Note of the Editor:

Those familiar with the critical literature of the New Testament know that there is only one original gospel, that of Mark. Luke and Matthew copied and pasted a bunch of verses from Mark’s gospel to add even more literary fiction from the pen of these two Synoptics (John the Evangelist would later do the same).

Richard Carrier needs no introduction on this site. The new visitor who is unfamiliar with his work can consult the links about Carrier on the sidebar. Precisely because Carrier is a typical left-wing scholar, the exact opposite of post-Nietzscheans like us, I am struck by how he talks about how the evangelist Mark transvalued—the word he uses—the axiology of the Greco-Roman world.

Richard Carrier needs no introduction on this site. The new visitor who is unfamiliar with his work can consult the links about Carrier on the sidebar. Precisely because Carrier is a typical left-wing scholar, the exact opposite of post-Nietzscheans like us, I am struck by how he talks about how the evangelist Mark transvalued—the word he uses—the axiology of the Greco-Roman world.

In his most recent debate, uploaded this morning, with Dennis R. MacDonald, the author of the book he reviews below, Carrier used again the word transvaluation a couple of times right at the beginning of the YouTube debate (just don’t pay attention to the degenerate music that their host chose).

The following is Carrier’s ‘Review of The Homeric Epics and the Gospel of Mark’, a book-review of the MacDonald book, Yale University, 2000 (bold-type added by me):

______ 卐 ______

This is an incredible book that must be read by everyone with an interest in Christianity. MacDonald’s shocking thesis is that the Gospel of Mark is a deliberate and conscious anti-epic, an inversion of the Greek ‘Bible’ of Homer’s Iliad and Odyssey, which in a sense ‘updates’ and Judaizes the outdated heroic values presented by Homer, in the figure of a new hero, Jesus (whose name, of course, means ‘Savior’). When I first heard of this I assumed it would be yet another intriguing but only barely defensible search for parallels, stretching the evidence a little too far-tantalizing, but inconclusive. What I found was exactly the opposite. MacDonald’s case is thorough, and though many of his points are not as conclusive as he makes them out to be, when taken as a cumulative whole the evidence is so abundant and clear it cannot be denied. And being a skeptic to the thick, I would never say this lightly. Several scholars who reviewed or commented on it have said this book will revolutionize the field of Gospel studies and profoundly affect our understanding of the origins of Christianity, and though I had taken this for hype, after reading the book I now echo that very sentiment myself.

This is an incredible book that must be read by everyone with an interest in Christianity. MacDonald’s shocking thesis is that the Gospel of Mark is a deliberate and conscious anti-epic, an inversion of the Greek ‘Bible’ of Homer’s Iliad and Odyssey, which in a sense ‘updates’ and Judaizes the outdated heroic values presented by Homer, in the figure of a new hero, Jesus (whose name, of course, means ‘Savior’). When I first heard of this I assumed it would be yet another intriguing but only barely defensible search for parallels, stretching the evidence a little too far-tantalizing, but inconclusive. What I found was exactly the opposite. MacDonald’s case is thorough, and though many of his points are not as conclusive as he makes them out to be, when taken as a cumulative whole the evidence is so abundant and clear it cannot be denied. And being a skeptic to the thick, I would never say this lightly. Several scholars who reviewed or commented on it have said this book will revolutionize the field of Gospel studies and profoundly affect our understanding of the origins of Christianity, and though I had taken this for hype, after reading the book I now echo that very sentiment myself.

Background and purpose of Mark

MacDonald begins by describing what scholars of antiquity take for granted: anyone who learned to write Greek in the ancient world learned from Homer. Homer was the textbook. Students were taught to imitate Homer, even when writing on other subjects, or to rewrite passages of Homer in prose, using different vocabulary. Thus, we can know for certain that the author of Mark’s Gospel was thoroughly familiar with the works of Homer and well-trained in recasting Homeric verse into new prose tales. The status of Homer in basic education remained throughout antiquity, despite the fact that popular and intellectual sentiment had been sternly against the ethics and theology of his epics since the age of Classical Greece. Authors from Plato (400 b.c.e) to Plutarch (c. 100 c.e.) sought to resolve this problem by ‘reinterpreting’ Homer as allegory, or by expunging or avoiding offensive passages, neither of which was a perfect solution.

