Byzantium is that of the Varangians (as the Slavs called the Vikings of Sweden), who moved up the great Russian rivers from the Baltic to the Black Sea basin and allied with the Slavs in an attempt to defeat the Khazars—a steppe confederation in southern Russia that had adopted Judaism as its official religion and is probably the ancestor of much of Ashkenazi Jewry. The Varangians took Kiev, the southernmost of the cities on the Dnieper, which allowed them to maintain constant contact with Byzantium, and eventually conquered the Khazar capital, Sarkel, not far from present-day Volgograd. In doing so, they came to dominate the trade corridor where the Don and Volga rivers come closest, jumping from the Black Sea basin to the Caspian basin—thus to the Heartland—and establishing themselves as a sort of second Byzantine Empire to connect Europe with Asia. The history of the Russias begins, clustered around cities like Kiev, Novgorod, Vladimir, Suzdal, Pskov or Muscovy, in generally heavily forested territories, where the Orthodox faith will eventually prevail.

Red: areas subject to Viking colonisation. Green: areas subject to Viking influence. Russia was born as an intermediary between the Scandinavian and Byzantine worlds, just as Germania was born as an intermediary between the Scandinavian and Roman worlds. The Vikings, as the founders of the first Russian states, laid the foundations of the only power capable of dominating the Heartland in the long run and connecting it with Eastern Europe. Although the core of historic Russia was born in Kiev, it slowly moved northwards, passing through cities such as Smolensk, Novgorod, Vladimir, Suzdal, Moscow and St Petersburg.

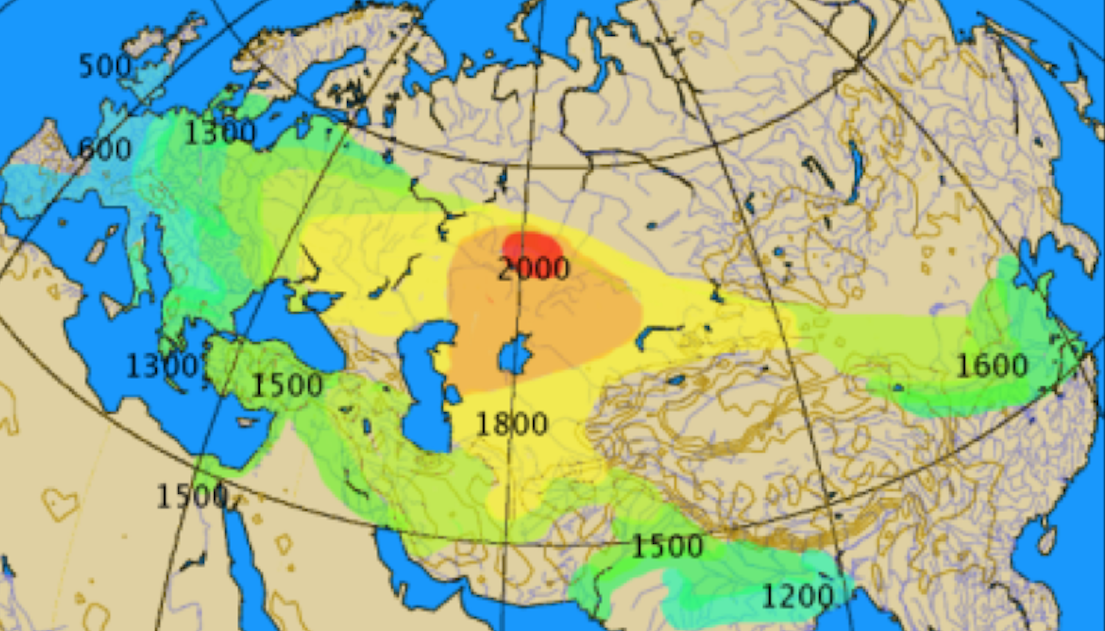

Genghis Khan, a tall, white, red-haired, blue-eyed man, was in many ways the Asian and medieval counterpart of Alexander the Great. His extraordinary personality succeeded in uniting the tribes and clans of Mongolia and in seizing control of the Silk Road, so that by his death in 1227 he was ruler of an empire stretching from the Sea of Japan to the Caspian, ruled from the Mongol capital of Karakorum (not to be confused with the mountain range of the same name). The strongly continental character of these domains was brilliantly portrayed when the Mongol invasion of Japan failed: the steppe horsemen, who had never seen the sea before, suffered severe seasickness and vomiting in their naval adventure, and what the Japanese called kamikaze or ‘divine wind’ caused such heavy losses to the Mongol fleet that the invasion failed. Other environments where Mongolia was never able to make its dominance felt emphatically were the mountains and forests—the Mongols were a people of plains and steppes, and both Siberia and the Russian principalities had huge forest masses. Indeed, at the time of the ‘Mongol yoke’, during which the Russias were tributary to the Tartars, the khanate of the Golden Horde ended where the steppe gave way to the forests of the North. From these closed and impenetrable spaces, Alexander Nevsky, Dmitry Donskoi, Peresvet and other national heroes of Russian history forged the greatness of the future Principality of Muscovy.