For the Latin language, the opportunity was afforded for Virgil to solve this problem by recasting the Homeric epic into Roman form, exhibiting Roman ideals and creating more virtuous heroes and gods. Likewise, borrowing and recasting from Homer is evident in numerous works of fiction, which often had a religious flavour, and were proliferating in the very same period as the Gospels. One prominent example (mentioned but not emphasised by MacDonald) is the Satyricon of Petronius, which can be decisively dated prior to 66 A.D. and thus is most likely earlier than any known Gospel, and since this novel was in Latin (and a satire), it is almost certain that many undatable Greek novels, which surely originated the form, long precede this. So rewriting Homer to depict new religious ideas and values was a standard phenomenon. In MacDonald’s words, ‘Homer was in the air that Mark’s readers breathed’ (p. 8), and all the more so among Mark’s Gentile audience. But to smartly recast Homer into a new Greek form, reflecting contemporary Graeco-Jewish ideals, was a task simply waiting to be done. If MacDonald is right, this is what Mark set out to do. So much is clear: the motive, ability, and inspiration were certainly present, and MacDonald rapidly presents all the evidence, backing it up with copious and scholarly endnotes in chapter 1.

Why? In MacDonald’s words, Mark ‘thoroughly, cleverly, and strategically emulated’ stories in Homer and the Old Testament, merging two great cultural classics, in order ‘to depict Jesus as more compassionate, powerful, noble, and inured to suffering than Odysseus’ (p. 6), and hence ‘the earliest evangelist was not writing a historical biography, as many interpreters suppose, but a novel, a prose anti-epic of sorts’ (p. 7). In particular, the differences between Mark and Homer need no explanation: the differences are the point, the very objective of the later author. Some of those differences are also the obvious result of a change of scene from the ancient Mediterranean to near-contemporary, Roman-occupied Judaea, or of literary borrowing from Jewish texts. Some may reflect some sort of traditional or historical core story, though it is almost impossible to tell when. Instead, it is the similarities that ‘cry out for explanation’, and contemporary apologists must now begin to address this issue.

Of particular use, for all those who want to develop (or attack) theories of literary borrowing—in the Gospels or elsewhere—is the set of six criteria for identifying textual influence outlined by MacDonald at the end of his first chapter, and demonstrated quite effectively on a passage in Acts. Though no one of these criteria alone carries very much weight, the more criteria that are met in a single instance, the stronger the case. However, one caveat MacDonald does not provide is in regard to his criterion of order. In many cases, matching sequences of passages or themes is indeed significant. However, some cases of matching sequence are such that any other sequence would be logically impossible. Therefore, correlation of this kind can in some cases be coincidence. Nevertheless, even engaging this caution, the sequential evidence MacDonald presents is very often, taken as a whole, not coincidental. Likewise, it should be known that much of Mark’s use of Homer is to shape and detail an otherwise non-Homeric story, and the task of deciding what that core story is, or whether this core story in any given case is a Biblical emulation, or a historical fact, or a legend, or something of the author’s deliberate creation, or any combination thereof, is not something MacDonald even intends to undertake in this book, although he makes some suggestions in his concluding paragraphs.

Modeling Odysseus

The Odyssey is rife with the theme of the suffering hero, and MacDonald builds a solid case in chapter 2 for the philosophical veneration of Odysseus as the best example of a man. If Jesus could be made to one-up and even replace Odysseus, Mark would achieve a literary and moral coup. And there are in the overall story obvious if not overly-telling similarities: ‘Both [men] faced supernatural opposition… Each travelled with companions unable to endure the hardships of the journey, and each returned to a home infested with rivals who would attempt to kill him as soon as they recognised him’, and ‘both heroes returned from Hades alive’ (p. 17). Some parallels are a little more startling but less significant to the historian than to the literary critic: the parable of the Wicked Tenants (Mk. 12:1-12), and the passage capturing the famous phrase ‘for you do not know when the master of the house will come’ (Mk. 13:34-5), both evoke the image of Odysseus returning in disguise to surprise the suitors who have turned his house into a den of sin (MacDonald develops this theme further in chapter 5, and again in chapter 14, and in the conclusion). Do not be like them, Mark is saying to his readers. But of course Jesus himself could have said that, intending the very same allusion. Examples like these can make good material for sermons, and serve well the connoisseurs of visionary prose, yet don’t really prove whether Mark has himself deliberately crafted the story. But in conjunction with what follows, this becomes part of a cumulative case for Mark’s inversion of Homer.

Who knew, for instance, that Odysseus was also a carpenter? The companions are another general link with the Odyssey. MacDonald points out how Mark is the harshest evangelist in his treatment of the disciples, while the others sometimes go out of their way to omit or alter this disparagement when they borrow from Mark. Why were the disciples such embarrassing nitwits, ‘greedy, cowardly, potentially treacherous, and above all foolish’ (p. 20)? As history, it is hardly credible. As a play on Homer, it makes perfect sense: for the companions of Odysseus were exactly like this. Homer cleverly employed the ineptitudes of the crew to highlight the virtues of Odysseus, making him appear even more the hero, enhancing his ‘wisdom, courage, and self-control’ (p. 23). MacDonald briefly explores five other general similarities between the two ‘entourages’ in chapter 3, including the fact that in the one story we have sailors, while in the other, fishermen-who do a lot of going about in boats, even though the vast majority of Judaea is dry land.

Chief among these similarities is the comparison between Peter and Eurylochus. Both spoke on behalf of all the followers, both challenged the ‘doomsday predictions’ of their master to their own peril, both were accused by their leader of being under the influence of an evil demon, and both ‘broke their vows to the hero in the face of suffering’—in effect, both ‘represent[ed] the craven attitude toward life’ (p. 22-3). Again, this could be a mere veneer woven through an otherwise true story by Mark, and some of MacDonald’s ideas (such as developed in chapter 4) are intriguing but too weak to do much with. But it is true that both epics announce from the start a focus on a single individual, both center on a king and his son reestablishing authority over a kingdom, both involve an inordinate amount of events and travel at sea. Both works begin by summoning their own Muse: Homer, the Muse herself; Mark, the Prophet Isaiah. In both stories, the son’s patrimony is confirmed by a god in the form of a bird, and this confirmation prepares the hero to face an enemy in the very next scene: Telemachus, the suitors; Jesus, Satan. And eventually the odd links keep accumulating, and compel one to question the whole thing.

Stark examples

‘Once the evangelist linked the sufferings of Jesus to those of Odysseus, he found in the epic a reservoir of landscapes, characterisations, type-scenes, and plot devices useful for crafting his narrative’ (p. 19). Of course, all throughout MacDonald points out coinciding parallels with the Old Testament and other Jewish literature, but even these parallels have been moulded according to a Homeric model in every case he examines. Consider two of the many mysteries MacDonald’s theory explains, and these are even among the weakest parallels that he identifies in the book:

Why do the chief priests need Judas to identify Jesus in order to arrest him? This makes absolutely no sense, since many of their number had debated him in person, and his face, after a triumphal entry and a violent tirade in the temple square, could hardly have been more public. But MacDonald’s theory that Judas is a type of Melanthius solves this puzzle: Melanthius is the servant who betrays Odysseus and even fetches arms for the suitors to fight Odysseus—just as Judas brings armed guards to arrest Jesus—and since none of the suitors knew Odysseus, it required Melanthius to finally identify him. MacDonald also develops several points of comparison between the suitors and the Jewish authorities. Thus, this theme of ‘recognition’ stayed in the story even at the cost of self-contradiction. Of note is the fact that Homer names Melanthius with a literary point in mind: for his name means ‘The Black One’, whereas Mark seems to be maligning the Jews by associating Melanthius with Judas, whose name is simply ‘Judah’, i.e. the kingdom of the Jews, after which the Jews as a people, and the region of Judaea, were named.

Why does Pilate agree to free a prisoner as if it were a tradition to do so? Such a practice could hardly have been approved by Rome, since any popular rebel leader who happened to be in custody during the festival would always escape justice. And given Pilate’s reputation for callous ruthlessness and disregard for Jewish interests, it is most implausible to have him participating in such a self-defeating tradition—a tradition for which there is no other evidence of any kind, not even a precedent or similar practice elsewhere. But if Barabbas is understood as the type of Irus, Odysseus’ panhandling competitor in the hall of the suitors, the story makes sense as a clever fiction. Both Irus and Barabbas were scoundrels, both were competing with the story’s hero for the attention of the enemy (the suitors in one case, the Jews in the other), and both are symbolic of the enemy’s culpability.