The Mongols’ military adventures reached Syria, Poland, Hungary and the gates of Vienna, but they were unable to cross the Sea of Japan or other maritime spaces. You don’t have to be a lynx to appreciate that the Mongol Empire drew its power from the dominance of the Heartland. In the West, the Mongols were able to advance thanks to the excellent information provided at all times by the Venetian merchant intelligence network. One of these agents was Marco Polo’s father.

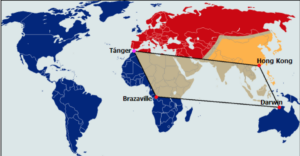

For better or worse, the Mongol conquests provided the Pax Mongolica (or Pax Tatarica) and a relatively stable territorial continuity from the Near East and Eastern Europe to China. Thanks to it, from 1245, on the occasion of the First Council of Lyon, we can find European emissaries sent to the Mongol dominions by order of the Pope and the King of France: Giovanni da Pian del Carpine, Ascelin of Lombardy and André de Longjumeau. The aim was, on the part of the Papacy, to gain influence in Asia, especially by winning over the ancient communities of Nestorian Christians and, on the part of France, to forge links between Louis IX of France and Güyük Khan and to solidify a Franco-Mongol alliance, supposedly to make common cause in the Levant (the time of the Crusades).

In 1253, the Flemish Franciscan monk William of Rubruk was able to cross all of Central Asia and reach Karakorum, where he found French, Russian and Hungarian captured in Hungary. The friar also reported the presence of German prisoners working in iron mines in Central Asia—it seems that Stalin was not the first to capture Germans in Eastern Europe and deport them as slaves to the Heartland. In Mongolia, Islam, Buddhism, Manichaeism and Nestorian Christianity were already flourishing under the religious tolerance of the Khans. Rubruk returned to Europe with a detailed report for King Louis IX of France, entitled Itinerarium fratris Willielmi de Rubruquis de ordine fratrum Minorum, Galli, Anno gratia 1253 ad partes Orientales.

Travels of Friar William of Rubruk. At the time, Sarai played the same role that the Khazarian Sarkel had played before and the Soviet Stalingrad would play later: to serve as a bridge between the Don and Volga rivers, between the Black Sea and Caspian basins—and thus between Europe and the Heartland.