Of course, Barabbas means ‘son of the father’ and thus is an obvious pun on Christ himself. He also represents the violent revolutionary, as opposed to the very different kind of saviour in Jesus (the real ‘Saviour’). On the other hand, Irus was a nickname derived from a goddess (Iris), and MacDonald fails to point out that her name means ‘rainbow’, which to Mark would have meant the sign from God that there would never again be a flood (Ge. 9:12-13). Moreover, Irus’ real name was Arnaeus, ‘the Lamb’. What more perfect model for Mark? The Jews thus choose the wrong ‘son of the father’ who represents the Old Covenant (symbolised by the rainbow, and represented by the ideal of the military messiah freeing Israel), as well as the scapegoat (the lamb) sent off, bearing the people’s sins into the wilderness, while its twin is sacrificed (Lev. 16:8-10, 23:27-32, Heb. 8-9). MacDonald’s own analysis is actually confirmed by this additional parallel that he missed, and that is impressive.

MacDonald goes on to develop many similar points that not only scream of Homer being on Mark’s mind, but also explain strange features of Mark. The list is surprisingly long:

Why did Jesus, who nevertheless taught openly and performed miracles everywhere, try to keep everything a secret? Why did Jesus stay asleep in a boat during a deadly storm? Why did Jesus drown two thousand pigs? Why does Mark invent a false story about John the Baptist’s execution, one that implicates women? Why are the disciples surprised that Jesus can multiply food even when they had already seen him do it before? Why does Jesus curse a fig tree for not bearing fruit out of season? How does Mark know what Jesus said when he was alone at Gethsemane? What is the meaning of the mysterious naked boy at Jesus’ arrest? Why does Jesus, knowing full well God’s plan, still ask why God forsook him on the cross? Why does Mark never once mention Mary Magdalene, or the other two women at the crucifixion, or even Joseph of Arimathea, until after Jesus has died? Why is the temple veil specifically torn ‘top to bottom’ at Jesus’ death? Why is Joseph of Arimathea able to procure the body of a convict so soon from Pilate? Why do we never hear of Joseph of Arimathea again? Why does Jesus die so quickly? Why do the women go to anoint Jesus after he is buried? Why do they go at dawn, rather than the previous night when the Sabbath had already ended?

All these mysteries are explained by the same, single thesis. This is a sign of a good theory. With one theoretical concept, not only countless parallels are identified, but numerous oddities are explained. That is very unlikely to be due to chance. And there is evidence of so many plausible connections, that even though any one of them could perhaps with effort be argued away, the fact that there are so many more makes it increasingly unlikely that MacDonald is seeing an illusion. Finally, his entire theory is plausible within the context of what we can deduce to have been Mark’s cultural and educational background.

Crescendo of doom

MacDonald’s book is built like a crescendo: as one reads on, the cases not only accumulate, they actually get better and better, clearer and clearer. In the story of the Gerasene swine (Mk. 5:1ff) MacDonald finds that 18 verses have thematic parallels in the Odyssey, 13 of those in exactly the same order! And even with some of those out of order the order is not random but is inverted, and thus a connection remains evident. In the story of Salome and the execution of John, MacDonald finds seven thematic parallels with the Murder of Agamemnon, all of them in the same order, and on top of that he details two other general parallels. And the two food miracles, forming a doublet in Mark, contain details that match a similar doublet of feasts in the Odyssey, and contain them in the same respective order: ‘Details in the [first] story of Nestor’s feast not found in the [second] story of Menelaus appear in the [first] feeding of the five thousand and not in its twin’ while ‘details in the [second] story of Menelaus not found in the [first] story of Nestor appear in the [second] feeding of the four thousand and not in the first story’ so that ‘the chances of these correspondences deriving from accident are slim’ (p. 85).

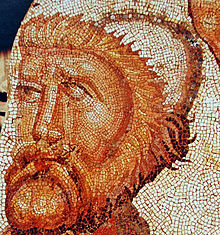

(Editor’s interpolated note: A mosaic depicting Odysseus, from the villa of La Olmeda, Pedrosa de la Vega, Spain, late 4th-5th centuries c.e. Both he and Homer are always depicted as whites.)

(Editor’s interpolated note: A mosaic depicting Odysseus, from the villa of La Olmeda, Pedrosa de la Vega, Spain, late 4th-5th centuries c.e. Both he and Homer are always depicted as whites.)

These examples of a connection between Mark and Homer are far denser than the two examples I detailed earlier, and cannot be explained away even by the most agile of thinkers. Consider the last case, which even has the fewest parallels relative to the other two: in the first feasts, the main characters go by sea, but in the second, by land; in the first, only men attend (even though there is no explanation in Mark of why this should be), but in the second there is no distinction; in the first, the masses assemble into smaller groups, and lie on soft spots, but not in the second; more attend the first than the second (and the numbers are about the same: 5000 in Mark, 4500 in Homer).

On the other hand, in the second feasts, unlike the first, someone asks the host a discouraging question and yet the host shows compassion anyway—in Mark, this is particularly strange, since after the first miracle the disciples have no excuse to be surprised that Jesus can multiply food, so the doubting question can only be explained by the Homeric parallel; finally, in the second feasts, as opposed to the first, there are two sequential courses—bread, then meat. In both authors, the feasts serve an overt educational role: in the one case to educate the hero’s son about hospitality, in the other to educate the disciples about Jesus’ power and compassion, drawing attention to the difference in each story’s moral values. There are even linguistic parallels—Homer’s feasts were called ‘symposia’ (drinking parties) even though that word usually referred to smaller gatherings; likewise, Mark writes that the first feast was organised by ‘symposia’, despite the fact that only food is mentioned, not water or wine. Several of these details in Mark, as noted, are simply odd by themselves, yet make perfect sense when we see the Homeric model, and therein again lies the power of MacDonald’s thesis.

MacDonald does similar work illuminating the Transfiguration, the healing of Bartimaeus, the Hydropatesis (water-walk), the Marcan Apocalypse, the Triumphal Entry, the Anointing, the Passover Feast (including a definite connection with cannibalism that offers a possible ideological origin for the Eucharist as a transvaluation of Homer), the Prayer and Arrest at Gethsemane, the Crucifixion, the Burial, and some details of the Empty Tomb narrative. His theory provides an excellent reason to suppose that the naked boy at Jesus’ arrest is the same as the boy the women find in the empty tomb—and he is a marker of resurrection: a type of the ill-fated Elpenor. Likewise, his theory puts a serious damper on the historicity of Joseph of Arimathea and the burial account in Mark: Joseph is a type of Priam, who rescued the body of Hector for burial in a similar way.

What I found additionally worthwhile is how MacDonald’s theory illuminates the theme of ‘reversal of expectation’ which so thoroughly characterises the Gospels—not only in the parables of Jesus, where the theme is obvious, but in the very story itself. Though MacDonald himself does not pursue this in any detail, his book helped me to see it even more clearly. James and John, who ask to sit at the right and left of Jesus in his glory, are replaced by the two thieves at Jesus’ crucifixion: Simon Peter, Jesus’ right-hand man who was told he had to ‘deny himself and take up his cross and follow’ (8:34), is replaced by Simon of Cyrene when it comes time to truly bear the cross; Jesus is anointed for burial before he dies; and when the women go to anoint him after his death, their expectations are reversed in finding his body missing.

Later Gospels added even more of these reversals: for instance in Matthew Jesus’ father, Joseph, is replaced by Joseph of Arimathea when the duty of burial arose—a duty that should have been fulfilled by the father; likewise, contrary to expectation, the Mary who laments his death and visits his tomb is not Mary his mother, but a prostitute; and while the Jews attack Jesus for healing and doing good on the Sabbath, they in turn hold an illegal meeting, set an illegal guard, and plot evil on the Sabbath, and then break the ninth commandment the next day. This theme occurs far too often to have been in every case historical, and its didactic meaning is made clear in the very parables of reversal told by Jesus himself, as well as, for instance, his teachings about family, or hypocrisy, and so on. These stories were crafted to show that what Jesus preached applied to the real world, real events, ‘the word made flesh’.