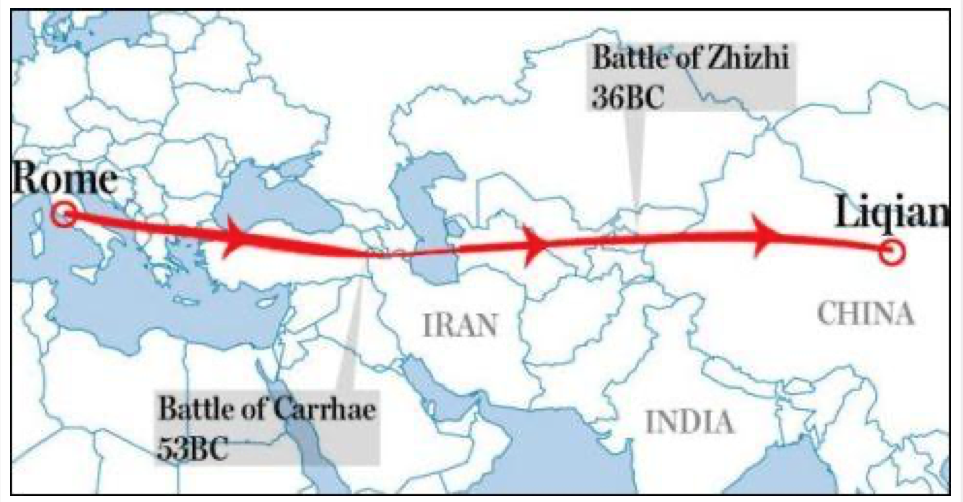

Later in the same century, the brothers Niccolo and Maffeo Polo, Venetian merchants, were able to establish prosperous trading emporiums in Constantinople and in Sudak or Soldaia (see map of the Mongol conquests above), where the presence of the powerful Venetian thalassocracy was strong. Encouraged by the wealth of the Golden Horde khanate, the Polo brothers eventually settled in its capital, Sarai, already within the confines of the Eurasian Heartland. Sarai was located in southern Russia, close to ancient Khazarian Sarkel and modern-day Volgograd, shared with these cities its role as a hinge between the Black Sea and Volga basins (the latter being part of the Heartland) and, with 600,000 inhabitants, was one of the largest and wealthiest cities of the 13th century. There, the Polo brothers became acquainted with the customs of the Tartars, the world of the steppe and the information brought back by foreign traders about distant routes further east. Following these indications, the Venetians proceeded to Bukhara, present-day Uzbekistan, where they lived for three years. They travelled up the Silk Road to Dadu (Beijing), where the throne of Kublai Khan, Genghis’s grandson, was located. The Asian monarch provided them with a Mongol ambassador to the Pope in Rome, safe conduct to travel throughout the Mongol dominions, and a letter to the Pope asking for a sample of oil from the lamp of the Holy Sepulchre, as well as a hundred ‘wise men’ to teach Christianity and Western customs in China. Sino-Roman relations, which had never been able to take shape in antiquity, were beginning to take shape in the middle Ages thanks to Venice, the Papacy and the Mongol conquests.

Pope Gregory X received the missive from the Mongol Khan in 1271, sending only two Dominican friars with the Polo brothers, this time accompanied also by Niccolo’s seventeen-year-old son Marco. The friars did not complete the journey out of fear, while the Venetian merchants completed the Silk Road from one end to the other, arriving in the capital of the Khanate in 1274, three years after their departure. Welcomed by the Khan, they lived under his hospitality for se¬¬venteen years before returning to Europe. The Polo voyages would never have been possible without the existence of a single state from the Middle East to the Pacific; thanks to this, Europe was able to read Marco Polo’s accounts, accessing first-hand testimony about what lay at the heart of Eurasia.

Thanks to the stability of the Pax Mongolica, Marco Polo was not the last European to set foot in Eurasia. In 1318, four years after the dissolution of the Order of the Temple, the Franciscan friar Odorico da Pordenone embarked on an impressive journey that took him from Venice to Armenia, Persia, India, China, Indonesia, and other places in the Far East. He even described Tibet as ‘where the Pope of the idolaters dwells’.

Several events ultimately brought the Pax Mongolica to an end:

• The virulent spread of the Black Death in the 1340s. Originating in Central Asia, the plague spread along both land and sea trade routes, affecting Europe as well as China, India and Arabia and introducing terror, distrust and the quarantining of entire cities along the trade routes.

• The Mongol horsemen were becoming fat, comfortable and decadent, and the Chinese, seasoned in palace intrigue, seized power, driving out the Mongol Yuan dynasty and other foreign (including European and Christian) influences and founding the Ming dynasty in 1368. The coup d’état in China was heavily influenced by a secret society: the White Lotus.

• The fleeting rise of Tamerlane, the last great steppe conqueror, who annihilated the Nestorian Christians of Persia and attacked the khanate of the Golden Horde (southern Russia), causing Muscovy, then ruled by Vasily I, to stop paying tribute to the Tatars. Yet in 1382, Moscow was still sacked by the Tatars.

• Buddhism, a new cultural and ideological trend very different from the ancestral paganism that the Mongols had hitherto professed, had penetrated Mongolia itself. It would take a couple of centuries for Buddhism to gain a foothold in the country. Still, it was only a matter of time before the new monks would win over the local shamans, winning over the Mongol aristocracy and erecting monasteries at crossroads and in the great pasture lands where large numbers of herdsmen gathered to perform sacrifices and other rituals. It has always been rumoured that it was the Chinese who favoured the introduction of Buddhism into Mongolia, hoping that the new creed would defuse the ancient warrior mentality of the Mongols and in turn ease the pressure on the Great Wall fringe; in fact, the White Lotus was a Buddhist society. The process would culminate centuries later, in 1568, when Altan Khan granted the head of the Tibetan lineage, Gelug, the title of ‘Dalai Lama’.

But if the Black Death, Tamerlane’s raids and the collapse of the Khanate had cut off communications between East and West, a new and at first-sight unfortunate event was to restore them: the fall of Constantinople to the Turks in 1453 closed the ‘Varangian route’. It blocked the natural maritime outlet to the steppes, while many Greek immigrants migrated in stages from Constantinople across the Black Sea to Ukraine and eventually Moscow. Europe became an island, surrounded to the west by the Atlantic, to the south by the Mediterranean, to the southeast by the Ottoman Empire and the east by the Golden Horde and other khanates. In this situation, the only states capable of breaking Europe’s insularity and reuniting it with the Greater East by land were the Russian principalities. So the catastrophe of 1453 forced the peoples of Russia to turn eastwards to conquer the Tatar dominions, just as it forced the peoples of the West to turn to the Atlantic to conquer the new world. Both European movements, East and West, initially had a similar goal: to reconnect with Stasia. However, while Europe’s western thrust would accentuate its insularity and maritime character, the eastern thrust would emphasise its terrestrial character.