Death and resurrection

MacDonald’s book concludes with an analysis of how Jesus as a character in Mark is also an inversion of Hector and Achilles in the Iliad. Both Jesus and Achilles knew they were fated to die and spoke of this fate often, but whereas Achilles chose his fate in exchange for ‘eternal fame’, and for himself alone, Jesus chose it in exchange for ‘eternal life’, for all humankind. This is one among many examples of how Mark has updated the values in Homer, highlighting this fact by crafting his narrative in deliberate imitation of Homer’s epics. In a similar fashion, while the death of Hector doomed Troy to destruction, Jesus’ death doomed the Temple to destruction. According to MacDonald, these themes and others guide Mark’s construction of the passion narrative, and though borrowing from the Old Testament and other Jewish texts in the passion account is far more prevalent than anywhere else in his Gospel, there is still a play on the Iliad evident in various details.

For example, MacDonald finds more than 11 parallels between Mark’s account of the crucifixion and the death of Hector, all but one of those in the same order (and that one exception is in inverted order), and 11 more parallels between Mark’s account of the burial of Jesus and Homer’s account of the burial of Hector, all in the same order. It is notable that resurrection, anastasia, was a theme in the Iliad: the concept appears three times, twice in declarations of its impossibility, once in a metaphor for Hector’s survival of certain death. It thus contained a fitting challenge that Mark was happy to answer with a simple prose epic that everywhere flaunted the fact that anastasia was indeed possible, and real. While Hector, Elpenor, and Patroclus were all burned and buried at dawn, the tomb of Jesus was empty at dawn; while the Iliad and Odyssey were epics about mortality, the Gospel was an epic about immortality.

The ending of Mark

I have one point of criticism for chapter 21, where MacDonald diverges from his central thesis to explain why Mark ends his Gospel as he does. MacDonald proposes an explanation from the historical context of the author. It is quite likely that many Christians were killed, and the original Jerusalem church destroyed, in the Jewish War of 66-70 A.D. MacDonald in several places relates how Mark most likely wrote his Gospel after the conclusion of the war (there are, to be sure, ample references that assume this, as well as that the world would end soon thereafter—cf. especially MacDonald’s third appendix). So Mark, MacDonald argues, was faced with explaining why Jesus had not forewarned his disciples to evacuate Judaea. Mark’s explanation, so the theory goes, is that Jesus did warn them, but they never heard the warning—in particular, they were supposed to go to Galilee after the resurrection to see Jesus, but the women failed to report this to the disciples and so they never went (and this tactic also allows the disciples to get off the hook: those at fault were mere fickle women).

The problem with this theory should be obvious: it is not the fact that it fails to explain how Mark could know the story if no one told it—for this did not stop him from relating what Jesus said in private when no witnesses were at hand, nor did it stop Matthew from relating secret conversations of the Jews; rather, the problem is that it fails to explain how Christianity started. Even assuming Mark is inventing this account apologetically, how did Mark imagine that the resurrection ever began to be preached if no one was ever told about the empty tomb and no one saw the risen Jesus, even in visions or dreams? Since the earliest accounts, in Paul, clearly suggest post mortem sightings of Jesus, and even tie these to the origin of the Gospel itself (and I have in mind the revelation to Paul mentioned in Galatians, and the visions to Peter and the others mentioned in 1 Corinthians), it does not seem plausible for Mark to expect his readers to reject this tradition, as would be required for his alleged hidden point even to be noticed, much less understood. I thus cannot buy MacDonald’s theory on this point.

(Editor’s interpolated note: An icon of Saint Mark the Evangelist, 1657. Note that he’s depicted as swarthy.)

(Editor’s interpolated note: An icon of Saint Mark the Evangelist, 1657. Note that he’s depicted as swarthy.)

My own hypothesis is that Mark ended the Gospel thus in order to set up a pretext for why little of his particular story had been heard in the Christian community until he wrote it down. If we suppose that the resurrection as preached by Paul was of a spiritual nature, and therefore had nothing to do with empty tombs, then to suddenly disseminate such a story would raise eyebrows unless the author were ready with an explanation. And by building an explanation into his story he essentially covers himself. It is possible that Mark originally concluded his tale with an assertion that the women later reported the story to him, an ending that would be struck out and replaced to suit the new physicalist Christology that would follow, as well as in support of the new reliance on apostolic authority which seems never to have been a concern for Mark.

But it is also possible that this would not have mattered. The faithful would not necessarily be too bothered about Mark’s sources, since Revelation itself could always provide (in his letter to the Galatians, Paul himself claimed he learned the Gospel through direct revelation from God). Even if they were to ask, Mark or the sellers of his story could easily have provided persuasive oral explanations to satisfy any believer, who would be more than ready to believe anything that agreed with their values and doctrine and glorified and magnified the power of their beloved Lord. Ultimately, if Mark invented the empty tomb, he may also have inadvertently caused the invention of a physical resurrection—since an empty tomb, though meant as a symbol, if taken as a fact could imply a physical resurrection, leaving room for future evangelists to spin the yarn further still.

Conclusion

What is especially impressive is the vast quantity of cases of direct and indirect borrowing from Homer that can be found in Mark. One or two would be interesting, several would be significant. But we are presented with countless examples, and this is as cumulative as a case can get.

In the end, I came away from this book with a new appreciation for Mark, whose Gospel tends to be derided as the work of a rather poor, simple Greek author. Though Mark’s Greek is extremely colloquial, not at all in high literary style, this itself is surely a grand and ingenious transvaluation of Homer: whereas the great epics were archaic and difficult, only to be mastered by the educated elites, only to be understood completely by those with access to glossaries and commentaries and marked-up critical editions, Mark not only updated Homer’s values and theology, but inverted its entire character as an elite masterpiece, by making his own epic simple, thoroughly understandable by the common, the poor, the masses, and lacking in the overt pretension and cleverness of poetic verse, written in plain, ordinary language. The scope of genius evident in Mark’s reconstruction of Homeric motifs is undeniable and has convinced me that Mark was no simpleton: he was a literary master, whose achievement is all the greater in his choice of idiom-his ‘poor Greek’ was deliberate and artful, as was his story.

Another theme that becomes apparent throughout this book is how quickly Christians lost touch with this allegorical meaning. Even the other Evangelists, when borrowing from Mark, stripped out the key and telling details and thus obviously missed the point; and only one other author, that of the Acts of Andrew, did anything overtly comparable in comprehensively recrafting Homer. By itself, this might be evidence against such a meaning actually being in Mark. But the evidence that this meaning is present is overwhelming on its own terms, and we can only conclude of early Christian ignorance, instead, that the real origins and message of the earliest Christians was all but lost even to the second or third generation. By the time there was a church in a significant sense, Christianity had been radically changed by the throngs of its converts, and, amidst the din of outsiders who stole the reigns, the very essence of that original Church of Jerusalem faded, powerless to survive under the mass of superstition and arrogance.

Having read this book, I am now certain that the historicity of the Gospels and Acts is almost impossible to establish. The didactic objectives and methods of the authors have so clouded the truth with literary motifs and allusions and parabolic tales that we cannot know what is fact and what fiction. I do not believe that this entails that Jesus was a myth, however—and MacDonald himself is not a mythicist, but assumes that something of a historical Jesus lies behind the fictions of Mark. Although MacDonald’s book could be used to contribute to a mythicist’s case, everything this book proves about Mark is still compatible with there having been a real man, a teacher, even a real ‘miracle worker’ in a subjective sense, or a real event that inspired belief in some kind of resurrection, and so on, which was then suitably dressed up in allegory and symbol.

However, the inevitable conclusion is that we have all but lost this history forever. The Gospels can no longer support a rational belief in anything they allege to have occurred, at least not without external, unbiased corroboration, which we do not have for any of the essential, much less supernatural details of the story. And if Alvar Ellegård is right (Jesus: One Hundred Years Before Christ, Overlook, 1999), Mark was almost entirely fiction, written after the sack of Jerusalem to freeze in symbolic prose the metaphorical message of Christianity, a faith which began with a Jesus executed long before the Roman conquest, who then appeared in visions (like that which converted Paul) a century later, in the time of Pilate, to inspire the new creed.

What is important is not that this can be decisively proven—nothing can, as our information is too thin, too scarce, too unreliable to decisively prove anything about the origins of Christianity. What is important is that theories like Ellegård’s can’t be disproven, either—it is one among many distinctly possible accounts of what really happened at the dawn of Christianity, which MacDonald’s book now makes even more plausible. And so long as it remains possible, even plausible, that the bulk of Mark is fiction, the contrary belief that it is fact can never be secure.